by Daniel J. Leonard | Dec 4, 2025

My previous article outlined the benefits of planting trees during the winter dormant season. Once planted, it’s then time to implement one of the best practices that helps ensure successful establishment of recently installed trees and shrubs – mulching.

Mulching, by definition, is simply the process of adding a layer of material over the top of the soil. Like planting at the right time, mulching does many great things for your landscape. Mulching helps moderate temperatures; the soil stays warmer in the winter and cooler in the summer. Mulching increases water retention; when the sun isn’t blasting directly onto the soil, it dries out much more slowly. Mulching reduces weed pressure; most weed seeds require sunlight to germinate. Etc. Etc. The benefits of mulch abound. But what material you use and how you apply mulch figure heavily into whether your mulch helps or harms the plants whose roots it lies over.

Pine bark mulch applied correctly in a landscape. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

There are two basic options when considering mulch: organic or inorganic sources. In general, you should always select an organic mulch that is derived from local sources. Organic mulches are mulches derived from natural materials like pine straw, leaves, tree bark, or shredded wood chips. These mulches break down over time and benefit soil health through bettering water holding capacity, increasing soil porosity and organic matter content, and drastically expanding the soil biome (beneficial worms, fungus, and bacteria that live in the soil). Organic mulches also allow landscapes to blend in with the natural areas surrounding homesites as they typically use materials found in local ecosystems. For example, in the coastal south, pine forests dominate, pine straw is plentiful, and purchasing usually supports local businesses that grow, harvest, and market the straw. So, unless you happen to live in a desert environment where rocks are natural, steer clear of rocks or other inorganic mulches.

Pinestraw mulch applied around a newly planted tree. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

As with most things, there is a Goldilocks zone for mulch. Too little isn’t enough to keep weeds from easily poking through and soil from quickly drying. Too much and you risk depriving plant roots from oxygen exchange with air above, trapping too much moisture and causing rot issues, or even creating a hydrophobic layer of dried mulch that repels rainfall and irrigation. Instead, just the right amount of mulch should be applied, enough to create a 2-3” layer of helpful mulch. With some mulches like straw, this may mean applying a 6-8” layer that will settle down to the magic 2-3” number with a good rain, interlocking the individual pieces of straw. With others like wood chips or bark nuggets, there will be little settling, and the applied amount should be 2-3” deep. A final tip is to always pull mulch back a little from the crowns of plants and the trunks of woody trees and shrubs to prevent potential disease issues.

So, after you install your new landscape plants this winter, remember to mulch well. Be sure to select an organic mulch that supports local industries, enhances the soil in your landscapes, protects your plants’ roots, prevents weeds, and looks natural! For more information about mulch or any other horticultural topic, contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension Office. Happy Gardening!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Nov 26, 2025

With cold temperatures having arrived in the Panhandle last week, we’re finally getting close to prime landscape planting season. But why is winter the best time to install landscape trees and shrubs? Shouldn’t we plant when things are leafed out and growing? While it’s counterintuitive to think bitter cold, dreary days are significantly better to plant landscape plants in than the warm, sunny days of summer, it’s usually true! Let’s explore why winter is the time to plant woody trees and shrubs and then look at some of the best woody plants no Panhandle landscape should be without.

Most people from elsewhere think that Florida is always lush, green, and tropical. Those people have clearly never been to the Panhandle – heck it snowed last year! Our region of Florida has more in common, climate wise, with the rest of the south – subtropical with long hot, humid summers and wet, mild winters (though rain has been hard to come by recently), occasionally wracked by intense cold fronts. Because of those cold fronts, tropical plants cannot survive, and woody plants enter a dormant stage where above ground growth ceases. This cold-forced dormant season is the perfect time to plant woody plants because the planting process is stressful (the root system is purposefully damaged to remove circling and J-shaped roots and encourage outward growth) and regular rainfall and cool temps means conditions are right for plants to get a solid root system re-established before growth and transpiration begins in the heat of spring/summer.

Now that you know why we plant woody landscape plants when we do, let’s select a few quintessential, versatile Florida-Friendly trees and shrubs (2 each, one native and one non-native) to install in our landscapes this planting season.

Nuttall Oak (Quercus texana) is one of the most adaptable landscape trees around. The species is tolerant of many soil types, native to moist bottomland areas but tolerating drier spots well once established. While it’s a large tree – up to 70-80’ tall, I find its rounded upright habit to often be more in scale with landscapes than the wide spreading Live Oak (Quercus virginiana). Nuttall Oak certainly has many positive attributes (tough, wind-resistant, pollinator friendly, etc), but its fall color is probably my favorite. For the Panhandle it is quite good, delivering autumnal hues of red and orange.

