by Rick O'Connor | Nov 13, 2020

This bio of our friend Shep Eubanks was prepared by Dr. Pete Vergot; Northwest District Extension Director.

Mr. Shepard “Shep” Eubanks, County Extension Director and Extension Agent IV

Shep Eubanks

Gadsden County Extension Director

In 1982 Shepard “Shep” Eubanks began working for the University of Florida as a student in Animal Science where he completed his bachelor’s degree in Animal Science in 1985 and then completed a master’s degree in Animal Science at the University of Florida in 1988. After graduation he started his first position with the University of Florida IFAS Extension as the Livestock Extension Agent I for Columbia County. During this time, Shep cultivated his knowledge and experience of working with farmers and ranchers and introduced his knowledge and love for natural resources and the outdoors. In 1993 Shep was promoted to Extension Agent II with Permanent Status and began his new position in Holmes County Florida as the County Extension Director and Agricultural and Natural Resources Agent where he continued to develop his skills of consulting with farmers, ranchers, and homeowners and a new audience of local county officials. As the County Extension Director, Shep was instrumental in moving from a small three-room office in the Holmes County courthouse to a recently renovated Agricultural Center and Extension office in Bonifay, Florida. Shep hired and worked with a staff of Extension Agents and support staff. In 1997, Shep was promoted to Extension Agent III and in 2003 he was promoted to Extension’s highest rank of Extension Agent IV.

Having an opportunity in 2015 Shep moved “home” to Gadsden County, with his

wonderful wife Genea and their two grown sons, John and Justin, to become the University of Florida IFAS County Extension Director and Agriculture and Natural Resources Extension Agent for Gadsden County. Shep worked with farmers, ranchers, and large landowners and homeowners, assisting them in all areas of agriculture and natural resources providing educational programming leadership and individual consultations to all Gadsden County residents. As the County Extension Director, Shep provided leadership for other Extension Agents and support staff. Shep worked with the former County Extension Director Dr. Henry Grant, along with the Gadsden County Commissioners and leadership, to continue to secure funding and build a new Gadsden County Agricultural Center and convert the older building into the Inman Livestock Pavilion.

Shepard “Shep” Eubanks will always be remembered as a kind and thoughtful person, willing to help and assist everyone that he met. Shep was a mentor to many younger Extension Agents and a friend to all Extension Agents across the Florida Panhandle and the State of Florida.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 13, 2020

This is not a word that most visitors to the beach want to hear. However, shark attacks are actually not that common and the risk is very low. People hear this every year on shark programs, but it does not seem to make them feel any better. Here is what the International Shark Attack File says (as of 2020)…

– Since the year 1580 there have been 3164 unprovoked shark attacks around the world.

Let that sink in for a moment… 3000 unprovoked attacks on humans in the last 440 years.

Now consider the number of car accident victims that have occurred in the last month within the United States. See what they are getting at? Let’s look at more…

– Of the 3164 reported unprovoked attacks (yes… these data only include what was reported) 1483 were from the United States… 47% of them. This may be due to the fact we are “water people”. The other top countries are Australia, South Africa, and Brazil, all “water people” as well.

– Of the 3164 reports 851 were from Florida (27%). This is the number of reported shark attacks in our state since the Spanish settled it. This comes out to 2 each year – though the data shows a sharp increase in attacks starting in the 1970s (most have occurred since then).

– Of the 3164 reports 25 were from the panhandle region (0.8%) and 7 from the Pensacola Bay area (0.2%).

Let that sink in for a moment. Seven reported attacks from the Pensacola Beach area since the time DeLuna landed here in 1559… 7.

And lets once again consider the number of vehicle accidents that will occur in the bay area today.

These numbers have been posted before. Yet people are still very worried when the hear sharks are in the Pensacola Beach region. When attacks occur, they are big news. The International Shark Attack File does give trends and suggestions on what to do. But as many say, sharks are the least of your worries when you are planning a day at the beach.

Now that we have said all of that, they are truly amazing animals.

They are fish but differ in that their skeletons lack hard calcified bone – they are cartilaginous. There are 25 species in 9 different families in the Gulf of Mexico. Many are completely harmless – 13 of the 25 have been reported to have had unprovoked attacks somewhere around the world – the white, tiger, and bull sharks leading the way. Several rarely come close to shore.

Sharks lack a swim bladder and thus cannot “float” in the water column the way your aquarium fish do. Some, like the nurse and angel sharks, rest on the bottom. Others, like the white and blue sharks, swim constantly to get water flowing over their gills.

