by Carrie Stevenson | Oct 28, 2021

Coastal plain honeycombhead blooms through the summer and early fall on local beaches. Photo credit, Bob Pitts, National Park Service

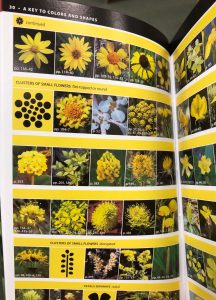

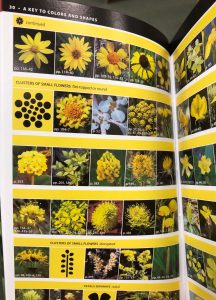

Over my years of leading people on interpretive trail hikes, I have learned it is particularly important to know the names of the plants that are in bloom. These flowers are eye-catching, and inevitably someone will ask what they are. In fact, one of my favorite wildflower identification books is categorized not by taxonomy, but by bloom color—with a rainbow of tabs down the edge of the book for easy identification.

Wildflower identification can be tough, but color-coded guidebooks are really helpful! Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

In our coastal dunes right now, several plants are showing off vibrant yellow blooms. Seaside goldenrod, coreopsis, and other asters are common. Rarer, and the subject of today’s post, is the Coastal Plain Honeycombhead (Balduina angustifolia). It has bright yellow flowers, but often gets more notice due to its unusual appearance when not in bloom. The basal leaves are bright green and similar in shape and arrangement to a pine cone or bottlebrush (albeit a tiny one), sticking straight up in the sand. The plants are typically found on the more protected back side of primary dunes or further into secondary dunes, a little more inland from the Gulf.

When not in bloom, the plant resembles a green pinecone planted in the sand. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

The plant plays a special role in beach ecology, as a host plant for Gulf fritillary butterflies and the Gulf Coast solitary bee (Hesperapis oraria). The bee is a ground-dwelling pollinator insect that forages only in the barrier islands of Mississippi, Alabama, and Florida. The species is currently the subject of a University of Florida study, as the endemic bee’s sole source of nectar and pollen is the honeycombhead flower. As of publication date, no bee nests have been discovered. Researchers are interested in learning more about the insect’s life cycle and nesting behaviors to better understand and protect its use of local habitats. Based on closely related species, it is believed the Gulf Coast solitary bee builds a multi-chambered nest under the soft sands of the dunes.

Adult female Hesperapis oraria foraging on coastal plain honeycombhead (Balduina angustifolia). Photograph by John Bente, Florida Department of Environmental Protection, Florida Park Service.

While the honeycombhead plant is found in peninsular Florida and coastal Georgia, the bee has been identified only in a 100 km² area between Horn Island, MS, and St. Andrews Bay, FL. Luckily for the bee, large swaths of this land are preserved as part of Gulf Islands National Seashore and several state parks. Nonetheless, these coastal dune habitats are threatened by hurricanes, sea level rise, and development (outside the park boundaries). Due to its rarity and limited habitat, a petition has been submitted to the Fish and Wildlife Service for protection under the Endangered Species Act.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 30, 2021

False Foxglove in a Calhoun County natural area. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Fall is the absolute best season for wildflower watching in the Panhandle! When mid-September rolls around and the long days of summer finally shorten, giving way to drier air and cooler nights, northwest Florida experiences a wildflower color explosion. From the brilliant yellow of Swamp Sunflower and Goldenrod, to the soothing blue of Mistflower, and the white-on-gold of Spanish Needles, there is no shortage of sights to see from now until frost. But, in my opinion, the star of the fall show is the currently flowering False Foxglove (Agalinus spp.).

Named for the appearance of their brilliant pink flowers, which bear a resemblance to the northern favorite Foxglove (Digitalis spp.), “False Foxglove” is actually the common name of several closely related species of parasitic plants in the genus Agalinus that are difficult to distinguish by all but the keenest of botanists. Regardless of which species you may see, False Foxglove is an unusual and important Florida native plant. Emerging from seed each spring in the Panhandle, plants grow quickly through the summer to a mature height of 3-5’. During this time, False Foxglove is about as inconspicuous a plant as grows. Consisting of a wispy thin woody stem with very small, narrow leaves, plants remain hidden in the flatwoods and sand hill landscapes that they inhabit. However, when those aforementioned shorter September days arrive, False Foxglove explodes into flower sporting sprays of dozens of light purple to pink tubular-shaped flowers that remain until frost ends the season.

