by Carrie Stevenson | May 17, 2019

Aluminum shutters are one of the many preventative measures panhandle homeowners can include in their hurricane preparedness.

Photo: Carrie Stevenson

Hurricane Season in the Gulf and Atlantic begins June 1. For those of us who have lived in hurricane territory for some time, we all have our war stories of days without electricity and water, of being stuck in evacuation traffic, and of neighborhood camaraderie in the aftermath. Whether a newcomer or a native, it is always important to plan ahead and not be complacent about storm readiness. The last few summers have borne out the climate predictions of stronger storms, with many of our neighbors still struggling to dig out of the immense damage done by Category 5 Hurricane Michael last fall.

In this article, I will be paraphrasing a section from the well-done Homeowners Handbook to Prepare for Natural Hazards. A new version of this guide will be coming out soon, but I highly recommend the handbook (hard copies available at many Extension offices) for anyone living in Florida.

Tip #1: Gather your emergency supplies. Do this sooner than later—when a storm is in the Gulf with a trajectory towards your city is not the time to go shopping. Lines will be long, people will be stressed, and shelves will start to empty. Gather emergency supplies like water, canned goods, batteries, and flashlights (full list here) now, and restock monthly throughout the summer and fall.

Tip #2: Create a separate evacuation plan for natural events, such as hurricanes/tropical storms, tornadoes, floods, and wildfires. Northwest Florida is prone to all of these natural phenomena, and the plan required for each is different. For a tornado or tropical storm you will most likely shelter in place (unless your home is not secure in this situation), while fires, flooding, and strong hurricanes may require securing your home and leaving town.

Tip #3: Know you property and take appropriate action. Look at your location—if the land floods during a rain, consider flood insurance. If trees overhang your house, consider trimming or cutting branches that might damage your house in a storm. If the property has a high structural profile, it could be especially susceptible to wind damage in a hurricane.

Tip #4: Know your house and take appropriate action. When was your house built? Does it have connectors to tie the roof to the wall or the wall to the foundation? When will you need to reroof? Look at your blueprints—if you don’t have a copy, your homebuilder or local building department may have copies.

Tip #5: Strengthen your house. A house built after the early to mid-1990’s should have hurricane clips tying the roof to the wall and strong connectors from the wall to the foundation. If your house was built before then, you can still retrofit at a reasonable cost. Wind-rated garage doors, precut shutters, and replacing windows with impact-resistant glass can all protect your home. In the western Panhandle, 75% of retrofit costs can be covered through the Rebuild Northwest Florida wind mitigation program.

Tip #6: Utilize the State of Florida’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program. This program can be used for a number of home improvements, including construction of a safe room for tornado shelter.

Tip #7: Insurance. Don’t gamble with your house. Obtain adequate wind, flood, and home insurance. Remember—if there is a hurricane in the Gulf, insurance companies will not issue windstorm policies.

Tip #8: Take advantage of potential discounts for your hurricane insurance premiums. Coverage may vary among insurance companies, so call you insurance agent to find out about discounts that may be available. Significant discounts may be provided for reducing the risk to your house with window protection, roof-to-wall tie downs, and wall-to-foundation tie downs.

Tip #9: Finance creatively. Consider efforts to strengthen your house as an important home improvement project. Most projects are not that expensive. For the most costly ones, a small home improvement loan and potential discounts from hurricane insurance premiums may make these projects within reach. It is a great investment to strengthen your house and provide more protection to your family.

Tip #10: Seek the assistance of a qualified, license architect, structural engineer, or contractor. There are some improvements that can be done yourself, but if you cannot do the work, seek qualified assistance through trusted references from friends and family and professional associations.

For more information, reach out to your county Emergency Management department or visit these IFAS Extension Hurricane Preparedness and Recovery resources.

by Carrie Stevenson | Oct 26, 2018

Large trees can cause serious damage in a storm, but it is important to salvage as many as surviving trees as possible. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

It has been more than two weeks since devastating Hurricane Michael landed hard on the coast of Florida. Central-Panhandle counties from the Gulf to the Alabama line are in full recovery mode, struggling to return to normal after many days without power and clean water. A strong category 4 hurricane, Michael brought sustained winds of 155 mph, with gusts likely much higher—many instruments that measured wind speed failed and blew away with the onslaught of the storm.

