by Alex Bolques | Feb 4, 2014

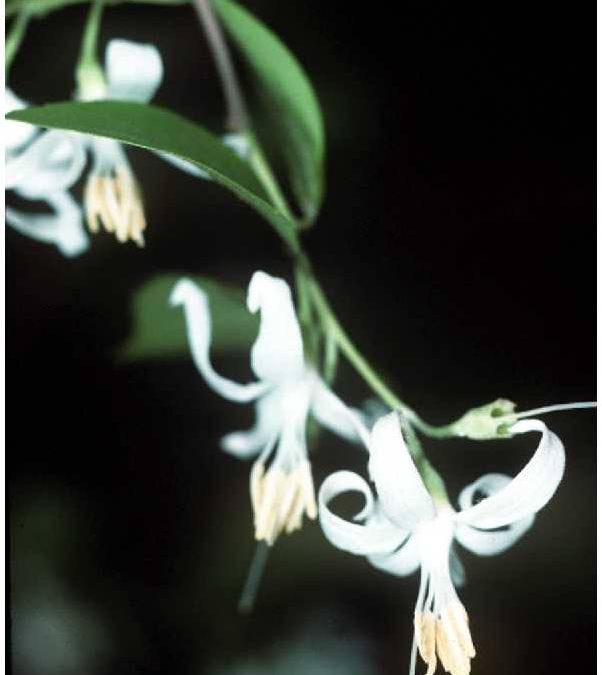

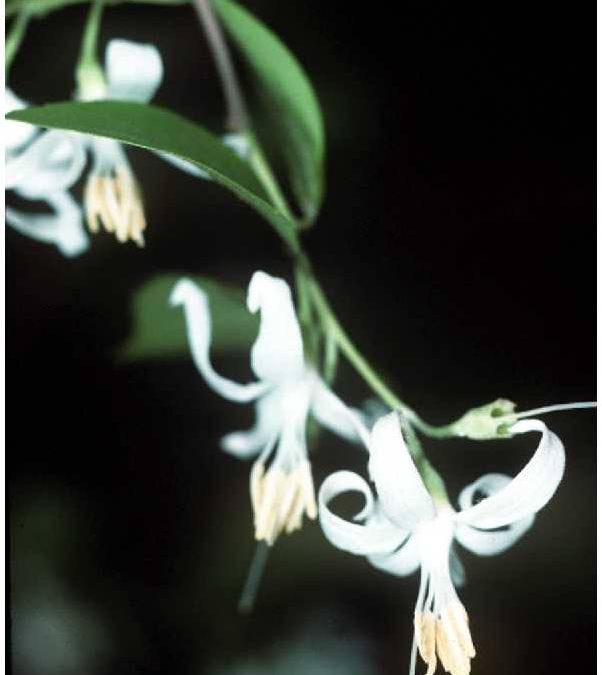

Robert H. Mohlenbrock @ USDA-NRCS PLANTS Database / USDA SCS. 1991. Southern wetland flora: Field office guide to plant species. South National Technical Center, Fort Worth.

Found throughout the North Florida Panhandle, the American snowbell, Styrax americanus, is a native small flowering tree. In his book, The Trees of Florida, Gil Nelson describes the blossoms as charming with “the thin, reflexed (flower) petals curve back over the flower base, leaving an attractive mass of yellowish stamens protruding from the star-shaped corolla”. It has dark green deciduous foliage, with the tree reaching up to 16 feet in height. The attractive blooms appear April – July.

Considered as an understory tree, American snowbell grows best in wet partially shaded areas and is somewhat tolerant of full sun. It prefers wet places such as swamps, wet woods, edges of cypress ponds and moist to wet, cool, acid sandy to sandy loam soils. Wet areas of the home landscape where water puddles occur provide adequate growing conditions for the American snowbell.

Wildlife benefits include nectar for bees and butterflies and edible fruit for birds. To try American snowbell in the landscape, check with local native plant nursery or search online. Note: other Styrax species can be found online that are non-native.

Other source: The Native Plant Database

by Beth Bolles | Jan 14, 2014

Trees and shrubs often serve a distinct purpose in landscapes, other than to provide color. They are planted to provide shade, screen a view or noise, or to soften the hardscapes of the home.

