by Carrie Stevenson | Apr 30, 2020

White-topped pitcher plants in bloom at Tarkiln State Preserve. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

If you live in northwest Florida or southeast Alabama and have never laid eyes on our wild native carnivorous plants, it is about time! April and early May are the best times to see them in bloom. We have six species of pitcher plants (Sarracenia), the most common being the white-topped (Sarracenia leucophylla). However, they come in multiple colors, from yellow and red to a deep purple, and in different sizes.

One thing they all have in common, though—they eat meat. Carnivorous plants all over the world have evolved in places that left them few other options for survival. These plants are typically found in extremely wet, acidic, mucky soils with very low nutrient levels. Normally, plants uptake nutrients like nitrogen and phosphorus from the soil around them. Not being available in these particular environments, carnivorous plants (or more specifically, insectivorous) developed a way to extract nutrients from insects.

Small parrot pitcher plants lie on the ground instead of standing upright at Blackwater State Forest. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

So how does it work? Pitcher plants have a modified leaf, which instead of lying out flat like most plants, is rolled up into a tube, or “pitcher” shape. The inside of the pitcher has a sweet sap, and the walls of the tube are lined with tiny, downward-pointing hairs. Separate from the leaf, the plant has an elaborate flower structure, which attracts insects for pollination. While nearby, these insects are also attracted to the colorful leaf and the sweet sap in its pitcher. The insect will land on the lip of the leaf, then crawl down.

A lizard waits patiently a the bottom of a pitcher plant, hoping to catch insect prey. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Those sticky, downward facing hairs are a trap, preventing insects from leaving the pitcher. Enzymes—a cocktail of proteins naturally found in many other plants but used creatively here—in the sap break down the bug bodies and convert them to nutrients for the plant. In fact, if you slice a cross-section into a pitcher wall or break open a dried one, you will see countless dried exoskeletons at the bottom of the tube. Several other enterprising species have taken advantage of the pitcher plant’s creative structure. More than once, I have seen tiny spiders spin webs across the mouth of the tube, or small lizards and frogs at the bottom, waiting patiently for prey.

Some of the best places to see pitcher plants in the area—they also bloom in October—are Tarkiln Bayou State Preserve, Weeks Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve, Splinter Hill Bog Preserve, and Blackwater State Forest.

by Mark Tancig | Apr 30, 2020

Symptoms of oak leaf blister on swamp chestnut oak. Credit: Gordon Magill.

Even during global pandemics, it’s a joy to be outside during the great north Florida spring we’ve been experiencing lately. As cold fronts come through with their rain bands, some packing a punch, they leave behind the most pleasant mornings, clear blue daytime skies, and crisp evenings. Unfortunately, we’re not the only organism that also enjoys those cool days. Many species of fungi are quite active this type of year as the rains, followed by warmer, yet not too hot temperatures, create the perfect conditions for fungal growth. Some of these fungi grow right on or in the plants we’d like to be enjoying for ourselves, stealing nutrients and causing plant decline or merely causing aesthetic damage. As this is an active time for certain species of fungi, local extension offices are getting more calls and questions regarding lawn and landscape damage due to fungal pathogens. A recent call was a new one for me and an example of a native fungi-plant interaction that looks bad but requires no intervention from us. It also highlights how correctly identifying a disease leads to the best action and can often save time and money and prevent unnecessary pesticides (in this case a fungicide) from entering the environment.

Close up of oak leaf blister on swamp chestnut oak. Credit: Gordon Magill.

The fungi and plant involved here was the oak leaf blister (Taphrina caerulescens) on a swamp chestnut oak (Quercus michauxii). It forms, you guessed it, blisters on the leaves of any of the oaks, though live oak (Quercus virginiana), laurel oak (Quercus laurifolia), and water oak (Quercus nigra) seem to be preferred hosts. The spores of the fungi, dormant since the previous summer/fall and which happen to get lodged in bud scales through wind and rain, germinate in cool, wet weather. The fungus then infects young leaves as they flush and its growth causes a disruption in the leaves’ development. This leads to the blistered look of the leaf tissue and, during extended periods of cool, wet weather, the entire leaf sort of shrivels, browns, and eventually falls off. Spores are eventually released from the fallen leaves to start the process over the next spring.

Severe oak leaf blister on swamp chestnut oak. Credit: Gordon Magill.

Though the leaves look pretty terrible, this fungal disease rarely causes plant health issues and the tree recovers just fine. Specimen trees that experience it year to year may be treated with a fungicide, but most homeowners can just let it go. Raking up and disposing of the leaves may help prevent further infections by reducing the number of spores released in the area.

