by Rick O'Connor | Apr 7, 2020

These are some of the more familiar Florida turtles we have. Working with youth, I often hear them called “snapping turtles” because (a) these are the most common turtles they encounter, and (b) snapping turtles are the only name they know 😊

I myself had a “pet” box turtle when I was young named… “snappy”. Yep…

This Gulf Coast box turtle has a lot of yellow on the shell. Their shell coloration varies.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

That said, they do seem to be very common everywhere. Neighborhoods, parks, gardens, farms, you name it, people find these things. However, research suggests that the “commonness” of these guys maybe just in encounters with the same individuals, we really do not know how common they are.

They are a great way to introduce youth to the world of turtles. When picked up they quickly withdraw and close their shells – the only turtles we have that can completely do this (watch out though, they do have a habit of urinating when held).

There is debate as to how many kinds of box turtles we have. Most agree that the four that have been listed are all subspecies of Terrapene carolina. This turtle is typically called the “Eastern” box turtle. This species does exist and is quite common along the Atlantic seaboard. If differs from other subspecies in that the back end of the carapace ends abruptly – there is no “flare” to the margins of the carapace.

The lined pattern of this carapace identifies it as the Florida box turtle.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

What they do agree on is that two subspecies – the Florida box turtle (T. carolina bauri) does live in Florida – in the peninsular part of the state; and the Gulf Coast box turtle (T. c. major) does as well – in the panhandle. The two that are questionable are the Eastern box turtle (T. c. carolina) and the Three-toed box turtle (T. c. triunguis). As said before the Eastern definitely exists north of us but not sure whether it is in Florida. The Three-toed lives west of us but, again, not sure in Florida.

The Florida box turtle has a dark carapace with straight lined yellow streaks (like a sunbeam burst) pattern across its shell. The back end of the shell ends abruptly as it does in the Eastern. The Gulf Coast box turtle is the big boy of the group. Most of these box turtles have carapace lengths no more than 7 inches long. The Gulf Coast can be as long as 8 inches and the back-end margin of the carapace is flared. The pattern of color on the Gulf Coast varies. It can be red, yellow, brown and the lighter colored markings can be varied as well.

Box turtles are emydid turtles – which are usually associated with freshwater – but box turtles are much more terrestrial than their cousins. Some even referred to them as tortoises, but they are not. They like a variety of habitats being found in dry scrub pine forests, damp wet palm hammocks, and occasionally in marshes. Their hind feet are slightly webbed, but they are not great swimmers and are rarely found in deep water. That said, they do love rain. When it rains, they are on the move looking for food and places to lay eggs.

The abrupt downward end of the carapace and blotched pattern of the shell identifies this as an Eastern box turtle.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Research suggests that each turtle will inhabit about 5 acres and that a single acre can support up to 16 animals. They are omnivorous and eat a variety of invertebrates and plants – they particular like worms and snails. They have also been known to feed on dead animals lying about, – and this should make some folks happy… they like to eat cockroaches!

Males look different than females in that their plastron has a concaved depression in it and their tails are much longer. Females will usually lay about 2 eggs in a nest she digs during rainy afternoons. She will lay more than one nest each season usually producing about 9 eggs each year. Baby box turtles are usually dark brown with a yellow stripe running down the middle of their carapace.

Many turtles, eggs, and hatchlings are lost to predators. Fire ants are a big problem as are birds, mammals and reptiles. Scarlet snakes are particularly good at finding nests. Most adults’ bare scars from attacks but usually survive by withdrawing into their shells. One animal, the wild pig, is believed to be strong enough to crush the entire shell consuming the turtle. Raccoons are also good at grabbing a limb before they can withdraw – there are many 3-legged box turtles running around, but they seem fine and still hunt well.

