by Laura Tiu | Nov 18, 2016

Snorkeler at Morrison Springs – Laura Tiu

Morrison Springs Bald Cypress

There are over 1000 springs identified in Florida. In the Panhandle, the majority of the springs are karst or artesian springs rising deep from the Floridan Aquafer System within the states limestone base. Springs are unique and can be identified by perennial flows, constant water temperature and chemistry, high light transparency. This yields a freshwater ecology dependent on these features. Springs are classified based upon the average discharge of water but can exhibit a lot of variability based on water withdrawals and rainfall. These springs are some of our most precious water resources, supplying the drinking water our communities rely on, as well as providing great recreation opportunities.

Morrison Springs is a popular spring in northwest Florida and is one of 13 springs flowing into the Choctawhatchee River Basin. It is a large, sandy-bottomed spring surrounded by old growth cypress. The spring pool is 250 feet in diameter, discharges an average of 48 million gallons of water each day from three vents into the Choctawhatchee River as a second magnitude spring. The spring contains an extensive underwater cave system with three cavities up to 300 feet deep and is popular for scuba diving, swimming and snorkeling, kayaking, canoeing and fishing. Historically, it was privately owned and was a popular swimming hole for locals. In 2004, the state of Florida purchased the land containing the spring in the Choctawhatchee River floodplain. The land was leased to Walton County for 99 years. The county created a 161-acre park with a picnic pavilion, restroom facilities and a wheelchair-accessible boardwalk. A down-stream boat ramp provides access to the river away from swimmers and divers. There is no entrance fee.

Morrison Spring is filled with abundant fish and plant life. Fish include largemouth bass, spotted bass, hybrid striped bass, bluegill, sunfish, redbreast sunfish, warmouth, black crappie, striped bass, catfish, alligator gar, bowfin, carp, mullet and flounder or hogchoakers (freshwater sole). It is also home to some nocturnal freshwater eels that swim around the vent and delight the divers. Most are gray, about an inch in diameter and maybe a foot or two long. The spring supports many trees, plants, and grasses including bald cypress, live oak, red maple, pawpaw, red and black titi, Cherokee bean, sweetbay, blackgum, juniper, red cedar, southern magnolia, laurel oak, tupelo, hickory, willow, wax myrtle, cabbage palm, saw palmetto blueberry, hydrangea, St. John’s wort, mountain laurel, water lily, pickerelweed, pitcher plant, broad leaved arrowhead, fern, and moss.

Morrison Springs was previously considered one of the cleanest springs in Florida until 2010 (Florida Springs Initiative). All of Florida springs are currently at risk as the state population continues to increase. Spring flows are decreasing as the result of increasing extraction of groundwater for human uses. Development, and the resultant over pumping, and nitrogen pollution from agriculture both have impacts on the aquifer recharge areas. Existing groundwater pumping rates from the Floridan Aquifer in 2010 were more than 30% of average aquifer recharge (Florida Spring Initiative). The University of Florida IFAS Extension Agents in the Panhandle occasionally conduct interpretive guided tours of the Springs to help citizens understand the importance of protecting this unique water source.

by Jennifer Bearden | Nov 18, 2016

Freshly processed venison. Photo credit: Jennifer Bearden

When hunting, food safety begins in the field. The goal is to have safe meat for you and your family to eat. Here are a few ways to keep your food safe:

- Shot placement – that’s right. Food safety begins with an accurate shot. Your goal should be to prevent the contents of the digestive tract from touching the meat. A gut shot can quickly ruin meat and make cleaning the animal harder.

- The quicker you get the meat chilled the better. Improper temperature is meat’s number one enemy. The recommended storage temperature to prevent bacterial growth is 35-40°F.

- Handle the knife with one hand and the carcass with the other. The hide can harbor dirt and pathogens so care should be taken to prevent contamination of the meat.

- Have vinegar water and chlorine water on hand. Vinegar water (50/50) can be sprayed on areas where hair or hide touch the meat. Rinse hands and tools periodically in a bucket of sanitizing solution of 1 tbsp of chlorine per gallon of water.

