by Rick O'Connor | Jul 7, 2020

For many of the blogs we have posted on marine life of the Gulf of Mexico I have used the term “amazing” – but these cephalopods are truly amazing. There have been numerous nature programs featuring not just marine invertebrates but rather highlighting the cephalopods specifically. We have been amazed by their looks, their colors, their intelligence, and their ferocity. They are the animals of ancient mariner legends – the “kraken”.

These are not your typical mollusk. The elongated body and lack of external shell changes everything for cephalopods.

Photo: California Sea Grant

But for us who just visit the beach to play and walk – we rarely see them. They are quite common. The squid are almost transparent in the water column as they swim and usually run deep until nighttime. The only ones I have ever encountered were hauled up in shrimp trawls – but they are usually hauled up each time, and sometimes in great numbers. Octopus are more nighttime roamers as well. I have occasionally seen them diving during daylight hours, but they are very secretive and well camouflaged. I have found cephalopods both in the Gulf and within the estuaries – again, they are more common than we think.

A study conducted in the 1950s logged 42 species within the Gulf of Mexico. Many of them live in the open sea and at depths of 350-500 feet. There are actually four types of cephalopods – the octopus and squid we know, the cuttlefish and nautilus less so because they are not common in the Gulf region.

They are mollusk but differ from their snail and clam cousins in that they have very little, if any shell. The nautilus is an ancient member of this group and still possess an external shell. However, it is chambered and can be filled with gas like a hot air balloon allowing the nautilus to hover off the seafloor – something their snail/clam cousins can only dream about.

The squid and cuttlefish have reduced their shell to a surfboard looking structure that is found internally, serving almost like backbone. It allows them some rigidity in the water column, and they can grow to greater size. Actually, the squid are the largest invertebrates on the planet, with the “giant squid” (Architeuthus) reaching lengths of 50 feet or more.

The octopus differs from the squid in that it lacks a shell all together. Thus, it is smaller and lives on the ocean floor.

Photo: University of South Florida

The octopus lack a shell all together. Without this rigid bone within, they cannot reach the great size of the giant squid – so giant octopus are legend. However, there is a large one that grows in the Pacific that has reached lengths of 30 feet and over 500 pounds – big enough!

The lack of a shell means they must defend themselves in other ways. One is speed. With no heavy shell holding you down, high speed can be achieved. Again, squid are some of the fastest invertebrates in the ocean – being clocked at 16 mph. This may not outrun some of the faster fish and marine mammals, and many fall victim to them. Birds are known to dive down and eat large numbers of them. But they can counter this by having chromatophores. These are cells within the skin filled with colored pigments that they can control using muscles. This allows them to change color and hide. And their ability to change color is unmatched in the animal kingdom. I recommend you find some video online of the color change (particularly of the cuttlefish) and you will be amazed. Yes… amazed.

The chromatophores allow the cephalopods to change colors and patterns to blend in.

Photo: California Sea Grant

To control such color, they must have a more developed brain than their snail/clam cousins – and they do. The large brain encircles their esophagus and not only be used to ascertain the colors of the environment (and how to blend in) but also has the capability of learning and memory. The octopus in particular has been able to solves some basic problems – to escape, or get food from a closed jar, for example. Many of these chromatophores possess iridocytes – cells that act has mirrors and enhance the colors – again, amazing to watch.

All cephalopods are carnivorous and hunt their prey using their well-developed vision. Squid prefer fish and pelagic shrimp. Octopus are inclined to grab crustaceans and other mollusk – though they will grab a fish when the opportunity presents itself. Cephalopods hunt with their tentacles – which are at the “head end” of the body. The squid possess eight smaller arms and two longer tentacles. Each have a series of sucker cups and hooks to grab the prey. They keep their tentacles close to their bodies and, when within range, quickly extend them grabbing the fish and bringing back to the mouth where a sharp parrot-like beak is found. They bite chunks of flesh off and some have seen them bite the head off a mackerel. I was bitten on the hand by a squid once – one of the more painful bites I have ever had.

The extended tentacles of this squid can be seen in this image.

