by Rick O'Connor | Jun 11, 2020

Well, maybe not…

But there could be reason to keep an eye out. We are not talking about the common ribbed or hooked mussels we found in the Pensacola Bay area. We are talking about an invasive species called the green mussel (Perna viridis).

The green mussel differs from the local species by having a smooth shell and the green margin.

Photo: Maia McGuire Florida Sea Grant

Why be concerned?

By nature, invasive species can be environmentally and/or economically problematic. In this case, it is more economic – which is unusual, most are more environmental concerns. The big problem is as a fouling organism. Like zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha), green mussels grow in dense clusters, covering intact screens to power plants, intact pipes to water plants, and can displace native spaces by competing for space. It has been determined they can grow to densities of 9600 mussels / m2 (that’s about 10 ft2) and they can do this on local oyster reefs – displacing native, and economically important, oysters. They grow quickly, being sexually mature in just a few months, and disperse their larva via the currents. To make things more interesting, they may be host to diseases that could impact oyster health.

So, what is the situation?

They are from the Indo-Pacific region, found all across southeast Asia and into the Persian Gulf. In this part of the world they are an aquaculture product. There was interest in starting green mussel aquaculture in China, and in Trinidad-Tobago. After they arrived in Trinidad, they were discovered in Venezuela, Jamaica, and Cuba – it is not believed this was due to re-locating aquaculture, but rather by larva dispersal across the sea… they got away.

This cluster of green mussels occupies space that could be occupied by bivavles like osyters.

It would be an easy jump from Cuba to Florida – and they came. The first record was in 1999 in Tampa Bay. They were found while divers were cleaning an underwater intake screen. Dispersal could have happened via larva transport in the currents, but it could have also occurred via ship ballast discharge at the port – this is how folks think it got there, they really do not know. From there they began to spread across the peninsula part of the state. They have been reported in 19 counties, most on the Gulf coast, and there is a record from Escambia County – however, that one was not confirmed.

How would I know one if I saw it?

They prefer shallow water and are often found in the intertidal zones – attached to pilings, seawalls, rocks. As mentioned, they grow in dense clusters and should be easy to find. They are long and smooth, with a mean length of 3.5 inches. There was one found in Florida measuring 6.8 inches, which they believe is a world record. Mussels differ from oysters in that they attach using “hairy” fibrous byssal threads – in lieu of cementing themselves as oysters do. As mentioned, the shell is smooth and may have growth rings, but it lacks the “ribbed” pattern we see on the local ribbed and hooked mussel. It will have a green coloration along the margin – hence its name, and the interior of the shell will be pearly white.

The shell at the far right is the common ribbed mussel native to our local salt marshes. Just to the left is the invasive green mussel. Can you tell them apart?

Photo: Maia McGuire Florida Sea Grant

They prefer salinities between 20-28‰, which would be the lower portions of the Pensacola Bay system (Santa Rosa Sound, Big Lagoon, maybe portions of Pensacola Bay). They are not a fan of cold water. They do not like to be in water at (or colder) than 60°F. Some biologist believe it is too cold in the panhandle for these bivalves, but we should report any we think may be them – to be sure.

What do we do if found?

1) Get a location and photos. Pull some off and get up close photos of an individual.

2) Report it. You can do this by contact the Escambia County extension office (850-475-5230 ext.111), or email me at roc1@ufl.edu.

3) If there is a method of removing all of them, do so. But this should be done only after the identification is verified. When removing try to collect all the shell material. The fertilized gametes within, if left, can still disperse the animal.

4) They are suggesting boat owners check their vessels when trailering. Avoid transporting them from one body of water to another.

5) I would recommend that marina owners do the same – check boats and pilings.

It appears the mean temperature of the Gulf is increasing. With this change it is possible some of the tropical species common in south Florida could disperse to our region, and that could include the green mussel. The most effective (and cheapest) way to manage an invasive species is catch them early and remove them before they can become established.

For more information on green mussels in Florida read https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/SG/SG09400.pdf.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 4, 2020

Recently there was a report of high fecal bacteria in a portion of Perdido Bay. I received a few concerned emails about the possible source. Follow up sampling from several agencies in both Florida and Alabama confirmed the bacteria was there, the levels were below both federal and state guidelines (so no advisory issued), and a small algal bloom was also found. It was thought the cause was excessive nutrients and lack of rain.