Unfortunately, with winds this strong, trees of every shape and description blew down, bringing with them serious damage to homes, vehicles, and power lines. In the immediate aftermath of a storm, it is important to perform “tree triage” using the same method as emergency room personnel as they decide which patients to treat first, based on urgency.

Hazard trees causing or leading to unsafe conditions should be given priority. These would be limbs and trunks on top of houses, power lines, blocking roads, or leaning in precarious situations that could blow down on people or property. Once roads are cleared and dangerous trees and limbs are removed, homeowners can move their attention to downed trees that are lying out of harm’s way or leaning away from property.

It is important to remember that many injuries from hurricanes happen after a storm—often when physically and emotionally exhausted storm victims are using heavy machinery at elevated heights. Always be willing to ask for help, whether from volunteers, neighbors, or landscape professionals. Use proper safety precautions when utilizing chainsaws, ladders, tractors, and other machinery.

On a more positive note, many trees can be salvaged after a storm. In particular, younger, newly planted trees can often be righted or pruned and still grow to maturity. Don’t fall into the trap of clearing every tree from your property—healthy or not—out of fear. Trees are extraordinarily valuable, and particularly with all of the tree loss it is more important than ever to save as many trees as you can. These trees will provide much-needed shade, oxygen, air and stormwater filtration, and wildlife habitat. Learn the names of your trees that survived or had less damage, and plant more of those after recovery. Many long-lived species like magnolia, live oak, and cypress can weather storms better than other species.

It is important to continue monitoring any surviving trees for damage. Many trees, particularly pines, can be susceptible to disease, insect damage, and fungus after a storm and it may be several months before the damage is fully evident. After Hurricane Ivan, many pine forests and individual trees that survived the storm were lost to pine bark beetles within the following year.

For detailed information on tree assessment and making wise decisions, the IFAS Trees and Hurricanes publication has great photos and examples. Be sure to check it out and contact your local county Extension office if you have questions.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 23, 2018

Local estuaries are a beautiful place to explore with your family. Credit: Matthew Deitch, UF IFAS Extension

Florida’s rivers, springs, wetlands, and estuaries are central features to the identity of northwest Florida. They provide a wide range of services that benefit peoples’ health and well-being in our region. They create recreational opportunities for swimmers, canoers, and kayakers; support diverse wildlife for birders and plant enthusiasts; sustain a vibrant commercial and recreational fishery and shellfishery; serve as corridors for shipping and transportation; and support ecosystems that help to improve water quality. Maintaining these aquatic ecosystem services requires a low level of chemical inputs from the upstream areas that comprise their watersheds.

Aquatic ecosystems are especially sensitive to nitrogen and phosphorus, which are key nutrients for the growth of plants, algae, and bacteria that live in these waters. High levels of these nutrients combined with our sunny weather and warm summer temperatures create conditions that can lead to rapid growth of aquatic plants and algae, which can cover these water bodies and make them no longer enjoyable for people and wildlife. It can also cause dissolved oxygen levels to fall, as plants respire (especially at night, when they are not photosynthesizing) and as bacteria consume oxygen to break down dead plant material. Low dissolved oxygen can create conditions that are deadly for fish and shellfish.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) lists more than 1,400 water bodies (including rivers, springs, wetlands, and estuaries) as impaired by pollutants. Many of these are impaired by excessive nitrogen or phosphorus. It is a daunting challenge to reduce pollutants in these water bodies because their inputs frequently come from all over the landscape, rather than a specific point—nutrients can come from agricultural fields, residential landscapes, septic tanks, atmospheric deposition, and livestock throughout the watershed.