False Foxglove flowering in a Calhoun County natural area. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

In addition to being unmatched in flower, False Foxglove also plays several important ecological roles in Florida’s natural areas. First, False Foxglove’s relatively large, tubular-shaped flowers are the preferred nectar sources for the larger-sized native solitary and bumble bees present in the Panhandle, though all manner of generalist bees and butterflies will also visit for a quick sip. Second, False Foxglove is the primary host plant for the unique Common Buckeye butterfly. One of the most easily recognizable butterflies due to the large “eye” spots on their wings, Common Buckeye larvae (caterpillars), feed on False Foxglove foliage during the summer before emerging as adults and adding to the fall spectacle. Finally, False Foxglove is an important indicator of a healthy native ecosystem. As a parasitic plant, False Foxglove obtains nutrients and energy by photosynthesis AND by using specialized roots to tap into the roots of nearby suitable hosts (native grasses and other plants). As both False Foxglove and its parasitic host plants prefer to grow in the sunny, fire-exposed pine flatwoods and sand ridges that characterized pre-settlement Florida, you can be fairly confident that if you see a natural area with an abundance of False Foxglove in flower, that spot is in good ecological shape!

The Florida Panhandle is nearly unmatched in its fall wildflower diversity and False Foxglove plays a critical part in the show. From its stunning flowers to its important ecological roles, one would be hard-pressed to find a more unique native wildflower! For more information about False Foxglove and other Florida native wildflowers, contact your local UF/IFAS County Extension office.

by Pat Williams | Sep 9, 2021

As homeowners, we do value our trees and no one wants to lose a shade tree especially on the house’s south side in Florida. On a recent site visit, a hickory tree had multiple concerns. Upon closer inspection, the tree had a bacterial infection about 30” off the ground with a smelly, black-brown ooze seeping forth. The leaf canopy was riddled with beetle holes and leaf margins were chewed by caterpillars. When leaves were viewed under the microscope, thrips (insects) and spider mites were found running around. The biggest homeowner cosmetic concern arose from hickory anthracnose (fungus) and upon closer inspection found the leaves to have hickory midge fly galls. The obvious question is should the tree come down? I’ll have you read the whole article before giving you the answer.

Each hickory gall is approximately 3/16″ wide.

Hickory anthracnose or leaf spot as seen in the banner photo is caused by a fungal infection during the wet summer months in Florida. The homeowner can usually recognize the disease by the large reddish brown spots on the upper leaf surface (sending a sample to the NFREC Plant Pathology Lab will confirm the diagnosis) and brownish spots with no formal shape on the bottom. Be sure to rake and remove all leaves to prevent your disease from overwintering close to the tree thus reducing infection next year.

A hickory gall has been cut in half to show the leaf tissue.

The fungus can be lessened by good cultural practices and appropriate fungicidal applications. Please remember it is best left to professionals when spraying a large tree. This alone is not cause to remove your tree.

Hickory gall is caused by the hickory midge fly, an insect that lays eggs in the leaf tissue. The plant responds by building up tissue around each egg almost like the oyster when forming a pearl.

As the gall tissue grows, eggs hatch and larva start to feed on this tissue. The larva will continue to

The larva has eaten all soft material inside the gall and is ready to pupate.

feed until it is ready to pupate within the gall. After forming a pupa, the midge fly will eventually emerge as an adult and females will continue to lay eggs on other leaves. The galls are more of a cosmetic damage and because your hickory leaves will fall from the tree as winter comes, the galls will normally not cause enough damage to worry about each year. Once again good cultural practices and disposal of each year’s leaves will reduce the gall numbers next year.

In a large tree with many leaves, foliar feeding by beetles and caterpillars do cause damage though the leaves will still produce enough food (photosynthesis) to keep the tree alive. Most of us never climb our trees to look at leaves to see the small insects/mites and there are more than enough leaves to maintain tree health.

The biggest concern during my site visit was their tree’s bacterial infection. A knife blade was pushed into the wound area and went in less than 1/4″. The homeowner was instructed to look at bactericide applications. In the end, this hickory tree with so many problems is still shading the home and helping cool the house. It is still giving refuge to wildlife and beneficial insects. When in doubt give our trees the benefit and keep them in place. Remember your local Extension agent is set up to make site visits and saving a tree is time well spent.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Sep 9, 2021

Bulbs are my favorite class of ornamental plants. They generally are low maintenance, come back reliably year after year, and sport the showiest flowers around. While many bulbs like Daylily, Crinum and Amaryllis are very common in Panhandle landscapes, there is a lesser-known genus of bulbs that is well worth your time and garden space, the Rainlily (Zephyranthes spp.).