It’s not North Carolina Sugar Maple color but Nuttall Oak possesses attractive foliage. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Crape Myrtle (Lagerstroemia indica) is the most widely grown landscape tree in the South for good reason! They’re tough, widely adapted, offer excellent summertime flower displays, and possess interesting architecture and unique bark. The primary consideration with Crape Myrtle is simply picking the right one. Do you need an upright, compact tree? Choose ‘Sioux’ or ‘Apalachee’. Do you want a big crape that can double as a small shade tree? Choose ‘Natchez’ or ‘Muskogee’. Do you want a new dwarf variety or one with black foliage? There’s now plenty of those to choose from as well. There’s truly a Crape Myrtle for every yard.

Oakleaf Hydrangea (Hydrangea quercifolia) is a wonderful native flowering deciduous shrub that’s at home in all Panhandle landscapes. It prefers moist soil with a little afternoon shade but can tolerate most conditions thrown at it. Growing 5-7’ in height, sporting footlong white flower panicles each summer, and beautiful foliage each fall, Oakleaf Hydrangea is a must. You can find unnamed seedlings of the species or look for named varieties such as ‘Snow Queen’, ‘Semmes Beauty’, and ‘Alice’. In my experience, you can’t go wrong with any of them.

Camellia Sasanqua is without a doubt my favorite fall flowering shrub. Impossibly durable (it’s common to find specimens over 100 years old), incredibly beautiful in flower and form, and coming in all shapes, sizes, and flower color, a Sasanqua of some kind belongs in ever yard. A few of my favorites are ‘Leslie Ann’ (upright form, white/pink bicolored flowers), ‘Shi Shi Gashira’ (dwarf that makes an excellent informal hedge), and ‘Yuletide’ (compact plant with red flowers & showy gold stamens).

So, as the weather continues to be mild with those cold front swings occasionally and rain begins to be more regular, think about getting some woody trees and shrubs planted into your landscape this winter. Keep in mind the excellent above selections and be sure to check out the Florida-Friendly Landscaping Plant Guide for more possibilities! Happy Gardening!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Jun 5, 2025

The Panhandle’s dreaded summer heat has finally arrived in force and has brought with it one of the most difficult to control lawn/landscape weeds, our annual enemy Doveweed (Murdannia nudiflora). Doveweed is characterized as one of the world’s worst weeds due to its broad range of growing conditions, ability to root along its stems, forming mats as it grows, massive seed production (each plant can produce up to 2,000 seeds per year), and inconspicuous nature – it looks like a grass to the untrained eye. So, what can gardeners do to control Doveweed that’s already up this year and prevent it next summer? Let’s find out.

Doveweed emerging in a bare patch of a Centipedegrass lawn in late May 2025. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

First, the best prevention for all weeds, Doveweed included, is a healthy lawn/landscape. Ensuring healthy, thick Centipedegrass turf and landscaped beds that don’t allow light to hit bare soil goes a long way towards reducing the overall weed load lawns and landscapes can experience. For lawns, this can be achieved through mowing regularly at the proper height for your turfgrass (2.5” or so for Centipedegrass), irrigating no more than 0.75”-1” per week in the absence of rain, limiting stress from overfertilization, and removing excess thatch. In landscapes, preventative weed control focuses on limiting overwatering/fertilization and maintaining a 2-3” organic mulch layer of pinestraw, pine bark, leaves, wood chips, etc. Adopting these practices can greatly reduce the occurrence of weeds in your yard, however they will not eliminate weeds altogether and supplemental chemical weed control is often necessary.

Unlike Crabgrass, Florida Pusley, and other commonly encountered Panhandle annual weeds that emerge when the soil begins to warm in early spring (usually late February-March), Doveweed waits until mid-April-May (soil temperatures of 70-80 degrees F). All these annual weeds are best controlled by preemergent herbicides, like Indaziflam (Specticle G), before seeds germinate. For Doveweed, that means the first preemergent application should occur mid-April with a follow-up application 6-8 weeks later. However, for this year that opportunity is behind us and our only option is post emergent herbicides.