Gulf Coast box turtle heading across an open field.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

One problem they do have is fire. They prefer wooded areas, even the flowerbeds around your house. They do not dig burrows like the gopher tortoise but rather make “forms” in the pine straw or leaves – where they spend the cold and hot days of the year – they also do not like low humidity days and will build forms during these times as well – but these do not protect them from fires, whether wildfires or prescribed ones.

Despite all of this – they are one of the longer-lived turtles in our state. Though most do not reach the age of 40 years these days, they have the ability to reach 100!

No doubt this is one of the coolest turtles we have – and we really enjoy encountering them. Take a walk around after a rainy day and see if you can find one in your yard!

References

Meylan P.A. (Ed). 2006. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles. Chelonian Research Monographs No.3, 376 pp.

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 5, 2020

We began this series on the Gulf talking about the Gulf itself. We then moved to the big, more familiar – maybe more interesting animals, the vertebrates – birds, fish, etc. In this edition we shift to the invertebrates – the “spineless” animals of the Gulf of Mexico. Many of them we know from shell collecting along the beach, others are popular seafood choices, but most we know nothing about and rarely see.

A spineless Comb Jelly.

Florida Sea Grant

They are numerous, on diversity alone – making up 90% of the animal kingdom. They may leave remnants behind so that we know they are there. They may be right in front of our faces, but we do not know what we are looking at. They are incredibly important. Providing numerous nutrient transport, and transfer, in the ecosystem – that would otherwise not exist. They also provide a lot of ecological services that reduce toxins and waste. One source suggests there are over 30 different phyla and over one million species of invertebrates. In this series we will cover six major groups and we begin with the simplest of them all… the sponges.

For some, you may not know that sponges are actually alive. For others, you knew this but were not sure what kind of creature it was. Are they plants? Animals? Just a sponge?

The answer is animal. Yea…

We usually think of animals as having legs, running around, eating things and defecting in places – the kinds of things that make good animal planet shows.

Sponges… would not make a great animal planet show. What are you going to watch? They appear to be doing nothing. They sit on the ocean floor… and… well… that’s it, they sit on the ocean floor. But they actually do a lot.

A vase sponge.

Florida Sea Grant

They are considered animal because (a) their cells lack a cell wall – which plants have, and (b) they are heterotrophic… consumers… they have to hunt their food and cannot make it as plants do.

What do they eat?

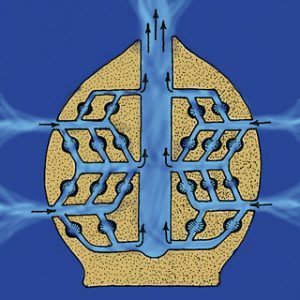

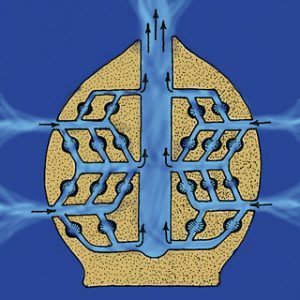

Plankton. Lots of plankton. Looking at a sponge you would call it one animal, but it is actually a colony of specialized cells working as a unit to survive. There are cells with flagella, called collar cells, that use these flagella to create currents that “suck” water into the body of the creature. This is how they collect plankton. The collar cells live in numerous channels throughout the sponge body connected to small pores all over the service of the sponge. This is where they get their phylum Porifera. As the water moves through the channels, the collar cells remove food and specialized cells called choanocytes release reproductive eggs called gemmules. All of the water eventually collects in a cavity, called the gastrovascular cavity where it exists the sponge through a large opening called an osculum.

This is how they eat and reproduce.

The anatomy of a sponge.

Flickr

The matrix, or tissue, of the sponge is held together by small, hard structures called spicules. It sort of serves as a skeleton for the creature. In different sponges the spicules are made of different materials, and this is how the creatures are divided into classes. Some are made of calcium carbonate, like seashells. Others are made of silica and are “glass-like”, and some made of a softer material called “spongin”, which are the ones we use to take baths with. Today purchased sponges are synthetic, not natural – but you can still get natural sponges.

