by Carrie Stevenson | Dec 18, 2024

A large Carolina wolfberry shrub thrives near St. Marks’ lighthouse at the wildlife refuge. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

I was lucky enough to spend a weekend in November exploring a lovely, low-key stretch of northwest Florida. We hiked trails and took the boat tour at Wakulla Springs State Park, marveling at the numerous alligators and admiring birds and a slow-moving manatee. We also hiked through St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge, which is home to a nearly 200-year-old lighthouse and keeper’s house, which have a fascinating history of their own.

The brilliant red, and edible, berry of the Carolina wolfberry is ripe in late fall/early December. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Exploring the shoreline of Apalachee Bay behind the lighthouse, we watched fiddler crabs run the salt flats and herons quietly stalk their prey. Always on the lookout for something new, I noticed a large shrub growing several yards back from the beach. It looked like a cross between a rosemary and a holly, with delicate lavender/purple flowers and brilliant red teardrop-shaped fruit. I’d never seen it before.

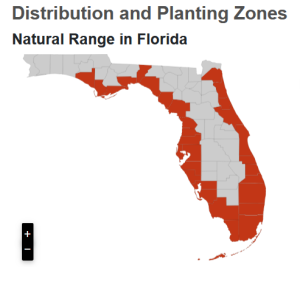

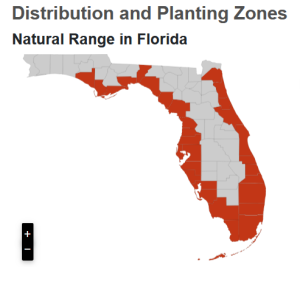

Map of the natural range of Carolina wolfberry in Florida. Figure courtesy of the Florida Native Plant Society.

After a quick investigation, I learned it was a Carolina wolfberry, aka Carolina deserthorn, aka Christmas berry (Lycium carolinianum). The invasive species coral ardisia (Ardisia crenata) is also known in some areas as Christmas berry—this is why scientific names are so useful—but that is not the plant we saw at St. Marks. The native Carolina wolfberry was located right where you might expect it, on dry coastal scrub, in view of the saltwater it easily tolerates. Its native range in Florida starts along the coastline east of here, particularly Bay and Wakulla counties and all the way down around the state.

The delicate lavender flower of the Carolina wolfberry is a popular nectar source for native butterflies. Photo credit: Peggy Romfh

The tall shrub is evergreen, with leaves adapted into a long, thin, slightly succulent near-needle shape. This leaf form helps hold water in a dry, salty environment and prevents evaporation. The tips of the shrub’s branches have thorns, hence the common name “desert-thorn.” Carolina wolfberry produces those attractive little purple blooms in the fall, providing nectar for several species of native butterflies. In late fall/early winter, the brilliant red fruits show up. They are less than an inch long and reminiscent of peppers. When ripe, the fruit are edible and are described as sweet and tomato-like. The fruit are not only popular for human consumption, but also for birds, deer, and raccoons. Just before we walked down the beach, another visitor saw a bobcat disappear into the shrub, which provides cover for many additional species besides those who eat it directly.

Illustration from a 15th century plant medicine book showing the mandrake, a member of the Solanaceae family.

Carolina wolfberry is a member of the Solanaceae family, aka nightshade (sometimes referred to as “deadly nightshade”). Other relatives include edible tomatoes, peppers, potatoes, eggplant, and groundcherry. The “deadly” part refers to related species like belladonna and mandrake, from which toxic poisons can be extracted. If you’re looking for a fascinating historical deep dive into these plants’ connection to witches, Shakespeare, and the death of multiple Roman emperors, look no further than the US Forest Service’s web page on the “Powerful Solanaceae” family!

by Joshua Criss | Nov 21, 2024

A Sea of Yellow

You do not often see a sea of yellow flowers on what was recently a field of row crops in North Florida. In this instance, the culprit is a cover crop called sunn hemp (Crotalaria juncea). Cover cropping, or green manure as it is sometimes known, is not a new concept. It is a great method for improving soil quality, adding organic matter, augmenting nitrogen supply, supporting pollinators when resources begin to wane, and combating nematodes. Incorporating this sustainable agriculture practice into home vegetable gardens is an excellent method to build long-term viability and production.