- Think food safety through the whole process. Prevent cross contamination by keeping anything from contacting the meat unless it has been sterilized. Keep the digestive tract intact and prevent the contents of it from contacting the meat. Chill the meat as quickly as possible. When further processing, continue to use sterile surfaces and tools.

Many hunters age deer meat to increase tenderness and improve flavor. This is safe if done properly. There are two ways to safely age meat. Dry aging in a walk-in cooler or refrigerator is the best but not feasible for all hunters. The walk-in cooler or refrigerator must be clean and have good air circulation and proper temperature control (34-38°F). The meat can aged for 7-21 days depending on the amount of moisture in the cooler. Too much moisture can increase microbial growth on the meat which should be cut away before further processing. There will also be a layer of dry meat that will need to be cut away.

An ice chest can also be safely used to age meat. First, fill the clean ice chest with ice and water. Add meat immediately to ice water and soak for 12-24 hours. This will quickly cool the meat to the proper temperature. Then drain the water out of the cooler and add more ice. Keep cooler drained of water and full of ice for 5-7 days. There may be “freezer burn” on the outside of the meat that can be cut away before further processing.

Remember food safety when further processing and storing. Wild game food safety begins in the field and ends with consumption.

For more information about safe handling of venison:

http://www.noble.org/ag/wildlife/propercareofvenison/

http://www.clemson.edu/extension/hgic/food/food_safety/handling/hgic3516.html

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 18, 2016

I was trying to think of a topic that could connect Thanksgiving and our marine environment. Like many others, when I think of Thanksgiving images of Pilgrims and native Americans come to mind. There is the turkey – and I wrote about “turkey fish” (another name for lionfish) last year. So I continued to think. One thing I do know about the native Americans who lived in this area, they liked oysters. We find middens (piles of oyster shell) in many places around the Gulf coast. These were discard piles from their consumption of the animal. Lots of these indicate, at least to me, that they enjoyed them… and we do also. Oysters are a part of Gulf coast culture and many have them with their Thanksgiving meal.

Oysters are one of the more popular shellfish along the panhandle.

Photo: FreshFromFlorida

Oysters are animals – meaning they lack cell walls and must consume their energy. The food of choice is plankton, sounds good doesn’t it! They possess two tubes called siphons which basically filter seawater. One brings water in, the other expels it. As the water enters their body they filter it for food and oxygen. As it leaves they expel waste and carbon dioxide. At times sand is sucked in and becomes lodged – they cannot expel. This “irritant” is covered by a material called nacre and becomes a pearl. Most are not round nor pretty but occasionally there are nice ones… Pacific oysters make better pearls. Amazingly a single oyster can filter up to 20 gallons of water in a day during the warmer months.

They are invertebrates and belong to the phylum Mollusca – meaning they have a soft body. Many invertebrates have a soft body, but what makes mollusks different is that they have bilateral symmetry (a head and tail end), a coleomic cavity (which allows organ development and increased size), and unique to them is a tissue called a mantle (which can secrete a calcium carbonate shell – and most mollusks do this).

Oysters are in the class Bivalvia – meaning they have two shells connected by a hinge at a point called the umbo. Other bivalves include the clams, scallops, and mussels. All of these are popular seafood products. Oysters differ from other bivalves in that they are cemented to a structure and cannot move around (sessile). Many mussels are sessile also but oysters differ in that they use calcium carbonate to literally cement themselves to the substrate, where mussels use a series of threads to do this. Cementing to the substrate means that they are picky about their habitat – it needs to have a hard substrate, sand will not do. We all know this. Place a piling, clay pot, board, or boat in the water… and oysters find it. Typically, they will attach to each other and form small clumps of oysters. These clumps form larger structures we call oyster reefs (or oyster bars) and this is what the commercial oysterman is looking for – and the recreational boater is trying to avoid!