Because of this, they are very streamlined with reduce scales. They actually have modified teeth for scales – called placoid scales. Their fins are angular and rigid (as are other open water fish) and some can swim quite fast – makos have been clocked at over 30 mph for short distances. Many have seen video of large white sharks exploding with a burst of speed on a sea lion and actually leaping out of the water with it.

Many species do lay eggs, but others keep the eggs within and give live birth after they hatch. One species, the sand tiger, produce four embryos within the mother. The first to hatch consumes the other three!

The teeth of sharks are famous. Rows of them, some pointed, some are serrated, all are designed to cut and swallow. The tiger shark has a serrated tooth that is angled like a can opener. They can use this to “open” sea turtle shells – adding them to their rather large menu. They “shed” these frequently – placing a new sharp tooth where the dull old one was – and will go through tens of thousands of teeth in a lifetime.

The sensory system is one of the most amazing in the world. Tiny gelatinous cells along their sides, called the lateral line, detect pressure waves from great distances. Splashing, thrashing movements made by fish can be detected a mile away – and get their attention. As they approach the sound their sense of smell kicks in. It has been said that a shark can detect one drop of blood in thousands of gallons of water – and it is true. However, the sharks must be down current of the victim to detect it. Their eyes are much better than most think. They have “crystals” within their retina that act as mirrors reflecting light that enters. Imagine turning on a flashlight in a dark room. Now imagine doing this if the walls and ceiling were mirrors – you kind of understand how they can actually see pretty well even in the low light. That said, light does not travel well under water, so they rely on their other senses more. And as if that were not enough. They have small gelatinous cells around the head region that can detect small electric fields. When a shark bites, it must close its eyes and – as the fishermen say – “roll back” out of the head. At this point the shark is basically blind and cannot see the target it is trying to bite. However, if you move out of the way, the weak electric fields produced by your muscles in doing so can be detected by these cells and the shark knows where you are.

Cool – and scary at the same time. Let’s meet a few of these amazing fish in our area.

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/

The nurse shark. Notice the barbels (whiskers) on its head.

Photo: NOAA

Nurse Shark

This is one of the bottom dwelling sharks that appear harmless – and they are – but if provoked, they will bite. They have less angular fins, or a brownish-bronze color, and really like structure – they are found on our reefs. They posses a “whisker-like” structure called a barbel. These are common on other bottom fish, like catfish, and possess chemo-sensory cells to detect prey buried in the sand. They are not as common here as they are in the Keys, but they have been seen. They can reach lengths of 14 feet.

Blacktip sharks are one of the smaller sharks in our area reaching a length of 59 inches. They are known to leap from the water. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Blacktip – Spinner

These are grouped together because (a) they resemble each other, and (b) they are both common here.

They are both stream-lined in shape and have blacktips on their fins. Actually, spinner sharks have more fins tipped-black than the blacktip. The anal fin of the spinner is tipped black, but this is not the case for the blacktip. The spinner gets its name from the habit of leaping from the water and spinning very fast as it does so. Both are quite common in the Gulf and the bay. They reach about eight feet in length and unprovoked attacks are very rare.

The Scalloped Hammerhead is one of five species of hammerheads in the Gulf. It is commonly found in the bays. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Hammerheads

This is a creepy group – check out the head. It is one that many people fear, and unprovoked attacks have occurred. The reader may not know that there are more than one kind – five species actually. They have a tall dorsal fin which sometimes extends above the water when swimming near the surface – the classic “shark is coming” look. Their heads are aerofoil shaped and there are several possible explanations for this. 1) It is more aerodynamic, making it easier for this ram-jetter to swim, using less energy to do so. 2) It is a battery of sensory cells. By swinging the head back and forth, as they do, it is an advanced radar searching for prey, possibly finding it before other sharks do. There are stories of hammerheads arriving first. 3) It is also believed they use their electric sense to detect buried prey – the shape making this easier to find and expose them. It could very well be that all of these could explain the shape.

This pregnant bull shark has an impressive girth.

Bull Shark

Since the film Jaws the world has turned its attention from solely the white shark – to the bull shark. As you can imagine, it is hard for a shark attack victim to tell you which species bit them – “I don’t know… it was a big gray thing chomping on my leg!” or “It was a great white!” because that is the only one many know. But studies sine the 1970s suggest that the bull shark is an aggressive species and may be responsible for a lot of attacks. Particularly in the estuaries and upper estuaries. Bull sharks are what we call euryhaline – they have tolerance for a wide range of salinities. This shark has been reported in low salinities of the upper estuaries and even into freshwater rivers. One report had them over 100 miles from the coast – they are certainly where the people are.