With a little planning, we can have both beauty and function from trees and shrubs. Add a few trees and shrubs that have color in different seasons and your landscape will always be interesting.

The added benefit of growing trees and shrubs is that they are low maintenance. Once the plants are established in the landscape, they will require very little water and only an occasional application of a slow release fertilizer. A good layer of an organic mulch around the plants will help conserve moisture, prevent weeds, and keep root temperatures regulated during our temperature extremes. You may have to do a little pruning every year to remove any diseased, damaged, or severely crossing branches.

Here is a list of plants to give you garden interest throughout all seasons:

Winter color

- Taiwan cherry (Prunus campanulata) is an underutilized ornamental cherry for the coastal south. Clusters of dark pink flowers cover the plant which grows about 20 feet.

Taiwan cherry

- Camellia japonica is widely used in landscapes, but still an excellent choice for winter color. Careful selection of types will provide a garden with color from November through April.

- Red maple (Acer rubrum) will provide color in both the late winter and fall. Flowers are brilliant red in late winter and leaves begin turning red in late October.

- Other choices include Oakleaf hydrangea, Florida anise, Red buckeye, and Japanese magnolia

Spring

- Fringe tree (Chionanthus virginicus) can be in shrub or tree form and range in height from 10 – 20 feet. Forms white clusters of showy fringe-like flowers in late winter and early spring before the leaves emerge.

Fringe tree

- Chinese fringe (Lorepetalum chinesis ‘Rubrum’) is a very popular shrub. Pink blooms are heaviest in the spring. The plants can get up to 12 feet in height so plant it were it will not obstruct a view.

- Virginia sweetspire (Itea virginica) forms clusters of white flowers. Plants offer purplish foliage in the fall.

- Other choices include Banana shrub, native azaleas, Indian hawthorn, and Deutizia,

Summer

- Chaste tree (Vitex agnus castus) is a large shrub with fragrant leaves and spikes of purple flowers. Tolerates drought and develops interesting shape.

Chaste tree

- Loblolly bay (Gordonia lasianthus) is an evergreen tree that grows to 25-35 ft in height. Large white flowers with yellow stamens resemble camellia blooms.

- Abelia spp has white flowers that appear over the entire plant. It is attractive to butterflies .

- Other choices include Crape myrtle, Althea, Confederate rose, and Oleander

Fall

- Bald cypress (Taxodium distichum) will become a large tree over time. In the fall the feathery leaves will turn orange-brown. Good tree for both wet and dry areas.

- Beautyberry (Callicarpa americana) a native that forms clusters of purple berries that line the stem. Leaves turn yellow and provide fall interest as well.

- Cassia bicapsularis can reach 8-12 ft in height and will have bright yellow flowers that form in October and persist until a freeze.

Cassia

by Gary Knox | Jan 7, 2014

‘Apalachee’ has light lavender flowers. Photo by Gary Knox

‘Apalachee’ crapemyrtle is a statuesque small deciduous tree with lavender flowers, dark green leaves and cinnamon-orange bark. Lagerstroemia indica x fauriei ‘Apalachee’ is one of the hybrids released in 1987 from the breeding program of the U.S. National Arboretum. It grows as an upright to vase-shaped, multi-stemmed tree in USDA Cold Hardiness Zones 7a-9b.

Seed capsules of ‘Apalachee’ add winter interest. Photo by Gary Gnox

Seed capsules add unexpected winter ornament to the leafless branches of the deciduous tree. Because individual flowers are packed tightly in the flower panicle, the seed capsules are correspondingly closely spaced. Persisting seed capsules add interest to the tree’s profile similar to the way dried flowers of oakleaf hydrangea continue to add interest long after the flowers have faded.

Crapemyrtle grows and flowers best in full sun with rich, moist soil but is tolerant of drought and all but wet soils. ‘Apalachee’ has good resistance to powdery mildew, very good resistance to cercospora leaf spot and moderate resistance to flea beetle (Altica sp.). This hybrid is susceptible to crapemyrtle aphid. ‘Apalachee’ performs best with minimal pruning. Crapemyrtle is best located away from pavement and structures that may be stained by fallen flowers.

