by Evan Anderson | Jun 24, 2021

There are lots of plant pests out there, and it can take a trained eye to tell which one is doing damage. Many of the insect pests that feed on crops and ornamentals have piercing-sucking mouthparts. These insects do not chew on leaves and leave holes behind; instead, they have a long stylus-like mouthpart they use like a straw to suck out plant juices. Over time this can weaken plants, cause irregular growth as damage builds up on new sprouts, introduce diseases to their hosts, and even cause mold to grow on leaves.

Because they drink so much fluid for their meals, many piercing-sucking insects exude a sugary liquid called honeydew. This liquid drops onto stems and leaves below which can leave them shiny and sticky. Eventually, the coating will grow a light greyish coating of sooty mold, which doesn’t do much harm to the plants itself but is a good indicator that you have an insect problem. You may also notice ants on your plants, working to harvest the honeydew for food. The ants don’t harm the plant, but following are some of the pests that do:

Aphids feeding on a plant stem.

A parasitic wasp emerging from a dead aphid.

Aphids – Found on a wide variety of plants, aphids are fat-bodied little insects that often focus on new, tender growth. Their color depends on the plant they’re feeding on, and they can breed explosively. A female aphid does not need to mate to produce offspring, so a one can produce a lot of children very quickly. Look closely and you might be able to see their cornicles, which look like little tailpipes; these can help identify these pests. Luckily, we have some help in controlling aphids, as they are often parasitized by wasps. If you see large, swollen, brown aphids present, you probably have some wasps working for you.

Ants tending some scale insects on a stem.

Scale Insects – Sometimes appearing to just be a bump on a stem or leaf, scale insects don’t move once they pick a plant to live on. Prolific producers of honeydew, some species grow a waxy shell which can protect them and make them difficult to deal with.

A mealybug.

Mealybugs – If you spy something white and fluffy living on stems or leaves, you might have mealybugs. Soft-bodied insects that are related to scales, they don’t move much. They feed on a wide range of host plants, but can effectively be controlled with a variety of methods once they’re found.

Whiteflies on the underside of a leaf.

Whiteflies – Not true flies, they are truly white in color. Tiny little members of the order Hemiptera (the same order that includes, aphids, scales, and mealybugs), they hang around the undersides of leaves. They enjoy warm weather and can become a problem in greenhouses. They are a bit more difficult to control than some of the other pests listed here.

A psyllid nymph hiding in its waxy coating.

Psyllids and planthoppers – Small jumping insects that affect a variety of plant species, some are responsible for transmitting important plant diseases. Pierce’s disease of grapes and citrus greening, for example, are both vectored by these critters. Young nymphs sometimes secrete a waxy coating which may make them look similar to mealybugs.

A tiny two-spotted spider mite.

Spider Mites – Not an insect but an arachnid, spider mites love hot, dry weather. Almost microscopic in size, the damage they do to leaves is often the first sign that they are present. Looking closely, one might notice tiny webbing where the mites live, or even the mites themselves on the undersides of leaves and on stems.

Many of these pests can be treated with a combination of methods. A sharp jet of water can dislodge some, hand removal can reduce populations even more, and products such as insecticidal soap or horticultural oils can finish them off. Insecticidal soaps are best used on soft-bodied insects such as aphids or mealybugs, while oils such as neem can help suffocate hard scales. Use products such as horticultural oil in the evening during hot weather to avoid damaging plant tissues with intense sunlight. Thorough coverage is important, as these products only control the pests they contact.

For more information on controlling insects, see our EDIS publications, such as Insect Management in the Home Garden or Landscape Integrated Pest Management.

by Ray Bodrey | Jun 24, 2021

We have many choices of fruit that can be grown in the Florida Panhandle. For us hobby or dooryard growers, fruit trees can be an interesting crop to manage and most find it to be a beautiful addition to home landscapes. However, temperature and variety selection are key.