Which postemergent herbicide you choose depends on if your Doveweed issue is in turfgrass or in landscaped beds. In landscaped beds, the primary control option is either hand pulling or spot treating Doveweed with a 41% glyphosate product (Roundup and other generic products) at a rate of 3% (3-4oz glyphosate/gal). As glyphosate is a non-selective herbicide, be sure to not get any overspray on any ornamental plant foliage. In turfgrass, Doveweed control becomes a little more difficult. You essentially have three options – atrazine, a generic 3-way broadleaf product, or a commercial grade broadleaf product. Though it provides very good control of Doveweed and has pre-emergent properties to help discourage future weeds, I don’t prefer atrazine because it has a high potential to leach into groundwater following heavy rains in sandy soils, which describes much of the Panhandle. The generic 3-way products (usually a mix of Dicamba, Mecoprop, and 2,4-D) are fairly effective on Doveweed, however follow-up applications are usually required and the 2-4D component can be harsh on Centipedegrass at the higher label rates required for Doveweed control. Though somewhat expensive, the best post emergent option for most people is probably a commercial grade product like Celsius WG. Celsius WG is a very strong post emergent broadleaf herbicide that is very effective on Doveweed and is also very safe on Centipedegrass, even in hot weather. If the cost of the product (>$100) is off-putting, it is helpful to remember that even at the highest labelled rate, a 10 oz Celsius WG bottle goes a long way, enough to cover several acres of lawn.

* Regardless of what method you choose, be sure to get after emerged Doveweed seedlings early, before they mature and begin flowering – even the strongest post emergent herbicides work better on young weeds.

While Doveweed is a nasty little plant that is perfectly capable of taking over a lawn or landscaped bed, there are a variety of preventative and control options available. Using a combination of the above techniques should help achieve lasting Doveweed controls in future seasons! For more information about Doveweed and other summer annual weed control in lawns and landscapes, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension County office.

by Carrie Stevenson | Dec 18, 2024

A large Carolina wolfberry shrub thrives near St. Marks’ lighthouse at the wildlife refuge. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

I was lucky enough to spend a weekend in November exploring a lovely, low-key stretch of northwest Florida. We hiked trails and took the boat tour at Wakulla Springs State Park, marveling at the numerous alligators and admiring birds and a slow-moving manatee. We also hiked through St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, which is home to a nearly 200-year-old lighthouse and keeper’s house, which have a fascinating history of their own.

The brilliant red, and edible, berry of the Carolina wolfberry is ripe in late fall/early December. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Exploring the shoreline of Apalachee Bay behind the lighthouse, we watched fiddler crabs run the salt flats and herons quietly stalk their prey. Always on the lookout for something new, I noticed a large shrub growing several yards back from the beach. It looked like a cross between a rosemary and a holly, with delicate lavender/purple flowers and brilliant red teardrop-shaped fruit. I’d never seen it before.

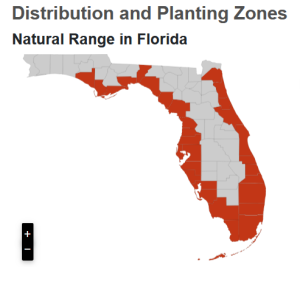

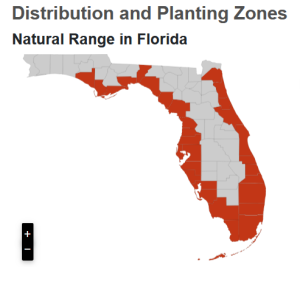

Map of the natural range of Carolina wolfberry in Florida. Figure courtesy of the Florida Native Plant Society.

After a quick investigation, I learned it was a Carolina wolfberry, aka Carolina deserthorn, aka Christmas berry (Lycium carolinianum). The invasive species coral ardisia (Ardisia crenata) is also known in some areas as Christmas berry—this is why scientific names are so useful—but that is not the plant we saw at St. Marks. The native Carolina wolfberry was located right where you might expect it, on dry coastal scrub, in view of the saltwater it easily tolerates. Its native range in Florida starts along the coastline east of here, particularly Bay and Wakulla counties and all the way down around the state.

The delicate lavender flower of the Carolina wolfberry is a popular nectar source for native butterflies. Photo credit: Peggy Romfh

The tall shrub is evergreen, with leaves adapted into a long, thin, slightly succulent near-needle shape. This leaf form helps hold water in a dry, salty environment and prevents evaporation. The tips of the shrub’s branches have thorns, hence the common name “desert-thorn.” Carolina wolfberry produces those attractive little purple blooms in the fall, providing nectar for several species of native butterflies. In late fall/early winter, the brilliant red fruits show up. They are less than an inch long and reminiscent of peppers. When ripe, the fruit are edible and are described as sweet and tomato-like. The fruit are not only popular for human consumption, but also for birds, deer, and raccoons. Just before we walked down the beach, another visitor saw a bobcat disappear into the shrub, which provides cover for many additional species besides those who eat it directly.