Photo: NOAA

The octopus does not have the two long tentacles – rather only the eight arms (hence its name). They move with stealth and camouflage (thanks to the chromatophores) sneaking up on their prey – or lying in wait for it to come close. Here things change a bit. Octopus possess a neurotoxin similar to the one found in puffer fish. They can bite the crab – inject the venom – which includes digestive enzymes similar to rattlesnakes and spiders – and ingest the body of the semi-digested prey after it dies. They can drill holes into mollusk shells and inject the venom within. Most will give a painful bite but there is one in the Indo-Pacific (the blue-ringed octopus) whose venom is potent enough to kill humans.

Making new octopus and squids involves the production of eggs. The male will deposit a sac of sperm called a spermatophore into the body of the female. She will then fertilize her eggs and excrete them in finger like projections that do not have hard shells. Squid usually die afterwards. Octopus will remain with the eggs – oxygenating and protecting them until they hatch. At which time they will die.

Though we have a variety of cephalopods near shore – the real grandeur is offshore. Out there are numerous species of bioluminescent cephalopods – most living at 500 feet during the day and coming within 300 feet at night. Many swim, while some float, others have developed a type of buoyant case they can carry their eggs in. Far too much to go into in a blog such as this one. I recommend you do a little searching and learn more about these amazing animals.

Enjoy the Gulf!

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 2, 2020

We have written about this guy before. The Cuban Treefrog is a potential threat to the Florida panhandle. According to EDDMapS, there are 13 records between Pensacola and Madison County. The records I am aware of are single individuals who appeared after the homeowner purchased landscaping plants (or flowers) from a local “box store”. In the last couple of weeks, I have again heard of two cases where individuals were found either at the “box store” garden center – or on their property after purchasing plants from such.

Image by Dr. Steve A Johnson 2005.

We all know that one individual does not a problem make. However, if multiple people continue to find them and they escape. Then eventually the numbers could get high enough where breeding populations could form. It is known that CTFs prefer to hang around humans and are not common in natural areas. So, this COULD make it easier for them to find each other over time and populations begin to establish themselves. We do not want this.

Why? What problem can a small frog cause?

Well, first – they are (as many invasive species are) aggressive consumers – feeding on local treefrogs to where their populations begin to decline. With that “space” left open, the invasive species quickly fills in and increases their populations. Over time you have a “monoculture” of CTFs and lower biological diversity within the local frog populations.

Is this a problem? Does it matter which frog is occupying the space?

It can. Lower biodiversity can make it difficult for frog populations to recover from environmental stress, such as changes in habitat, damage due to storms, changes in prey species. Lower biodiversity can make populations more susceptible to the spread of disease and the potential elimination of the species because no one in the population is genetically different enough so that there are those with resistant genes. Then there is the case as to whether the native frog predators will eat the invasive CTFs. They do have a strong enough toxin in their skin to cause allergic reactions in humans. This could be enough to keep the predators from eating. This will cause the CTFs populations to increase even more (classic invasive story – fewer predators) and the decline of native frog predators – some of which can directly, or indirectly, can have an economic impact on our community. So, yes – it can matter.

Second, CTFs are known to “hang out” in electrical panels. As many as 30 were found in one electric panel at the zoo in New Orleans. Inhabiting such places have been known to cause electrical problems, including short circuiting HVAC systems. We do not want this.

This Cuban Treefrog was found at the site of the building of a new home in the Pensacola area.

Photo: Keith Wilkins

Third, their calls have been described as “loud and sounding like a squeaky screen door”. This apparently drives some folks crazy. The noise is just too much. Of course, you would need a lot of CTFs to create such an unwanted serenade, but (reading above) you can see this could happen.

So, we would like to stop this before they become established, like the brown anoles and the lionfish.

What can we do?

First, be aware of what you are bringing home when you purchase landscaping plants from local vendors. Find out where their plants are grown and, if from the central/south Florida area, inspect the plant BEFORE you bring it home to make sure you are not bringing home anything else.

Second, if you find one – please consider reporting it. You can do this at www.EDDMapS.org. Log in (you will need a password – it is free) and report new sighting. If you get confused on how contact your local extension office and they can help walk you through it.

Get a photo if possible. We want to verify that it is a CTF and not one of the local native ones.

Cuban Treefrog

Photo: UF IFAS

How do you tell them apart?

First, it must be a treefrog. Treefrogs will have webbed feet but there are large toepads at the end of each toe so that it can cling to trees, and the side of your house.