We hear this a lot.

Excessive nutrients and poor water quality.

What is the connection?

Many people understand the connection, others understand some of it, others still do not understand it. UF IFAS has a program called LAKEWATCH where citizen science volunteers monitor nutrients in some of lakes and estuaries within the state. Here in Escambia County, we have six such volunteers. Some of the six bodies of water have been monitored for many years, others are just starting now, but the data we have shows some interesting issues – many have problems with nitrogen. Let’s look closer.

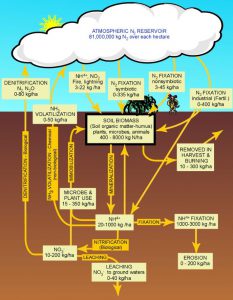

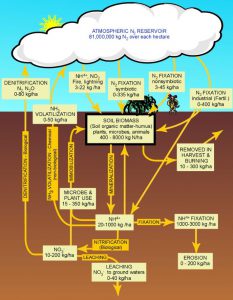

The nitrogen cycle.

Image: University of Florida IFAS

We have all heard of nitrogen. Many will remember from school that it makes up 78% of the air we breathe. In the atmosphere nitrogen is present as a gas (N2). It is very common element found in living creatures – as a matter of fact, we need it. Nitrogen is used to build amnio acids – which builds proteins – which is needed to produce tissue, bone, blood, and more. it is one of the elements found in our DNA and can be used to produce energy. However, it cannot do these in the atmospheric gas form (N2) – it needs to be “converted” or “fixed”.

One method of conversion is the weather. Nitrogen gas are two molecules of nitrogen held together by strong chemical bonds (N2). However, lightning provides enough energy to separate N2 and oxidize it with oxygen in the atmosphere forming nitrogen dioxide (NO2). This NO2 combines with water in the atmosphere to form nitric acid (HNO3). Which can form nitrates (NO3) with the release of the hydrogen and nitrate (NO3) is usable by plants as a fertilizer… a needed nutrient.

But much of the usable nitrates do not come from the atmospheric “fixing” of nitrogen via lightning. It comes from biological “fixing” from microbes. Atmospheric nitrogen can be “fixed” into ammonia (NH3) by bacteria. Another group of bacteria can convert ammonia into nitrite (NO2), and a third group can convert it from nitrite to the usable form we know as nitrate (NO3). Ammonia can also be found in the environment as a waste product of life. As we use nitrogen within bodies it can be converted into ammonia – which can be toxic to us. Our bodies remove this ammonia via urine, and many times we can smell this when we go to the restroom. Nitrogen fixing bacteria can convert this ammonia to nitrites as well and complete the nitrogen cycle.

Once nitrogen has been fixed to the usable nitrate it can be taken up by plants and used within. Animals obtain their needed nitrogen by eating the plants or eating the animals that ate the plants. In both cases, nitrogen is used for protein synthesis in our bodies and unused nitrogen is released into the environment to continue the cycle.

So, what is the connection to water quality?

You might think that excessive nitrogen (nutrients) in the water would be a good thing. Released ammonia, though toxic, could be “fixed” into nitrite and eventually nitrate and recycled back into life. And you would right. Excessive amounts of ammonia though, may not be converted quick enough and a toxic state could occur. We see this in aquaculture ponds and home aquaria a lot.

Members of the herring family are ones who are most often found during a fish kill triggered by hypoxia.

Photo: Madeline

But what about excessive nitrates? Shouldn’t that be good for the plants?

The concept makes sense, but what we see with increase plant growth in aquatic systems is problematic. Excessive plant growth can cause several problems.

1) Too much plant growth at the surface (algae, leafy vegetated material) can block sunlight to the other plants living on the bottom of the waterway. This can cause die off of those plants and a mucky bottom – but there is more.

2) Excessive plant growth at the surface and the middle of the water column can slow water flow. Reduced water flow can negatively impact feeding and reproductive methods for some members of the community, cause stagnation, and decrease dissolved oxygen – but there is more.

