by Rick O'Connor | Aug 17, 2018

Being in the panhandle of Florida you may, or may not, have heard about the water quality issues hindering the southern part of the state. Water discharged from Lake Okeechobee is full of nutrients. These nutrients are coming from agriculture, unmaintained septic tanks, and developed landscaping – among other things. The discharges that head east lead to the Indian River Lagoon and other Intracoastal Waterways. Those heading west, head towards the estuaries of Sarasota Bay and Charlotte Harbor.

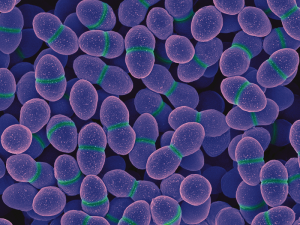

A large bloom of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) in south Florida waters.

Photo: NOAA

Those heading east have created large algal blooms of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria). The blooms are so thick the water has become a slime green color and, in some locations, difficult to wade. Some of developed skin rashes from contacting this water. These algal blooms block needed sunlight for seagrasses, slow water movement, and in the evenings – decrease needed dissolved oxygen. When the algae die, they begin to decompose – thus lower the dissolved oxygen and triggering fish kills. It is a mess – both environmentally and economically.

On the west coast, there are red tides. These naturally occurring events happen most years in southwest Florida. They form offshore and vary in intensity from year to year. Some years beachcombers and fishermen barely notice them, other years it is difficult for people to walk the beaches. This year is one of the worst in recent memories. The increase in intensity is believed to be triggered by the increase in nutrient-filled waters being discharged towards their area.

Dead fish line the beaches of Panama City during a red tide event in the past.

Photo: Randy Robinson

On both coasts, the economic impact has been huge and the quality of life for local residents has diminished. Many are pointing the finger at the federal government who, through the Army Corp of Engineers, controls flow in the lake. Others are pointing the finger at shortsighted state government, who have not done enough to provide a reserve to discharge this water, not enforced nutrient loads being discharged by those entities mentioned above. Either way, it is a big problem that has been coming for some time.

As bad as all of this is, how does this impact us here in the Florida panhandle?

Though we are not seeing the impacts central and south Florida are currently experiencing, we are not without our nutrient discharge issues. Most of Florida’s world-class springs are in our part of the state. In recent years, the water within these springs have seen an increase in nutrients. This clouds the water, changing the ecology of these systems and has already affected glass bottom boat tours at some of the classic springs. There has also been a decline in water entering the springs due to excessive withdrawals from neighboring communities. The increase in nutrients are generally from the same sources as those affecting south Florida.

Florida’s springs are world famous. They attracted native Americans and settlers; as well as tourists and locals today.

Photo: Erik Lovestrand

Though we are not seeing large algal blooms in our local estuaries, there are some problems. St. Joe Bay has experienced some algal blooms, and a red tide event, in recent years that has forced the state to shorten the scallop season there – this obviously hurts the local economy. Due to stormwater runoff issues and septic tanks maintenance problems, health advisories are being issued due to high fecal bacteria loads in the water. Some locations in the Pensacola area have levels high enough that advisories must be issued 30% of the time they are sampled – some as often as 40%. Health advisories obviously keep tourists out of those waterways and hurt neighboring businesses as well as lower the quality of life for those living there.

Then of course, there is the Apalachicola River issue. Here, water that normally flows from Georgia into the river, and eventually to the bay, has been held back for water needs in Georgia. This has changed flow and salinity within the bay, which has altered the ecology of the system, and has negatively impacted one of the more successful seafood industries in the state. The entire community of Apalachicola has felt the impact from the decision to hold the water back. Though the impacts may not be as dramatic as those of our cousins in south Florida, we do have our problems.

Bay Scallop Argopecten iradians

http://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/recreational/bay-scallops/

What can we do about it?

The quick answer is reduce our nutrient input.

The state has adopted Best Management Practices (BMPs) for farmers and ranchers to help them reduce their impact on ground water and surface water contamination from their lands. Many panhandle farmers and ranchers are already implementing these BMPs and others can. We encourage them to participate. Read more at Florida’s Rangeland Agriculture and the Environment: A Natural Partnership – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2015/07/18/floridas-rangeland-agriculture-and-the-environment-a-natural-partnership/.