Illustration from a 15th century plant medicine book showing the mandrake, a member of the Solanaceae family.

Carolina wolfberry is a member of the Solanaceae family, aka nightshade (sometimes referred to as “deadly nightshade”). Other relatives include edible tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, eggplant, and groundcherry. The “deadly” part refers to related species like belladonna and mandrake, from which toxic poisons can be extracted. If you’re looking for a fascinating historical deep dive into these plants’ connection to witches, Shakespeare, and the death of multiple Roman emperors, look no further than the US Forest Service’s web page on the “Powerful Solanaceae” family!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Nov 13, 2024

One of my favorite landscape plants is blooming right now in Panhandle landscapes – ‘Soft Caress’ Mahonia. ‘Soft Caress’ was first introduced into the commercial nursery trade in 2006 and included in the Southern Living Plant Collection, but didn’t achieve garden fame until 2013 when it won first place in the Royal Horticultural Society’s (RHS) prestigious Chelsea Flower Show. I first planted a group of ‘Soft Caress’ about ten years ago and as those plants have matured, so too has my appreciation for them. The following are a couple of my favorite outstanding aspects of these small shrubs.

Fall Flowers. Other than camellias, there isn’t a lot else in Panhandle landscapes blooming from mid-November to January and ‘Soft Caress’ Mahonia helps fill that flower void. Brilliant yellow flower spikes rise above the deep-green fernlike foliage and very welcome in this otherwise drab and dreary gardening season.

‘Soft Caress’ Mahonia’s winter flowers are excellent pollinator attractors. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

Quick growing but small statured. If you’ve gardened very long, you’ll know this is a tough ask! Plants that reach mature size relatively rapidly but also don’t get very big are a rare breed. ‘Soft Caress’ Mahonia grows quickly but also maxes out in size rather quickly – mine are very easily maintained at 3-4’ in height with a single annual trim.

~10-year old ‘Soft Caress’ Mahonia Shrub. Photo courtesy Daniel Leonard.

Extremely tough and adaptable. My Mahonia plants have persisted through drought, hurricanes, floods, and freezes and have never looked better. These little plants are simply tough. They’ve had no disease issues and no pest problems (except for a little deer browsing one year, but that appears to be an isolated incident). While they prefer shade, they can also handle several hours of morning sun without incident.

‘Soft Caress’ Mahonia is a standout plant that fills a mostly flowerless period in landscapes, fills its designated landscape spot quickly but won’t outgrow it, and is truly tough. Add a couple to your landscape this winter!

by Julie McConnell | Oct 31, 2024

A recent visit to the Dothan Area Botanical Garden (DABG) reminded me that although many of our summer flowers are winding down, we have a great garden show coming this winter when the southern classic camellias start to show their stuff. DABG has a large collection of camellias that will start blooming in the coming months. Here is a little background on the two most common types of camellias grown in our area.

A recent visit to the Dothan Area Botanical Garden (DABG) reminded me that although many of our summer flowers are winding down, we have a great garden show coming this winter when the southern classic camellias start to show their stuff. DABG has a large collection of camellias that will start blooming in the coming months. Here is a little background on the two most common types of camellias grown in our area.

Camellia japonica

Also known as Japanese Camellia, C. japonica thrive in partial sun to full shade. Direct morning sun with some shelter from the sun in the hottest part of the day is a good compromise. Too much shade can reduce flowering, so aim for at least partial sun.

Most Japanese Camellias bloom from January to March, but some may start earlier in the season. Flower shapes include single, semi-double, anemone, peony, and formal double. Flower colors are white, pink, red, and sometimes a combination of multiple colors! Camellia japonica mature at 10-15’ tall and wide but may get as big as 25 feet. This makes them ideal to create privacy in the garden or have the lower limbs trimmed into a tree-form.

Camellia sasanqua

Sasanqua camellias also prefer part sun but can also thrive in full sun once established. Leaves and flowers are typically smaller than C. japonica which is an easy way to differentiate. Although most have upright habits and can grow 10-15’ tall as well, there are a few cultivars such as ‘Shishi Gashira’, ‘Bonanza’, and ‘Mine-no-yuki’ that have more horizontal branching making them good options for foundation plantings. Sasanqua camellia are usually in full bloom in the fall, but may bloom as late as January. Flower shapes are similar to C. japonicas, but many varieties have more open flowers with exposed stamens that are beneficial to pollinators.