As you enjoy another cool morning after an evening rainstorm, remember that the fungi all around you are also having a great day. You may want to look at your landscape plants and see if there’s anything abnormal going on. If so, take a photo and send it to your local extension office for help with identification and best methods of control, or, like in this case, just leaving it alone.

p.s. As I said this was a new one for me and I want to thank Stan Rosenthal, Extension Agent emeritus, for assisting with identification.

by Carrie Stevenson | Apr 15, 2020

The sight and scent of a wild azalea blooming in the woods can stop you in your tracks! Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

From a distance, native azaleas are easily mistaken for honeysuckle vines. With long, arching stamens, you might be tempted to relive your childhood, hoping to pull the pistil from the bottom and find a single drop of sweetness on the end. Instead, upon close observation you will encounter an equally pleasurable but distinctly different scent. The wild Rhododendron canescens, known variously as a mountain, piedmont, or honeysuckle azalea, can range in flower color from white to deep pink. In northwest Florida, you will find it on the edges of swamps, or as I did on the sunny fringes of wooded areas with rich, moist soil. It is in bloom right now (March), along with its cousins, the white-blooming swamp azalea (Rhododendron viscosum) and the brilliant orange Florida flame azalea (Rhododendron austrinum).

The delicate flower of a honeysuckle azalea attracts hummingbirds and butterflies in the spring. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Native azalea populations have declined due to wetland habitat loss, and their delightful smell and delicate flowers have made them susceptible to overcollection. Due to these factors, the Florida flame azalea is listed on the state endangered species list and wild azaleas should never be removed from their habitat. Native azalea species attract butterflies and hummingbirds, and are often planted in home landscapes as ornamental shrubs. Be sure you purchase them from reputable dealers that are not collecting from the wild.

by Daniel J. Leonard | Apr 8, 2020

There aren’t a lot of quality landscape plant options that fit the description nearly every homeowner desires: native, low-maintenance, slow-growing, pest free, drought tolerant while tolerating wet soils, loving both sun or shade, and green year-round. Needle Palm (Rhapidophyllum hystrix) is the rare plant that checks all those boxes and deserves consideration when adding plants to your landscape!

6 year old Needle Palm in a local landscape. Photo courtesy the author

Needle Palm is an endangered native, growing in a narrow range in the coastal Southeastern US, Calhoun and Liberty counties included. It is primarily found in the understories of wet wooded areas along slopes, ravines, and bottoms; if you’ve ever hiked the Apalachicola Ravines or Torreya State Park trails, you’ve likely encountered Needle Palm in the wild! Being native is nice, but what makes Needle Palm an outstanding landscape option?

Needle Palm is the prettier, more refined cousin of Saw Palmetto (Serenoa repens), which it is sometimes confused with. Unlike the rambling, aggressive, stiff-leaved palmetto, Needle palm possesses “softer”, finely cut, lustrous evergreen leaves, allowing it to add amazing texture to any landscape. Also, unlike palmetto, it doesn’t need a yearly “cleaning” to prune out brown, dead leaves, rather its leaves persist green and clean for many years! You might not want to reach into the interior of a Needle Palm plant anyway, as generally unseen 6-8” namesake “needles” surround the base of its trunk. Needle Palm grows very slowly, eventually reaching 8’ tall or so, but is more often seen in the 4-6’ range in landscapes. This is absolutely a shrub that will never outgrow its welcome. It is a nearly trunkless palm, almost always appearing as a shrub, though with extreme old age it can begin to look a bit like a small tree with a muted trunk. With outstanding aesthetics and a low-maintenance growth habit, Needle Palm has a place in nearly any landscape.

Mature needle palm, 6′ tall and wide. Photo courtesy the author.

In the landscape, Needle Palm does best when sited with some shade in the afternoon but also thrives in full sun. They appreciate regular water during establishment but survive on their own without any extra irrigation after! Needle Palm also doesn’t need much in the way of supplemental fertilization. They do look their best with a light spring application of a general purpose, slow-release fertilizer, but this is not required. Needle Palms are not afflicted with the pest and pathogen problems the much more commonly used non-native Sago Palms (Cycas revlolutas) attracts. I’ve grown Needle Palm for 6 years in the landscape and have never noticed any pest or disease issues. With Needle Palms becoming more common in the nursery trade, I don’t see a place in most landscapes for the inferior, high-maintenance, insect infested Sagos. If you want the tropical, textured look of Sagos, plant Needle Palm instead.

Needle Palm is an extremely attractive, low-maintenance Northwest Florida native plant that you should absolutely seek out and add to your landscape! If you want more information or have any questions about Needle Palm or any other landscape/garden topic, please give your local UF/IFAS County Extension Office a call. Happy Gardening!

by Daniel J. Leonard | Nov 21, 2018

After a devastating windstorm, as we just experienced in the Panhandle with Hurricane Michael, people have a tendency to become unenamored with landscape trees. It is easy to see why when homes are halved by massive, broken pine trees; pecan trunks have split and splayed, covering entire lawns; wide-spreading elms were entirely uprooted, leaving a crater in the yard. However, in these times, I would caution you not to rush to judgement, cut and remove all trees from your landscape. On the contrary, I’d encourage you, once the cleanup is over and damaged trees rehabilitated or disposed of, to get out and replant your landscape with quality, wind-resistant trees.