In Florida, FDEP has begun a program to reduce nutrient concentrations in impaired watersheds by collaborating with landowners and other stakeholders to develop management programs to reduce pollutants entering the state’s waters. This pollutant reduction program is currently focused on Florida’s spring systems, including Jackson Blue Spring and Merritt’s Mill Pond in Jackson County. Merritt’s Mill Pond is a 4-mile long, 270-acre pond located near Marianna, and it is a popular regional destination for swimming, boating, kayaking, and fishing in the Panhandle. Its main source is Jackson Blue Spring, which produces, on average, more than 70 million gallons of water each day. Excessive growth of aquatic plants and algae in the pond during summer reduces the area available for swimming and boating. In 2014, FDEP began working with agricultural producers, residents, developers, local government officials, and other stakeholders to identify nutrient contributions in the Merritt’s Mill Pond watershed and develop an action plan to reduce nutrients entering the pond in the coming decades. Collaborations with stakeholders help to improve the accuracy of pollutant estimates, and to ensure the plan is designed appropriately to achieve desired ecological outcomes.

This Action Plan for reducing nutrients into Merritt’s Mill Pond provides an opportunity for land managers to implement their own plans to reduce nutrient contributions without FDEP imposing rigid regulations or mandating particular actions. People can choose from an array of Best Management Practices designed to reduce nutrient contributions, and the state has made funds available for people to help implement these plans. Implementing this Action Plan will restore the wonders of Merritt’s Mill through the 21st Century.

This article was written by: Matthew J Deitch, PhD, Assistant Professor, Watershed Management with the UF IFAS Soil and Water Sciences Department at the West Florida Research and Education Center. For more information, you can contact him at mdeitch@ufl.edu or 850-377-2592.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 6, 2018

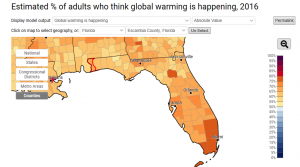

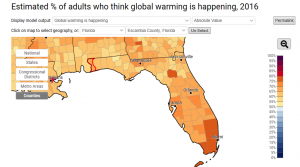

Climate change. Those two simple words have the power to bring about a strong reaction in people. For many, the term is fraught with emotion—with worry, anger, and fear of the unknown. For others, these two words might elicit doubt or frustration. According to a multi-year, nationwide study conducted by George Mason and Yale Universities, as a country we react to the science of climate change along a spectrum of responses. On one end of the spectrum, people are “alarmed” (see a change in climate as a reality and taking action about it) and “concerned” (believe it is a serious issue but have not taken action). In the middle are those in different stages of understanding or awareness of climate issues, and characterized as “cautious”, “disengaged”, or “doubtful.” At the opposite end of the spectrum are the “dismissive”, which are that group of people who are actively opposed to action on climate change and may feel it is a conspiracy. These six categories were based on the responses of a large, in-depth survey conducted in 2008. Ten years later, researchers conducted the study again to see if attitudes had changed. Interestingly, they had—with the most noticeable shift out of the “disengaged” category, as people seemed to cast their lot with one side or the other.

| 2008/2009 |

Yale/George Mason Study Results |

2018 |

| 18% |

Alarmed (+3) |

21% |

| 33% |

Concerned (-3) |

30% |

| 19% |

Cautious (+2) |

21% |

| 12% |

Disengaged (-5) |

7% |

| 11% |

Doubtful (+1) |

12% |

| 7% |

Dismissive (+2) |

9% |

Table 1. 10-year comparison of “Global Warming’s Six Americas” Study. Source: http://climatecommunication.yale.edu/about/projects/global-warmings-six-americas/

Looking at the data, respondents left the “disengaged” group and moved either towards doubtful and dismissive or towards the cautious category. It is likely that the 3% change out of “concerned” moved directly into “alarmed”, as extreme weather events and record temperatures over the last 10 years brought the impacts of a changing climate closer to home.