3) Plants produce oxygen, which is a good thing, so more plants are better right? Well, they do produce oxygen when the sun is up. When it sets, they begin to respirate just as the animals do. Here excessive plants can remove large amounts of dissolved oxygen (DO) in the water column at night. If the DO levels reach 3.0 µg/L many aquatic organisms begin to stress. We say the water is hypoxic (oxygen starving). When a system becomes hypoxic the animals will (a) come to the surface gasping, (b) some even approach the beach (the famous crab jubilee of Mobile Bay), (c) leave the water body for more open water, (d) die (a fish kill). This is in fact what we call a dead zone. Not always is everything dead, in many cases there is not much alive left – they have moved elsewhere so we say the bottom is “dead”. Here is something else… as the dead fish and (eventually) dead plants settle to the bottom they are decomposed by bacteria. This decomposition process requires dissolved oxygen – you guessed it – the DO drops even further enhancing the problem. In some cases, the DO may drop to 0.0 µg/L. We say the water is now anoxic (NO oxygen). I have only seen this twice. Once in Mobile Bay, and once in Bayou Texar. But I am sure it happens more often. The local environment can enhance (or even cause) this problem as well. Warm water holds less oxygen and much of the oxygen dissolved in water comes from the atmosphere – by way of wave action. So, on hot summer days when the wind is not moving much, and excessive nutrients (nitrogen) is entering the water, you have the perfect storm for a DO problem and possible fish kill.

4) Oh, and there is one other issue… some of the algae that produces these blooms release toxins into the water as a defense. These are known as harmful algal blooms (HABs). Red tide is one of the more famous ones, but blue-green blooms are becoming more familiar. So now you have a possible hypoxic situation with additional toxins in the water that can trigger large fish kills. Some of these HABs situations have killed marine mammals and sea turtles as well.

Though this process can occur naturally (and does) excessive nutrients certainly enhance them, and in some cases, initiate them. So, too much nitrogen in the system can be bad.

So, what does the LAKEWATCH data tell us about the Pensacola Bay system?

Well, first, we have not had volunteers on all bodies of water for the same amount of time. We currently have volunteers monitoring (1) northern Pensacola Bay, (2) Bayou Texar, (3) Bayou Chico, (4) Bayou Grande, (5) Big Lagoon, and (6) lower Perdido Bay. Pensacola Bay has JUST started, and Big Lagoon has not even started yet (COVID-19 issues) – so we only have data from the other four. Bayou Texar has the longest sample period at 13 years.

Lakewatch is a citizen science volunteer supported by the University of Florida IFAS

Second, this program does not sample for just nitrogen, but another key nutrient as well – phosphorus. When you look at a bag of fertilizer you will see a series of numbers looking like: 30-28-14. This would be nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium. People adding fertilizer to their lawns should know which nutrient they need the most and can by a fertilizer with a numerical concentration that is best for their lawn. You can have your soil tested at the county extension office. But the point here is that there is more than nitrogen to look at and, as we have learned, more than one form of nitrogen out there. So, what we do at LAKEWATCH is monitor for total nitrogen (TN) and total phosphorus (TP).

Another parameter monitored is total chlorophyll a (TC). The idea is… if there are excessive amounts of nutrients in the water there will be excessive amounts of algae. You could collect a sample of water and count the number of algal cells in the water – but another way is to measure the amount of chlorophyll in the water as a proxy for the amount of algae. Chlorophyll, of course, is the compound within plants that allows photosynthesis to happen. There is a chemical process used to release the chlorophyll within the cells and you can then use an instrument to measure the amount of chlorophyll in the water.

LAKEWATCH volunteers also monitor water clarity. It is true that clarity can be impacted by sediments in the water as much as an algal bloom, but anything that contributes to less sunlight reaching the bottom can be problematic for some bodies of water. This is done by lowering a disk into the water and measuring the depth at which it “disappears”.

For those not familiar with the term salinity, it is the measure of the amount of dissolved solids in the water – what most people say, “how salty is it?”. For reference, the Gulf of Mexico is usually around

35‰, most open estuaries are between 20-30‰.

