Last year I began a series of articles on the Gulf of Mexico. They focused on the physical Gulf – water, currents, and the ocean floor. This year the articles will focus on the life within the Gulf, and there is a lot of it.

Single celled algae are the “grasses of the sea” and provide the base of most marine food chains.

Photo: University of New Hampshire

We will begin with the base of food web systems, the simplest creatures in the sea. The base of food systems are generally plants and the simplest of these are the single celled plants. Singled celled plants are a form of algae, not true plants in the sense we think of them, but serving the same role in the environment – which is the production of much needed energy.

What these single celled algae need to survive is the same as the more commonly known plants – sunlight, water, carbon dioxide, oxygen, and nutrients.

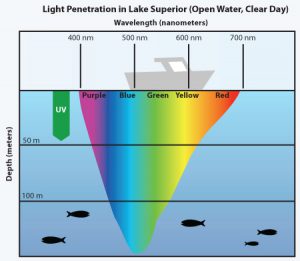

Sunlight is difficult for marine plants because sunlight only penetrates so deep. Therefore, marine plants and algae must live in shallow water, or have some mechanism to remain near the surface in the open sea. In relation to their overall body volume, smaller creatures have more surface area than larger ones. More surface area helps resist sinking and the smallest you can get is a single cell. Thus, most marine algae are single celled. Many single celled plants are encased in transparent shells that have spines and other adaptations to assist in increasing their surface area and keeping them near the surface. Some actually have drops of oil (buoyant in water) making it even easier to stay near the surface. These small floating algae drift in the surface currents, and drifting organisms are called plankton. Plankton that are “plant-like” are called phytoplankton.

The next needed resource is water; the Gulf and Bay are full of it. However, saltwater is not what they need – freshwater is, so they must desalinate the water before absorbing it. They can do this by adjusting the solutes within their cytoplasm. The greater the ratio of surface area is to volume, the more diffusion of solutes can take place – thus these small phytoplankton are very good at diffusing resources in (like water and carbon dioxide) and expelling waste (like ammonia and oxygen).

Carbon dioxide and oxygen are dissolved in seawater and, like water, are diffused into the phytoplankton. Warmer water holds less oxygen so there would be a tendency to have more phytoplankton in colder waters. However, warmer waters are so because there is generally more sunlight, a needed resource. The colder, sunlit, surface waters off some coasts – such as California – have higher amounts of dissolved oxygen and are some of the most productive areas in the ocean. Phytoplankton can also serve as “carbon sinks” by removing carbon dioxide dissolved in the seawater coming from the atmosphere. However, this may not be the answer to excessive CO2 in the atmosphere because, like all creatures, you can only consume so much “food”. Excessive loads of carbon dioxide will not be consumed.

Finally, there is the need for nutrients. All plants need fertilizer. Nutrients in the sea come from either run-off from land, or decayed material from the ocean floor. Much of the nutrients are discharged into the Gulf by run-off from land. Because of this, much of the phytoplankton are congregated nearshore where rivers meet the sea. We think of marine life as equally distributed across the ocean, but in act it is not, there is more life nearshore. For the compost on the ocean floor to be of used by phytoplankton, it must reach the surface. This happens where a current called an upwelling occurs. Upwellings rise from the seafloor bringing with them the nutrients. Where upwellings occur, the seawater is colder, and sunlight abundant, you have the greatest concentration of marine life – all fueled by these phytoplankton.

In the Gulf, one of the most productive places is “the plume”, where the Mississippi River discharges. This massive river brings water, sediments, and nutrients, from most of the continent. The large plankton blooms attract massive schools of plankton consuming fish, predatory fish, sea birds, and marine mammals.

In the next post, we discuss some of the different phytoplankton that inhabit our coastal waters and the amazing things they do.

A satellite image showing the sediment plume of the Mississippi River. This plume brings with it nutrients that fuel plankton blooms.

Image: NASA satellite

References

Kirst G.O. (1996) Osmotic Adjustment in Phytoplankton and MacroAlgae. In: Kiene R.P., Visscher P.T.,

Keller M.D., Kirst G.O. (eds) Biological and Environmental Chemistry of DMSP and Related Sulfonium Compounds. Springer, Boston, MA

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 5 – Reproduction - January 12, 2026

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 4 – Thermoregulation - December 29, 2025

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 3 – Envenomation - December 22, 2025