Blueberry Crop at UF/IFAS Plant Science Research & Education Unit. Photo Credit: Tyler Jones, UF/IFAS

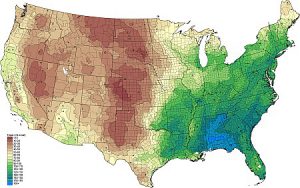

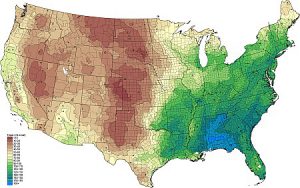

Most fruit trees grown in the Panhandle are more temperate varieties, rather than tropical and subtropical fruits. Depending on the variety, winters in northern Florida may be too cold or may be too long for some fruit trees. Cold hardiness is a term used on fruit tree labels and reference guides. This refers to the plant’s ability to survive cooler or even freezing temperatures. In contrast, summer heat can also play a role in survivability. Some varieties are intolerant to excessive heat and humidity. The U.S. Department of Agriculture has developed a Plant Hardiness Zone Map that is helpful in selecting a variety of fruit tree: http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/. This is a standard by which gardeners and growers can determine which plants will thrive in their location. Northern Gulf County is in Zone 8b (15 to 20 degrees F), while coastal Gulf is in Zone 9a (20 to 25 degrees F).

Chilling requirement is another important topic when deciding on variety. Temperate zone fruit go through a “rest period” during the dormant months. For these fruit trees, a minimum length of time of cooler weather is needed for proper flowering to occur once favorable temperatures arrive. This rest period is essentially a reset. For the Panhandle, temperatures below 45 degrees F are known as chilling temperatures. The number of hours during the fall and winter that reach below this temperature equals the total chilling hours. For the Panhandle, this is rarely fewer than 500 hours. A plant that does not receive ample chilling will most likely be slow in bud and leaf development. Leaf expansion will be in increments throughout the year instead of in one period. On the other hand, colder, longer winters can cause fruit trees to end the rest stage early and begin to bud as soon as warmer temperatures arrive. This circumstance can cause cold injury later, as the Panhandle is historically known for late cold spells.

Citrus is a dooryard fruit, however it’s a subtropical fruit tree and not technically temperate. However, there are some varieties that thrive in the Panhandle. Another key to growing citrus, is to select varieties with different fruit maturity seasons. This way you can enjoy citrus year-round.

Some examples of dooryard fruit trees and varieties that are suitable for northern Florida are:

Apple: ‘TropicSweet’, ‘Anna’, ‘Dorsett Golden’

Blueberry: ‘Rabbiteye’, ‘Climax’, ‘Highbush’

Grapefruit: ‘Marsh’, ‘Ruby Red’

Lemon: ‘Myer’

Nectarine: ‘Suncoast’

Orange/Mandarin: ‘Navel’, ‘Parson Brown’, ‘Valencia’, Satsuma

Peach: ‘Gulfcrest’, ‘Gulfking’, ‘Gulfprince’

Pear: ‘Ayers’, ‘Baldwin’, ‘Kieffer’

Pecan: ‘Elliot’, ‘Stuart’, ‘Moreland’

So, where do I find information on varieties? The UF web publication “Dooryard Fruit Varieties” is a great resource. Also contact your local county extension office for more information.

Information for this article can be found in the UF/IFAS EDIS publication: “Dooryard Fruit Varieties” by J. G. Williamson, J. H. Crane, R. E. Rouse, and M. A. Olmstead: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/MG/MG24800.pdf

UF/IFAS Extension is an Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Gary Knox | Jun 17, 2021

‘Disney’ scarlet ginger lily produces beautiful orange flower clusters atop stems growing up to 7 feet in height

If you’re looking for colorful flowers with superpowered fragrance, look no farther than ginger lily (Hedychium sp.). This group of plants packs a punch with big, bright flowers, intoxicating fragrance and bold tropical foliage, all in a robust herbaceous perennial that is perfectly hardy in north Florida.