Below is a table of the LAKEWATCH data we have as of the spring 2020.

| Year of Sampling |

Body of Water |

Total Phosphorus (µg/L) |

Total Nitrogen (µg/L) |

Total Chlorophyll (µg/L) |

Water Clarity (feet) |

Salinity (‰) |

| 2014 – 2018 |

Bayou Chico |

20-30 |

350 – 600 |

10 – 30 |

2.6 – 4.2 |

7.0 – 8.2 |

| 2012 – 2017 |

Bayou Grande |

16 – 19 |

320 – 340 |

5 -6 |

4.0 – 5.2 |

17 – 18 |

| 2007 – 2018 |

Bayou Texar |

17 – 18 |

600 – 800 |

6 – 8 |

3.4 – 3.8 |

8 – 10 |

| 2014 – 2018 |

Lower Perdido |

15 -16 |

350 – 360 |

5 -6 |

5.3 – 6.1 |

13 -14 |

| STATE AVG. |

(includes lakes) |

25.0 |

309 |

3.7 |

|

|

There are a couple of things that stand out right away

(keep in mind some water bodies have not been monitored very long by LAKEWATCH).

1) Phosphorus is not as big a problem in our part of the state. In the peninsula part of Florida there is a lot of phosphorus in the sediments and much of it is mined. You can see this in the average value for the state. Actually, because of this, many of the central and south Florida lakes are naturally high in phosphorus and this is not considered “polluted”. All that said, there are higher levels of phosphorus in Bayou Chico. Which is interesting. More on solutions in a moment.

2) We have a lot of nitrogen in our waters. Bayou Texar in particular is much higher than the state average. More on this in a moment.

3) We have a little more chlorophyll than the state average, but not alarming.

4) Bayou Grande and lower Perdido are clearer than Bayou’s Texar and Chico.

5) All these bodies of water are less than 20‰. More on this as well.

So, comments…

1) We already discussed the phosphorus issue (or non-issue), but what about Bayou Chico? Phosphorus is NOT introduced to the system from the atmosphere as nitrogen is – rather, it comes from the sediments. High levels of TP would suggest high levels of sediments in the water column (the water clarity data supports this) – which suggest high levels of run-off. The watershed for Bayou Chico is highly urbanized and run-off has historically been a problem.

2) Nitrogen can come from many sources, but when numbers get high – many will hypothesize they are most likely from lawn run-off (fertilizers), or sewage (septic leakage, sanitary sewage overflows, animal waste). There are certainly other possibilities, but this is where most resource managers and agencies begin.

3) Elevated chlorophyll indicates elevated primary production. This is not unusual for an estuary. They are known for their high productivity. Bayou Chico seems have more algae than the others. Most probably due to the increase levels of nutrients entering the watershed.

4) Bayou Grande and lower Perdido Bay have better water clarity than Bayou’s Chico and Texar. Though all four bodies of water have significant coastal and watershed development, Bayou’s Chico and Texar and completely developed as well as their “feeder creeks”. Again, indication of a run-off problem.

5) All four bodies of water have several sources of freshwater input as well as stormwater run-off that has contributed to the lower salinities found here. It is possible that the salinities here were less than 20‰ prior to heavy development.

Possible Solutions….

There is a common theme with each of these – stormwater run-off. Rain that historically fell on the land and percolated into the ground water, now flows off impervious surfaces (streets, driveways, parking lots, even buildings) into drainage pipes and discharges into the waterways. This stormwater carries with it much more than just fertilizers and animal waste, it carries pesticides, oil, grease, solid waste, leaf litter, and much more.

How do you reduce stormwater?

Well, there is not much you can do with impervious surfaces now, but the community should consider alternative materials and plans for future development – what we call “Green Infrastructure”. Green roofs, pervious streets and parking lots, there are a lot of methods that have been developed to help reduce this problem.

Another consideration is Florida Friendly Landscaping. This is landscaping with native plants that require little (or no) water and fertilizer. It also includes plants that can slow run-off and capture nutrients before they reach the waterways and methods of trapping run-off onto your property.

If you happen to live along a waterway, you might consider landscaping your property by restoring some of the natural vegetation along the shoreline – what we call a living shoreline. Studies have shown that these coastal plants can remove a significant amount of nitrogen from the run-off of your property as well as reduce coastal erosion and enhance fisheries by providing habitat.

Closed due to bacteria.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

What about sewage issues?

Unfortunately, most septic systems were not designed to remove nitrogen – so leaks occur and will continue. The only options you have there are (a) maintain your septic by pumping once every five years, (b) consider taping into a nearby sewage line.

Sewers systems are not without their problems. Sanitary sewage overflows do occur and can increase nitrogen in waterways. These are usually caused by cracks in old lines (which need to be replaced), are because we flush things down drains that eventually “clog the arties” and cause overflows. Things such as “flushable wipes”, which are flushable – they go down the drains – but they do not breakdown as toilet paper does and clog lines. Cooking grease and oil, and even milk have been known to clog systems.