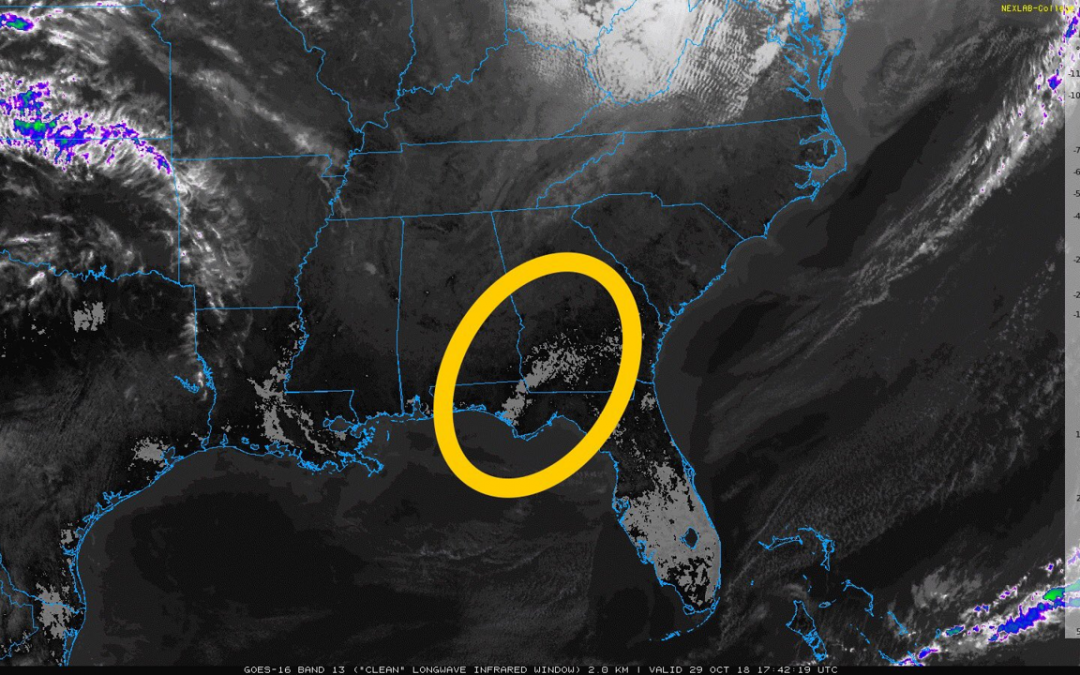

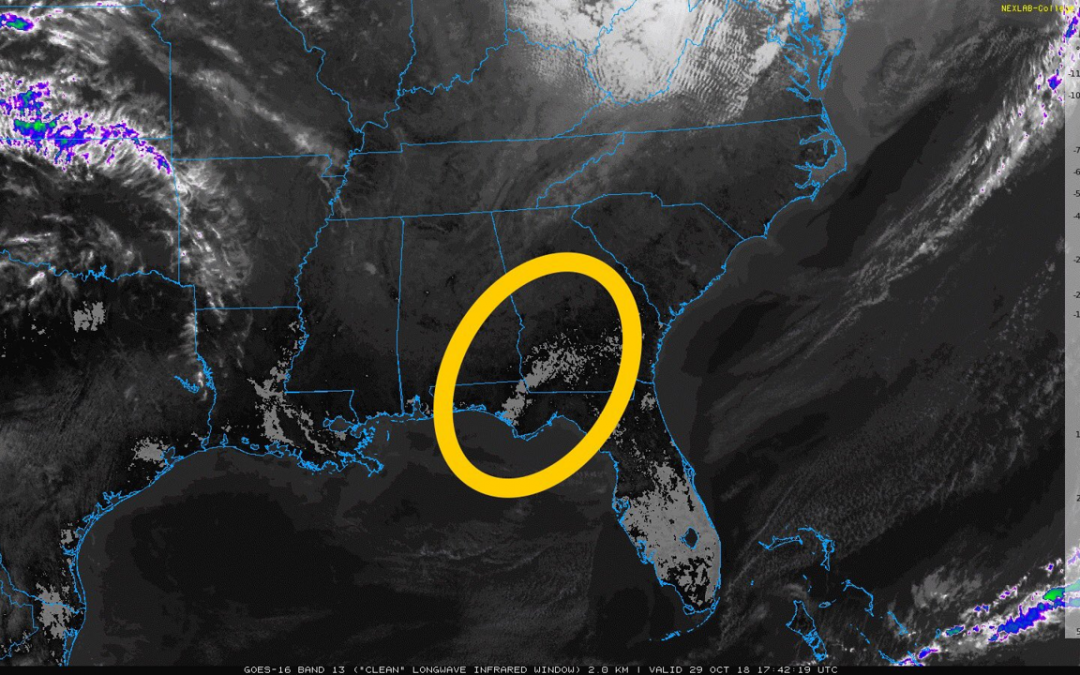

First, it’s helpful to take a step back and remember why we plant and enjoy trees and the important role they play in our lives. Beyond the commercial aspect of farmed timber, there are many reasons to be judicious with the chainsaw in the landscape and to plant anew where seemingly sturdy trees once stood. For example, trees provide enormous service to homes and landscapes, from massive cooling effects to aesthetic appeal. Take this thermal satellite image of Hurricane Michael’s path that simultaneously shows the devastation of a major hurricane and the role trees play in the environment.

Lightly shaded area showing higher ground temperatures from loss of vegetation.

In the lighter colored areas where the wind was strongest and catastrophic tree damage occurred, the ground temperatures are much higher than the unaffected areas. Lack of plant life is entirely to blame. Plants, especially trees, provide enormous shading effects on the ground that moderate ground temperatures and the process of transpiration releases water vapor, cooling the ambient air. Trees also lend natural beauty to neighborhood settings. There is a reason people termed the hardest hit areas by Michael “hellscapes”, “warzones”, etc. Those descriptions imply a lack of vegetation due to harsh conditions. In this respect, trees soften the landscape with their foliage colors and textures, create architecture with their height and shape, and screen people from noise, unpleasant sights and harsh heat.

Though all trees give us the benefits outlined above, research conducted by the University of Florida over a span of ten major hurricanes, from Andrew to Katrina, shows that some trees are far more resistant to wind than others and fare much better in hurricanes. In North Florida, the trees that most consistently survived hurricanes with the least amount of structural damage were Live Oaks, Cypresses, Crape Myrtle, American Holly, Southern Magnolia, Red Maple, Black Gum, Sycamore, Cabbage Palm and a smattering of small landscape trees like Dogwood, Fringe Tree, Persimmons, and Vitex. If one thinks about these trees’ growth habits, broad resistance to disease/decay, and native range, that they are storm survivors comes as no surprise. Consider Live Oak. This species originated along the coastal plain of the Southeastern United States and have endured hurricanes here for several millennia. Possessing unusually strong wood, they have also developed the ability to shed the majority of their leaves at the onset of storms. This defense mechanism leaves a