by Daniel J. Leonard | Jan 10, 2018

Are you guilty of “Crape Murder”, the dreaded horticultural sin that involves lopping off your beautiful Crape Myrtles fence post high and creating gnarly looking knuckles? No need to raise hands, you know who you are! Despite the cruelness of this act, all is not lost; there is still time to repent and change your ways! The facts of the matter are, if you have made a habit of lopping the tops off your crapes, you are most definitely not alone, you probably thought you were doing the right thing, and it can be corrected.

Improper pruning of crape myrtles. Photo Courtesy – Beth Bolles.

Crape Myrtle (Lagerstroemia spp.) are one of the most beautiful trees Southerners have in their horticultural arsenal. Unsurpassed in both form and flower, it is easy to see why Crape Myrtle is the most widely planted tree in the Southeastern United States. A mature Crape Myrtle properly grown is a remarkable sight, sinewy limbs reaching high in a vase shape supporting lilac-like flowers that come in a rainbow of colors. These qualities make it even more strange that homeowners and landscape professionals alike insist on butchering them every winter.

Before we move on to corrective procedures, let us examine a few of the reasons that crape murder is committed. First, I think peer pressure has a lot to do with it. When one sees every house on the street and all the business landscapes doing things a certain way, one tends to think that is the correct way. Second, there are folks who believe that pruning their crapes back each year creates a superior flower show. In reality, this practice creates an overabundance of succulent, weak, whippy branches (with admittedly larger flowers) that tend to bend over and break after a summer wind or rainstorm and are more prone to pests and disease. In addition, many homeowners over prune their crapes in this way because they planted a cultivar that grows too large for the site. There are dozens of crape myrtle cultivars sold, be mindful to pick one with a mature size and shape that will fit with the scale of the site!

So, now that we know why crape murder is committed, let’s discuss how to remedy it once the atrocity has already occurred.

- If the improper pruning has not been going on very long (a couple of years or less), it may be possible to correct over time without taking drastic measures. If this is the case, select two or three of the young “whippy” canes that are growing up and out and remove the rest. Ideally, the canes you select will be growing away from the center of the plant and not back into the middle of the plant or straight up to facilitate proper branch spacing as the tree continues to grow. The canes you select now will become primary branches in the years to come, so plan and prune carefully. Repeat for each main trunk that has been “murdered”. You will have to keep watch on the cut areas, as they will attempt to regrow as suckers after pruning; simply remove these juvenile shoots until they stop emerging.

Properly pruned crape myrtle. Photo courtesy – North Carolina Cooperative Extension

- If the murder has been going on for more than a year or two, it likely cannot be corrected without a major rejuvenation of the plant. Though it will likely be painful for you emotionally and seemingly run counterintuitive to your instincts, the best method to rejuvenate a disfigured crape is to break out the chainsaw and cut the plant back to the ground! This forces the plant to do one of two things; either grow an outrageous number of new shoots or die. In most cases however, the crape myrtle’s tough constitution permits it to regrow from the stump. The first growing season after performing this procedure, allow the shoots that sprout to grow and do not prune. The winter following the first growing season, remove all except three to five strong, well-spaced shoots and allow these to become the new plant’s main trunks. In all succeeding years, only prune to remove dead wood, crossing branches and branches growing toward the center of the plant.

If you have been guilty of crape murder, it is not too late to change your ways! Follow these steps, get out and enjoy the cool weather, and get to correcting your mistakes while the plants are still dormant! As always, if you have any questions about the topic of this article or any other horticultural topics, please contact your local Extension office and happy gardening!

by Sheila Dunning | Dec 14, 2017

Photo by Sydney Park Brown UF/IFAS

Photo by Sydney Park Brown UF/IFAS

Holly has been considered sacred in some cultures because it remained green and strong with brightly colored red berries no matter how harsh the winter, even when most other plants would wilt and die. According to Druid lore, hanging the plant in homes would bring good luck and protection.