Our LAKEWATCH volunteers will continue to sample three stations in each of their bodies of water. We are looking for a volunteer to monitor Escambia Bay. If interested contact me.

If you are interested learning more about green infrastructure, Florida Friendly Landscaping, or living shorelines lines contact your county extension office (850-475-5230 for Escambia County). If interested in issues concerning sanitary sewage overflows or septic issues, contact your county extension office, or (if in Escambia or Santa Rosa counties) visit ECUAs FOG website (Fats, Oils, and Grease) https://ecua.fl.gov/live-green/fats-oils-grease.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 2, 2020

They call it a slider…

Maybe because they slide off a tree trunks into the water? Honestly, I really don’t know – but sliders it is.

They are very common pond turtles all across the eastern and mid-west portions of the United States reaching as far west as New Mexico. Within this range there are two subspecies: The Yellow-bellied Slider (Trachemys scripta scripta) and the Red-Eared Slider (Trachemys scripta elegans). In Florida, only the yellow-bellied is native and it is only found in northern Florida. The red-eared slider is found throughout our state but is non-native and considered by some to be invasive.

The distinct yellow patch on the cheek helps identify the yellow-bellied slider.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Sliders are mid-sized emydid turtles and found in almost any type of water body. They prefer water bodies with slow currents, lots of sun, and plants – but have been found in retention ponds, rivers, golf courses, you name it. The shell (carapace) is rounder than the other common pond turtle called the cooter. Their shells are usually between 3 – 11 inches long, with females being larger. They have a slight keel running down the middle of their shell and the back margin is slightly “toothed” or serrated. The “belly” shell (or plastron) is usually yellow (source of their common name) as juveniles and forms dark blotches with age. The body is a dark green or black color with fine yellow stripes. The yellow-bellied slider will have a large yellow patch in the cheek area, which is easy to see from a distance. The red-eared has a small red patch behind and above the ear area. The carapace will be green as a juvenile and become darker as an adult. There will be beautiful patterns of yellow in the shell that fade with time. Older sliders will have faded shells all together and the yellow markings on the head and body will fade as well. They call this a melanistic phase.

Sliders are most active during daylight hours and are known to spend some time on land. They can be seen frequently basking on tree stumps and logs and can be aggressive towards each other. Red-eared sliders are known to be aggressive in aquaria.

They are omnivores. Young sliders are carnivorous feeding on small worms and insects. The adults switch to plant diet. Many sliders are shot, or destroyed in other ways, by locals thinking they will eat all the fish in their ponds – they will not.

Males are usually smaller, typically not having carapace lengths greater than 10 inches. Mature males will have extended “fingernails” or claws on their forelimbs. Mating takes place in the water and females have been known to travel up to 1500 feet from the water seeking good nesting habitat. Once found, they may dig a couple of “trial” nests before laying 5-20 eggs in a real one. They lay up to 3 active nests/nesting female/year.

Numerous animals will consume the turtle eggs and hatchlings. Adults have been consumed by alligators, minks, raccoons, otters, and gars.

Within their range, they are considered common but are still protected by Florida law. You may not have more than one slider/person/day from the wild and cannot use for commercial purposes. The red-eared slider is considered non-native and it is illegal to release non-natives into the local environment.

These are beautiful turtles and we hope that if you have not already seen one, you will get to soon.

by Rick O'Connor | May 27, 2020

As we continue our series on marine life in the Gulf of Mexico, we also continue our articles on marine worms. Worms are not the most charismatic creatures in the Gulf, but they are very common and play a large role on how life functions in this environment. Roundworms are VERY common. There are at least three phyla of them but here we will focus on one – the nematodes.

A common nematode.

Photo: University of Florida

Most nematodes are microscopic, a large one would be about 2 inches, and some beach samples have found as many as 2 million worms in 10 ft2 of sand. So, what do we know about them? What role, or function, do they play in the ecology of the Gulf of Mexico?

Well first, they are long and round – cylinder shaped. There is a head end, but it is hard to tell which end is the head. Round is considered a step up from being flat in that it can allow for an internal body cavity. An internal body cavity can allow for the development of internal body organs. Internal body organs can move large amounts of nutrients, blood, oxygen, and hormones around the body allowing the animal to become larger. Some argue that a larger body can have advantages over smaller ones. Some say the opposite, but either way – a large body has been successful for some creatures and an internal body cavity is needed for this.