Second, CTFs are much larger. Our native treefrogs will reach about 2”, CTFs can reach 5”.

Third, what if it is a small CTF? If you turn them over, you will see their skeleton through the skin – and it will appear blue – the native species are not blue.

Fourth, they have “warty” skin. Many of the natives will have smooth skin. The local cricket frogs will have warty skin, but they are smaller and have a triangle shaped dark spot on top of the head between the eyes – the Cuban Treefrog does not have this.

Fifth, they do not have stripes. They may be solid in color or have patches of darker areas. They can change color and have been seen as green, gray, brown, and even a light beige/white color.

Sixth, the skin between their eyes is fused to their skulls – not so in the native frogs.

Note: the CTF does produce a strong toxin through the skin. Though not deadly, it can be irritating to the skin and more so to the face. If you handle without gloves, you should not touch your face until you have washed well.

Third, educate your neighbors to let them know. Not just about the CTF but other potential invasive threats that could be hitchhiking up this way. With a community effort we should be able to keep them from establishing here.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 2, 2020

Cooters are one of the more commonly seen turtles when visiting a freshwater system. They are relatively large for a freshwater turtle (with a carapace about 13 inches long) and are often seen basking on logs, rocks, aerator pumps, you name it – and often in high numbers while doing so. They spook easy and usually leap into the water long before you reach them. But because of their beautiful smooth shells and large size, they can be seen from a distance – looking like wet rocks on a tree limb.

A “River Cooter” seen basking on a log in Blackwater River.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

They are in the genus Pseudemys (same as the Florida red-bellied turtles) and this genus is found throughout the southeastern United States. However, from there the breakdown of species becomes a bit challenging. There has been much debate how many species there really area, and how many are subspecies of those species. There are two distinct species for sure – the “River Cooter” (Pseudemys concinna) and the “Pond Cooter” (Pseudemys floridana). From here is gets a bit weird.

The “River Cooters” are just that – friends of rivers. They like those with a bit of a current, sand/gravel bottoms, basking spots, and grasses to eat. They have been found in estuaries, even with barnacles growing on them, so they have some tolerance for saltwater. River cooters can be distinguished from their “Pond Cooter” cousins in having a more aerodynamic shell (presumably for their habit of living in faster flowing rivers) with yellow-orange markings that form concentric rings on each scute (scale) of the carapace. Some of these seem to form a backwards “C”. Their plastron is yellow-orange but will have black markings along the margins of each scute.

This river cooter is basking on a log on the heads waters of the Choctawhatchee River in Alabama.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The “Suwannee Cooter” is believed to be a subspecies (Pseudemys concinna suwanniensis) found in tannic rivers from the Ochlockonee just west of Tallahassee south to the Tampa Bay region. It has only been found in rivers that flow into the Gulf of Mexico. A couple of records have been found in rivers flowing towards the Atlantic, but it is believed these were relocated by humans.

The “Eastern River Cooter” is found from the Ochlockonee River west to Mobile Bay – possibly as far as Louisiana. There has been a suggestion that the one west of Mobile Bay is the “Mobile Cooter” (Pseudemys concinna mobilensis) but the naming of this group, again, has been a bit crazy.

As mentioned, “Pond Cooters” are fans of slow-moving waters with muddy bottoms. Unlike river cooters, pond cooters will travel over land other than to lay eggs. Many of their “pond” selections dry up and they must find new habitat. Like river cooters, pond cooters feed on vegetation so aquatic plants are must and they also like to bask in the sun on logs with many cooters basking at once.

A pond cooter in a canal within the Gulf Islands National Seashore.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Physically they differ from river cooters in having a slightly domed shell near the head end. The yellow markings are not concentric, but rather are in straight lines and their plastrons are an immaculate beautiful yellow – with no markings on the margins. They do however have black circles on the bottom margins of their carapace. These are usually round with a small yellow spot in the center – resembling an “o”.

There is believed to be two subspecies of this group. Pseudemys floridana floridiana (the “Florida Cooter”) and Pseudemys floridana peninuslaris (the “Peninsula Cooter”). Told you it was all weird. The Florida cooter is found in the Florida panhandle and the Peninsula Cooter has been found all the way to the Florida Keys – though it does not seem to be common in the Everglades.