The extremely long upper lobe of the thresher shark.

Image: NOAA

Thresher Sharks

These are bizarre looking sharks. Most sharks have what we call a heterocercal tail – different – different meaning the upper lobe of the forked tail is longer than the lower. But the threshers take this to the extreme – the tail can make up almost half of their body length, which can be 20 feet. It is believed that use this extremely long tail to herd and stun baitfish – their favorite prey. They prefer colder waters and records in the Gulf are not common. Those that exist suggest they live offshore and are rarely encountered near beaches. There are no unprovoked attacks reported from this shark.

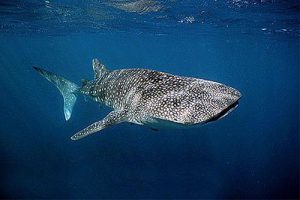

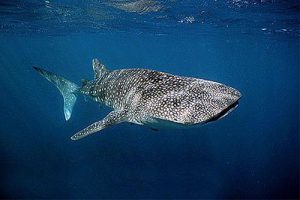

The massive whale shark.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History.

Whale Shark

Amazing… heart stopping… what else can you say. Encounters with the largest fish on our planet are rare – but when they do happen you will never forget it – it will be one of the highlights of your life. As the name suggest – these are large sharks, with a mean length of 45 feet but some reporting in at 60 feet. They are easily recognized first by their size, but also their coloration. They are brownish color with beige or white spots in nice rows running across the dorsal side. They swim slowly filtering plankton from the sea – though will occasionally take in a fish. Some reports show them vertical in the water column moving up and down filtering from a school of plankton or tiny fish. They are rarely seen because they tend to dive deeper during the day with the plankton layer – then surfacing at night following the same plankton. They are, unfortunately, sometimes struck by boats while at the surface.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 6, 2020

Seagrasses have been described as the “nursery of the sea”. Studies show that up to 90% of the commercially valuable fin and shellfish species spend part, or all, of their lives in these submerged meadows. As you can imagine, these grasses must grow in clear, relatively shallow waters – so they are more inshore. You might also imagine that most of the fish living here are going to be small. There are the larger predators in this grassy world, but most are going to be small enough to hide amongst the blades.

These inshore seagrass meadows not only provide hiding places but provide food as well. Interestingly, most do not feed on the grass directly, but rather the tiny plants and animals that are attached to the blades – what are called epiphytes and epizoids. Those that feed on these are then preyed upon by slightly large creatures until we find the larger apex predators – like the speckled trout.

Many of those who reside here are specialist in camouflage and mimicry, and others might be ones who actually live in the sand bordering the edge of the meadows – waiting for a chance to pounce on unsuspecting food. Let’s meet a few of these interesting fish.

Photo: Nicholls State University

Pinfish

You are at the beach for a day of fun and sun. You enter the water of Santa Rosa Sound to play at the edge of the seagrass bed, or maybe to snorkel and explore it. As you stand on the sand you feel little nips at your ankles and immediately think – CRAB! But you would be wrong. As you look closer you will see it came from a small fish – and the more you stir the sand, more of these small fish arrive. They are probably feeding on the small invertebrates that are stirred up from your movement, but they periodically nip at you as well.

This small fish is a very common member of the inshore fish community known as the pinfish. They are members of the Porgy family, related to sheepshead, and have incisor teeth for crushing the shells of their prey. Most locals are first introduced to them as a kid while fishing. They seem to bite, or steal, any bait you put on. Most often used as bait themselves, they are actually edible – but you need one of the large ones to have a meal. They get their common name from the sharp spines of their dorsal fin. When snorkeling in the grassbeds you will find they are the most common fish there.

Photo: USGS

Needlefish

These guys look scarier than they are. Long skinny fish with long skinny snouts that hold long skinny teeth. They resemble barracuda and have the look as if they could attack and do some damage – but they are harmless, unless you catch one in a net, then they will swing their long skinny heads towards your hand for snip.

These small predators travel above the grassbeds looking for potential prey hiding among. Small juvenile fish seem to be what they want. Though often just referred to as “needlefish”, there are actually four species, but they are hard to tell apart.