That said, the nematodes do not have a complete internal body cavity. So, they do not have a complete assortment of internal organs. Being round reduces your efficiency in absorbing enough needed nutrients, oxygen, etc. through your skin alone and this MAY be a reason they are small. They are very small.

There are free living and parasitic forms in this group. There are at least 10,000 species of them, and they can be found not only in the marine environment, but also in freshwater and in the soil found on land. They have played a role in the success of agriculture, infesting both crops and livestock. Nematodes can be a big concern for farmers and gardeners.

The free-living forms are known to be carnivorous, feeding on smaller microscopic creatures. They have toothed lips, and some have a sharp stylet to grab or stab their prey. Some stylets are hollow and can “suck” their prey in. Moving through the environment, they can consume algae, fungi, and diatoms. Some are deposit feeders and others are decomposers. On our farms and in our gardens, they are known to enter plants via the roots and can be found in the fruit.

The life cycle of the human hookworm.

Image: CDC

The parasitic version of nematodes has been a problem for some species. In humans we have the hookworms and pinworms. Dogs have their heart worms. An interesting twist on the parasitic nematode way of life, compared to flatworms like tapeworms, is their lack of a secondary (or intermediate host). The entire life cycle can take place in the same animal.

Females are larger than males and fertilizations is internal. Males are usually “hooked” at the tail end and hold on to the females during mating. About 50 eggs will be produced and released into the digestive tract, where they exit the animal in the feces and find new hosts either by the feces being consumed or drifting in the water column.

There multiple forms of parasitism in nematodes.

– Some are ectoparasites (outside of the body) on plants.

– Some are endoparasites in plants – some forming galls on the leaves.

– Some infest animals but only as juveniles.

– Some live-in plants as juveniles and animals as adults.

– Some live-in animals as juveniles and plants as adults.

It would be fair to say that many forms of marine creatures have nematodes living either within them, or on them. Some can be problematic and cause disease; some diseases can be quite serious. Others play an important role in “cleaning” the ocean, filtering the sand of organic debris. Many have heard of nematodes but know little about them. Either good or bad, they do play roles in the ecology of the Gulf of Mexico.

by Rick O'Connor | May 17, 2020

In my time educating the public about Florida turtles I have found that most Floridians have not heard of diamondback terrapins. They have heard of, and seen turtles, but are not sure what the names of the different species are and are not familiar with the term terrapin at all. Which brings up the question – what is the different between a turtle, a tortoise, and a terrapin?

The light colored skin and dark markings are pretty unique to the terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Honestly, they are cultural terms and not “biological” descriptions. We associate the term “tortoise” with a land turtle – and this is true – yet we call the box turtle a “turtle” – which is fine. In Great Britain they call almost everything a “terrapin”. The term “terrapin” is a Delaware Indian term meaning “edible turtle”. Most turtles are edible, but this term stuck to a group of brackish water turtles in the Chesapeake area near Delaware we now call “terrapins”.

In the Mid-Atlantic states, terrapins are more known than they are here – and they appear to be more abundant. They are the mascot of the University of Maryland, and the official state reptile there. “Turtle Soup”, a popular cultural dish in the Chesapeake, is made with terrapins. It was served as part of the state dinner when Abraham Lincoln was president – considering it a classic “American” dish. They were harvested by walking through the marshes with a burlap sack and a gig. A sack could bring a harvester about $10, but when the popularity of the dish increased, hand harvesting could not keep up with demand and terrapin farms began. I know there were terrapin farms in the Carolinas, but there was one near Mobile, Alabama as well. Apparently, terrapins existed outside of the Chesapeake – and that brings us back to Florida… we have them too!

Ornate Diamondback Terrapins Depend on Coastal Marshes and Sea Grass Habitats

There are seven subspecies of this brackish water turtle. They range from Massachusetts to Texas. It is the only resident brackish water species, spending its whole life in salt marshes (or mangroves in south Florida). Florida has five of the seven subspecies, and three of the seven ONLY live in Florida – yet most of us do not know the animal exist.