Many plants may be used in this capacity, but this article will focus on sunn hemp. This annual is an herbaceous, short-day flowering plant in the Lamiaceae or legume family. Its erect stems produce a great deal of biomass and, as a legume, will augment nitrogen stores within your soil profile. As if that wasn’t enough to sell you, this plant is also known to suppress nematode populations. Native to India and Pakistan, where sunn hemp is grown for fiber, this plant grows well in tropical and temperate environments. It will thrive in even sub-par conditions and requires little fertilizer input.

UF/IFAS Photo: Josh Criss

Seed Time

Seed this plant once your summer gardens have begun to wane. The shorter day length will keep the plant confined to about 3-4 feet while still allowing it to flower. It may also be planted earlier in the year to maximize below-ground biomass and add organic matter. In this scenario, the plant will likely grow to 7 feet tall with a closed canopy within 10 weeks.

Sunn hemp requires little fertilization as it is a legume, a plant family known to fix nitrogen from the atmosphere. This same mechanism is one of the features of this plant as a cover or green manure crop, as it can add up to 320 pounds of nitrogen per acre back to the soil when planted en masse.

Seeding rates within a home garden are much smaller. A farmer may plant 30-50 pounds of seed, which is not practical in small-scale growing. Instead, aim to cover the garden area through broadcasting seed, as a denser planting will reduce the later branching of this plant. Ensure you have 8-12 weeks of warm, frost-free weather, and terminate them prior to reaching the full bloom stage. Doing so will provide your gardens with the same benefits seen in farm fields utilizing this sustainable practice.

UF/IFAS Photo: Josh Criss

To Sum it Up

Sunn hemp is an excellent plant for your gardens before your fall greens. The biomass it produces and the nitrogen it recovers make it very attractive to farmers and should raise eyebrows even in the home garden. The trick is learning to manage this plant within your crop rotation. For more information on soil management refer to these IFAS documents, or contact your local extension agent for additional information on this and any topic regarding your gardens and more.

by Sheila Dunning | Nov 6, 2024

Red Maple structure IFAS Photo: Hassing, G.

Though the calendar says November, the weather in Northwest Florida is still producing summer or at least spring-like temperatures. The nice days are wonderful opportunities to accomplish many of those outside landscape chores. But, it is also a good time to start planning for next month’s colder temperatures. Since we don’t experience frozen soil, winter is the best time to transplant hardy trees and shrubs. Deciduous trees establish root systems more quickly while dormant; versus installing them in the spring with all their tender new leaves.

Remove an inch or more for extremely rootbound trees.

Here are a few suggestions for tasks that can be performed this month:

- Plant shade trees, fruit trees, and evergreen shrubs.

- Do major re-shaping of shade trees, if needed, during the winter dormancy.

- Check houseplants for insect pests such as scale, mealy bugs, fungus gnats, whitefly and spider mites.

- Continue to mulch leaves from the lawn. Shred excess leaves and add to planting beds or compost pile.

- Replenish finished compost and mulch in planting beds, preferably before the first freeze.

- Switch sprinkler systems to ‘Manual’ mode for the balance of winter.

- Water thoroughly before a hard freeze to reduce plants’ chances of damage.

- Water lawn and all other plants once every three weeks or so, if supplemental rainfall is less than one inch in a three week period.

- Fertilize pansies and other winter annuals as needed.

- Build protective coverings or moving devices for tender plants before the freeze warming.

- Be sure to clean, sharpen and repair all your garden and lawn tools. Now is also the best time to clean and have your power mower, edger and trimmer serviced.

- Be sure the mower blade is sharpened and balanced as well.

- Provide food and water to the area’s wintering birds.