Many sponges are tiny, others are huge. They all like seawater – not big fans of freshwater – and many produce mild toxins to defend the from predators. They do have predators though – hawksbill sea turtles love them. There is currently a lot of research going on using sponge toxins to kill cancer cells. Who knows, the cure to some forms of cancer may lie in the cavity of the sponge.

Another cool thing about them is that their cavities provide a lot of space for other small creatures in the ocean. Numerous species can be found in sponge tissue and cavities, utilizing this space as a habitat for themselves.

Florida Sea Grant

They are a major player in the development of reefs in the tropics and, like their counter parts coral, have experienced a decline due to over harvesting and harmful algal blooms. There are efforts in the Florida Keys to grow new sponge in aquaculture facilities and “re-plant” in the ocean. In the northern Gulf they are more associated with seagrass beds.

These are truly amazing creatures and the more we learn about them, the more amazing they become.

References:

Myriad World of the Invertebrates. EarthLife. https://www.earthlife.net/inverts/an-phyla.html.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 24, 2020

Article By: Whitney Cherry

4-H Agent Calhoun County

I know COVID-19 has been driving public and private discussion as of late. But, we have to stay vigilant in working against all public health threats. One of those threats we typically start talking about this time of year is mosquito borne illnesses and preventative mosquito control. Not only are mosquitoes pests, but they can transmit some pretty nasty diseases we wouldn’t want under normal circumstances. But with our healthcare system currently inundated with COVID-19 patients, we certainly wouldn’t want to unnecessarily add to the burden.

Adult female yellow fever mosquito, Aedes aegypti (Linnaeus), in the process of seeking out a penetrable site on the skin surface of its host.

Credit: James Gathany, Center for Disease Control Public Health Image Library Source: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/in792

So what’s the reality? While the incidence of mosquito borne illness is much lower with the advent of modern medicine and basic public practices of wearing bug spray and dumping or treating standing water, it’s definitely not unheard of. The Zika scare is not such a distant memory after all. And EEE (eastern equine encephalitis) was at an unusual high last year in horses in the panhandle. So what can we do?

With recent flooding in some areas and the weather warming, we can expect to see increasing populations of mosquitoes. Additionally, as the weather warms, we all tend to spend more time outside, increasing our likelihood of mosquito bites. Further exacerbating the situation is the widespread quarantine measures keeping many of us home. The late afternoon and early evening hours bring ideal weather to step outside and enjoy a little time away from TV and computer screens. We encourage fresh air and exercise outdoors, but we also encourage basic safety. So wear bug spray if you’re outside early morning and especially near, during, or shortly after dusk. Wear long sleeves and pants and socks if you can stand it. And keep standing water dumped out of containers on your property. If this isn’t possible, look for safe water treatment options. The most prevalent spreaders of disease (Aedes aegypti) actually require these containers of water to complete their lifecycle.

For more information on this or other Extension-related topics, call or email your local extension office.

Related information: http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/results.html?q=mosquito+borne+illness&x=0&y=0#gsc.tab=0&gsc.q=mosquito%20borne%20illness&gsc.page=1

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 20, 2020

As with mud turtles, full grown musk turtles are no bigger than your hand. They differ from mud turtles in that they have a single hinge on their plastron and the scutes just above that hinge are rectangular instead of triangular. Like mud turtles, they are very aquatic and not seen basking or out of water at anytime other than to lay eggs. Also like mud turtles, few people know they exist.

There are only two species in Florida, the Loggerhead Musk (Sternotherus minor) and the Common Musk (Sternotherus odoratus). There is a subspecies of the Loggerhead Musk in the far western panhandle, the striped-necked (Sternotherus minor peltifer).

Loggerhead Musk Turtle.