Later, Christians adopted the holly tradition from Druid practices and developed symbolism to reflect Christian beliefs. Today, the red berries are said to represent the blood that Jesus shed on the cross when he was crucified. Additionally, the pointed leaves of the holly symbolize the crown of thorns Jesus wore on his head.

Several holly species are native to Florida. Many more are cultivated varieties commonly used as landscape plants. Hollies (Ilex spp.) are generally low maintenance plants that come in a diversity of sizes, forms and textures, ranging from large trees to dwarf shrubs.

The berries provide a valuable winter food source for migratory birds; however, the berries only form on female plants. Hollies are dioecious plants, with male and female flowers on separate plants. Both male and female hollies produce small white blooms in the spring. Bees are the primary pollinators, carrying pollen from the male hollies 1.5 to 2 miles, so it is not necessary to have a male plant in the same landscape.

Several male hollies are grown for their compact formal shape and interesting new foliage color. Dwarf Yaupon Hollies (Ilex vomitoria ‘Shillings’ and ‘Bordeaux’) form symmetrical spheres without extensive pruning. ‘Bordeaux’ Yaupon has maroon-colored new growth. Neither cultivar has berries.

Hollies prefer to grow in partial shade but will do well in full sun if provided adequate irrigation. Most species prefer well-drained, slightly acidic soils. However, Dahoon holly (Ilex cassine) and Gallberry (Ilex glabra) naturally occur in wetland areas and can be planted on wetter sites.

For a more comprehensive list of holly varieties and their individual growth habits refer to ENH42 Hollies at a Glance: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/mg021

by Daniel J. Leonard | Aug 11, 2017

Growing in containers can be one of the most versatile ways to add color, texture and mobility to the landscape. However, gardeners generally reach for finicky annuals to fill their pots with pizzazz. The problem with this strategy is that most annuals and perennials need to be watered constantly, fertilized regularly, and changed out with the seasons. That sounds like a little bang for a whole lot of buck! I and most of the real plant people I know fall squarely in the school of lazy gardening and believe there is an easier, less intensive, and ultimately less expensive way to get the same result. This can be accomplished by thinking outside the box and using an alternative class of plants that can fit the same bill of providing color and texture in pots without the headaches and have been sitting on the shelves right in front of us the whole time, the shrubs.

It is beyond me why shrubs aren’t used as container plants more often. Maybe the reason for the lack of use is pure perception; after all, no one with any sense would plant a giant, coarse green meatball or an enormous antebellum azalea in a decorative pot on their front walk. Recent innovations by plant breeders have left this argument moot though as new introductions of old species have revived interest in the entire group. Many of the best of these new cultivars sport traits perfect for container culture (dwarf growth habit, increased flowering, and interesting texture and form) while preserving the ironclad, undemanding nature of their parent plants. The following are a few of my favorite new shrub introductions for container growing!

- ‘Purple Pixie’ Loropetalum

Purple Pixie loropetalum is a low-growing shrub that can spill beautifully out of a container. (Photo by MSU Extension Service/Gary Bachman)

If interesting architecture is what you require in a plant, ‘Purple Pixie’ must be on display in your yard. This dwarf cultivar of the wildly overused purple shrub Loropetalum chinense has taken the horticultural world by storm. The unique combination of true purplish foliage that only greens slightly in the hottest summer sun, ribbon-like pink spring flowers, and a graceful weeping habit make ‘Purple Pixie’ a winner. Give this plant a medium sized container (at least 12” in diameter), water when the soil begins to dry, fertilize infrequently with a slow-release formulation, site in full sun to partial shade, and enjoy for many seasons to come.

This is definitely not your granddaddy’s Ligustrum. Gone are the rampant growth, sickly sweet smelling flowers, and the aggressive nature of ‘Sunshine’s’ parent Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense). ‘Sunshine’ is a sterile cultivar with dwarf characteristics (growing 4-5’ with infrequent light pruning), vivid yellow-chartreuse foliage, and most importantly, no flowers. All ‘Sunshine’ asks of us is plenty of sun, occasional fertilizer and a light haircut once or twice a season! Use this plant to frame a dark flowerbed or in a container as a companion to the previous plant, ‘Purple Pixie’ Loropetalum for an extremely striking combination!