As development continues to increase across the state, and in the panhandle, sewage infrastructure is having trouble keeping up. This forces developments to use septic tanks. Many of these septic systems are placed in low-lying areas or in soils where they should not be. Others still are not being maintained property. All of this leads to septic leaks and nutrients entering local waterways. We would encourage local communities to work with new developments to be on municipal sewer lines, and the conversion of septic to sewer in as many existing septic systems as possible. Read more at Maintaining Your Septic Tank – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2017/04/29/maintain-your-septic-system-to-save-money-and-reduce-water-pollution/.

And then there are the lawns. We all enjoy nice looking lawns. However, many of the landscaping plans include designs that encourage plants that need to be watered and fertilized frequently as well as elevations that encourage runoff from our properties. Following the BMPs of the Florida Friendly Landscaping ProgramTM can help reduce the impact your lawn has on the nutrient loads of neighboring waterways. Read more at Florida Friendly Yards – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2018/06/08/restoring-the-health-of-pensacola-bay-what-can-you-do-to-help-a-florida-friendly-yard/.

For those who have boats, there is the Clean Boater Program. This program gives advice on how boaters can reduce their impacts on local waterways. Read more at Clean Boater – https://floridadep.gov/fco/cva/content/clean-boater-program.

One last snippet, those who live along the waterways themselves. There is a living shoreline program. The idea is return your shoreline to a more natural state (similar to the concept of Florida Friendly LandscapingTM). Doing so will reduce erosion of your property, enhance local fisheries, as well as reduce the amount of nutrients reaching the waterways from surrounding land. Installing a living shoreline will take some help from your local extension office. The state actually owns the land below the mean high tide line and, thus, you will need permission (a permit) to do so. Like the principals of a Florida Friendly Yard, there are specific plants you should use and they should be planted in a specific zone. Again, your county extension office can help with this. Read more at The Benefits of a Living Shoreline – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2017/10/06/the-benefits-of-a-living-shoreline/.

Though we may not be experiencing the dramatic problems that our friends in south Florida are currently experiencing, we do have our own problems here in the panhandle – and there is plenty we can do to keep the problems from getting worse. Please consider some of them. You can always contact your local county extension office for more information.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 3, 2018

In recent weeks, the country has heard about shark attacks off the Carolina coast and great whites off the northern coast of the Gulf of Mexico – then of course, we just completed “Shark Week”. This sometimes makes visitors to our beaches a bit unnerved about swimming. Each year we hear about how other activities we engage in are much more dangerous than swimming in the Gulf where there are sharks – and this is true – but we may still have a concern in the back of our minds. So – we will give you some information that will hopefully enlighten you on the issue of sharks.

First, what kind of sharks are in the Gulf and how common are they?

According to Dr. Hoese and Dr. Moore from Texas A&M, there are 30 species of sharks who have been found in the Gulf of Mexico – and this includes the great white. They range in size from the Cuban Dogfish (3 ft.) to the whale shark (60 ft. in length). Each has their own niche. Some, like the large whale sharks, are plankton feeders. Others, like the blue and mako, are open ocean travelers covering large stretches of water hunting prey. Others, like the blacktip and spinner, are more common near shore – close to estuary outfalls where food is plentiful. And others still, like nurses sharks, are bottom dwellers feeding on slow fish and crustaceans.

The Bull Shark is considered one of the more dangerous sharks in the Gulf. This fish can enter freshwater but rarely swims far upstream. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

As far as how common they are – I was involved in shark tagging in the early 1980’s and we tagged several species. Blacktips and spinner sharks were very common. We also tagged a lot of bull and dusky sharks – though dusky sharks are declining. Tiger sharks were not as common at the time. It was believed this was due to an increase in shark rodeos in the 1970’s – which were popular during the “Jaws” films. However, those events stopped for several years and recent shark events have once again captured tigers. There are five species of hammerheads that were tagged – the scalloped and bonnethead were the most common. White sharks and makos are in the Gulf but were never tagged. It was believed they spent more time offshore (where we were not sampling). Both species have been seen closer to shore in recent years, but there are no reports of any problems from this. It is possible they have been doing this all along and were just undetected. Blacknose, finetooth, and silky sharks were also frequently tagged.