So how do these oysters, who are sessile, find these habitats? Well, when it is time to reproduce oysters (which are hermaphroditic) release their gametes into the water. The sperm and egg that find each other form a planktonic larva called veliger. To increase the chance of finding each other the oysters release their gametes at the same time – a mass spawn. There are a variety of factors that trigger this but water temperature seems to be an important one. The veliger drift in the currents, developing into juveniles, and then settling out as small oysters called spat. If the currents have brought them to a good location, the spat settle on a hard substrate and the next generation begins. If not, they die. So literally millions of fertilized veliger are produced from individual adults. In many cases the suitable substrate are other oysters.

An oysterman uses his 11 foot long tongs to collect oysters from the bottom of Apalachicola Bay

Photo: Sea Grant

Today oysters seem to be in trouble. Large bars have disappeared due to dredging and over harvesting. Hurricanes certainly do damage to some and poor water quality alters their growth and development. Recently problems in Apalachicola include the lack of river water reaching the Gulf. The higher salinities created by the reduction of river flow have increased the number of oyster predators (starfish and snails) as well as diseases. All of that said, they are still a popular seafood item and enjoyed by many during the holidays. The cooler months mean less bacteria in the water and fewer problems consuming them raw. Cooked oysters have few problems… period.

I hope all have a Happy Thanksgiving and if you have not tried oyster dressing, maybe this year could be the year.

Happy Holidays.

by Mark Mauldin | Nov 7, 2016

A buck chases a doe through plots of wildlife forages being evaluated in 2013 at the University of Florida’s North Florida Research and Education Center. Photo Courtesy of Holly Ober