Rainlily, aptly named for its habit of blooming shortly after summer rainfall events and a member of the Amaryllis family of bulbs, is a perfect little plant for Panhandle yards for several reasons. The plant’s genus name, Zephyranthes – which translates to English as “flowers of the western winds”, hints at the beauty awaiting those who plant this lovely little bulb. From late spring until the frosts of fall, Rainlily rewards gardeners with flushes of trumpet-shaped flowers in shades of white, pink, and yellow, with some hybrids offering even more exotic colors. While these individual flowers typically only persist for a day or two, they are produced in “flushes” that last several days, extending the show. Though Rainlily flowers are the main event for the genus, beneath the blooms, plants also offer attractive, grass-like, evergreen foliage. These aesthetic attributes lend themselves to Rainlily being used in a variety of ways in landscapes, from massing for summer color ala Daylilies, to use around the edges of beds as a showy border like Liriope or other “border” type grassy plants.

Unknown Rainlily species blooming in a raised bed. Photo courtesy of Daniel Leonard.

Continuing along the list of Rainlily attributes, the genus doesn’t require much in the way of care from gardeners either. Most species of Rainlily, including the Florida native Z. atamasca, have no serious pests and are right at home in full sun to part shade. Once established, plants are exceedingly low-maintenance and won’t require any supplemental irrigation or fertilizer! Some Rainlily species like Z. candida even make excellent water or ditch garden plants, preferring to have their feet wet most of the year – putting them right at home in the Panhandle this year. And finally, all Zephyranthes spp. do very well in containers and raised beds also, adding versatility to their use in your landscape!

The one drawback of Rainlily is that they can be somewhat difficult to find for sale. As these bulbs are an uncommon sight in most garden centers, to source a specific Zephyranthes species or cultivar, one is probably going to need to purchase from a specialty internet or mail-order nursery. As with other passalong-type bulbs though, the absolute best and most rewarding way to obtain Rainlily is to get a dormant season bulb division from a friend or fellow gardener who grows them. There are many excellent unnamed or forgotten Zephyranthes cultivars and seedlings flourishing in gardens across the South, waiting to be passed around to the next generation of folks who will appreciate them!

Even if you must go to some lengths to get a Rainlily in your garden, I highly recommend doing so! You’ll be rewarded with years of low-maintenance summer color after the dreariest of rainy days and will be able to pass these “flowers of the western wind” on to the next gardening generation. For more information on growing, sourcing, or propagating Rainlilies, check out this EDIS publication by Dr. Gary Knox of the UF/IFAS North Florida Research and Education Center (NFREC) or contact your local UF/IFAS Extension office! Happy Gardening!

by Carrie Stevenson | Aug 5, 2021

The moon-like eyespots and long tails on its wings are identifying features of the luna moth. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

We hear about butterflies all the time–their beautiful wing patterns, how to plant entire gardens for them, and the fascinating migration patterns of monarchs. But if you look around, you might just find their night-dwelling cousins, the moths, have some pretty incredible traits, too.

I find luna moths (Actias luna) just as interesting as many of the colorful butterflies native to our area. Luna moths are considerably larger than the little brown and black moths you see fluttering around streetlights. Their wingspan can be up to 4” wide, with long, tapering tails trailing behind them. The moth is native to the entire eastern portion of the United States, but has a longer life span the further south it resides. Luna moths live year-round in Florida, with up to three generations (trivoltine) born annually. They are pale green, and adults have a furry white underbelly. Lunas are so eye-catching that they have been featured on the cover of a field guide to moths, postage stamps from the United States and other countries, and as the mascot of the insomnia medication, Lunesta.

The caterpillar of the luna moth is bright green and warns off predators by making an intimidating clicking sound. Photo credit: University of Florida

Luna moths have several celestial ties in their name. All the moths in its larger family, Saturnidae, have round eyespots (which fool would-be predators) composed of concentric circles like the rings of Saturn. “Luna” comes from the Latin for moon, after the moon-colored eyespots on its back.

Luna moth caterpillars are fat and green—the classic caterpillar—and about 2.5” long. Their preferred host plants in the south are typically sweet gum, hickory, walnut, and persimmon trees. Interestingly, the caterpillars can make a sound, typically described as a clicking noise. Biologists believe this noise-making is a defense mechanism, performed as a precursor to spitting up unpleasant fluids to fend off predators. Several studies have shown that the twisting motion of the adult luna moth’s long tails in flight can interrupt the echolocation of bats, helping the moths evade predation.