Miami is ground zero for invasive species in this state. But the Florida panhandle is no stranger to them. Where they are dealing with Burmese pythons, melaleuca, and who knows how many different species of lizards – we deal with Chinese tallow, Japanese climbing fern, and lionfish. The state spends hundreds of thousands of dollars each year battling and managing these non-native problem species. By definition, invasive species cause environmental and/or economic problems, and those problems will only get worse if we do not spend the money to manage them. Those who work in invasive science and resource management know that the most effective way to manage these species is to detect them early and respond rapidly.

Invasive species have made their way to the coastal waters and dunes of the barrier islands in the Florida panhandle. Beach vitex, Brown anoles, and Chinese tallow are found on most. Recently on Perdido Key near Pensacola, we found a new one – cogongrass.

Cogongrass (Imperata cylindrica) was accidentally introduced to the Gulf coast via crates of satsumas entering the port of Mobile in 1912. It began to spread from there and has covered much of the upland areas of the southeastern U.S. It has created large problems within pasture lands, where livestock will not graze on it, and in pine forest where it has decreased plant and animal biodiversity as well as made prescribed burning a problem – it burns hot, hot enough to actually kill the trees. The impacts and management of this plant in that part of the panhandle has been known for a long time. The Department of Agriculture lists it as one of the most invasive and noxious weeds in the country.

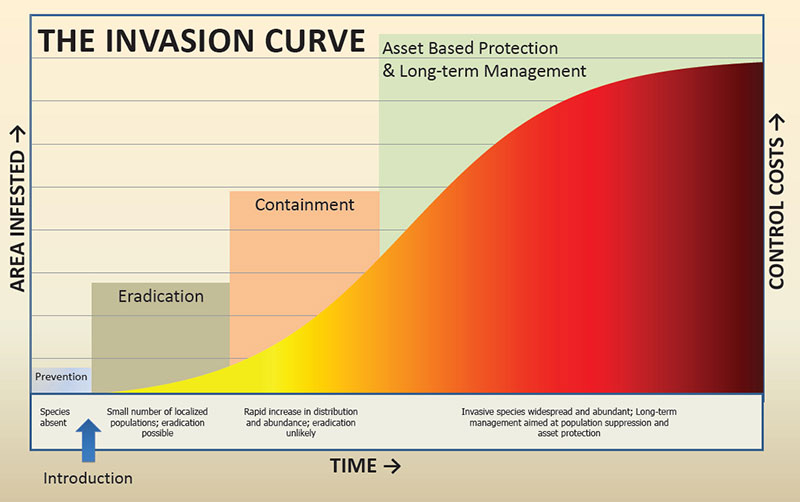

Two years ago cogongrass was discovered growing around a swimming pool area at a condo on Perdido Key. To be considered an invasive species you must (a) be non-native to the area – cogongrass is certainly non-native to our barrier islands, (b) have been introduced by humans (accidentally or intentionally) – strike two, we THINK it was introduced by mowers. This is a common method of spreading cogongrass, mowing an area where it exists, then moving those mowers to new locations without cleaning the equipment. We do not know this is how it got to the island, but the probability is high. Third, it has to be causing an environmental and/or economic problem. It certainly is north of the I-10, but it is not known what issue it may cause on our barrier islands. Could it negatively impact protected beach mice and nesting sea turtle habitat? Could alter the integrity of dunes to reduce their ability to hold sand and protect properties. Could it overtake dune plants lowering both plant and animal diversity thus altering the ecology of the barrier island itself? We do not know. What we do know is that if we want to eradicate it, we need to detect it early and respond rapidly.

According to EDDMapS.org – there are 75 records of cogongrass on the barrier islands, and coastal beaches of the Florida panhandle. This is most likely under reported. So, step one would be to conduct surveys along your islands and beaches. Florida Sea Grant and Escambia County of Marine Resources are doing just that. EDDMaps reports five records on Perdido Key and four at Ft. Pickens. It most likely there is more. A survey of the northeast area of Pensacola Beach (from Casino Beach east and north of Via De Luna Drive) has found two verified records and two unverified (they are on private property, and we cannot approach to verify). Surveys of both islands continue.

The best time to remove/treat cogongrass is in the fall. The key to controlling this plant is destroying the extensive rhizome system. In the upland regions, simple disking has been shown to be effective if you dig during the dry season, when the rhizomes can dry out, and if you disk deep enough to get all of the rhizomes. Though the rhizomes can be found as deep as four feet, most are within six inches and at least a six-inch disking is recommended. Depending on the property, this may not be an option on our barrier islands. But if you have a small patch in your yard, you might be able to dig much of it up.

Chemical treatments have had some success. Prometon (Pramitol), tebuthurion (Spike), and imazapyr have all had some success along roadsides and in ditches north of I-10. However, the strength of these chemicals will impede new growth, or plantings of new plants, for up to six months. There are plants that are protected on our islands and on Perdido Key any altering of beach mouse habitat is illegal. We certainly do not want to kill plants that are holding our dunes. If you feel chemical treatment may be needed for your property, contact the county extension office for advice.

Most recommend a mixture of burning, disking, and chemical treatment. But again, this is not realistic for barrier islands. Any mechanical removal should be conducted in the summer to remove thatch and all older and dead cogongrass. As new shoots emerge in late summer and early fall herbicides can then be used to kill the young plants. Studies and practice have found complete eradication is difficult. It is also recommended not to attempt any management while in seed (in spring). Tractors, mowers, etc. can collect the seeds and, when the mowers are moved to new locations, spread the problem. If all mowing/disking equipment can be cleaned after treatment – this is highly recommended.

Step one would be to determine if you have cogongrass on your property, then seek advice on how to best manage it. For more information on this species, contact your local extension office.

- Our Environment: Part 10 – Improving Agriculture - June 20, 2025

- Marine Creatures of the Northern Gulf – Snails and Slugs - June 20, 2025

- Our Environment: Part 9 – Agriculture Challenges - June 6, 2025