I attended a meeting recently where one of the participants stated – “We have been looking at a lot of water quality parameters within our bay in recent years, and plan to look at more, but has anyone been looking at temperature?”

What he was referring to was that the focus of most monitoring projects has been nutrients, dissolved oxygen, etc. But most agencies and universities who have been conducting long term monitoring in our bays are collecting temperature data as well. His question was not whether they have or not but has anyone looked at this long-term temperature data to see trends.

I know from some of the citizen science monitoring I have been involved with that temperature is collected but (anecdotally) does not vary much. It is like pH, we collect it, it is there, but does change drastically (anecdotally) over time. However, it has been a very hot year. This “heat dome” that has been sitting over the Midwest and southeast this summer has set records all across the region. Someone monitoring water temperature in East Bay recently reported surface water temperature at 96°F (36°C). Many have stated that swimming in our waters at the moment feels like swimming in bath water. It’s not just warm in your yard, it is warm in the bay. And this brings up the question of thermal tolerance of estuarine species.

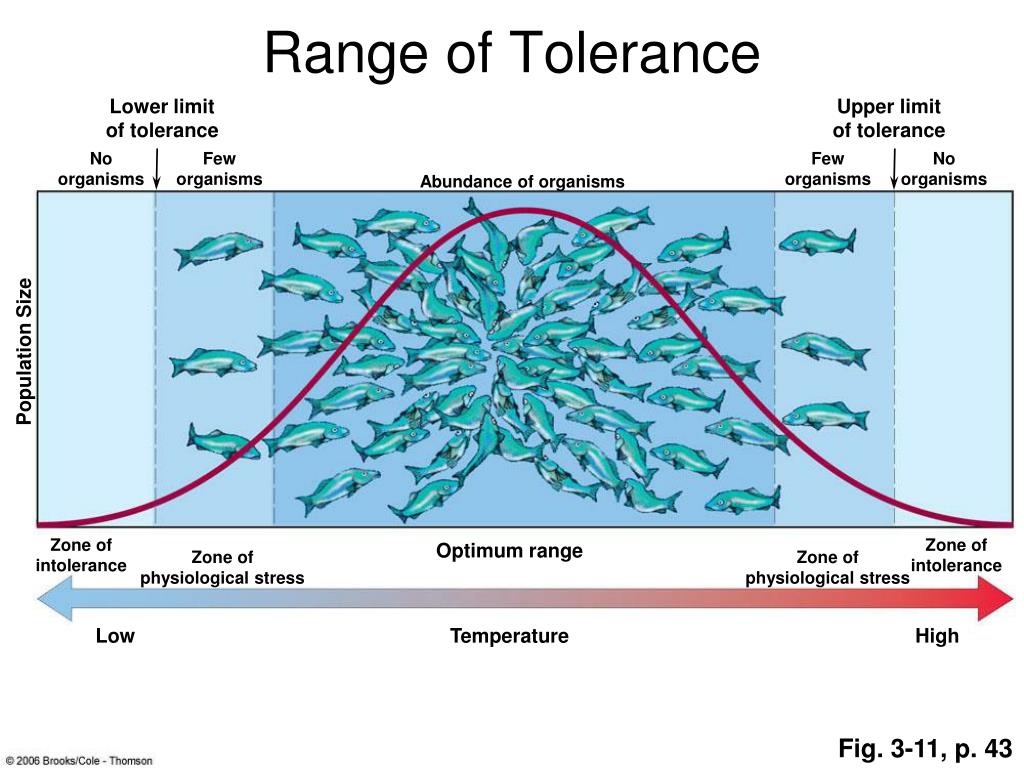

All creatures have a temperature tolerance range. They resemble a bell curve where you have the thermal minimum at one end, the thermal maximum at the other, and the “preferred” temperatures near the top of the bell curve (see image below). Many creatures have a large tolerance for temperature shifts (their bell curves extend over a larger temperature range). You find such creatures in the temperate latitudes where temperature differences between summer and winter are larger. Others have a lower tolerance, such as those who are restricted to polar or tropical latitudes. Within an estuary you can find creatures with varying thermal tolerances. Some have a larger tolerance than others. Ectothermic (cold-blooded) creatures often have a wider range of temperatures they can survive at than endothermic (warm-blooded) ones. Homotherms (creatures who maintain their body temperature near a fixed point – such as humans 98.6°F/37°C) expend a lot of energy to do this. When environmental temperatures rise and fall, they have to expend more to maintain it at their fixed temperatures.

It is also true that most creatures prefer to exist near their thermal maximum. In other words, the bell curve is sort of skewed towards the warmer end of their range. But what is their thermal maximum? What happens when they reach it? How hot can they go?

The studies I reviewed suggested that the thermal maximum is dependent on other environmental factors such as salinity and dissolved oxygen. In most cases, the higher the salinity, the higher the thermal maximum was. I looked at studies for the eastern oyster (Crassostrea virgincia), the brown shrimp (Farfantepenaeus aztectus), the blue crab (Callinectes sapidus), the Spot Croaker (Leiostomus xanthurus), and the pinfish (Lagodon rhomboides). The oyster, shrimp, and blue crab support important commercial fishery. The spot croaker is a dominant fish species in the upper estuary where the pinfish is a dominant species in the lower sections. These studies all suggested that again, depending on salinity, dissolved oxygen, pressure, and rate of temperature increase, the thermal maximum could happen as low as 30°C (86°F) and as high as 40°C (104°F), with many having a thermal maximum between 35-40°C.

At these temperatures proteins begin to denature and biological systems begin to shut down. Most of the studies determined the endpoint at “loss of equilibrium” and not actually death. Our estuaries can certainly reach these temperatures in the summer. Again, one recent reading in East Bay (within the Pensacola Bay system) was 96°F (36°C).

So, what do these creatures do when such temperatures are reached?

The most obvious response is to move, find cooler water. These are often found in deeper portions of the bay below the thermocline (a point in the water column where water temperatures significantly change – usually decreasing with depth). However, many sections of our estuaries are shallow and deep water cannot be found. In these cases, they may move great distances to seek deeper water areas, or even move to the Gulf of Mexico. In some cases – like with oysters – they cannot move, and large die-offs can occur. Other responses include lower metabolic rates and decline in reproduction.

We know that throughout history, there have been warmer summers than others and heat waves have happened. In each case, depending on other environmental factors, estuarine creatures have adapted, and some members have survived, to keep their populations going.

We know that large scale die-offs have occurred in the past and the tougher species have continued on.

We also know that the planet is warming, and it would be interesting to look at how the water temperatures have changed over the last few decades. Are they increasing? Are they reaching the thermal maximums of the creatures within our bay? How will these creatures respond to this?

How hot can they go?

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 5 – Reproduction - January 12, 2026

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 4 – Thermoregulation - December 29, 2025

- Rattlesnakes on Our Barrier Islands; Part 3 – Envenomation - December 22, 2025