Data from a national study shows the level of agreement/disagreement on climate-based issues. Source: Yale/George Mason University

When the study is broken down by region, a minority of northwest Floridians believed human activities such as carbon emissions caused climate change. However ~65% of the same group believed climate change was happening (regardless of cause), and 80% responded that our country should fund research looking into renewable energy. The good news here is that while many of us do not agree on the cause of climate change, the majority of us agree on positive steps forward that may relieve some of its results.

For me, the take-home message of this study is that scientific understanding—on many issues, not just climate—is often along a spectrum based on exposure to research, personal interest/relevance, and cultural influences. When explaining any science-based concepts, it is important to know where your listener is coming from and start from there. It is unfortunate that we are in a time when many principles of science are taken as political positions and not products of unbiased scientific method. That being said, great thinkers from Galileo to Hawking have had their run-ins with popular opinion.

As the summer heat cooks on and hurricane season warms up, there will be more articles in the news about climate and its effects. When reading these, look at the source and their intent. Is this an opinion piece/blog with deeply emotional photos and stories meant to sway readers one way or the other? Or is it an agency page, reporting factual data? Time-tested agencies like the National Weather Service (NWS), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and National Aeronautic and Space Administration (NASA) have been keeping historic records of climate data and satellite imagery of ice cover for decades. Use their information to inform yourself, no matter where you might fall upon the “six Americas” spectrum. Worldwide data for climate has been kept since 1880, and both NASA and NOAA climate data found:

- 2016 was the hottest year globally on record

- 2nd and 3rd hottest years on record were 2015 and 2014.

- 16 of the 17 warmest years documented since 1880 have been since 2001

For more information on climate science, check out these resources: Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, NOAA Climate, and NASA Climate.

by Carrie Stevenson | Mar 2, 2018

Bamboo shoots. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

Standing in the midst of a stand of bamboo, it’s easy to feel dwarfed. Smooth and sturdy, the hollow, sectioned woody shoots of this fascinating plant can tower as tall as 70 feet. Unfortunately, bamboo is a real threat to natural ecosystems, moving quickly through wooded areas, wetlands, and neighborhoods, taking out native species as it goes.

We do have one native species referred to as bamboo or cane (Arundinaria gigantea), which is found in reasonable numbers in southeastern wetlands and the banks of rivers. There are over a thousand species of true bamboo, but chief among the invasive varieties that give us trouble is Golden Bamboo (Phyllostachys aurea). Grown in its native Southeast Asia as a food source, building material, or for fishing rods, bamboo is also well known as the primary diet (99%) of the giant panda. In the United States, the plant was brought in as an ornamental—a fast growing vegetative screen that can also be used as flooring material or food. Clumping bamboos can be managed in a landscape, but the invasive, spreading bamboo will grow aggressively via roots and an extensive network of underground rhizomes that might extend more than 100 feet from their origin.

As a perennial grass, bamboo grows straight up, quickly, and can withstand occasional cutting and mowing without impacts to its overall health. However, a repeated program of intensive mowing, as often as you’d mow a lawn and over several years, will be needed to keep the plant under control. Small patches can be dug up, and there has been some success with containing the rhizomes by installing an underground “wall” of wood, plastic, or metal 18” into the soil around a section of bamboo.

Whimsy art Panda in a bamboo forest at the Glendale Nature Preserve. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson

While there are currently no chemical methods of control specifically labeled for bamboo at this time, the herbicides imazapyr (trade name Arsenal and others) or glyphosate (Round-up, Rodeo) applied at high rates can control it. According to research on the topic, “bamboo should be mowed or chopped and allowed to regrow to a height of approximately 3 feet, or until the leaves expand. Glyphosate at a 5% solution or imazapyr as a 1% solution can then be applied directly to the leaves.” These treatments will often need to be repeated as many as four times before succeeding in complete control of bamboo.

Land managers should know that while imazapyr is typically a more effective herbicide for bamboo, it can kill surrounding beneficial trees and shrubs due to its persistence in the contiguous roots and soil. In contrast, glyphosate solutions will only kill the species to which it has been applied and is the best choice for most areas managed by homeowners.

Bamboo Control: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/AG/AG26600.pdf