‘Sunshine’ Ligustrum. Photo courtesy of JC Raulston Arboretum.

A new take on a landscape standard, ‘Baby Gem’ is an exceptionally compact and slow growing cultivar of Buxus microphylla var japonica. All the same features gardeners love about traditional “full-size” boxwoods remains (tight, formal growth habit, ability to prune into many different shapes and ironclad constitution) but with ‘Baby Gem’ are delivered in a perfect package for a pot. This little “gem” of a plant is perfect for use in a smallish container to frame a formal landscape or to give a sense of order to an informal container garden or border!

So if you’re ready to stop replacing all of your potted plants each and every season, reach for one of these shrubs the next time you are at a garden center. You’ll likely be rewarded with compliments on your creativity, four season interest from the plants themselves, and more time to enjoy being in your garden instead of laboring in it! As always, if you have any questions about this or any other horticultural topics please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office! Happy Gardening!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Apr 24, 2017

Almost every landscape has a problem area where the sun just doesn’t shine and many plants won’t make it, maybe it’s the north side of your house, under a small tree, or tucked away in an oddly-shaped alcove. We all know the same old boring green choices that work well here (Holly Fern, Cast Iron Plant, etc.) but maybe you want something a little bit different, something that will provide a pop of color and interesting texture! Look no further than a recent introduction, a whole-plant mutation discovered from the little-used Grape Holly (Mahonia spp.), aptly named ‘Soft Caress’.

‘Soft Caress’ Mahonia is a beautiful little evergreen shrub from the Southern Living Plant Collection (one of the best of the collection in my opinion) and really is a game changer for full-shade areas. Some of you may remember the traditional Mahonia, also known as Grape Holly, from your grandmother’s lawn. Those plants were coarse, spiny, produced messy purplish berries and often appeared generally unkempt. ‘Soft Caress’ is a major departure from its parent. Possessing finely-cut, deep green, bamboo-like foliage, this plant’s texture really contrasts well with many traditional shady species. As a bonus, ‘Soft Caress’ sends up brilliant yellow-gold flower spikes in the dead of winter, certainly a welcome respite from the other barren plants in the landscape; although in this unusually warm year, the plants are just now blooming in the Panhandle.

Photo courtesy: Daniel J. Leonard

‘Soft Caress’ is advertised to grow three feet in height and width, a more manageable size than the larger traditional Mahonia species, but I’m not sure I’d take that as gospel, the three-year old plants (hardly mature specimens) in my parent’s landscape are already that size and show no signs of slowing down. However, I’ve found you can easily manage their size with a once a year prune to slow down some of the more rapidly-growing canes. Be sure to time the prune as soon as possible after flowering is finished as ‘Soft Caress’ blooms only once a year and produces its flowers on the previous season’s wood, just like Indica Azaleas and old-fashioned Hydrangeas.

The uses in the landscape for ‘Soft Caress’ Mahonia are nearly endless. It pairs well with almost anything in a shady mixed shrub border. It works nicely as a foundation plant against a porch or under windows on the north or east side of a house where it will be protected from hot afternoon sun; I have employed a grouping of the plants in this way in my own lawn with success. It even thrives in containers! If you want to show off some serious horticultural design skills, mix ‘Soft Caress’ in a large container on the porch with some like-minded perennials for a low-maintenance, high-impact display that you don’t have to replant each season. All this shrub requires is partial to full shade, moist well-drained soil, and an occasional haircut to keep it looking tidy! If you’ve been struggling to find a plant that’s a little more unusual than the standard garden center fare and actually looks good in shady spots, you could do a lot worse than ‘Soft Caress’ Mahonia.