Mowing a lawn. Photo Credit: University of Florida/IFAS

by Joshua Criss | Oct 4, 2024

Winter color is not always easy to find here in Florida. While staple annuals such as snapdragons (Antirrhinum majus) require planning and extra effort in the autumn. Instead, envision a perennial powerhouse that will not only provide colorful berries when the temperature drops but is a pollinator magnet in the spring. The Holly tree (Ilex spp.) perfectly embodies this vision. These low-maintenance evergreens, with their waxy leaves and colorful berries, are a sight to behold in your landscape, whether as a hedge or an accent plant.

Where and How to Plant

Hollies generally prefer partial shade and well-drained soils. However, exceptions exist, such as the Dahoon holly (Ilex cassine), adapted to wetter environments. Whatever cultivar you place in your landscape, following the planting and care instructions is crucial. Plant it in a hole approximately one foot wider than the root ball. Dig deep enough to cover most of the root ball but shallow enough so the uppermost root is slightly above the soil line. This may be counterintuitive, but roots need air to thrive, and shallow planting allows infiltration in the rhizosphere. To regulate soil temperature and soil moisture, add a 2-3 inch layer of mulch around the base of the plant. It is critical to leave some space between the tree trunk and mulch.

Photo: Edward Gilman, UF/IFAS.

Cultural Practices for Success

Irrigation is critical to establishing these plants, which should take between 3 and 6 months. Once established, cease irrigation except in drought conditions. Don’t apply too much water in either case, as hollies will suffer with wet feet. Fertilizers should be applied twice yearly in March and September. Have your soil tested before applying fertilizer to ensure a complete nutrient profile.

Pruning is not routinely required with holly trees. It is advisable to remove dead, diseased, and dysfunctional branches. Dysfunctional branches are those that grow back toward the main leader of the tree. These risk rubbing against one another, causing wounds that may become infiltration sites for pathogens. You should also remove sprouts coming from the root zone, commonly called suckers.

Potential Issues

Pests and pathogens are infrequent in hollies and are usually the product of improper growing practices. Occasionally, scale or spittlebug insects can infest the tree. Their presence will be punctuated by the appearance of blackened leaves, which is a symptom of sooty mold. Scouting these plants often will allow early detection and control of these pests. Some pathogens may also affect these trees. Most often, these are fungi caused by excessive moisture. Look for dieback or strange growth patterns in the plant’s foliage. When you see these, make sure the roots are not waterlogged.

Photo: UF/IFAS

Summing Things Up

Hollies are an excellent and low maintenance addition to any landscape. Their berries and flowering patterns provide multiple seasons of interest and are a resource for birds and pollinators alike. For more information on Florida wildflowers, see these Ask IFAS documents, or contact your local extension agent for additional information on this and any topic regarding your gardens and more.

by Sheila Dunning | Sep 30, 2024

Looking to add something to brighten your landscape this autumn? Firespike (Odontonema strictum) is a prolific fall bloomer with red tubular flowers that are very popular with hummingbirds and butterflies. It’s glossy dark green leaves make an attractive large plant that will grow quite well in dense shade to partial sunlight. In frost-free areas, firespike grows as an evergreen semi-woody shrub, spreads by underground sprouts and enlarges to form a thicket.

Bright red blooms of Firespike

In zones 8 and 9 it usually dies back to the ground in winter and resprouts in spring, producing strikingly beautiful 9-12 inch panicles of crimson flowers beginning at the end of summer and lasting into the winter each year. Firespike is native to open, semi-forested areas of Central America. It has escaped cultivation and become established in disturbed hammocks throughout peninsular Florida, but hasn’t presented an invasive problem. Here in the panhandle, firespike will remain a tender perennial for most locations. It can be grown on a wide range of moderately fertile, sandy soils and is quite drought tolerant. Firespike may be best utilized in the landscape in a mass planting. Plants can be spaced about 2 feet apart to fill in the area quickly. It is one of only a few flowering plants that give good, red color in a partially shaded site. The lovely flowers make firespike an excellent candidate for the cutting garden and is a “must-have” for southern butterfly and hummingbird gardens. Additional plants can be propagated from firespike by division or cuttings. However, white-tailed deer love firespike too, and will eat the leaves, so be prepared to fence it off from “Bambi”.