Photo: Flickr

The Loggerhead Musk is found through much of the southeastern United States and much of Florida. Like all musk and mud turtles it is small, with an average carapace length of 6 inches. The carapace will have 3 keels and small black flecks scattered across the light brown/olive colored shell. The head is large and wide with large jaws for crushing mollusk shells, a favorte food. The head is light colored with dark markings and 2 barbels (fleshy whiskers) under the chin. These barbels are chemosynthetic and help locate food. There are no striped on the head.

They prefer to walk across the bottom of either calm or flowing waterways, rarely leaving the water and have been found as deep as 44 feet into springs. In the waterways where they are found they have some of the highest densities of any turtle in the area – as much as 3000 individuals in a hectare. They breed in both fall and spring and the female usually does not travel far from the water to lay her eggs. Eggs have been found near logs and stumps. She will usually lay about 1-5 and they may take 100 days to incubate. Loggerheads feed on insects when young and switch to mollusk as adults. They have been known to eat other small turtles in captivity. They are preyed upon by alligator snapping turtles and maybe the alligator itself. They have been popular in the pet trade.

This common musk turtle (stinkpot) shows the dark head with stripes but also shows at bullet hole from a practice by some people called “plinking”. Where they practice shooting at turtles.

The Common Musk turtle is just that… common. It is found across the entire eastern portion of the United States and all of Florida. As its scientific name suggests (S. odoratus) it releases a pungent musk from glands near the bridge between the carapace and the plastron. This strong musk gives the turtle is other common name “Stinkpot”.

It too has a carapace about 6 inches long but differs from the Loggerhead in that its head is dark with 2 Yellow-White stripes running laterally. There is also a notch in the plastron near the tail. It is very aquatic, and can be found in high densities, but prefers still quite waters. They are known to be deep divers as well, diving to depths of 30 feet.

They will nest more inland than Loggerheads and usually lay multiple clutches of 1-9 eggs sometimes not burying them. Stinkpots are omnivorous, preferring mollusk but will also consume other invertebrates and seeds. Being small, they are preyed upon by raccoons, wading birds, fox, skunks, water snakes, hawks, eagles, alligators, snapping turtles, bull frogs, and even large mouth bass.

The handling of small turtles must be done with care. They have a long reach and nasty bite. But they are very cool turtles and very common. It is very cool to see them while snorkeling or paddling our rivers and springs.

Resource:

Meylan, P.A. (Ed.). 2005. Biology and Conservation of Florida Turtles. Chelonian Research Monographs No. 3, 376 pp.

by Rick O'Connor | Mar 9, 2020

When it comes to charismatic wildlife, there are few that are more than marine mammals. Everyone loves whales and dolphins. Even today, as many years as I have been working on the water, my colleagues and myself still get excited when we see dolphins. Seeing a whale is like a life-long bucket item. Marine mammals are pretty exciting to see.

A group of small dolphin leap from the ocean.

Photo: NOAA

In the world of marine mammals there are four different groups. Of course, there are the whales and dolphins (the cetaceans), there are the seals and sea lions (pinnipeds), the manatees (sirenians), and… believe it or not… the polar bear (ursids). But we only find two of these in the Gulf of Mexico. The polar bear, of course, does not live here. I know you needed to hear that from me. Pinnipeds no longer live here. Many may be surprised that there was once the Caribbean Monk Seal. There are records of this animal in the southern Gulf, but it is now extinct. There are records of California Sea Lions in the Gulf, possible release from some aquarium program – who knows, but no one has seen any in decades and it is believed they no longer exist here. So that leaves the cetaceans and the manatee.

The most recent publication (2017) states there are 28 species of cetaceans in the Gulf of Mexico. Cetaceans are subdivided into two groups: the baleen and the toothed whales. It is believed that 27 of the 28 species in the Gulf are toothed whales. Baleen whales are the big boys, 50-100’ in length and weighing tons. Some are the largest animals that ever existed on our planet. Most prefer cooler waters. Records of species come from whaling logs of the 19th and early 20th century as well as more recent scientific surveys and records from the Texas Marine Mammal Stranding Network. Early records suggest that right whales, humpbacks, sei, and even blue whales have been seen – though most of these were from the southern Gulf. But more recent science surveys indicated that only the Bryde’s Whale is encountered, and those are not common.

