by Daniel J. Leonard | Oct 14, 2020

Article by Jessica Griesheimer & Dr. Xavier Martini, UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center, Quincy

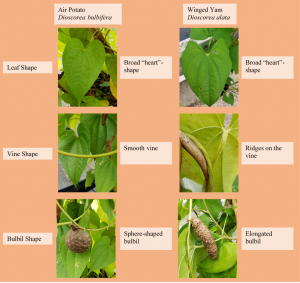

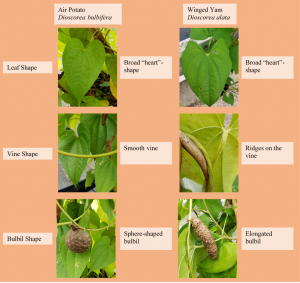

Dioscorea bulbifera, commonly known as the air potato is an invasive species plaguing the southeastern United States. The air potato is a vine plant that grows upward by clinging to other native plants and trees. It propagates with underground tubers and aerial bulbils which fall to the ground and grow a new plant. The aerial bulbils can be spread by moving the plant, causing the bulbils to drop to the ground and tubers can be spread by moving soil where an air potato plant grew prior. The air potato is commonly confused with and mistaken as being Dioscorea alata, the winged yam which is also highly invasive. The plants look very similar at first glance but have subtle differences. Both plants exhibit a “heart”-shaped leaf connected to vines. The vines of the winged yam have easily felt ridges, while the air potato vines are smooth. They also differ in their aerial bulbil shapes, the winged yam has a long, cylinder-shaped bulbil while the air potato aerial bulbil has a rounded, “potato” shape (Fig. 1).

In its native range of Asia and Africa, the air potato has a local biocontrol agent, Lilioceris cheni commonly known as the Chinese air potato beetle (Fig. 2). As an adult, this beetle feeds on older leaves and deposits eggs on younger leaves for the larvae to later feed on. Once the larvae have grown and fed, they drop the ground where they pupate to later emerge as adults, continuing the cycle. The Chinese air potato beetle will not feed on the winged yam, as it is not its host plant.Current methods of air potato plant, bulbil, and tuber removal can be expensive and hard to maintain. The plant is typically sprayed with herbicide or is pulled from the ground, the aerial bulbils are picked from the plant before they drop, and the underground tubers are dug up. The herbicides can disrupt native vegetation, allowing for the air potato to spread further should it survive. If the underground tuber or aerial bulbils are not completely removed, the plant will grow back.

The Chinese air potato beetle is currently being evaluated as a potential integrated pest management (IPM) organism to help mitigate the invasive air potato. The beetle feeds and reproduces solely on the air potato plant, making it a great IPM organism choice. During 2019, we studied the Chinese air potato beetle and its ability to find the air potato plant. It was found the beetles may be using olfactory cues to find the host plant. Further research is conducted at the NFREC to increase natural aggregation of the beetles on air potato to improve biological control of the weed.

Chinese Air Potato Leaf Beetle.

If you have the air potato plant, or suspect you have the air potato plant, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Agents for help!

by Carrie Stevenson | Aug 14, 2020

Tasty, edible muscadine grapes are ripening in northwest Florida now. Photo credit: Jennifer Shiver

There is something deeply satisfying about plucking fruit off a plant growing outside and tasting it right off the vine/bush/tree. Since childhood, I have reached carefully through the tiny and numerous thorns of blackberry bushes growing in the woods, hoping the berry I’d worked for was more sweet than tart. One vine-ripe fruit that never disappoints, however, is the native muscadine grape (Vitis rotundifolia). Granted, before eating for the first time you have to be aware that the thick skin will give way to a gelatinous goo with several seeds, but their refreshing taste on a hot summer day is unlike any other. Beloved by deer and other mammals and birds of all types, it’s hard to find a lot of muscadine grapes available in the woods because the wildlife has likely beaten you to them. You can find their unique leaves year-round, though, so at least you know where to look once the grapes start to form. I would be remiss if I didn’t mention these grapes also go by the term “scuppernong”, which is a colloquial term for the lighter green/bronze (and more common) muscadines in the southeast.

Muscadines are grown commercially for the wine industry throughout Florida.

While tasty on their own, muscadines are most prized for making jelly and wine. We used to have an older Southern Baptist deacon and neighbor who would slip us both, with a wink and an implied promise not to tell the preacher about the wine. Winemaking in Florida is an old tradition, and several local wineries specialize in these sweeter wines, like Chatauqua in DeFuniak Springs. They are often blended with other fruits like blueberry and strawberry. Our Extension colleagues with the Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University (FAMU) have a widely recognized viticulture program, and I recommend their resources if you are interested in growing muscadines yourself.

