by Julie McConnell | Jul 1, 2014

Panhandle residents have seen caterpillars in abundance this June. One common visitor to pecan trees is the Walnut Caterpillar Datana integerrima. The walnut caterpillar has a very narrow host range and feeds only on trees in the Juglandaceae family which includes walnut, pecan, and hickory trees. They are sometimes seen on other plant material, but feeding on non-host plants is unlikely.

Walnut caterpillar feed on the leaves of host trees through several growth stages and molts until they have reached the final larval instar and are ready to pupate into an adult moth. Their color changes from light green when newly hatched to reddish-brown to almost black with long white hairs as they mature. The caterpillars group together in large masses and may hang from each other and dangle from the tree branches when molting. Instead of creating a cocoon in the tree, the walnut caterpillar moves to the ground beneath the tree and burrows into the soil or leaf litter to pupate and emerges later as a moth.

What can you do if your pecan tree is hosting walnut caterpillars?

Although the numbers seen on trees may be alarming, a healthy tree can tolerate some feeding damage. Stripped branches may increases the chance of a lower yield of fruit because the removal of leaves does reduce the amount of energy the tree can produce, but overall health of the tree should not be significantly affected. However, many homeowners find falling caterpillars and their excrement unappealing and may decide to take steps to manage the population.

There are several natural enemies that feed on caterpillars, so avoid using a broad spectrum insecticide that might harm predatory insects and other animals. Consider using a biological control product such as Bt (Bacillus thuringiensis) that is only lethal to caterpillars. Other methods are “pick and squish” or drowning in a bucket of soapy water. Next year, in the spring, watch for masses of tiny green eggs on the underside of leaves and remove and destroy them before hatching.

For more information visit USDA Forest Service Forest Insect & Disease Leaflet 41 “Walnut Caterpillar”

by Alex Bolques | Jun 17, 2014

Homeowner accounts of white fluffy woolly masses on woody ornamentals have been on the rise. They can appear on the ends of a wide variety of woody ornamental branches in the landscape. A closer inspection of these white woolly masses can provide the curious observer with a startling surprise. “It’s Alive!” It moves and seems to jump at you, most likely jumping away from you. Once you have recovered from the mildly frightful encounter, you ask yourself, “What was that?”

Adult citrus flatid planthopper, Metcalfa pruinosa

(Say). Credits: Photograph by: Lyle J. Buss, University of Florida

They are planthoppers (Metcalfa pruinosa), an insect in the order Hemiptera. The common name for this woolly looking planthopper is the citrus flatid planthopper (CFP). As the name implies, they occur on citrus but can also be found on many woody ornamentals and fruit trees. The adult planthopper wing arrangement is tent-like, meaning that the forewings are held over the insect abdomen in a tent configuration.

Nymph of the citrus flatid planthopper, Metcalfa

pruinosa (Say). Credits: Photograph by: Lyle J. Buss,

University of Florida

The nymph, young immature insect, produces the white woolly material that is characteristic of CFP. At first sight, they can be mistaken for mealy bugs, which may look similar since they are covered with cottony white filaments. They can also be mistaken for cottony cushion scale.

Mealybugs. Credits: James Castner, University

of Florida

Cottony cushion scales, Icerya purchasi, on twig.

Credits: James Castner, University of Florida

In both of these cases of mistaken identities, the insect will not jump or hop around. No chemical control is necessary although sooty mold can occur on heavily populated plants. In that case, a soapy water treatment can be applied.

Follow these links to more information on the citrus flatid planthopper, mealy bugs, and cottony-cushion scale.

by Larry Williams | Jun 3, 2014

Glistening webbing formed by tree cattle (psocids) Photo credit: Doug Caldwell, University of Florida

Many people are noticing small insects on trunks and branches of their trees. When disturbed, these insects move in a group and are commonly called tree cattle because of this herding habit. They are ¼ inch brownish-black insects with white markings.

Some people assume that these insects will injure their trees but they are harmless. They could be considered beneficial.

These insects are called psocids (pronounced so-cids). They have numerous common names including tree cattle and bark lice. They feed on lichen, moss, algae, fungi, spores, pollen and the remains of other insects found on the tree’s bark. As a result, they are sometimes referred to as bark cleaners.

Tree cattle may form webbing. This webbing is tight against the tree’s trunk and/or limbs. It appears suddenly. The webbing is used as a protection from weather and predators. Underneath you may find psocids.

The glistening webbing may attract a person’s attention resulting in the tree being visually inspected from top to bottom. A dead branch or other imperfections in the tree may be noticed and then wrongly blamed on the tree cattle. I’ve talked to homeowners that sprayed their trees with insecticides or that hired pest control businesses to treat the trees as a result of finding the webbing/psocids. One person told me that he cut down a tree after finding tree cattle. He wrongly assumed that these insects were pests that might move through the area and kill trees. He thought he was doing a good thing.

Adult female psocids lay eggs in clusters on leaves, branches and tree trunks. After hatching, the immature insects (nymphs) remain together under their silk webbing. Adults have wings which are held roof-like over their body. Nymphs are wingless. Psocids usually have several generations per year in Florida.

After seeing the webbing and/or insects, many people insist on spraying insecticides because they believe these insec

Under the webbing live hundreds of psocids. Photo credit: UF/IFAS Jim Castner

ts are damaging their trees. But as mentioned, they are bark cleaners and do not damage trees. If the silk webbing is considered unsightly, a heavy stream of water from a garden hose can be used to wash insects and webbing off infested trees. If nothing is done, the webbing usually goes away in several weeks.

