by Carrie Stevenson | Jun 4, 2020

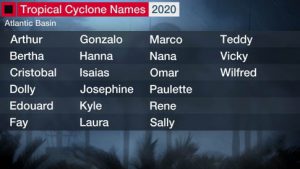

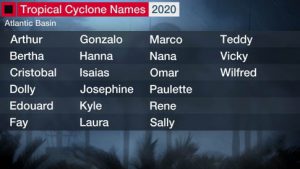

The lineup of 2020 tropical storm names. Tropical storm “Cristobal” is currently headed towards the northern Gulf of Mexico. Photo credit: The Weather Channel

This past March, many people spoke about sensing a sort of free-floating anxiety, waiting for potential disaster to land at their doorstep. The unknowns we faced as COVID-19 cases increased in the United States were not quite like anything we’d previously experienced, although it felt comparable to knowing a hurricane was about to make landfall. After this virus, perhaps, a hurricane seems like a relief—at least we know what to expect and approximately where the most damage will occur. However, big tropical storms carry with them their own set of unpredictable factors like direction and strength at landfall. But the storm-hardiness of our homes, our tree choices, smart evacuation plans—these we can control. Well-thought out precautions can make the difference between getting right back on your feet after a storm and losing almost everything.

Aluminum shutters are one of the many preventative measures Florida homeowners can include in their hurricane preparedness.

Photo: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

No matter how well you have planned for a hurricane, unexpected issues always come up. However, being ready can cut down on the fear and worry.

A few of those preparedness factors include:

* An evacuation plan

* A hurricane kit

* Home wind mitigation techniques

* Tree evaluation

* Wind/flood insurance

I will discuss each of these topics in depth over the next few weeks. Particularly if you are new to the area or never experienced a hurricane, be sure to review good readiness websites, check out these apps, and see which tips might be the most useful to you and your family as we enter the already-active 2020 hurricane season.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 29, 2020

Baby terns on Pensacola Beach are camouflaged in plain sight on the sand. This coloration protects them from predators but can also make them vulnerable to people walking through nesting areas. Photo credit: UF IFAS Extension

The controversial incident recently in New York between a birdwatcher and a dog owner got me thinking about outdoor ethics. Most of us are familiar with the “leave no trace” principles of “taking only photographs and leaving only footprints.” This concept is vital to keeping our natural places beautiful, clean, and safe. However, there are several other matters of ethics and courtesy one should consider when spending time outdoors.

- On our Gulf beaches in the summer, sea turtles and shorebirds are nesting. The presence of this type of wildlife is an integral part of why people want to visit our shores—to see animals they can’t see at home, and to know there’s a place in the world where this natural beauty exists. Bird and turtle eggs are fragile, and the newly hatched young are extremely vulnerable. Signage is up all over, so please observe speed limits, avoid marked nesting areas, and don’t feed or chase birds. Flying away from a perceived predator expends unnecessary energy that birds need to care for young, find food, and avoid other threats.

When on a multi-use trail, it is important to use common courtesy to prevent accidents. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

- On a trail, the rules of thumb are these: hikers yield to equestrians, cyclists yield to all other users, and anyone on a trail should announce themselves when passing another person from behind.

- Obey leash laws, and keep your leash short when approaching someone else to prevent unwanted encounters between pets, wildlife, or other people. Keep in mind that some dogs frighten easily and respond aggressively regardless of how well-trained your dog is. In addition, young children or adults with physical limitations can be knocked down by an overly friendly pet.

- Keep plenty of space between your group and others when visiting parks and beaches. This not only abides by current health recommendations, but also allows for privacy, quiet, and avoidance of physically disturbing others with a stray ball or Frisbee.