Cinnamon-orange bark of ‘Apalachee’. Photo by Gary Knox

‘Apalachee’ grew to a height of 26 feet and a width of 21 feet in 15 years at former University of Florida facilities in Monticello, Florida. It was one of the most outstanding crapemyrtles in that evaluation planting. This crapemyrtles’ form, vigorous growth, dark green leaves, lavender flowers, cinnamon-orange bark, and persistent seed capsules give it year-round appeal and allow it to stand out among crapemyrtle cultivars.

Lagerstroemia indica x fauriei ‘Apalachee’ has not yet been evaluated using the IFAS Assessment of Non-Native Plants in Florida’s Natural Areas. Without this assessment, the temporary conclusion is that Lagerstroemia indica x fauriei ‘Apalachee’ is not a problem species at this time and may be recommended.

‘Apalachee’ crapemyrtle in full bloom. Photo by Gary Knox

by Mary Salinas | Dec 24, 2013

East Bay Holly. Photo by Mary Derrick, UF IFAS

[important]The best time to plant a tree was 20 years ago. The next best time is now. ~Chinese Proverb[/important]

In Florida, Arbor Day is always celebrated on the third Friday of January. In 2014, Arbor Day falls on Friday, January 17.

Consider planting a tree to enhance your property. Trees provide many benefits such as:

- Shade for leisure activities

- Lower energy costs for cooling

- Cover and food for wildlife

- Screen from unsightly views

- Privacy from neighbors

- Addition of value to your property; click here to determine the monetary value of a tree

If you have plenty of trees already, consider getting involved in a local community group that is sponsoring Arbor Day tree plantings. Or maybe your local church, park, non-profit or school would appreciate the donation and planting of a new tree.

So what trees are best to choose for the Florida panhandle? Some things to consider are soil type and pH, light, and any overhead obstructions. Click here for a publication that discusses what to consider when choosing a tree. Florida Trees for the Urban and Suburban Landscape will help you choose a particular tree species for your site. Considerations in tree selection may include bloom color and season, mature size, hurricane resistance, and whether it is evergreen or deciduous.

Once you have chosen a great tree for your specific site, proper installation and care is crucial to the success of your new tree. Click here to learn all about planting and caring for your tree.

For more information please see:

Arbor Day Foundation: Florida

Native Trees for North Florida

Palms for North Florida

Planting Trees in Landscapes

National Tree Benefit Calculator

by Sheila Dunning | Dec 17, 2013

Removal of the container and inspection of the rootball is critical to tree survival.

The best time to plant a tree is twenty years ago. The second best time is Arbor Day 2014. Florida recognizes the event on the third Friday in January, so the next one is January 17, 2014.

Arbor Day is an annual observance that celebrates the role of trees in our lives and promotes tree planting and care. As a formal holiday, it was first observed on April 10, 1872 in the state of Nebraska. Today, every state and many countries join in the recognition of trees impact on people and the environment.

Trees are the longest living organisms on the planet and one of the earth’s greatest natural resources. They keep our air supply clean, reduce noise pollution, improve water quality, help prevent erosion, provide food and building materials, create shade, and help make our landscapes look beautiful. A single tree produces approximately 260 pounds of oxygen per year. That means two mature trees can supply enough oxygen annually to support a family of four.

The idea for Arbor Day in the U.S. began with Julius Sterling Morton. In 1854 he moved from Detroit to the area that is now the state of Nebraska. J. Sterling Morton was a journalist and nature lover who noticed that there were virtually no trees in Nebraska. He wrote and spoke about environmental stewardship and encouraged everyone to plant trees. Morton emphasized that trees were needed to act as windbreaks, to stabilize the soil, to provide shade, as well as, fuel and building materials for the early pioneers to prosper in the developing state.

Proper planting depth and adequate watering can ensure long-term survival.