Ginger lilies are tropical and subtropical plants in the Zingiberaceae (Ginger) Family. They produce fragrant, colorful, complex flowers and often other plant parts also are aromatic. Ginger lily flowers appear in racemes or spikes at the tops of cane-like stems 4 to 6 feet or more in height. Flowering summer until frost, the clumps of upright stems grow from thick rhizomes that creep underground just below the soil surface. Native to Asia and related to the spice, true ginger (Zingiber officinale), ginger lilies will add color, fragrance and a tropical vibe to your home garden.

Ginger lilies grow best in full to part sun in rich, moist, well-drained soil. New stems emerge in late spring and quickly grow into upright stems with long, bold-textured leaves held horizontally or angled upright. The cane-like stems are topped with clusters of large, bright colored flowers starting in late spring to mid summer, often continuing through fall. Frosts or freezes will kill the above-ground stems, but rhizomes easily overwinter temperatures as low as 0°F (making them hardy into USDA Cold Hardiness Zone 7b) and produce new growth in late spring once warm weather resumes. Few pests or diseases affect ginger lily, and the only regular maintenance is to cut and remove the dead stems in late winter before new growth emerges.

Butterfly ginger is the type most widely grown and frequently shared as a pass-along plant. Butterfly ginger (Hedychium coronarium) is grown for its large fragrant white flowers. It grows 4 to 5 feet high and begins flowering in mid to late summer, continuing through fall. With a heavy sweet fragrance, a flowering clump of butterfly ginger smells heavenly in the garden and, as a cut flower, will easily perfume a large room! Butterfly ginger is not picky about growing conditions but prefers moist, good garden soil. This is the ginger flower most often used to make Hawaiian leis!

There are dozens of species and cultivars of Hedychium. Some of the ginger lilies that are often found in local nurseries or Master Gardener plant sales are listed below.

‘Dr. Moy’ variegated ginger lily (Hedychium ‘Dr. Moy’) is distinguished by white paint-like splashes on its leaves and fragrant, peachy-orange flowers. ‘Dr. Moy’ produces its first round of flowers from mid-July to August and a second crop in late-September to October.

‘Daniel Weeks’ ginger lily (Hedychium ‘Daniel Weeks’) is a perennial tropical ginger hybrid from Florida’s Russell Adams with hardiness to Zone 7. Growing to 6 to 7 feet high, it produces large dark throated golden-yellow inflorescences with the bonus of delightful evening fragrance. This vigorous clumping hardy ginger lily is the longest blooming, starting in early to mid summer and continuing to frost. It is considered by many as one of the best of all ginger lilies.

‘Disney’ scarlet ginger lily (Hedychium coccineum ‘Disney’) produces large, bright orange flower clusters on tall stems up to 7 feet in height. Foliage is very glossy with a reddish hue, and the overall effect of the clump of stems is very upright. Typically, all stems flower at the same time followed by a resting period before flowering again.

‘Pink Sparks’ ginger lily (Hedychium ‘Pink Sparks’) is a compact variety only growing 4 to 5 feet high. Terminal inflorescences are made up of many small bright pink flowers with very long stamens.

Ginger lily may be propagated by digging and dividing clumps or by cutting off sections of rhizome (making sure each section has at least one bud) and placing these in new locations for sprouting and growth. It’s best to divide or propagate plants before late summer so divisions have enough time to develop a new root system and/or stems before the cooler weather of fall slows growth.

References

Carey, Dennis and Tony Avent. 2010. Hedychium – A Hardy Ginger Plant for the Garden. Plant Delights Nursery, Inc., Raleigh, NC 27603. https://www.plantdelights.com/blogs/articles/ginger-plant-lily-variegated-hedychium-lilies. Accessed 9 June 2021.