As for wild muscadines, you can find the vines all over the place, from shady forests to sunny beach dunes. The vines can be up to 100 feet long, climbing with the help of small tendrils. Inconspicuous greenish white flowers form in late spring, with fruit ripening in late summer/early fall. It serves you well to learn field identification for the muscadine, as it is a sweet treat on a hot Florida day.

by Carrie Stevenson | Feb 18, 2020

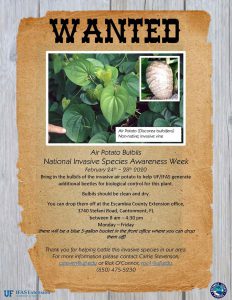

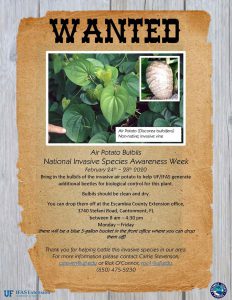

Several Extension offices in the Panhandle are collecting air potato bulbils for National Invasive Species Week. Photo credit: Esther Mudge, Escambia County

The non-native invasive air potato vine (Discorea bulbifera) has wound its way throughout Florida, from pine forests and creek floodplains to backyards. Their heart-shaped leaves are most noticeable in the spring and fall, where they can take over large areas, not unlike their fellow invasive vine, kudzu. In the fall, the plant produces a potato-like tuber called a bulbil, which grows above ground on the vine. The bulbils drop in the winter and then produce new vines the following spring.

The vine’s growth has been uncontrolled or kept back by herbicide for years, until researchers discovered a biological control insect known as the air potato leaf beetle (Liloceris cheni). In the vine’s native Nepal and China, the beetle controls growth by surviving on the leaves of the air potato, its sole food source. After extensive study, the USDA approved the use of these beetles in Florida to control the air potato vine population here. UF IFAS Extension offices statewide have participated in these beetle release programs, providing thousands of beetles to homeowners and property owners seeking to manage the invasive vine using a chemical-free technique. Left alone, air potato vines can smother full-sized trees, blocking the sunlight and causing them to collapse under the weight of the intertwined vines.

From 2012-2015, beetles were able to reduce air potato vine coverage and bulbil density by 25-70% (depending on location and density of beetle population). The active beetle-production phase of a UF IFAS grant has ended, but researchers are committed to the goal of reducing this nuisance species statewide.

To assist with this process, several Extension offices in the Panhandle are sponsoring a bulbil collection during National Invasive Species Week (NISAW, February 23-29). This effort will serve two important roles: to remove bulbils from the natural environment and to provide a seed source for university researchers seeking to grow air potato vine in a controlled environment, sustaining a continued population of air potato beetles for distribution.

For more information on Air Potato Vines and Leaf Beetles, visit https://bcrcl.ifas.ufl.edu/airpotatobiologicalcontrol.shtml or contact your local County Extension office.

by Julie McConnell | Jul 25, 2019

As an avid gardener and plant collector you might think I’m hyper-aware of everything growing in my yard. Sadly, I’m just as busy and forgetful as the next person and don’t always remember what’s out there. The silver lining to the distracted auto-pilot life we find ourselves in is that occasionally you get brought back into the moment by a show stopping surprise in the garden.

Bleeding Heart Vine is one of those garden gems. Planted in the bright shade of a pair of oak trees in my Northwest Florida yard, the dark green foliage blends into the background most of the year, but when it flowers look out! Panicles of 5-20 white and red flowers brighten up the shady garden. As the flowers fade, they turn a deep mauve that is just as attractive as the fresh flowers.

Some vines can be aggressive growers, but in the Florida Panhandle Bleeding Heart Vine is a relatively slow grower reaching about 15 feet at maturity. It is classified as a twining vine, but may need a little help supporting itself on a trellis. This vine lacks tendrils or suckers that some vines use to attach to structures, which makes it a little easier to redirect if it starts to grow in an undesirable direction. Don’t want it to climb? Prune to stimulate branching and it gets more of a sprawling, bushy shape.

Bleeding Heart Vine prefers moist, well-drained soil and high humidity. It is hardy to 45°F and may need protection in the winter. Personal observations of this plant have shown stem dieback in the winter, but it has grown back for multiple years without protection in Northern Bay County.