In 1872, The State Board of Agriculture accepted a resolution by J. Sterling Morton “to set aside one day to plant trees, both forest and fruit.” On April 10, 1872 one million trees were planted in Nebraska in honor of the first Arbor Day. Shortly after the 1872 observance, several other states passed legislation to observe Arbor Day. By 1920, 45 states and territories celebrated Arbor Day. Richard Nixon proclaimed the last Friday in April as National Arbor Day during his presidency in 1970.

Today, all 50 states in the U.S. have official Arbor Day, usually at a time of year that has the correct climatological conditions for planting trees. For Florida, the ideal tree planting time is January, so Florida’s Arbor Day is celebrated on the third Friday of the month. Similar events are observed throughout the world. In Israel it is the Tu B Shevat (New Year for Trees) on January 16, 2014. Germany has Tag des Baumes on April 25. Japan and Korea celebrate an entire week in April. Even, Iceland one of the treeless countries in the world observes Student’s Afforestation Day.

The trees planted on Arbor Day show a concern for future generations. The simple act of planting a tree represents a belief that the tree will grow and some day provide wood products, wildlife habitat erosion control, shelter from wind and sun, beauty, and inspiration for ourselves and our children.

Clayton ( Sheila’s grandson) will reap the benefits of the trees planted this Arbor Day.

“It is well that you should celebrate your Arbor Day thoughtfully, for within your lifetime the nation’s need of trees will become serious. We of an older generation can get along with what we have, though with growing hardship; but in your full manhood and womanhood you will want what nature once so bountifully supplied and man so thoughtlessly destroyed; and because of that want you will reproach us, not for what we have used, but for what we have wasted.”

~Theodore Roosevelt, 1907 Arbor Day Message

by Larry Williams | Dec 17, 2013

Common symptoms of the black twig borer. Image Credit Matthew Orwat UF IFAS Extension

Q. Small branches are dying in some of my trees. What’s causing this?

A. More than likely the culprit is the Black Twig Borer. This very small beetle, about 1/16 inch long, has been active this year.

Common trees attacked include cedar, golden rain tree, maple, redbud, sweetgum, loquat, dogwood, Shumard oak, Chinese elm, magnolia, Bradford pear and pecan. The beetle is not limited to these trees. And it may attack woody shrubs and grapevines.

Black Twig Borer Entry Holes. Image Credit Matthew Orwat UF IFAS Extension

Black Twig Borer Entry Holes. White Frass Visible. Image Credit Matthew Orwat UF IFAS Extension

This beetle only damages branches that are approximately pencil size in diameter. These small branches die above the point of entrance with the leaves turning brown, creating a flagging effect of numerous dead branches scattered throughout the outer canopy of the tree. These dead twigs with their brown leaves are what bring attention to the infested trees.

Bending an infested twig downward will result in it snapping or breaking at the entrance/exit hole. Carefully putting the twig back together may allow you to see the hole. The hole is usually on the underside of the branch and will be very small, about the size of pencil lead in diameter. Sometimes you may see the minute, shiny black beetle and/or the white brood inside the hollowed out area of the twig at the point where it snapped.

Black Twig Borer inside the stem. Image Credit Matthew Orwat UF IFAS Extension

The black twig borer, Xylosandrus compactus, is one of the few ambrosia beetles that will attack healthy trees. However, the heavy rainfall this summer stressed many of our tree and plant species making them more susceptible to insect damage and disease.Female beetles bore into small branches or twigs of woody plants, excavate tunnels in the wood or pith and produce a brood. Damage occurs when the beetle introduces ambrosia fungi on which the larvae feed. The beetles emerge in late February, attack twigs in March and brood production begins in April. Highest population levels occur from June to September. Adults spend the winter in damaged twigs and branches. So it’s important to pickup and dispose of the small branches as they fall.

Where practical, the best control is to prune tree limbs 3-4 inches below the infested area, then remove and destroy the limbs. Proper mulching, avoiding over fertilization and irrigating during dry weather should improve tree health, allowing trees to better withstand attacks. Chemical controls are usually not practical or effective.

Entry point from a different angle. Image Credit Matthew Orwat UF IFAS Extension

Additional information on this beetle is available though the UF IFAS Extension Office, your County Forester or online at the UF IFAS Featured Creature page