Very few researchers worked with terrapins in this state – there was virtually nothing known about them in panhandle. In 2005 I began to survey panhandle marshes to see if terrapins existed here. I grew up in the panhandle, and like so many others, had never seen or heard of one. I asked local fishermen who use to gillnet the marshes back in the 1950s and 1960s (when it was allowed) if they were aware of this this turtle. I asked them “did you ever capture a terrapin?” They did not know what I was talking about. And then I showed them a picture… “OH… yea, we did catch these once in a while – what are they called again? Terrapins?”. This was a game changer for me in terrapin education – show them a terrapin and ask if they have ever seen a turtle that looks like this.

The response was still “what is that? It’s beautiful!”… and they are. Terrapins have light colored skin with dark specks or bars – a really pretty cool looking turtle. Oh, and they are in the panhandle, just not in big numbers – or, at least, we have not found them in big numbers 😊.

These brackish water turtles spend their entire lives in a marsh system feeding on mollusk and crustaceans. Like map turtles (their nearest cousins), the females are larger with wide heads for crushing the shells of their prey. They are considered an important member of the ecosystem in that the reduction of terrapins can cause an increase in the marsh periwinkle (a popular snail food) who would in turn stop feeding on leaf litter and attack the live plants themselves – threatening the existence of the marsh. So, they are important predators on marsh grazers. Not having a lot of trees in a salt marsh, you do not see them basking on logs as you do with other riverine turtles. They do, however, exit the water and bury in the mud/sand for long periods to bask.

A baby terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

After mating, the females usually leave the marsh for the open estuary, swim along the shorelines looking for high/dry ground for nesting. More often than not, these are sandy beaches – but they have been known to dig nest in crushed shell mounds, dredge spoil islands, along highways, backyards, and even runways of airports – wherever “high and dry” can be found in a marsh. In Louisiana a lady found one roaming around inside her outdoor shower – good luck nesting there!

The females lay about 10 eggs in a clutch and will lay more than one clutch each year. Baby terrapins are one of the coolest looking turtles you will see. They emerge from the nest in late summer and fall, hiding in the wrack debris along the shoreline. It is believed they actually have a more terrestrial life early on before entering the water and living out their lives in the marsh.

The popularity of turtle soup has waned since the Civil War, as have the wild harvest and aquaculture projects. However, the turtle is still under tremendous pressure from humans. We began using wired crab traps in the 1950s and terrapins have a habit of swimming into these, where they drown. The problem is not that large in Florida, but in the Chesapeake, they have found as many as 40 terrapins in one crab trap! Most of these are “ghost crab traps” – ones that “got away” from the owner but are still harvesting marine live – including crabs. One paper indicated that in the early part of the 21st century, in one year in the Chesapeake, over 900,000 blue crabs died in ghost crab traps – a commercial value of about $300,000. So, the ghost crab trap is a problem whether it kills terrapins, redfish, flounder, or blue crab. Today, many crab traps have biodegradable panels so that if the trap “gets away” it will eventually breakdown and not capture organisms like terrapins. In the Chesapeake many states require crab traps to have a By-Catch Reduction Device (BRD) to keep terrapins out – but allow crabs in. They are not required in Florida, however FWC will provide them for free if you are interested. I have some in my office in Pensacola and more than willing to give them to you. FWC also hosts crab trap removal programs, and I encourage you to participate in these.

This orange plastic rectangle is a Bycatch Reduction Device (BRD) used to keep terrapins out of crab traps – but not crabs.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

A bigger issue for Florida is the land-based predators. As we moved closer and closer to the salt marshes, we built bridges and roads that allowed land-based predators to reach the nesting beaches they previously did not have access to. Raccoons in particular are a big problem, depredating as many as 90% of the terrapin nests. Poaching for the pet trade is rising and FWC is working on this. Several major arrests have been made in Florida in recent years. It is illegal to sell Florida turtles, so do not buy them if you see them being sold somewhere. Report the activity to FWC.

Due to all of this, terrapins afford some form of protection in each of the coastal states where they exist. Some list them as “endangered” or “threatened”. In Florida, they do not have this label, but they are protected by FWC. No one is allowed to have more than two in their possession, and you are not allowed to have any eggs.

It is an amazing turtle. I currently conduct a citizen science program monitoring them in the western panhandle. I have a lot of eager volunteers wanting to see their first one in the wild. I hope they do soon. I hope they hang around long enough for everyone to see one in the wild.