Add to the quagmire of species identification – there is hybridization between not only the types of pond and river cooters – but BETWEEN the pond and river cooters. So, if you live in the eastern panhandle where all of these seem to converge – just call them “cooters”!

They have an interesting nesting habit. When the females approach an open sunny sandy spot, she will dig a hole to lay about 20 eggs, but she will also dig two “satellite” nests on either side – and maybe place an egg or two in there. It is quite understood why they do this, but they do. They also may come to the beach up to five times in one year to lay eggs.

A pond cooter digging a nest on someone’s property.

Photo: Deb Mozert

Because of their high numbers and large size, this has been a favorite food item for humans for quite some time. Due to this, and the practice of shooting them off their basking spots, and alterations of river systems lower the habitat quality for the river cooters, their numbers have declined. The Suwannee Cooter in particular has been hard hit and is a species of concern. Due to this it no longer allowed to harvest them (or their eggs) from the wild. Because it is so hard to tell the Suwannee from other species/subspecies of cooters – ALL cooters are now protected by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission.

Another note – they do not eat fish. The young will eat worms and insects, but the adults are strictly herbivores. Many pond owners want to shoot them thinking they are eating the stocked fish by the landowner. They will not eat the fish – you are fine.

I think these are amazingly beautiful animals to see glimmering in the sunny on their basking logs as you explore our local rivers and wetlands. I hope you find them just as cool and appreciate them.

Resources:

Buhlman, K., T. Tuberville, W. Gibbons. 2008. Turtles of the Southeast. University of Georgia Press, Athens GA. 252 pp.

Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. Freshwater Turtles https://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/wildlife/freshwater-turtles/.

Meylan, P.A. (Ed.). 2006. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles. Chelonian Research Monographs No.3, 376 pp.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 26, 2020

This is a good name for this group. They are mollusk that have two shells. They tried “univalve” with the snails and slugs, but that never caught on – gastropods it is for them. The bivalves are an interesting, and successful, group. They have taken the shell for protection idea to the limit – they are COMPLETELY covered with shell. No predators… no way. But they do have predators – we will talk more on that.

An assortment of bivalves, mostly bay scallop.

Photo: Florida Department of Environmental Protection.

As you might expect, with the increase in shell there is a decrease in locomotion – as a matter of fact, many species do not move at all (they are sessile). But in a sense, they do not care. They are completely covered and protected. Again, we will talk more about how well that works.

The two shells (valves) are connected on the dorsal side of the animal and hinged together by a ligament. Their bodies are laterally compressed to fit into a shell that is aerodynamic for burrowing through soft muds and sands. Their “heads” are greatly reduced (even missing in some) but they do have a sensory system. Along the edge of the mantle chemoreceptive cells (smell and taste) can be found and many have small ocelli, which can detect light. The scallops take it a step further by having actually eyes – but they do live on the surface and they do move around – so they are needed.

The shells are hinged together at the umbo with “teeth like structures and the shells open and close using a pair of adductor muscles. Many shells found on the beach will have “scars” which are the point of contact for these muscles. They range is size from the small seed clams (2mm – 0.08”) to the giant clam of the Indo-Pacific (1m – 3.4 ft) and 2500 lbs.! Most Gulf bivalves are more modest in size.

Being slow burrowing benthic animals, sand and mud can become a problem when feeding and breathing. In response, many bivalves have developed modified gills to help remove this debris, and many actually remove organic particles using it as a source of food. Many others will fuse their mantle to the shell not allowing sediment to enter. But some still does and, if not removed, will be covered by a layer of nacreous material forming pearls. All bivalves can produce pearls. Only those with large amounts of nacreous material produce commercially valuable ones.

Coquina are a common burrowing clam found along our beaches.

Photo: Flickr

Another feature is the large foot, used for digging a burrowing in the more primitive forms. It is the foot we eat when we eat clams. They can turn their bodies towards the substrate, begin digging with their foot but also using their excurrent from breathing to form a sort of jet to help move and loosen the sand as they go – very similar to the way we set pilings for piers and bridges today.

