Recently I attended a workshop on wildlife tagging projects. Researchers from across the Gulf of Mexico who had projects going on in the northern Gulf were invited to present their updates. I was there to help present what we have learned about diamondback terrapins but there were numerous other talks, and the results were fascinating. Fascinating enough that I thought the public would be interested in them as well. Most of the presentations were on fish or reptiles, but the fish included interesting species such as whale sharks, tiger sharks, cobia, and tarpon. So, I am going to run a series of posts on the different species along with another series on barrier island wildlife.

I thought I would start with an introduction on the methods of wildlife tagging and why scientists tag animals. Some of the reasons may seem obvious, but with today’s modern tags, there is a lot of information scientists can gain from doing this.

Why do they tag?

With the types of tags they used when I was in school there were a few things that you could learn. (1) How far do the animals range, (2) how fast they reached those locations, (3) some idea of live longevity – you at least knew how long they were “at freedom”. With these data you could get a better idea of what their habitat range was and how they used the habitat. Some, like blue sharks, may move great distances all year long. Others, like nurse sharks, may not move more than a few miles from the point where they were tagged. Others may move seasonally, spending summer in one region and winter in another. All of these data are useful to resource managers responsible for maintaining the species population.

With the more modern electronic tags, they can learn such things as how deep they dive, how long they stay at depth, what water temperatures they may frequent, what salinity they prefer, and let you know where the animal is at any given moment in time. Today’s tags are pretty amazing.

How do they tag?

Well… step one to answering this question is HOW DO YOU CATCH THE ANIMAL? – not as easy as you think. Whale sharks and leatherback sea turtles are quite a handful. If your target species is something like a white shark, tiger shark, diamondback rattlesnake, there is an extra danger added. As you plan a method for your safety, you must also plan a method for their safety. The objective is not harm or kill the creature – you will learn nothing from this. When I began my career, I saw a program on how they tagged polar bears in the 1980s. They would fly over the ice in a helicopter looking for the bears. When the bears saw the helicopter, they would run for the safety of water. The scientist would try to shoot a dart into the animal to put it asleep long enough to get a tag on it. BUT if you overdosed the bear, and it made it to the water, it could drown. So, from the air, they had to gauge the weight of the bear, guess what amount of the drug to shoot, and hope they were right. If the bear did fall asleep, how “asleep was it? Did you give ENOUGH drug? Polar bears can be very dangerous. In the episode I watched the bear was asleep, but the researchers did mention that they will “play sleep” and you need to be ready. Such was the world of wildlife tagging 40 years ago.

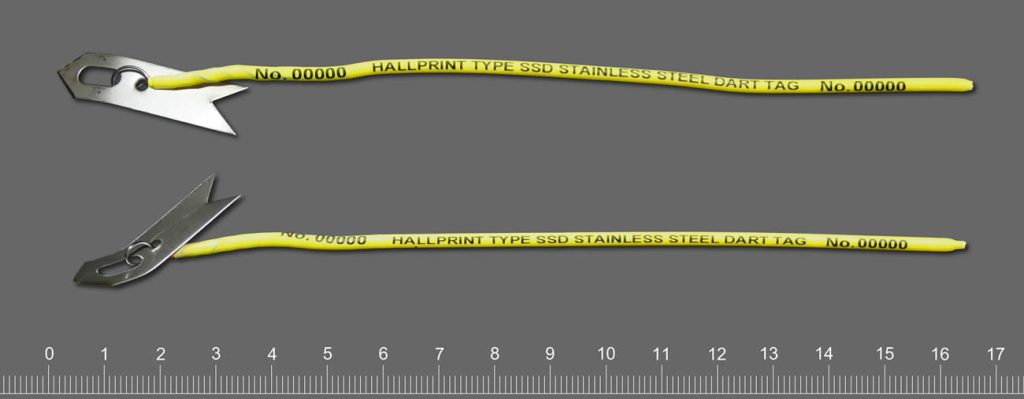

One of the things that was also discussed when I was in school was what type of tag you were going to place on the animal. They did not have the neat tools they have now. Most tags had a capsule with a piece of paper, sometimes written in multiple languages, to call said person and report where and when they found the animal. There was usually a monetary award for doing so, or sometimes a hat or T-shirt. I remember the hat you got for reporting a tagged redfish was really neat, but I never caught a tagged one.

You did not want to place a tag that would alter the natural behavior of the animal. In the case of the polar bear, they would place an ear tag and paint a large number on its side in black paint. This made sense from the biologist’s side – flying over the ice you could see the large black “3” on a bear and know the individual. But that large black number could also be seen by their prey. Not good. I saw researchers painting the shells of gopher tortoises with all sorts of neon colors to make detection by them easier, but easier for their predators as well.

Radio tagging was used 40 years ago. This involves capturing the animal (as we have already seen – fun in itself), putting it asleep and attaching/inserting a radio tag. This tag provides a radio signal that can be detected by a receiver carried by the research holding an antenna walking/driving around following the animal. You had to be within range to hear the signal and – honestly – good at detecting the signal. Some researchers were better at this than others. As you can imagine this was only as good as your ability to keep up with the animal. At some point your car/boat would need fuel, or the animal crossed a river you could not. It provided some good data, but there were limits.

Today modern tags have solved a lot of these issues. Some new tags do not have typed notes but sensors that can detect the elevation/depth, temperature/salinity, all sorts of information that was unknown in my college days. These tags can be retrieved and downloaded on a computer to give a much better idea of how the animal spends its time and what it seeks.

Satellite tags work well for creatures who surface frequently – sea turtles, whales, whale sharks. Satellites can detect them, and you can follow their movements/habitat preferences as they are actually using them.

For species at depth, like some sharks, cobia, tarpon, etc. there are now acoustic tags. The tag emits a signal that is detected by an array of receivers the researchers place in the environment. As the animal passes within range of the receiver it is detected, and the downloaded data gives a similar picture of how the animal uses the environment. A couple of neat things about acoustic tags are that (a) you can track satellite tagged animals while they are diving, and (b) your receivers can detect other species tagged by other researchers and let them know where their creature was. This was one reason for the workshop – so, everyone could meet everyone else and know who has tagged what and how to share information.

No tag is permanent. All are designed to fall off. Battery power will eventually fail. But no animal is stuck with this all of their lives as they could have been when I was in school. In future articles we will look at the results of some of these studies.

- Our Environment: Part 11 – We Need Water - July 7, 2025

- Our Environment: Part 10 – Improving Agriculture - June 20, 2025

- Marine Creatures of the Northern Gulf – Snails and Slugs - June 20, 2025