Summer is beautiful in northwest Florida, and we welcome visitors from all over the world. Common courtesy will help make everyone’s experience enjoyable.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 22, 2020

Sea pork comes in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Recently I was walking the beach, enjoying a sunset and looking around at the shells and other oddities in the wrack line where waves deposit their floating treasures. Something bright green and oblong caught my eye. It was emerald in color, smooth yet fuzzy at the same time, and firm to the touch. At first, I thought it was a sea bean–a collective term for the many species of seeds and fruits that float to our shores from tropical locations in the Caribbean or Central/South America. The bright green definitely seemed like something botanical in nature. However, the vast majority of sea beans have a woody, protective shell similar to our more familiar pecans or acorns.

I remembered a family member asking about finding a mystery chunk of pink mass she found on the beach a few years ago. It resembled a pork chop more than anything else.

A different variety of sea pork that really lives up to its name. Photo credit: Stephanie Stevenson, Duval County Master Gardener

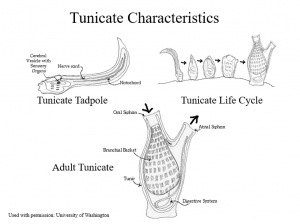

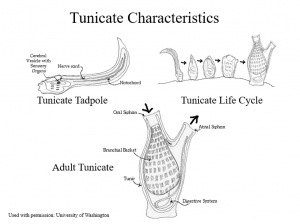

Looking closer and consulting a couple of resources, I realized we had both (most likely!) happened upon one of the oddest and often-questioned finds on our beaches: sea pork. Ranging in color from beige and pale pink to red or green, sea pork is a tunicate (or sea squirt), a member of the Phylum Chordata, home to all the vertebrate and semi-vertebrate animals. While they look and feel more like a cross between invertebrate slugs or sponges, the tunicates are more advanced organisms, possessing a primitive backbone in their larval “tadpole” form. Despite their blob-like appearance, they are more closely related to vertebrate animals than they are to corals or sponges.

The unusual life cycle of the tunicate. Photo credit: University of Washington, used with permission with Florida Master Naturalist program

During their short (just hours-long) larval stage, the tunicate larvae uses its nerve cord (supported by a notochord similar to a vertebrate spine) to communicate with a cerebral vesicle, which works like a brain. Similar to fish, this primitive brain uses an otolith to orient itself in the water, and an eyespot to detect light. These brain-like tools are utilized to locate an appropriate location to settle permanently. Using a sticky substance, the tunicate will attach its head directly to a hard surface (rocks, boats, docks, etc.) and go through a metamorphosis of sorts. The tunicate reabsorbs its tail and starts forming the shape and structure it needs for adulthood.

As an adult, the organism has a barrel shape covered by a tough tunic-like skin (hence “tunicate”). Adult bodies have two siphons, one to bring water in, another to shoot it out (giving them their other nickname, the sea squirt). The water passes through an atrium with organs that allow it to filter feed, trapping plankton and oxygen. The tunicates will spend most of their lives attached to a surface, pumping water in and out as filter feeders. They may be solitary or live in colonies, and vary widely in color and shape, lending variety to those chunks of sea pork found washing up.

I am still awaiting positive identification from an expert on my green find to confirm that it is, indeed, a tunicate and not an unfamiliar plant. Consulting with Extension colleagues, for now we are pretty confidently going with green sea pork. If you have seen one of these before or something resembling sea pork, let us know! It is fascinating to see the variety and unusual shapes and colors.

.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 15, 2020

Crawfish boils are popular in the springtime. Crawfish are generally harvested from aquaculture operations. Photo credit: Libbie Johnson, UF IFAS Extension

“You get a line, I’ll get a pole, we’ll go down to the crawdad hole, honey, baby, mine“…there are lots of great zydeco songs singing the praises of crawfish (aka crayfish, crawdads, mudbugs). They are in season now, and while crawfish festivals all around the southeast are canceled due to concerns over COVID-19, they are still available and make for great eating. Most of us would recognize a cooked one alongside a feast of corn and potatoes, but would you know an actual crawfish hole if you came up on it?