Reference and further information at Floridata Plant Profile #1053 Clerodendrum thomsoniae

by Les Harrison | Aug 23, 2016

Air potato leaf beetle. Photo credit: Les Harrison, UF/IFAS.

A small, but brightly colored beetle has appeared in north Florida: the air potato leaf beetle (Liliocetis cheni), a native of East Asia. The beetle, less than half an inch long, has a candy apple red body that stands out against green leaves and the more muted earth tones of most other bugs. The striking bright glossy red coating would be the envy of any sports car owner or fire truck driver.

Unlike other arrivals to the U.S., this insect was deliberately released in 2012 for biological control of air potato. After years of testing, approval was finally given to release air potato leaf beetles to begin their foraging campaign against this invasive plant species. The beetle has very specific dietary requirements and only can complete its life cycle on air potato. The larvae and adults of this species consume the leaf tissue and occasionally feed on the tubers.

When a population of air potato leaf beetles finish off an air potato thicket, they go in search of nourishment from the next patch of air potato. They are sometimes seen during stopovers while in search of their next meal.

Air potato (Dioscorea bulbifera) is an herbaceous perennial vine which is easily capable of exceeding 60 feet in length. It quickly will climb over any plant, tree or structure unfortunate enough to be in its vicinity. The vine also produces copious quantities of potato-like tubers suspended from its vines. Unless collected and destroyed, most of the easily camouflaged potatoes will germinate and intensify the infestation.

Air potato. UF/IFAS Photo: Thomas Wright.

Air potato came to Florida in 1905 from China and quickly escaped into the wild. By the 1980’s it was a serious pest species in south and central Florida, but has gradually become established in the panhandle, too. Chemical control of the air potato has been difficult. Repeated herbicide treatments are required to kill a thicket with multiple plants.

Unlike the air potato leaf beetle that only eats air potato, kudzu bugs eat their namesake vine (kudzu), but also feed on a number of other plants including a wide selection of valuable legumes and be quite destructive. Kudzu bugs were accidently introduced in north Georgia in 2009 and have spread across the south in the ensuing years and become established in north Florida.

It is a pleasant surprise to know air potato leaf beetles are working to limit the invasive air potato vine, but it is sad to think there is plenty more for them to eat.

To learn more about the air potato and the beetle:

Natural Area Weeds: Air Potato (Dioscorea bulbifera)

Air Potato Leaf Beetle Publication

by Mark Tancig | Aug 19, 2016

Skunkvine illustration. UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants.

North Florida gardeners have many non-native, invasive plants to deal with, but none quite as stinky as skunkvine (Paederia foetida). As the name implies, skunkvine has a noticeable smell, especially when the leaves are crushed, and it is an aggressive-growing vine, capable of smothering desirable landscape plants. Gardeners should learn to recognize and control this plant before it gets a foothold in the garden.

Skunkvine is native to eastern and southern Asia and a member of the coffee family (Rubiaceae). It was introduced to Florida prior to 1897 as a potential fiber crop, but quickly spread and is now considered a Category I invasive plant by the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council (FLEPPC) and as a noxious weed by the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Sciences (FDACS).

Skunkvine can be identified by the following characteristics:

- Aggressive twining vine

- Leaves are opposite each other

- There is a thin flap of tissue on the stem between the leaves

- Leaves have a strong skunk-like odor when crushed

- Clusters of small, tubular, lilac-colored flowers appear in late summer to fall

- Fruits are shiny brown and can persist through winter

Skunkvine flowering. Photo by Ken Ferrin, UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Once you have identified skunkvine in your garden, the next step is to work to remove it. For small patches, pulling by hand can be effective but will require monitoring to ensure it doesn’t resprout. When hand pulling, you want to be sure to get as much of the root as possible. For larger areas, chemical control using herbicide products that contain triclopyr, imazapic, or aminopyralid are most effective. Carefully reading the product label will help determine which product to purchase.

Since skunkvine can be easily spread by seed and fragments of stem, care must be taken when disposing of it. The best solution is to place plant debris into a trash bag and dispose of it with your regular household garbage.

By knowing how to identify and manage skunkvine, north Florida gardeners can keep it from stinking up their own gardens, their neighbor’s gardens, and surrounding natural areas that support our native wildlife.

References:

Langeland, K. A., Stocker, R. K., and Brazis, D. M. 2013. Natural Area Weeds: Skunkvine (Paederia foetida). Agronomy Department, Florida Cooperative Extension Service, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida. EDIS document SS-AGR-80.