These are the earliest forms of bivalves – the burrowers. Most are known as clams and most live where the sediment is soft. Located near their foot is a sense organ called a statocyst that lets them know their orientation in the environment. Most have their mantles fused to their shells so sand cannot enter the empty spaces in the body. To channel water to the gills, they have developed tubes called siphons which act as snorkels. Most burrow only a few inches, some burrow very deep and they are even more streamlined and elongated.

Some have evolved to burrow into harder material such as coral or wood. One of the more common ones is an animal called a shipworm. Called this by mariners because of the tunnels they dig throughout the hulls of wooden ships, they are not worms but a type of clam that have learned to burrow through the wood consuming the sawdust of their actions. They have very reduced shells and a very long foot.

This cluster of green mussels occupies space that could be occupied by bivavles like osyters.

Other bivalves secrete a fibrous thread from their foot that is used to grab, hold, and sometimes pull the animal along. These are called byssal threads. Many will secrete hundreds of these, allow them to “tan” or dry, reduce their foot, and now are attached by these threads. The most famous of this group are the mussels. Mussels are a popular seafood product and are grown commercial having them attach to ropes hanging in the water.

Another method of attachment is to literally cement your self to the bottom. Those bivalves who do this will usually lay on their side when they first settle out from their larval stage and attach using a fluid produced by the animal. This fluid eventually cements them to the bottom and the shell attached is usually longer than the other side, which is facing the environment. The most famous of these are the oysters. Oysters basically have lost both their “head” and the foot found in other bivalves. These sessile bivalves are very dependent on tides and currents to help clear waste and mud from their bodies.

Oysters are a VERY popular seafood product along the Gulf coast.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Then there are the bivalves who actually live on the bottom – not attached – and are able to move, or even swim. Most of these have well developed tentacles and ocelli to detect danger in the environment and some, like the scallops, can actually “clap their shells together” to create a jet current and swim. This is usually done when they detect danger, such as a starfish, and they have been known to swim up to three feet. Some will use this jet as a means of digging a depression in the sand they can settle in. In this group, the adductor has been reduced from two (the number usually found in bivalves) to one, and the foot is completely gone.

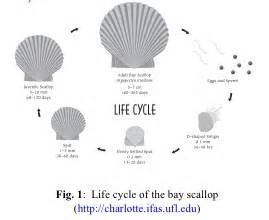

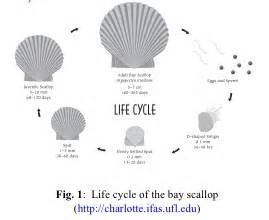

As you might guess, reproduction is external in this group. Most have male and female members but some species (such as scallops and shipworms) are hermaphroditic. The gametes are released externally at the same time in an event called a mass spawning. To trigger when this should happen, the bivalves pay attention to water temperature, tides, and pheromones released by the opposite sex or by the release of the gametes themselves.

Scallop life cycle.

Image: University of Florida IFAS

The fertilized eggs quickly develop into a planktonic larva known as a veliger. This veliger is ciliated and can swim with the current to find a suitable settling spot. Some species have long lived veliger stages. Oysters are such and the dispersal of their veliger can travel as far as 800 miles! Once the larval stage ends, they settle as “spat” (baby shelled bivalves) on the substrate and begin their lives. Some species (such as scallop) only live for a year or two. Others can live up to 10 years.

As a group, bivalves are filter feeders, filtering organic particles and phytoplankton as small as 1 micron (1/1,000,000-m… VERY small). In doing this they do an excellent job of increasing water clarity which benefits many other creatures in the community. As a matter of fact, many could not survive without this “eco-service” and the loss of bivalves has triggered the loss of both habitat and species in the Gulf region. Restoration efforts (particularly with oysters) is as much for the enhancement of the environment and diversity as it is for the commercial value of the oyster.

Now… predators… yes, they have many. Though they have completely covered their bodies with shell, there are many animals that have learned to “get in there”. Starfish and octopus are famous for their abilities to open tightly closed shells. Rays, some fish, and some turtles and birds have modified teeth (or bills) to crush the shell or cut the adductor muscle. Sea otters have learned the trick to crush them with rocks and some local shorebirds will drop them on roads and cars trying to access them. And then there are humans. We steam them to open the shell and cut their adductor muscle to reach the sweet meat inside.

It is a fascinating group – and a commercial valuable one as well. Lots of bivalves are consumed in some form or fashion worldwide. Take some time at the beach to collect their shells as enjoy the great diversity and design within this group. EMBRACE THE GULF!

