They’re consumed worldwide, from 5-star exclusive restaurants overseas to your flip-flop beach bars right here in the Florida Panhandle. They have many different preparation techniques, such as plain and simple with a squeeze of lemon and a dash of hot sauce to “dip-your-bread-innit” chargrilled parmesan Cajun garlic butter (recipe below). However, many of their consumers actually don’t know what an oyster is, and as luck would have it, here’s a quick oyster 101!

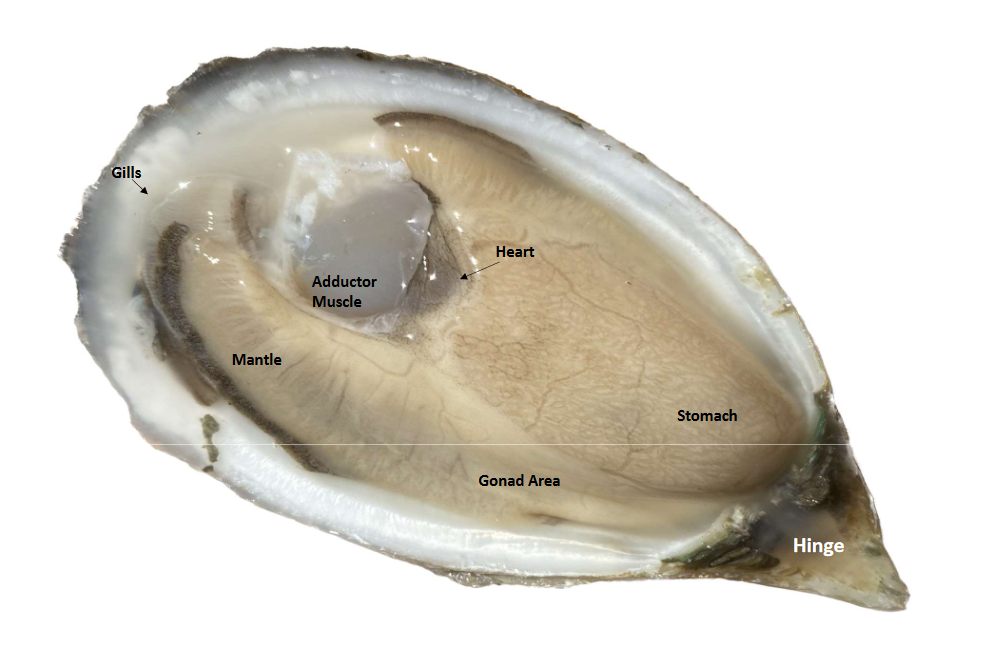

Anatomy

Many people ask me what exactly an oyster is? Before becoming an oyster farmer, I always referred to them as “rocks with tasty meat in them,” but I couldn’t be further from the truth. Oysters are actually complex individuals that go through many metamorphoses and transitions throughout the first 2-4 weeks of their life, this includes a period of free-swimming followed by walking around with its “foot.” Let us look under an oyster’s top shell and identify some key organs.

Mantle – A very thin, dark, fleshy layer of tissue that surrounds the oyster’s body. This is where shell formation begins!

Hinge – The shucker’s worst nightmare. This, along with the adductor muscle, is responsible for the opening and closing of the shell.

Adductor Muscle – Helps keep the oyster shut and protected from any predators. This part must be severed in order to fully open the oyster.

Gills – Thin, delicate structures found inside the body of the oyster. They serve a crucial role in respiration and feeding. Gills are shaped like tiny, finger-like projections that provide a large surface area for oxygen extraction, and they also trap and transport food towards the mouth.

Heart – Oysters have a simple circulatory system with a three-chambered heart that pumps colorless hemolymph throughout their body to distribute nutrients and oxygen.