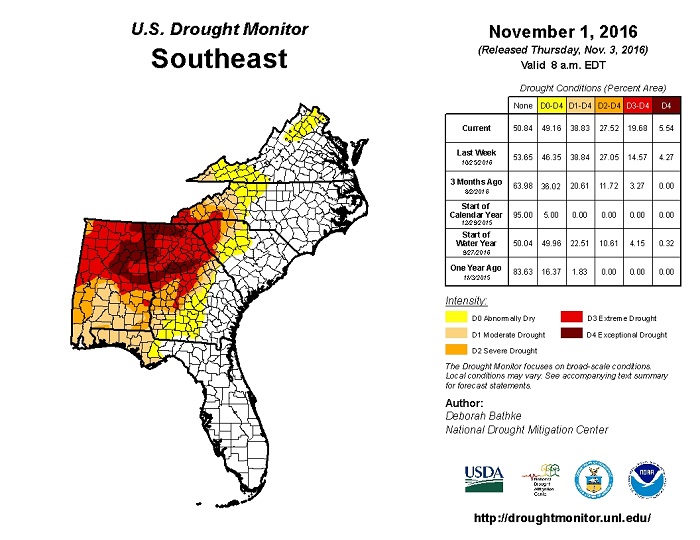

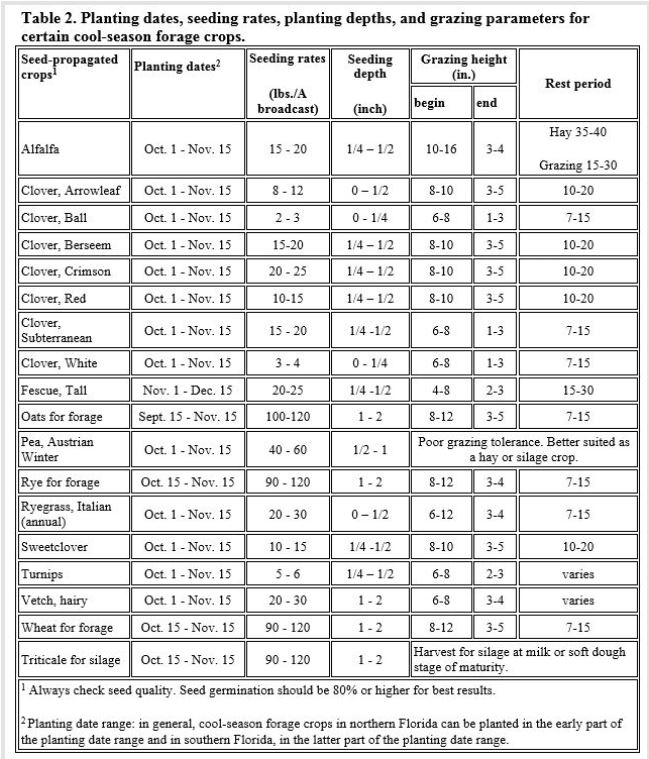

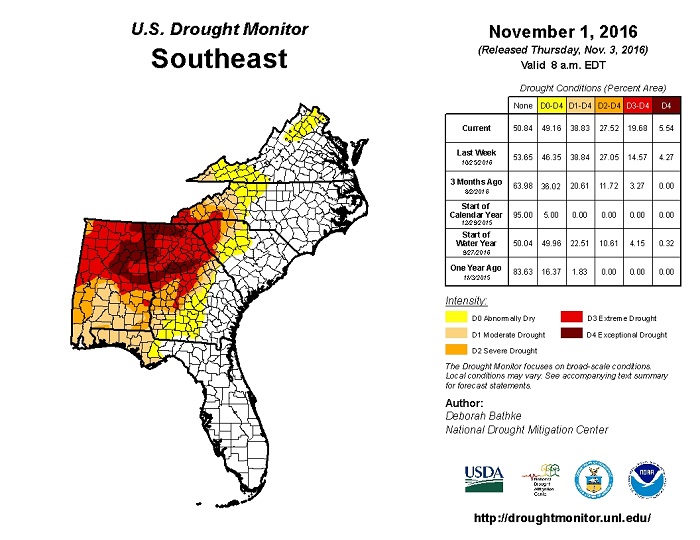

It should be too late in the year for an article about cool season food plots; they should already be up and growing, at the very least planted. It’s November, archery season has begun, the fall food plot ship should have already sailed. However, due to the incredibly dry weather we’ve had for the past several months I hope that ship hasn’t sailed. I hope you have not planted your food plots yet. The tristate area is dry, too dry to plant anything you expect to survive. If you have not already planted, don’t until your area gets substantial rain.

Very dry conditions persist across the Southeast.

The saying goes “The best time to go hunting is whenever I have time”. As the classic weekend-warrior sportsman myself, I can easily relate to that saying and I can also understand how/why folks would apply that same logic to planting food plots. Unfortunately, with this fall’s weather that logic does not hold true. Any plantings made before we have adequate moisture run a very high chance of being complete failures.

These likely failures can playout in a variety of ways but they all end the same. Seedlings have tiny roots systems, moisture must be accessible very near the soil surface in order for them to access it. If moisture is unavailable in the tiny root zone the seedlings will wilt. Wilting greatly diminishes the plants ability to carry out photosynthesis; no photosynthesis no energy. Seedlings have virtually no stored energy to fall back on, so the seedlings begin to die rapidly.

Admittedly, I left out one key detail in the plant horror story above; moisture is required for seed germination. If it is dry enough seeds can be planted and nothing will happen – they won’t germinate, they won’t try to grow, they won’t die from lack of moisture. This fact leads some to conclude, “Plant now and it will come up whenever it rains”. While there is some sound logic in that conclusion, it is a very risky plan when you consider the types of plants we typically include in our wildlife plots. “Dusting in” as it is called in the crop world, can work with larger seeded, deeper planted crops. It is not well suited to small seeded, very shallow planted forages like clover. When a seed is right at the soil surface the tiniest amount of rain or even a heavy dew could provide enough moisture for germination which would likely start the process I described earlier.

The safest bet is to wait until your area has received a good soaking rain and there is a favorable chance for additional rains. As dry as we are now, that first ½ inch shower will not provide adequate moisture for establishment if it is followed by an extended period without additional rain.