People are probably not surprised to hear that sharks frequent the bays. Many of the species mentioned above do so. The small (3 ft.) Atlantic sharpnose shark is one of the most common. Sawfish were once common in the estuaries but have declined significantly across the region to do over harvesting in the early 20th century. They are currently protected.

You have probably also read that bull sharks have been found in freshwater rivers – and this is the case. Some have been found several miles up river systems.

What type of prey do sharks prefer and how to do they select and hunt for them?

This, of course, varies from species to species. Plankton feeding whale sharks generally cruise slowly through the water column filtering small fish and crustaceans – the same as the great whales. They do tend to feeding in deeper water during the day and closer to the surface at night. They are following what is known as the Deep Scattering Layer. This is a large layer of zooplankton (animal plankton) that migrates each day – deeper (600 feet or so) during the daylight hours and closer to the surface in the evenings.

Bottom dwelling sharks feed on benthic creatures like flounder and crabs. Many have the ability to detect their prey buried beneath the sand using electric perception they have.

Many species of sharks are what we call “ram-jetters”. This means they do not have a pump system to pump water over their gills. So, in order to breath, they must swim forward. Swimming continuously requires a lot of energy. Most of them are what we call opportunistic feeders – meaning they will grab what they can. Stomach analysis of such sharks find primarily fish and squid, but other creatures have been found – such as birds and even other sharks. The general rule here is seek prey that is “easy”. If your objective in feeding were to obtain energy – it would not make since to chase prey that would require a lot of energy to catch. Simple first, and take opportunities when you can. It is the ram-jetter species that people are most concerned. Swimming and taking opportunities. However, evidence suggest that we are not a prey of choice, not good opportunities. More on this in a minute.

Tiger sharks are interesting. It is in their stomachs we find such things as hubcaps, metal, and other sorts of garbage. Because of their tooth design, they are also capable of eating sea turtles.

How often do shark attacks on humans actually occur and what were the people doing that may have enticed it to happen?

Records on human shark attacks are kept at the International Shark Attack File at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville, FL. This data set only logs unprovoked attacks – those where the people were doing their thing and all of a sudden… Not those where humans were pulling them into their boats after fishing or grabbing their tails while diving.

Blacktip sharks are one of the smaller sharks in our area reaching a length of 59 inches. They are known to leap from the water. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Based on this data – there have been 3031 unprovoked shark attacks reported worldwide since 1580 A.D. This equates to seven attacks / year. Granted… not all attacks are reported, particularly from the undeveloped regions of the world – and from early history, but it does give us something to look at.

Currently, we are averaging between 70 and 100 shark attacks worldwide and between 5-15 of these are fatal. Honestly, this is very low when compared to other activities in which humans participate.

| Year |

Deaths from Other |

Deaths from Shark Attacks |

| 1959 – 2010 |

Lightning strikes – 1970 |

26 |

| 2004 – 2013 |

Rip Currents – 361 |

8 |

| 2001 – 2013 |

Dog bites – 364 |

11 |

| 2000 – 2007 |

Hunting accidents – 441 |

7 |

| 2002 – 2013 (Florida only) |

Boating accidents – 782 |

2 |

As you can see… the risk is much lower.

It is true that most of the shark attacks worldwide are in the United States (46%) and that most in the U.S. are in Florida (56%). However, it is believed that this is due to the number of Americans (and Floridians) who enjoy water activities. In Florida, most of the encounters have been on the east coast – 89% of them! There have only been 65 attacks reported from the west coast – only 37 from the Florida panhandle – since 1580 A.D. There have only been six reported from Escambia County and one from Santa Rosa in that time.

As far as what people were doing when a shark attack occurred – most were surfing, but swimming has increased in recent years. This is believed to be connected to the increase in the number of humans swimming. The human population visiting beaches, particularly in the U.S., has increased significantly. Most shark attacks occur in near shore waters – which would make sense… that is where we are. Most are the “hit & run” version – meaning the shark hits the person and runs… not returning. Based on Florida reports, it is believed most of these are blacktips, spinners, and blacknose sharks. These rarely end in a fatality. “Bump & Bite” – meaning the shark circles, bumps the person, and then bites, are not as common. It is believed most of these are from great whites, tigers, and bull sharks. The few fatalities that happen are usually from this form of encounter.