Biology

Crassostrea virginica (or as we know them, the Eastern oyster) is a native species of oyster that is commonly found along the eastern coast of the USA, from the upper New England states all the way to the southernmost tip of Texas. Eastern oysters prefer an estuarine environment (mid-salinity) but can be found in some coastal areas with higher salinities, especially in south Florida. As filter feeders, they trap nutrients like plankton and algae from the environment and require a habitat that can handle their filtering power (30 gallons per day).

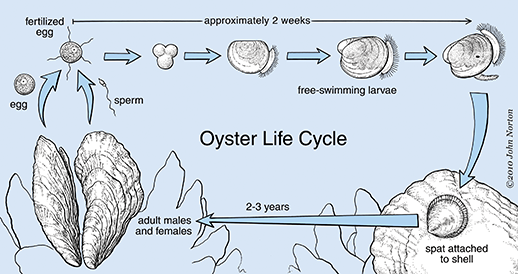

The first 2 – 3 weeks of an oyster’s life is completely different than most people expect from an oyster. Females and males coordinate their spawning time with different cues and release massive amounts of eggs and sperm into the water. This type of spawning behavior is considered batch spawning, and a majority of the fertilized eggs perish before adulthood due to predation and other environmental causes. Once fertilized, the fertilized eggs go through multiple divisions and approximately 12-24 hours later, the free-swimming trochophore larvae are formed. These larvae swim around in the water column for 2-3 weeks, developing their shell and forming into a veliger, which closely resembles their adult stage. Once ready to settle, the pediveliger is formed. The pediveliger has a “foot” and walks around the bottom, looking for a suitable place to settle (usually another oyster). Once a suitable location has been found, the foot will secrete a substance to cement them into place and the pediveliger will metamorphose into a juvenile oyster, also known as spat. Oysters can grow very rapidly after their settlement, with oysters reaching 3 inches (usual harvest size) within 18 months.

Oysters have been known to establish massive reefs in estuaries, but their numbers have been on a rapid decline across the southern USA since the 1960s. These oyster reefs provided a massive natural, biological filter in the bays, and also were home to many juvenile and adult fish and crustaceans. Currently, there are many agencies and foundations that have oyster restoration at the top of their agenda, and the future is looking brighter for the oyster populations.

Pearls of Wisdom

I hope this quick oyster 101 helped shed light on the otherwise unknown life of the Eastern oyster. With the holidays coming up, make sure you grab some oysters to shuck and share with family and friends, and look at their shocked faces when you bust out all this wonderful oyster knowledge. Who knew that an oyster was much, much more than a “rock with some meat in it.”

“Dip-Your-Bread-Innit” Chargrilled Oysters

24 Oysters

2 Sticks of Butter

2 Tablespoons (or more) of Cajun Seasoning (Uncle Tony, Zatarains, etc)

½ cup of Hot Sauce

½ cup of Lemon Juice

1 Tablespoon of Granulated Garlic

2 cups of Mozzarella Cheese

½ cup of Parmesan

1 Cup Panko (The Razzle-Dazzle)

Sliced Bread (Baguette, Wonder, any bread honestly)

———————————————————————————————————

- Shuck Oysters – Many instructional videos online, and make sure you use an actual oyster knife, clam knives are no good!

- Add butter to pan/pot. Melt the butter on medium, then add everything but the oysters and cheese to the butter.

- Start your grill, charcoal/wood is best for adding a smoky flavor. Once the butter mixture is made, add oysters to the grill and spoon your butter mixture into the oysters.

- Mix the cheeses together and add the cheese mixture to the oysters once the butter is spooned on. For a little razzle-dazzle, mix 1 cup of panko into the cheese mixture.

- Cook oysters until bubbling. Make sure to not overcook the oysters, and once you seed the mixture bubbling, they are good to remove.

- Eat the oysters and dip your bread in the shell to soak up the juices. You won’t regret it.

- Aquaculture 101: Aquaculture in The USA - May 12, 2025

- Aquaculture 101: The History of Aquaculture - April 25, 2025

- A Northwest Florida Winter Wonderland - January 31, 2025