Sooner or later it will rain (I think), so you wind up planting your plots later than normal. What does that mean? In the grand scheme of things, not much. As we get later in the year the days get shorter and the air and soil temperatures get lower which can slow the development of the plants. That said, the real growth for most of our cool season forages really occurs in the spring and that will still be that case regardless of if you planted in October, November or December. Remember the goal of food plots should be increasing the quality and quantity of forage available for wildlife throughout the entire year.

The dry weather has messed up food plot establishment as it relates to hunting season but if all you wanted was a game attractant for hunting purposes food plots were probably not your best bet in the first place. It takes considerable time, effort and expense to maintain quality food plots, to the point that they are really not a very practical option if only viewed as an attractant for a few months out of the year.

If attracting deer, not improving habitat, is your primary goal you might consider establishing a feeding station. Be sure to check FWC regulations before you begin feeding game animals.

Be patient, wait for the weather conditions to improve before planting. There is no point in wasting your time and money on plantings that have a very low chance of being successful. Contact your county’s agriculture or natural resources agent for more details relating to the establishment of wildlife plots.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 4, 2016

October 31st not only reminds all that the ghost and goblins are out and about, but that the sea turtle nesting season is complete for another year. These federally protected animals typically begin nesting in late April and continue into the month of October – but there is almost always someone late to the party…

Young loggerhead sea turtle heading for the Gulf of Mexico. Photo: Molly O’Connor

What is neat about sea turtles is that their nesting beaches are usually always in the same general vicinity – meaning Pensacola Beach turtles are Pensacola Beach turtles… each year – and it is always great to see them come back. And this year, come back they did…

I have data collected by Gulf Islands National Seashore going back to 1996. The number of hatching nests on Escambia County beaches has ranged from a low of 8 (2005) to 52 in (2011); it has averaged around 25 hatching nests each year. This year was different…

This year, within the National Seashore, we had a total of 68 nests in Escambia County, 56 of which were on Santa Rosa Island. This is great news!

59 of the 68 nests hatched (87%) – which is also great news – typically only 10-20% of diamond back terrapin nests avoid predators. Most of the sea turtle nests lost this year were due to flooding from tropical storms in the Gulf. There was one nest between Pensacola Beach and Navarre Beach that was raided by a coyote and I am sure there were depredated nests all along the panhandle. But again, between 75-90% of terrapin nests are lost to raccoons, so the sea turtles had a good year. A recent report from southwest Florida states the same – a record nesting season for the Gulf coast.

However, there is still one problem lurking out there… disorientation…

Disorientation occurs when these successful hatchlings emerge from the sand and head the wrong way – typically towards artificial lights. Sea turtles are attracted to shortwave light (blues, greens, and white). Much of our artificial lighting falls into those wavelengths – and attract hatchlings. Since 1996 between 30 – 89% of Escambia County nests have shown signs of disorientation; the average is 49%. This year 63% of the Escambia County nests showed disorientation behavior. We are lucky that we have dedicated turtle watch volunteers to step in and correct these – but they cannot be there for all hatchings – we really need to alter our lighting. Longer wavelengths (yellow and red) do not attract most hatchlings, and therefore – are considered “turtle friendly”. Switching our outdoor lighting to these colors, reducing the illumination, lowering the elevation of the lighting, and shielding the light to direct it towards the ground all help reduce the disorientation problem.

Most panhandle counties have some form of coastal lighting ordinance to address this problem and problems with other wildlife. Ordinances vary some from county to county but the basics are the same; keep it long, keep it low, keep it shielded. Keep it long refers to the wavelength – usually less than 560nm (in the yellow/red portion of the spectrum). Keep low refers the height of the light fixture. If it can be placed at a lower height this is preferred, if not shielding the light source to direct down is required. We must also remember indoor lighting. This can be reduced by simply closing the curtains, moving lamps away from windows, or using tinted windows (if you are replacing yours). Who has to be wildlife friendly varies from county to county, so property owners should contact their Sea Grant Extension Agents if they have questions. There are funds available to help some complete this process and this to varies from county to county.

It’s been a great nesting season, let’s make it even better by reducing the amount of disoriented hatchlings.