Gilman, Edward F. 2015. Hedychium coronarium Butterfly Ginger, FPS-240. Environmental Horticulture Department, UF/IFAS Extension, Gainesville, FL 32611. Original publication date October 1999. Reviewed February 2014. FPS-240/FP240: Hedychium coronarium Butterfly Ginger (ufl.edu). Accessed 9 June 2021.

by Mark Tancig | Jun 17, 2021

Spending time outdoors during the Florida summer is not for the faint of heart. It’s hot! And it’s humid! Just moving around outside for a moment in the early morning causes you to break out in a sweat. Most evenings, even after the sun is low in the western sky, but there’s still enough light to enjoy the outdoors, the sweat doesn’t stop. A Floridian’s only hope is that nearby, there is a large shade tree to take cover under. In north Florida, there’s nothing more inviting than a huge live oak draped in Spanish moss for a drink of ice water and a slight breeze. If you don’t have such a spot, start thinking about planting a shade tree this winter!

A large live oak is great for shade! Credit: Dawn Reed.

In north Florida, we have many options to choose from, as we live in an area of the United States with some of the highest native tree abundance. Making sure you get the right tree for the right place is important so make a plan. Where could this tree go? Is there plenty of space between the tree and any structures? You’ll want to give a nice shade tree plenty of room – 20’ to 60’ away from structures and/or from other large trees – to grow into a great specimen. Be sure not to place a large tree under powerlines or on top of underground infrastructure. You can “Call 811 before you dig” to help figure that out. If space is limited, you may want to consider trees that have been shown to be more resilient to tropical weather. Also try and place the tree in a way that provides added shade to your home. Deciduous trees planted along your home’s southeast to southwest exposure provide shade during the summer and let in the sun during the cooler winter. However, be careful that the tree doesn’t grow to block the sun from your vegetable garden!

A density gradient map of native trees in the US. Notice where the highest number occur. Credit: Biota of North America Program.

Here are some ideas for shade trees, those trees that are tall (mature height greater than 50’) and cast a lot of shade (mature spread greater than 30’). All of these are native trees, which have the added benefit of providing food and shelter to native wildlife.

- Red maple (Acer rubrum)

- Pignut hickory (Carya glabra)

- Green ash (Fraxinus pennsylvanica)

- Tulip poplar (Liriodendron tulipifera)

- Southern magnolia (Magnolia grandiflora)

- Sycamore (Platanus occidentalis)

- Shumard oak (Quercus shumardii)

- Live oak (Quercus virginiana)

- American elm (Ulmus americana)

It’s best to plant during the winter and follow good planting practices.

Even with this young sycamore, you’ll be made in the shade. Credit: UF/IFAS.

While it may take a while for you to relax under the shade of your tree, they can surprise you in their growth and, as they say, there’s no time like the present. If you have questions on selecting or planting shade trees, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office.

by Matt Lollar | Jun 17, 2021

A month or so ago I was leaving for work and I noticed a strange substance near the entrance to the house. The substance was blue and my first thought was crushed chalk from my kids writing on the sidewalk. Upon closer investigation I realized the substance was moving! It was now clear to me that the substance wasn’t chalk, but a congregation of insects. Naturally, I took pictures and collected a sample to bring into the county extension office…where I work. I looked at the insects under the microscope, but I wasn’t able to determine the species. So I sent some samples off to the University of Florida/IFAS Entomology and Nematology Department and the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services.

A swarm of Desoria flora on damp, outdoor steps. Photo Credit: Matt Lollar, University of Florida/IFAS Extension – Santa Rosa County

The experts identified the specimens as Desoria flora, a species of springtail insects endemic to Florida and originally described in Alachua County in 1980. Both entomologists thought it was unique the springtails were swarming. Springtails live in leaf litter and upper layers of soils. They are sometimes found in the potting mix of indoor and outdoor plants. Clients bring springtail specimens in to the office for identification from time to time. However, this was the first time I had seen them in a congregation.

A linear springtail. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS

If you find interesting insects, plants, or fungi and want them identified, please bring them into your local Extension Office. We’d be happy to help you identify the specimens. But sometimes we have to mail things off to a specialist.