Summary

When assessing “risk” in an activity you have to consider “control”. This means that the more you are in control of the situation, the less risky the activity seems to be. Most feel that in the water, the shark is in control – this increases our fear and risk concern. However, as mentioned in this article, many of the other activities we are involved – where we think we are in control – are far more risker than swimming on the open Gulf of Mexico.

However, shark attacks do occur and there are a few things swimmers can do to reduce their risk.

- Do not swim alone – all predators will try and isolate an individual from a group before they attack – much easier to attack an individual than a group

- Do not swim near dusk or after dark – to increase their chance of hunting success, sharks are more actively hunting in low light conditions

- Remove shiny objectives like jewelry – sunlight hitting metal objectives can appear to be baitfish to a shark

- Avoid blood in the water – it is true they have an excellent sense of smell – small amounts of blood in the water can be detected as far away as 100 feet suggesting easy prey nearby. Avoid swimming near fishing activity where bait and fish blood may be discharged into the water

I have been swimming in the Gulf all of my life. It is too much fun to worry about a low risk encounter with a shark. Follow the simple rules suggested by the ISAF and you should not have any problems.

Resources

The International Shark Attack File – https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/.

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana & Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. pp. 327.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 3, 2018

Of all the issues facing our local estuaries, high levels of fecal bacteria is the one that hinders commercial and recreational use the most. When bacteria levels increase and health advisories are issued, people become leery of swimming, paddling, or consuming seafood from these waterways.

Closed due to bacteria.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

I have been following the fecal bacteria situation in the Pensacola Bay system for several decades. Cheryl Bunch (Florida Department of Environmental Protection) has done an excellent job monitoring and reporting the bacteria levels, along with other parameters, for years – she has been fantastic.

The organisms used for monitoring have changed, so comparing numbers now and 30 years ago is somewhat difficult – but those changes came with good reason.

Fecal bacteria are organisms found in the large intestine of birds and mammals. They assist with digestion and are not a real threat to our health. Understanding that both birds and mammals in and near our estuaries must defecate, it is understandable that some levels of these bacteria are in the waterways. However, when levels are high there is a concern there are high levels of waste in the water. This waste can carry other organisms that can cause health problems for humans – such as hepatitis and cholera. So fecal bacteria monitoring is used as a proxy for other potential harmful organisms. No one wants to swim in sewage.

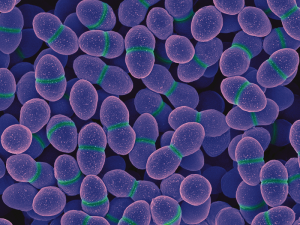

E. coli is a classic proxy for this type of monitoring and has been used for years. Recently it was found that saline water could kill some of the fecal bacteria – giving monitors’ low readings in estuarine systems – suggesting that there is little sewage in the water – when in fact there may be high levels of sewage undetected. They have found Enterococcus a better proxy for marine waters, particularly Enterococcus faecalis. Researchers have determined that a single sample of bay water should have more than 35 colonies of Enterococcus (ENT). If they find 35 or more colonies – a second sample is taken. If the counts are again high – a health advisory will be issued.

Over the last 30 years of monitoring FDEP’s reports on the Pensacola Bay area – there have been patterns. Most of the “hot spots” have been bayous and locations where rivers are discharging into an estuary. In addition, the periods of high fecal counts correspond well with periods of high rainfall. Locally, in the Pensacola Bay area, sampling has been reduced due to budget issues and some bodies of water are not sampled as often as others. Today both FDEP and the Florida Department of Health (FDOH) monitor and post their data via the Healthy Beaches Program. In this program, the sample stations are commonly used swimming areas – meaning some other locations are rarely, if ever, sampled. Based on these data, 30-40% of the samples from local bayous annually require a health advisory to be issued.

