The definition of an invasive species used by the University of Florida IFAS has three parts.

- It is not native to the area.

- Was brought to the area by humans; either intentionally or accidentally.

- Is causing an environmental or economic problem, or somehow lower the community’s quality of life.

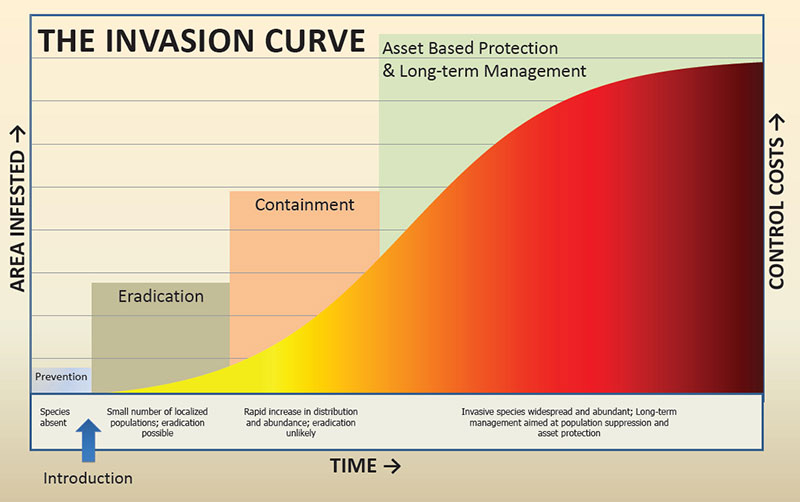

Florida is famous for its invasive species problems. Actually, every state in the country is battling this issue. In 2005 the estimated economic cost of invasive species in the United States was $137 billion annually. Looking at the Invasive Species Curve (below) you can see the most effective method of managing is to prevent them from coming in the first place. Easier said than done. International travel and commerce by plane and boat enters Florida every day, who knows what these are bringing with them. There is the legal trade, illegal trade, and the accidental hitchhiker. Though there are efforts in each state trying to prevent invasive species from entering, they do enter. Once they have arrived, resource managers move into what we call Early Detection Rapid Response (EDRR) in hopes of eradicating the species but at the very least containing them. It is a constant battle.