Psocids can be found on many rough-barked hardwood trees and palms. Occasionally, they may be found on wood siding, fence posts or similar areas.

by Eddie Powell | Jun 3, 2014

During this growing season monitor your plants and keep them healthy as a healthy plant will be able to better survive an invader attack.

Nematode populations can be reduced temporarily by soil solarization. It is a technique that uses the sun’s heat to kill the soil-borne pests. Adding organic matter to the soil will help reduce nematode populations as well. Nematodes are microscopic worms that attack vegetable roots and reduce growth and yield. The organic matter will also improve water holding capacity and increase nutrient content.

Tomato Spotted Wilt Virus

Credits: UF/IFAS

If you choose to use pesticides, please follow pesticide label directions carefully. Learn to properly identify garden pests and use chemicals only when a serious pest problem exists. If you have questions please call your UF/IFAS county extension office. We can provide helpful information about insect identification.

Organic gardeners can use certain products like BT(Dipel) to control pests. Please remember not every off-the-shelf pesticide can be used on every crop. So be sure the vegetable you want to treat is on the label before purchasing the product.

Follow label directions for measuring, mixing and pay attention to any pre-harvest interval warning. That is the time that must elapse between application of the pesticide and harvest. For example, broccoli sprayed with carbaryl (Sevin) should not be harvested for two weeks.

Spray the plant thoroughly, covering both the upper and lower leaf surfaces. Do not apply pesticides on windy days. Follow all safety precautions on the label, keep others and pets out of the area until sprays have dried. Apply insecticides late in the afternoon or in the early evening when bees and other pollinators are less active. Products like malathion, carbaryl and pyrethroids are especially harmful to bees.

To reduce spray burn, make sure the plants are not under moisture stress. Water if necessary and let leaves dry before spraying. Avoid using soaps and oils when the weather is very hot, because this can cause leaf burn.

Control slugs with products containing iron phosphate.

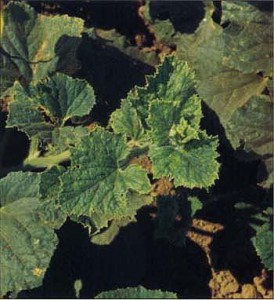

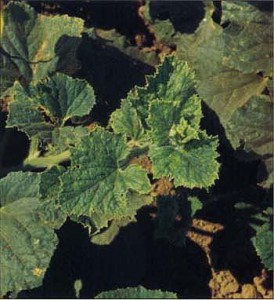

Cucumber Mosaic Virus

Credits: UF/IFAS

Many common diseases can be controlled with sprays like chlorothalonil, maneb, or mancozeb fungicide. Powdery mildews can be controlled with triadimefon, myclobutanil, sulfur, or horticultural oils. Rust can be controlled with sulfur, propiconazole, ortebuconazole. Sprays are generally more effective than dusts.

by Julie McConnell | May 27, 2014

Lady bird beetle and aphids. Photo: Julie McConnell, UF/IFAS

The most numerous animals on the planet are insects and although less than 1% cause damage to our landscapes, most are viewed as pests. Many insects perform clean up tasks that keep our environment from being littered with carcasses and trash while others actually attack and feed upon insects that are direct pests to plants.

It is important to recognize that all insects are not pests and take the time to get to know a few that might actually be performing a beneficial job in your landscape. Probably the most easily recognized beneficial bug family in Florida landscapes are the ladybird beetles (Coccinellidae). There are several species of ladybird beetles with different food preferences including mildews, mites, whiteflies, scale insects, and aphids.

Another group of insects that include some predatory species is the stink bugs. Some stink bugs do eat plants, but there are also many that are beneficial such as Florida predatory stink bug (Euthyrhynchus floridanus). The Florida predatory stink bug preys on velvetbean caterpillar, okra caterpillar, alfalfa weevil, and flatid planthopper. One of the distinguishable characteristics between plant feeding and insect feeding stinkbugs are the shape of their shoulders. Plant feeders have rounded shoulders and predatory have points on their shoulders.

The next time you are disturbed by a bug in your garden, take a moment to watch what it is eating and try to identify it before assuming it is a pest. After all, there are many beneficial bugs that help to balance out the “bad bugs.”

by Beth Bolles | May 27, 2014

Frass (toothpick-like projections) extends from entry holes on a Jeruselum thorn damaged by cold temperatures. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF IFAS Escambia Extension

Winter injury and stress to many trees has attracted granulate ambrosia beetles to landscapes. These beetles mostly prefer weakened trees and cut stumps/logs but have been found to attack some healthy trees as well.

Adult beetles are very small, only about 1/16 inch long and bore into branches and trunks of many woody plants. They will push out small ‘strings’ of boring dust which look like toothpicks. These strings successfully protect the beetles as they establish galleries for laying eggs and rearing young within the tree. The adult females will introduce a fungus (ambrosia) into these galleries on which both the young beetles and adults feed.

Ambrosia Beetle Entry Point. Photo by Matthew Orwat

Many beetles will bore into a plant, mostly along the trunks. Plants may be ultimately killed, not by the beetles but by the fungi that interfere with the movement of fluids within the tree.

If you notice a tree infested with ambrosia beetles, it is best to remove the plant quickly. Remove all infested plant parts from your landscape. If you have a special plant that you want to save, you may be able to cut it back close to the ground, and allow it to resprout. It would be necessary to monitor the remaining portion carefully for reinfestation and treat with an approved insecticide to prevent beetle entry.

Interior of damaged stem.