As always, happy gardening and contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension office for more information about this plant and other gardening questions!

by Beth Bolles | Mar 30, 2017

We often talk about sandy, nutrient poor soil in Florida and how difficult it is for growing many favorite landscape plants. Gardeners may spend considerable time and money amending soils with organic matter to improve quality.

The low maintenance approach is to embrace your sandy soil and consider plants that thrive in sandy, well-drained soil. One very attractive native shrub that actually prefers this type of soil is false rosemary, Conrandina canescens.

False rosemary is a member of the mint family that is well adapted to drier, sandy soils. It can be found in many coastal communities growing in natural areas. It is easily recognized in the spring and early summer by light purple blooms. Considered a small shrub or groundcover, False rosemary needs full sun. One plant can easily spread out to 4-5 feet in diameter with a height of 2-3 feet.

False rosemary is an attractive native plant for Gulf Coast landscapes. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF Escambia County Extension

False rosemary does have aromatic foliage and is attractive to bees. It is a very low maintenance plant once established and its few issues tend to be related to soils with too much moisture and plants being shaded after establishment. New seedlings will emerge around the main plant when growing conditions are right. If you want to try this native plant in your landscape, talk to a local nursery.

False rosemary flowers are attractive to pollinators. Photo by Beth Bolles, UF Escambia County Extension

by Mark Tancig | Mar 29, 2017

As an extension agent, I’m always curious of what plants folks are using in the landscape. One plant I’ve been noticing more and more of in north Florida, both in containers and in landscape beds, is asparagus fern. Three different plant species go by the name asparagus fern – Sprenger’s fern (Asparagus aethiopicus), foxtail fern (Apsaragus densiflorus), and lace fern (Asparagus setaceus). Property owners should refrain from selecting these plants since they are another example of invasive, exotic species that can spread to natural areas and effect native plant communities.

Native to South Africa, Asparagus species are technically not a fern, but related to lilies, and, yes, asparagus. Its ease of growth has made them a go-to choice for gardeners looking for a hardy, attractive plant. Unfortunately, the red berries that follow the small, white, scented flowers are fed on and spread by birds. The seeds germinate easily and can become established in other parts of the garden or, even worse, a local natural area. The ability of Sprenger’s fern to spread into and disrupt natural ecosystems has earned it a spot on the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council’s List of Invasive Species as a Category I invasive plant. Category I plants are reserved for those plants that have been documented as causing ecological harm to Florida’s ecosystems. Foxtail fern and lace fern should also be used with caution.

Asparagus fern in a storefront planter. Photo Credit: Mark Tancig.

Birds can carry the red berries near and far. Photo Credit: Mark Tancig.

To remove asparagus fern from the landscape, manual or mechanical removal can be effective for small areas. Be careful to dig up all roots. For larger areas, the use of a dilute glyphosate herbicide product will provide control. Retreatment may be necessary.

If you’re looking for other alternatives to asparagus fern, try these Florida-Friendly alternatives: Coastal sunflower (Helianthus debilis), coontie (Zamia pumila), Coleus (Plectranthus scutellarioides), or Cast Iron plant (Aspidistra elatior).

Coastal sunflower. Photo Credit: UF/IFAS.

Coontie. Photo Credit: UF/IFAS.

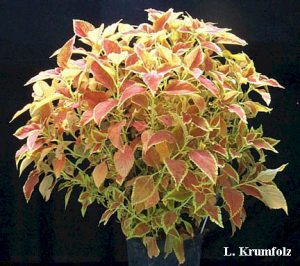

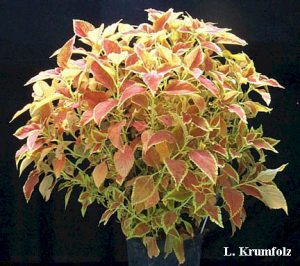

Coleus. Photo Credit: UF/IFAS.

Cast iron plant. Photo Credit: Julie McConnell.

Photo by Sydney Park Brown UF/IFAS

Photo by Sydney Park Brown UF/IFAS