bare appearance in the aftermath but allows the tree to mostly avoid the “umbrella” effect other wide crowned trees experience during storms and retain the ability to bounce back quickly. Consider another resistant species, Bald Cypress. In addition to having a strong, straight trunk and dense root system, the leaves of Bald Cypress are fine and featherlike. This leaf structure prevents wind from catching in the crown. Each of the other listed species possess similar unique features that allow them to survive hurricanes and recover much more quickly than other, less adapted species.

Laurel Oak split from weak branching structure.

However, many widely grown native trees and exotic species simply do not hold up well in tropical cyclones and other wind events. Pine species, despite being native to the Coastal South, are very susceptible to storm damage. The combination of high winds and beating rains loosens the soil around roots, adds tremendous water weight to the crown high off the ground, and puts the long, slender trunks under immense pressure. That combination proves deadly during a major hurricane as trees either uproot or break at weak points along the trunk. In addition to pines, other widely grown native species (such as Pecan, Laurel Oak and Water Oak) and exotic species (such as Chinese Elm) perform poorly in storms. Just as the trees that survive storms well possess similar features, so do these poor performers. We’ve already mentioned why pines and hurricanes don’t mix well. Pecan, Laurel Oak, and Water Oak tend to have weak branch angles and break up structurally in wind events. The broad spreading, heavy canopy of trees like Chinese Elm cause them to uproot and topple over. It would be advisable when replanting the landscape, to steer clear of these species or at least site them a good distance from important structures.

This piece is not a warning to condemn planting trees in the landscape; rather it is a template to guide you when selecting trees to replant. Many of our deepest memories involve trees, whether you first climbed one in your grandparent’s yard, fished under one around a farm pond, or carved your initials into one in the forest. Don’t become frustrated after a once in a lifetime storm and refuse to replant your landscape or your forest and deprive your children of those experiences. As sage investor Warren Buffett once wisely said, “Someone is sitting in the shade today because someone planted a tree a long time ago.”

For these and other recommendations about how to “hurricane-proof” your landscape, contact your local UF/IFAS Extension Office. Plant a tree today.