The majority are toothed whales. These would include the largest of them the sperm whale. Made famous in the novel Moby Dick, sperm whales were sought by whalers for their blubber and spermaceti. The blubber was boiled down to oil and used to light street lanterns and light houses. The spermaceti was used for a variety products including cosmetics. The sperm whales in the Gulf appear to be smaller than their counterparts in the open ocean and may be a separate subspecies. They seem to linger off the coast of Texas and Louisiana feeding on squid found at great depths.

The large head and double blowhole of a Bryde’s whale.

Photo: NOAA

Another toothed whale reported is the Orca, or killer whale. These are rare and are most often spotted in the central portion of the Gulf. There are numerous beaked whales and dolphins, but – though reported in early whaling logs – recent surveys suggest there are no porpoise. Porpoise differ from dolphin both in size and tooth shape. The most abundant dolphin is the pantropical spotted dolphin. Those who lived in the area in the 1980s and early 1990s might remember a stranding of dolphins that involved an adult female “Mango” and small baby named “Kiwi”. Mango died during recovery, but Kiwi lived for many years at the Gulfarium in Ft. Walton – these were pantropical spotted dolphins. The most familiar, and most often seen, are the Atlantic Bottlenose dolphins. These are a coastal species, many pods living within the estuary itself. They are the stars of many aquarium shows.

As you might guess, toothed whales are all carnivores. They only have canine teeth, so they must swallow their food whole. Their favorites are fish and squid. They have an amazing sense of echolocation that can help them navigate waters, detect prey, and even “stun” prey making it easier to eat. They give live birth as we do, and the calves stay with their mom for about two years learning how to survive. Cetaceans are very social forming groups known as pods. Most pods are dominated by females and young. Only one or two males are present.

A lone manatee spotted in Big Lagoon near Pensacola Pass. Sightings like these are becoming more common.

Photo: Marsha Stanton

Manatees are members of a group called Sirenia. This name comes from the fact that Columbus’ crew thought they were mermaids – “sirens of the sea”. It has been said before, that if they thought manatees were mermaids – their idea of a mermaid, and ours, is very different. That said, that is where they get their name. There are four species of sirenians on our planet, the one found here is the West Indian Manatee. They are found through the Caribbean, South Atlantic, and Gulf of Mexico. It is believed now that there are two subspecies – the Antillean of the Caribbean, and the Florida manatee from our neck of the woods. These are slow moving herbivores who can tolerate freshwater. They have a low tolerance for cold water and seek warm water springs, and the warm water discharges from power plants, during the winter.

Manatees are not as social as cetaceans and are usually not found in large groups unless they gather in warm water spots. Females usually give birth to a single calf which stays with her for about two years. They have flat molars, like cows, and feed on a variety of plants – the source of their other common name… “sea cows”. The numbers of these animals have increased in recent decades, but they are still low, and the animal is still protected. Boat strikes is one of the leading causes of death, though red tide, and cold stunning are also problems. Sightings of these animals in our area are increasing and we are currently tracking encounters at the county extension office. If you see one, please contact Rick O’Connor at the Escambia County Extension Office – (850) 475-5230, or roc1@ufl.edu.

Though the days of “Save the Whales” and “Save the Manatee” are not as common, these animals still face low numbers and problematic encounters with humans. Fishing gear, boat strikes, sounds, all take marine mammals in the Gulf each year. Hopefully we all get to check off seeing one of these magnificent creatures from our bucket list before the end of our time.

Resource:

Wursig, B. 2017. Marine Mammals of the Gulf of Mexico. In: Wards, C. (ed.) Habitats and Biota of the Gulf of Mexico: Before Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. Springer, New NY.