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 18, 2020

Cooters are common freshwater turtles throughout the state of Florida. There are currently three species listed: Pseudemys concinna – commonly known as the “river cooter”, Pseudemys floridana – referred to as the “Florida cooter”, and Pseudemys nelsoni – the “Florida red-bellied turtle”. It is this third species we will focus on in this article.

The wide red markings contrasting with the yellow striping on the body makes this a beautiful turtle.

Photo: Wikipedia

When you pick up a Florida red-bellied turtle you will see why it gets that name. The belly, or plastron, is a reddish-orange color. You will also see red coloration of the large broad stripes on the carapace and small red spots on the marginal scutes of the carapace. Contrasting this with the brilliant yellow stripes of the head and legs – this a beautiful turtle.

Like other cooters, they are big pond turtles as well – reaching carapace lengths up to 15 inches. They have high domed shells, compared to the other two cooters, and the shell is much thicker. This is probably due to the fact that the Florida red-bellied lives with the American alligator. They are known to even lay their eggs in an alligator nest! Other features that separate them from their cousins is the presence of yellow striping between the eyes resembling an “arrow”, and a deep notch in the upper lip.

The distribution of this turtle is interesting. They are definitely found, and are common, in the peninsular part of the state – ranging from the Okefenokee Swamp in southern Georgia to the Florida Everglades. Here they most frequently found in slow moving backwaters of rivers and springs, lakes, ponds, marshes, sinkholes, and even canals along highways. However, there have been verified reports of this animal in the Apalachicola River basin. Several have been found on St. Vincent island between Apalachicola and Port St. Joe. One was photographed within the city limits of Apalachicola and a few in the Dead Lake region of the Chipola River feeding into the Apalachicola. There is about 100 miles between the Suwannee and Apalachicola River systems – how did they make this trip?

The red coloration of the common Florida Red-bellied turtle.

Photo: Flickr

One idea is that someone brought them there a long time ago – and they have survived. A long time meaning prior to the 1950s. Another thought is that the historic range may have included much of the Florida panhandle before sea level changed. There is an Alabama Red-bellied turtle (Pseudemys alabamensis) that inhabits the marshes of the Mobile Bay delta. The habitat here is very similar to the marshes of the Everglades, and the Apalachicola region. The Alabama red-bellied has very similar characteristics to the Florida red-bellied (arrow stripes and notch in upper lip). There are no records of the Alabama Red-bellied in the delta of the Escambia River, and no record of either species in the Choctawhatchee delta. So, who knows??? To add to the story – one Florida Red-bellied was verified in the Wacissa River – which lies about halfway between the Suwannee and the Apalachicola rivers. Yep… interesting mystery.

Like other cooters, the females are larger than the males and the males have elongated fingernails on their forelimbs to entice the female’s interest in mating. These long fingernails are also found on the sliders (Trachemys). In Florida, the red-bellied appears to breed year-round. Even though nesting is typical of other turtles (spring and summer) they may lay eggs year-round as well.

The females will approach the beach multiple times during the nesting season and lay anywhere from 6-30 eggs in the nest. Sex determination of the young is determined by the temperature within the nest, warmer eggs become females. The Florida red-bellied has an unusual habit of laying some of their eggs in alligator nests. Though alligators can be considered a predator of this turtle, sneaking in and laying eggs will provide protection – for unlike turtles, alligators guard their nests from predators. It is believed the thicker shell of the Florida red-bellied is to protect it from this possible adversary.

That said, they do have their predators. Like all young turtles there are a variety of birds, fish, mammals, and reptiles that feed on them. Red-bellies are plant eaters – feeding on a variety of aquatic plants including the invasive water hyacinth and hydrilla.

These are common basking turtles throughout much of peninsular Florida and visitors should easily get a glimpse of them while they are here. How far into the Florida panhandle they range is still a mystery – but an interesting one. I hope one day you get to see this beautiful turtle.

References

Buhlmann, K., T. Tuberville, W. Gibbons. 2008. Turtles of the Southeast. University of Georgia press, Athens GA. 251 pp.

Meylan, P.A. (Ed.) 2006. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles. Chelonian Research Monographs No.3. 376pp.