Photo: NOAA

Seahorses

These are captivating fish, and very hard to find as they blend in so well, but they are there – along with their close cousins the pipefish. It seems hard to call it a fish at all – it certainly does not look like one. Swimming vertically in the water, no tail to speak of, they seem like a creature in their own group. But they are fish. The scales are fused into an armor plating and they do have both gills and fins – characteristics of fish. They will use their prehensile tail to grab onto a grass blade, hanging there waiting for tiny shrimp to swim by which they inhale using a vacuum like motion with their tube-shaped mouths.

Pipefish resemble seahorses but are elongated, with a distinct fin for a tail, and swim horizontally as most fish do. They will turn vertically in the grass to appear to be a blade themselves and hunt similar prey as their seahorse cousins.

A well-known characteristic of this group is the fact that the males carry the fertilized eggs – not the females. Males can be identified by the brood sac on their ventral side and they may carry up to 80 eggs. The eggs hatch within the pouch and the young are born alive.

Photo: NOAA

Puffers

This group of fish are famous for their ability to “blow up”, or inflate like a balloon, when threatened. Kids love to play with them and get a kick out of watching them inflate. These are round bodied – slow moving fish, which is one reason they inflate. It does not matter if you can catch them, you cannot swallow them if you do!

There are actually two different families of “blowfish”. The true puffers are smaller (3-12 inches), have tubercles on their bodies instead of long spines, and the teeth in the upper and lower jaw have a space forming four teeth (two on the top jaw, two on the bottom) – giving them their family name “tetradontidae”. The “burrfish” are larger in size (1-2 feet), have long spines on the body, and no median in the teeth – so only one tooth on the top jaw, one on the bottom – “diodontidae”.

The most common one found is the striped burrfish. The big boy of the group – the 2-foot porcupine fish – is rare in the northern Gulf and prefers the reefs of the open sea to grassbeds.

When threatened they will inflate with water (or air) and try to continue swimming. After the danger has passed, they will deflate and go about their merry way. There are stories about their flesh being poisonous and dangerous to eat – it is true. The compound they produce is one of the more toxic found in the fish world. Though there are certified chefs around the world who can safely clean them, it is not recommended you eat these.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 21, 2020

It’s Halloween…

The time of year we think of werewolves, warlocks, witches, and full moon evenings. But there is another creature who likes to howl at the moon this time of year – the coyote.

A coyote moving on Pensacola Beach near dawn.

Photo provided by Shelley Johnson.

Actually, coyotes howl all throughout the year, and they are not specifically howling at the moon. The name “coyote” is a Native American term meaning “singing dog”, or “barking dog”. They are famous for their early evening and early morning calls. Howls, barks, yelps, and yaps are very familiar to those living out west – and now for those living in the eastern United States.

It is believed the animal originated in the grasslands and deserts of the American southwest feeding on a variety of rodents. They have successfully dispersed across the country and can now be found in almost any habitat in the continental United States – including barrier islands. Though they owe much of their success to their ability to adapt to different foods and habitats, they also owe some of their success to humans. We have reduced their primary predators – bears, wolves, and mountain lions – to a level where they could move around more safely. There have been efforts to restore these predator populations in some localized areas of the U.S., but those are localized, and the process has been slow. All the while the coyote has enjoyed a more predator free world.

They are also opportunistic feeders. Though the bulk of their diet are small rodents, they are known to eat small birds, reptiles, amphibians, rabbits, squirrels, and even fruit. Out west, working in teams, they can take down larger prey – such as deer, and can do so here in the east as well. But their large prey targets are usually smaller members of the herd, sick, or old ones. They have also learned to feed on road kills of these animals.

Then there are humans. We provide an abundance of garbage which they have learned to scavenge through. Pet food left outside, gardens with produce, small livestock, and even pet cats and small dogs have been added to their menu. We have made their world much better.

With their numbers increasing in human populated areas, like Santa Rosa Island, people are becoming a bit nervous around them. The image of the toothed predator howling at the harvest moon on Halloween night in a pack with others makes us a bit uneasy. So, how dangerous are they?

Not very.

Coyotes are intelligent animals, and though they have learned to live and hunt within our neighborhoods, they are still afraid of us – they consider us trouble. On a recent trip to Colorado I was hiking down a trail and saw what appeared to be two sets of pointed ears in the grass. My guess was coyote but was not sure – so I began to walk towards them. Three coyotes immediately got up and moved off across the next ridge. They wanted nothing to do with me. And that is how it should be.