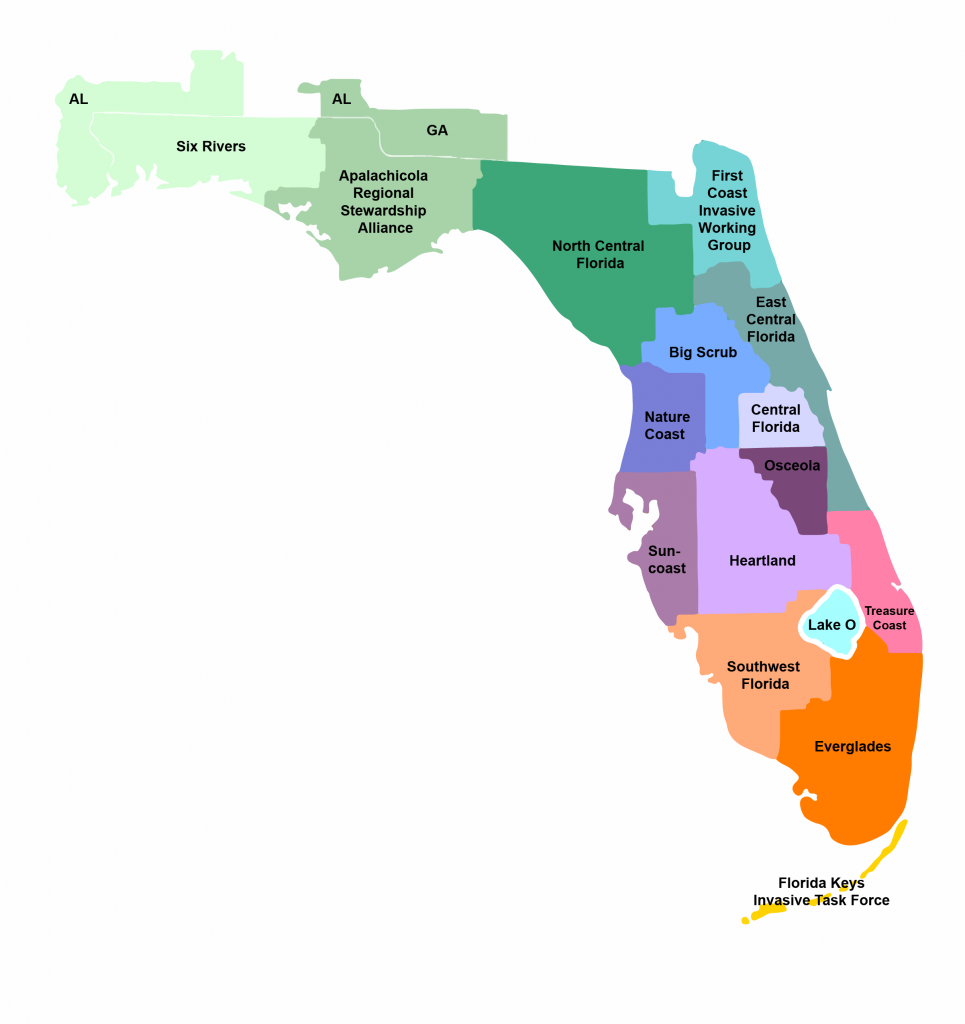

Though separated from the mainland, our barrier islands are not immune to this threat. Humans travel to and from our islands all year round; we live on many of them. With us comes non-native species we both intentionally and accidentally bring. Some of these become invasive and can threated the wildlife of our islands. The state is divided into 15 Cooperative Invasive Species Management Areas (CISMAs). The western panhandle is under the Six Rivers CISMA, the eastern panhandle is under the Apalachicola Regional Steward Alliance (ARSA). Both CISMAs have developed a EDRR list for their area. As a member of the Six Rivers CISMA, I helped developed ours and below are the species considered the biggest threats to our island wildlife.

Beach vitex (Vitex rotundifolia)

Beach vitex is native to the Pacific coast of Asia and was intentionally brought to the United States as an ornamental/landscape plant. It does well in open sunny areas, dry soils, along the coast – perfect for barrier islands. In the 1980s it was used for dune restoration in the Carolinas and that is when its invasive nature was first seen. Like all invasive species, there are few predators and disease, and so reproductive success is high. The species multiples and spreads rapidly, basically uncontrolled. Beach vitex is allelopathic, meaning that it creates an environment that can kill nearby plants and thus take over that area; sea oats are one species this occurs with. Its impact on wildlife could include the loss of required habitat and food source. It appears to have already impacted sea turtle nesting in the Carolina’s, and that threat exist here as well. It could also impact the ecology of the listed beach mouse.

I was first made aware of the presence of this plant in the Pensacola area in 2013. It was discovered on the shoreline of a private property on the Gulf Breeze peninsula in Santa Rosa County. It was suspected to have come from nearby Santa Rosa Island. A survey of the Pensacola Beach area found 22 sites where the plant existed. One was quite large, covering about 70% of the property. The others were small individual plants. Some were part of a homeowner’s landscape; others were on public land. At the time, beach vitex was not listed as an invasive species in Florida. Today it is and has also been declared a state noxious weed. A database search indicates there are currently 118 records in the state of Florida found in six counties. Four of those counties are in the Florida panhandle and include Escambia, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, and Franklin. More in-depth surveys of the coastal areas, and islands, of the remaining counties in the panhandle may find more records of the plant. There are active projects in the Escambia/Santa Rosa area to manage it.

Cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica)

Cogongrass is native to Central and South America. It was brought to the United States accidentally through the Port of Mobile. It quickly spread across the landscape covering much of south Alabama, northwest Florida, and Mississippi. It now can be found in most of Alabama, a large portion of Mississippi, much of Louisiana and Georgia, some of the Carolina’s, Tennessee, and Virginia, and in every county of Florida. It is not only listed as an invasive species in these states, but also as one of the nation’s worst noxious weeds. It quickly covers pastureland. Being serrated and having silica with the grass blades it is not palatable to livestock, you can lose good pastureland when this invades. In natural areas and private timberland, it quickly covers the understory where it burns too hot during prescribed burning efforts and creates a situation where the valuable management method cannot be used. It is not a good plant to have on your land.

In 2020 we were made aware the plant was growing on Perdido Key in Escambia County. We are not sure how it got there but most likely from landscaping equipment that was not cleaned after working an inland area where the plant was present – this is a common method of dispersing the plant. Currently there are 456 records along the coast of the Florida panhandle. 404 of these are on coastal beaches and 52 are on our barrier islands. 44 of the island records are on Santa Rosa/Okaloosa Island, 4 at St. Andrew’s State Park, 1 on Cape Sand Blas, and 1 on St. Vincent Island.

What impact this plant will have on barrier island wildlife is not fully understood. But we know that it has not been beneficial within inland habitats and the potential of having a negative impact is there. Locally we will begin to survey for exact locations on the islands in Escambia County in 2023 and begin a management plan for those, as well as education outreach to reduce potential sources.

Giant Salvinia (Salvinia molesta)

This is a new invasive species to our area and, until recently, was only found within our state in the panhandle. There are now 19 records found in 7 counties across the state; 10 of the 19 records are in Escambia County. This is a freshwater species that prefers quiet backwaters with high levels of nutrients. In our county the plant is concentrated in the upper arms of Bayou Chico. Though an estuary, Bayou Chico has relatively lower salinities than most of our other bayous – the plant is doing well there. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) began management of this area a few years ago, but it is still there and seems to have spread to a nearby retention pond. The best guess as to method of dispersal were beavers seen moving back and forth between the water bodies. We plan to conduct surveys of other nearby retention ponds in 2023.

Though relatively new to Florida, it has had a large impact on the freshwater systems of Texas and Louisiana. I witnessed firsthand that impact at a lake near Shreveport LA where I was camping. This plant is a small one that floats on the surface of the water. It resembles duckweed but the leaves are larger. It had completely covered the surface of the lake and was kept out of the swimming area by using booms. There was no way to fish in the lake and moving through with a paddle craft would have been difficult. It is similar to water hyacinth covered waters. Though the swimming area was clear, the bottom had become “mucky”, and no one was swimming. All water recreation had stopped. The thick canopy covering the surface of the lake blocks sunlight so no submerged grasses can grow, the dead plant material decomposes and draws down the dissolved oxygen levels which could create fish kills.

Knowing this, FWC has a team focused on eradicating this plant from our state before such situations occur here. Though it will not reach our barrier islands by floating there (because of its dislike of salt water) if it DID reach any of the retention ponds near the homes, hotels, and condos, via landscaping equipment used on inland ponds, or some other method, it could be a real problem. And, as we have seen in Bayou Chico, wildlife could move it to the natural freshwater ponds on the island. We will begin surveys of all ponds on Perdido Key and Santa Rosa Island in 2023.

The Brown Anole (Anolis sageri)

This small lizard from Cuba (also known as the Cuban anole) has been in Florida for some time. It most likely reached our shores accidentally by hitchhiking on a boat. With south Florida’s tropical climate, the lizard did quite well and began to disperse north.