Last fall, our office welcomed about 500 kids (over several days) to the 4-H camp in Barrineau Park for a field trip. I showed every single one of them a small muddy mound with an opening in the top, and asked if anyone could tell me what it was. Not a single kid knew! Now, I make sure I point crawfish mounds out to anyone I happen to be walking with, as they are fascinating little structures. Also referred to as crawfish chimneys due to their upright, open construction, they are built by a crawfish in a muddy area, often near a creek or other water source.

Crawfish mounds are constructed using small pellets of mud, and the opening connects down to a burrow. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

The industrious invertebrate uses its legs and mouth to create pellets of mud as it digs its burrow. It places mud up above the ground, using the mud balls like small bricks. Bricking up the entrance to its burrow (as opposed to placing discarded mud elsewhere) also protects a crawfish from exposure to predators on open soil. The crawfish chimneys can be 6 inches tall (or more!) and connect down to a burrow that may reach 3 feet deep, some straight down and others with side tunnels extending different directions.

Since the crawfish lives in wetland areas, it is theorized that these chimneys extending above the soil allow for better oxygen flow in the burrow. During a drought, crawfish will plug the opening of their mounds with mud, to keep water in the burrow from evaporating.

Crawfish in the wild are rarely harvested, although some folks do fish for them like the song referenced earlier. For the vast majority of crawfish harvested in commercial production, two species are the most popular–the white river crawfish (Procambarus zonangulus) and red swamp crawfish (Procambarus clarkii). They are typically farmed in coordination with rice, as both commodities thrive in flooded conditions. Most aquaculture operations are associated with Louisiana, but at least five other southern U.S. states farm crawfish. To learn more about this industry, check out LSU AgCenter’s informative video.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 8, 2020

In ecology, a “keystone” species is as crucial to an ecosystem as the central stone in this arch.

In architecture, a “keystone” is the top, central block in an arch structure, the one that holds the entire building up. Without it, the bricks around it collapse. With it, there is nothing stronger.

So, when you hear an animal referred to as a “keystone” species, it should get your attention—especially when that species is listed as threatened by state and federal wildlife agencies. In northwest Florida, one of the species upon which the entire longleaf ecosystem is built is the humble gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus).

Gopher tortoises are long-lived, protected by their thick shells and deep burrows. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Once hunted for food and currently in competition with humans for buildable land, this long-lived reptile is an architect in its own right. The tortoises are called “gophers” because of their tunnel building and burrow construction expertise. The tortoises spend about 80% of their time near their burrows, of which they have multiple over their lifetimes. Being a cold-blooded reptile, the burrows allow the tortoises a place to live in the temperature-regulated soil.

The average adult gopher tortoise is about 9-11 inches long, although they can be larger. They have thick feet resembling those of an elephant, and scaly front legs used for digging and burrowing. They are tan, brown, or gray, and live in dry, sandy, upland habitats. Their propensity for dry forestland is typically why their populations are in peril, as this is also the best land for building and development.

The average gopher tortoise’s burrow is 6.5 feet deep and 15-40 feet long, and provides habitat for 350 other species! Those commensal species that share its burrow are mostly invertebrates, but at least 50 are larger backboned species like frogs, snakes, rabbits, and burrowing owls. During forest fires, there are stories of multiple species—from deer and snakes and turtles—calling a truce and hiding in the burrows together until the flames blow over.

Gopher tortoises are nesting right now–be sure to observe from a distance!

Right now—from May to July—is nesting season for gopher tortoises. They lay eggs in the soft sand of their burrow apron, which is the triangular spread of loose sand at the opening of the burrow. Eggs incubate all summer and emerge between August and November. The newly hatched tortoises can expect to live 40 to 60 years in the wild. They live on a variety of grasses and low-growing plants native to longleaf pine, oak forests, and coastal dunes, including wiregrass and gopher apple. They are adapted to routine fires, as they are safe in their burrows and the new growth after a burn provides an abundance of their grassy food sources.