Those on barrier islands, like Santa Rosa, are no different. They are more active at dawn and dusk (crepuscular) and spend their days and late nights in a den somewhere. Occasionally people will see them in the middle of the day, or hear a yelp or howl around 2:00 AM, but it is more of a sunrise and sunset deal for them. They can remain motionless and undetected when people are around and will often run if we get too close. Many are not sure whether they are seeing a coyote or a German shepherd when they see one, both being about the same size. Coyotes tend to run with their tails down, unlike dogs and wolves who prefer to run with their tails up.

All of this said, there have been attacks on people – mostly out west and in southern California in particular. In most cases, the animals have either intentionally or unintentionally been fed by people. When this happens, they lose their fear of us and return for another easy meal. They are wild animals and being cornered by people or dogs (intentionally or unintentionally) can lead to defensive behaviors that could include attacks. To avoid this, we should not approach any coyote. Keep your trash secured and in cans that would be difficult for coyotes to access. Bring your pet food in at night and do not let pet cats and small dogs out in the evenings without supervision.

Bad encounters with these howling animals are rare, and with a little education and behavior changes on our part, should remain so.

Happy Halloween.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 16, 2020

When most people think of reefs, they think of the coral reefs of the Florida Keys and Australia. But here in the northern Gulf the winters are too cold for many species of corals to survive. Some can, but most cannot and so we do not have the same type of reefs here.

That said, we do have reefs. We have both natural and artificial reefs. There are natural reefs off Destin and a large reef system off the coast of Texas – known as the “Flower Gardens”. Here the water temperatures on the bottom are warm enough to support some corals. The artificial reef program along the northern Gulf is one of the more extensive ones found anywhere. There is a science to designing an artificial reef – you do not just go out and dump whatever – because if not designed correctly, you will not get the fish assemblages and abundance you were hoping for. But if you do… they will come.

Reefs are known for their high diversity and abundance of all sorts of marine life – including fishes. There are numerous places to hide and plenty of food. Most of the fish living on the reef are shaped so they can easily slide in and out of the structure, have teeth that can crush shell – the parrotfish can actually crush and consume the coral itself, and some can be fiercely territorial. There are numerous tropical species that can be found on them and they support a large recreational diving industry. Let’s look at a few of these reef fish.

Moray eel.

Photo: NOAA

Moray Eels

These are fish of legend. There all sorts of stories of large morays, with needle shaped teeth, attacking divers. Some can get quite large – the green moray can reach 8-9 feet and weigh over 50 pounds. Though this species is more common in the tropics, it has been reported from some offshore reefs in the northern Gulf. There are three species that reside in our area: the purplemouth, the spotted, and the ocellated morays. The local ones are in the 2-3 foot range and have a feisty attitude – handle with care – better yet… don’t handle. They hide in crevices within the reef and explode on passing prey, snagging them with their sharp teeth. Many divers encounter them while searching these same crevices for spiny lobster. There are probing sticks you can use so that you do not have to stick your hand in there. There are rumors that since they have sharp teeth and tend to bite, they are venomous – this is not the case, but the bite can be painful.

The massive size of a goliath grouper. Photo: Bryan Fluech Florida Sea Grant

Groupers

This word is usually followed by the word “sandwich”. One of the more popular food fish, groupers are sought by anglers and spearfishermen alike. They are members of the serranid family (“sea basses”). This is one of the largest families of fishes in the Gulf – with 34 species listed. 15 of these are called “grouper” and there have been other members of this family sold as “grouper”.

So, what is – or is not – a “grouper”. One method used is anything in the genus Epinephelus would be a grouper. This would include 11 species, but would leave out the Comb, Gag, Scamp, Yellowfin, and Black groupers – which everyone considers “grouper”. Tough call eh?

These are large bodied fish with broad round fins – the stuff of slowness. That said, they can explode, just like morays, on their prey. Anglers who get a grouper hit know it, and divers who spear one know it. They range in size from six inches to six feet. The big boy of the group is the Goliath Grouper (six feet and 700 pounds). They love structure – so natural and artificial reefs make good homes for them. They also like the oil rigs of the western Gulf.

An interesting thing about many serranids is the fact they are hermaphroditic – male and female at the same time. Most grouper take it a step further – they begin life as females and become males over time.