I first encountered the creature on campus in Gainesville. Along west side of Ben Hill Griffin Stadium (The Swamp) are trees that are enclosed in wooden boxes – a sort “raised bed” look. When I looked in one of them there were numerous brown lizards scattering everywhere. I checked the next tree and found the same. I found the same in each of the tree boxes along that road. I then began to see them at the rest stops on I-10 between Pensacola and Gainesville. You would step out of the car and as you walked you would see numerous small brown lizards scattering everywhere. The same ones as in Gainesville – the brown anole. I then received a call from a resident on Innerarity Point Road near Perdido Key. She wanted to know what type of lizard she was now seeing in her yard. They were small, brown, had white spots (diamond-like patterns) on their backs and were EVERYWHERE. I asked for a photo, and eventually made a site visit, they were the brown anole. I then began to receive calls from other residents near Perdido Key, then from Gulf Breeze, then from the East Hill area of Pensacola. All the same. The brown anole had made it to Pensacola. Interestingly, when I was speaking to a garden club about invasive species, and was discussing this one, residents from the north end of the county had no idea what I was talking about. They had never seen them. They apparently were invading near the coast. Between 2018-2021 I was conducting a cottonmouth survey on Perdido Key for a Homeowners Association who was encountering a lot of them. At first the brown anoles were not there. Then, during the second year of surveying, I began to see them. The brown anole had reached the barrier island.

It is believed that the mode of dispersal is the same as how they reached Florida in the first place – hitchhiking. Most likely on landscape plants that were grown in south Florida, transported up here, and delivered to you. It is not quite clear how they may impact barrier island wildlife. We know where they show up the native green anole (Anolis carolinensis) begins to decline. Some studies show that the green anoles move higher up in the trees and shrubs where needed resources are limited, and the population will most likely not survive. I have watched green and brown anoles battle it out on my front porch (yes – I have brown anoles in my yard also). I have seen green anoles win these battles – but they seem to have lost the war. I seldom find them anymore. What changes may happen to wildlife on the barrier islands we will learn with time. Though I have not personally seen one on Santa Rosa Island, I am sure they are there – and probably on your barrier island also.

Cuban Treefrog (Osteopilus septentrionalis)

As with the brown anole, it is believed the Cuban treefrog reached our state hitchhiking on a boat. They too have been in the state for quite some time. But records in the Florida panhandle were non-existent. It was believed that the winters here too cold for them. But that appears to be changing.

I have had occasional calls about this frog over the last few years. In each case it was a single individual, hanging on their windows and glass doors, shortly after the homeowner had purchased new plants for landscaping. As with the brown anole, we believe this is a common method for spreading them. But as we mentioned, there was not much concern because our cold winters would keep this invasion at bay. Then there was a report of several Cuban treefrogs at a location on Tyndall AFB in Panama City. They appeared to be breeding and also appeared that they had overwintered. Dr. Steve Johnson (of the University of Florida) later confirmed this to be the first recorded breeding group in the panhandle. And the “love had begun to spread”. More accounts were being reported in the western panhandle. One community in Santa Rosa County found over 100 over the course of a year. Again, we think they are spreading with landscaping plants, or hitchhiking by other methods.

The issue with the animal is similar to that of the brown anole. It is much larger than our native treefrogs and likes to devour them. They are large enough to eat small native lizards and snakes as well. They produce a mild toxin in their skin that can irritate your eyes, nose, and even trigger asthmatic attacks. They have been found in toilets and are known to even plug the plumbing. They have also been found in electrical power boxes and have caused power outages. Overall, they are pain to deal with.

There are currently 28 records in the Florida panhandle. Though some have been found along the coast of our estuaries, there have been no reports on our barrier islands. Maybe we can educate the public on the hitchhiking issue and possibly keep them off the islands. We will be initiating a citizen science effort to monitor their locations on Pensacola Beach and Perdido Key beginning in 2023.

Invasive species, by definition, are a problem for barrier island wildlife. But another problem they are facing is the increase in humans. That will be the topic in part 9.

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 5 – Reproduction - January 12, 2026

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 4 – Thermoregulation - December 29, 2025

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 3 – Envenomation - December 22, 2025