Many who visit a seagrass bed for fishing or snorkeling, see many forms of marine life while there. There are numerous small silver fish darting in and out of the grass, an occasional stingray half buried in the sand waiting to ambush prey, and sometimes a horseshoe crab crawling along looking for a meal. One seagrass community creature they are not aware of, even if they are in front of them, are the sponges.

Those who are not familiar with the creature we call the sponge may think of the synthetic ones purchased at grocery stores and made in a factory somewhere. They are usually colored to match your kitchen or bathroom. Those who are familiar with them associate them more with reefs. Some reef sponges can become quite large and often they are quite numerous out there. But they do not register as a member of the seagrass community with most people. But they are out there.

From a taxonomic point of view sponges are interesting. What is a sponge?

Is plant? animal? fungi?

Well, to classify it using the characteristics of each, we can rule out plants. Plants have cell walls and organelles within some cells to conduct photosynthesis. This is not the case for sponges.

We can also rule out fungi. Though fungi do not photosynthesize, they do have cell walls, and sponges do not.

This leaves animals. Yep… they are animals.

Once you classify it as an animal the next step is to declare it either a vertebrate or invertebrate. Based on the definition of each, this would be an invertebrate – there is no backbone.

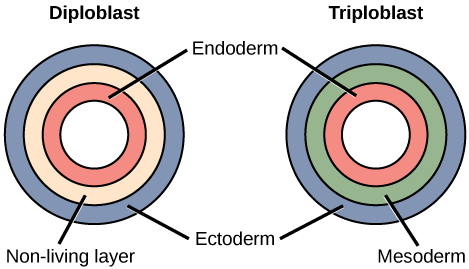

Invertebrates can be further broken down based on their symmetry and which germ layers they possess in the early stages of development – the larval stages.

Most invertebrates are categorized as either having radial or bilateral symmetry. Radial invertebrates have a top and bottom (dorsal and ventral) side, but no head or tail (anterior, posterior). Bilateral invertebrates will have all four. For some sponges, you can find radial symmetry, for others there is no symmetry at all – those would be asymmetrical.

With germ layers you can have ectoderm (the outside cell layer), endoderm (the inside), and mesoderm (the middle layer). Each germ layer develops different structures as the larva grows. If the creature is does not have a specific germ layer, they will not develop those specific structures. Sponges have no germ layers. They do not have true skin, no internal organs, no circulatory, musculature, or nervous system. That is a sponge… the simplest form of animal life on the planet.

When you look at a sponge you do see structure. There are different forms (species) of them and they can be distinguished from each other and named – like “vase sponge”, or “barrel sponge”. But when you look inside of them many have a lot of tissue with canals and channels running all through them. Like what an ant colony would look like underground.

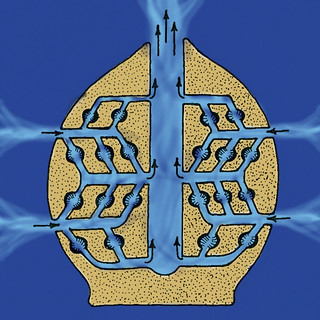

A closer look shows that the exterior wall is very porous (giving them their phylum name Porifera). The water enters these pores and moves all through the massive highways of channels running through the creature. Eventually the water exits the sponge at the top through large pores (or one large pore) called the osculum. The currents that drive this water movement are generated by the flagella of small cells called choanocytes (collar cells). They line the channels by the thousands. Rotating their flagella, they create water movement the way a rotating fan causes air movement. The movement is from the environment into the sponge. Here they collect food from the water (small microscopic creatures and other forms of organic debris), and oxygen.

There are other cells within the lining of the channels called amoebocytes who assist with reproduction. They can encase genetic material (cells) within a hard matrix called a gemmule and “toss it” into the currents where it will exit through the osculum, drift in the ocean currents, and form a new sponge elsewhere. Being simple creatures, they can certainly reproduce asexual by simple cell division. Fragments of sponge will also generate new sponges.

The skeleton that holds these cells into the form we see is a series of hard structures called spicules. Spicules come in different shapes and under the microscope appear to look like thorns, are the “jacks” of a common game played by baby-boomers when they were kids. Some are solid, others a little more flexible, and the material used to make these spicules are used to divide sponges into different classes.

Spicules made from calcium carbonate are hard and scratchy, they are in the Class Calcarea. These are often sold as “luffa’s”. Those made of the more flexible-spongin are in the Class Demospongia and is the largest class of sponges. These are often sold as “bath sponges” and are softer. And then there is the Class Hexactinellida – the “glass sponges”. Their spicules are made of clear silica and they look like they are made of glass. They are more common in the deeper part of the ocean and are beautiful.

In the seagrass beds of the panhandle, you will find sponges from the “bath sponge” group. One common one sold at the Gulf Specimens Lab in Panacea is called “Green Finger Sponge”. As you move through the grasses you will encounter these anchored near the base of the grass. They are usually dark in color, often a dark green almost black, and when opened appear yellow or orange on the inside.

They are full of creatures. Sponge channels provide excellent hiding places for the small creatures who graze on the epiphytes found on the grass blades. All sorts of small crustaceans and worms can be found here. It is like a microhabitat within the grassbed system itself.

The relationship between sponge and grass is complicated. Sponges filter the water, improving water clarity which seagrasses need. However, seagrasses are excellent at trapping and holding sediment, which also improves water clarity but these same sediments can plug the pores of sponges which they need to feed. It is sort of a love/hate relationship between them.

The purpose of this series is to educate you on some of the members of the seagrass community. Sponges are one such creature and most people do not notice them. But they are interesting creatures if you take a look.

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 5 – Reproduction - January 12, 2026

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 4 – Thermoregulation - December 29, 2025

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 3 – Envenomation - December 22, 2025