The king of finfish… the red snapper

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Snappers

The red snapper is king. Prized as a food fish all over the United States, and beyond, these fish have made commercial fishermen very happy. With an average length of 2.5 feet, some much larger individuals have been landed. This fishery put Pensacola on the map in the early 20th century. Sailing vessels called “Snapper Smacks” would head out to the offshore banks and natural reefs, return with a load, and sell both locally and markets in New York. There are large populations in Texas waters and down on the Campeche Banks off Mexico. “Snapper Season” is a big deal around here.

Though these are reef fish, snapper have a habit of feeding above, and away from, them. You probably knew there was more than one kind of snapper but may not know there are 10 species locally. Due to harvesting pressure, there are short seasons on the famous red snapper – so vermillion snapper has stepped in as a popular commercial fishery – and it is very good also. Some, like the gray snapper, are more common inshore around jetties and seawalls. Also known as the black snapper or mangrove snapper, this fish can reach about three feet in length and make a good meal as well.

The white grunt.

Photo: University of Florida

Grunts

Grunts look just like snapper, and probably sold as them somewhere. But they are a different family. They lack the canines and vomerine teeth the snappers have – other than that, they do look like snapper. Easy to tell apart right? Vomerine are tiny teeth found in the roof of the mouth, in snappers they are in the shape of an arrow. They get their name from a grunting sound they make when grinding their pharyngeal teeth together. A common inshore one is called the “pigfish” because of this. They do not get as large as snapper (most are about a foot long) and are not as popular as a food fish, but the 11 known species are quite common on the reefs, and the porkfish is one of the more beautiful fish you will see there.

Spadefish on a panhandle snorkel reef.

Photo: Navarre Beach Snorkel

Spadefish

This is one of the more common fish found around our reefs. Resembling an angelfish, they are often confused with them – but they are in a family all to themselves. What is the difference you ask? The dorsal fin of the spade fish is divided into two parts – one spiny, the other more fin-like. In the angelfish, there is only one continuous dorsal fin.

Spadefish like to school and are actually good to eat. It is also the logo/mascot of the nearby Dauphin Island Sea Lab.

Gray triggerfish.

Photo: NOAA

Triggerfish

“Danger Will Robinson!” This fish has a serious set of teeth and will come off the reef and bite through a quarter inch wetsuit to defend their eggs. Believe it – they are not messing around. Once considered a by-catch to snapper fishermen, they are now a prized food fish. They are often called “leatherjackets” due to their fused scales forming a leathery like skin that must be cut off – no scaling with this fish. They have the typical tall-flat body of a reef fish, squeezing through the rocks and structure to hide or hunt. We have five species listed in the Gulf of Mexico, but it is the Gray Triggerfish that is most often encountered.

Photo courtesy of Florida Sea Grant

Lionfish

You may, may not, have heard of this one – most have by now. It is an invader to our reefs. To be an invasive species you must #1 be non-native. The lionfish is. There are actually about 20 species of lionfish inhabiting either the Indo-Pacific or the Red Sea region.

#2 have been brought here by humans (either intentionally or unintentionally – but they did not make it on their own) – this is the case with the lionfish. It was brought here for the aquarium trade. There are actually two species brought here: The Red Lionfish (Pterois volitans) and the Devilfish (Pterois miles). Over 95% of what has been captured are the red lionfish – but it really does not matter, they look and act the same – so they are just called “lionfish”.

#3 they must be causing an environmental, and/or an economic problem. Lionfish are. They have a high reproductive rate – an average of 30,000 offspring every four days. There is science that during sometimes of the year it could be higher, also they breed year-round. Being an invasive species, there are few predators and so the developing young (encapsulated in a gelatinous sac) drift with the currents to settle on new reefs where they will eat just about anything they can get into their mouths. There have been no fewer than 70 species of small reef fish they have consumed – including the commercially valuable vermillion snapper and spiny lobster. There is now evidence they are eating other lionfish.

They quickly take over a reef area and some of the highest densities in the south Atlantic region have been reported off Pensacola. However, at a 2018 state summit, researchers indicated that the densities in our area have declined in waters less than 200 feet. This is most probably due to the harvesting efforts we have put on them. They are edible – actually, quite good, and there is a fishery for them. Derbies and ecotours have been out spearfishing for them since 2010. You may have heard they were poisonous and dangerous to eat. Actually, they are venomous, and the flesh is fine. The venom is found in the spines of the dorsal, pelvic, and anal fins. It is very painful, but there are no records of anyone dying from it. Work and research on management methods continue.