Health advisories can reduce interest in human related recreation activities, such as wakeboarding, paddling, or even fishing – and certainly impacts interest in swimming. Decades ago, swimming and skiing were very popular in local bayous. Today it is rare to see anyone doing so – most are motoring through heading to open bodies of water to spend their day. It may also be effecting property purchases. I have been contacted more than once with the question “would you buy on a house on XXX Bayou?”

Several local waterways are listed as impaired, and one is a BMAP area, due to high levels of bacteria. A BMAP (Basin Management Action Plan – read more at the link below) is a state designated body of water that is impaired (for some reason) and is required to make annual improvements to reduce the problem.

The spherical cells of the “coccus” bacteria Enterococcus.

Photo: National Institute of Health

So What Can We Do to Reduce This Problem?

In the Pensacola area, both the city and county have made efforts to modify and improve stormwater problems. Baffle boxes in east Pensacola have helped to reduce the amount of runoff entering the bayous and bays, thus reducing the frequency health advisories are being issued. That said, during heavy events the counts still increase – and rainfall seems to be increasing in the area in recent years. We will continue to monitor the frequency of advisories and post these on Sea Grant Notes through the Escambia County extension office each week.

From our side of the story (you and me) – anything you can do to reduce runoff will certainly help. Florida Friendly Landscaping techniques are a good start (see article on FFL posted below). Clean up after your pet, both in your yard and after walks – most people do… but not all. Septic systems have been a point of concern. If you have a septic system, maintain it (see article below on how). If the opportunity presents itself, you can move from septic to a sewer system. At many public places along the waterfront have signs asking everyone not to feed the birds. Congregating birds equals congregating bird feces and this can be a health issue.

Local and state governments are working to reduce the stormwater impacts on our local estuaries – which trigger other problems as well as high bacteria counts. Local residents and businesses can do the same.

References

Lewis, M.J., J.T. Kirschenfeld, T. Goodhart. 2016. Environmental Quality of the Pensacola Bay System: Retrospective Review for Future Resource Management and Rehabilitation. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. Gulf Breeze FL. EPA/600/R-16/169.

BMAP

https://floridadep.gov/dear/water-quality-restoration/content/basin-management-action-plans-bmaps.

Florida Friendly Landscaping

Restoring the Health of Pensacola Bay, What You Can Do to Help? – Florida Friendly Landscaping

http://blogs.ifas.ufl.edu/escambiaco/2018/06/08/restoring-the-health-of-pensacola-bay-what-can-you-do-to-help-a-florida-friendly-yard/.

Septic Systems

Maintain Your Septic Tank System to Save Money and Reduce Water Pollution

https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2017/04/29/maintain-your-septic-system-to-save-money-and-reduce-water-pollution/.

Septic Tanks: What You Should Do When a Flood Occurs

https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2018/05/04/septic-systems-what-should-you-do-when-a-flood-occurs/.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 6, 2018

The manatee may be one of the more iconic animals in the state of Florida. In Wyoming, we think of bison and bears. In Florida, we think of alligators and manatees. However, encountering this marine mammal in the Florida panhandle is a relatively rare occurrence… until recently.

Manatee swimming in Big Lagoon near Pensacola.

Photo: Marsha Stanton

For several years now, visitors to Wakulla Springs – in the eastern panhandle – have had the pleasure of viewing manatees on a regular basis. It is believed about 40 individuals frequent the river. Last year there were eight individuals that frequent the Perdido Key area, and a couple more were seen more than once near Gulf Breeze. This is not normal for us, but already this year one manatee has been spotted in the Big Lagoon area – so we may be seeing more as the summer goes on.

So what exactly is a manatee?

It is listed as a marine mammal, but frequents both fresh and saltwater habitats. Being mammals, they are warm blooded (endothermic). Maintaining your body temperature internally allows you to live in a variety of cold temperature habitats but water can really draw the heat quickly from anyone’s body. Marine mammals counter this problem by having a thick layer of fat within the skin – insulation called blubber. However, the manatees blubber layer is not very thick. So they are restricted to the tropical parts of the world and, in Florida, spend the winter near warm water springs. Many have learned the trick of hanging out near warm water discharges near power plants. In the warmer months, they venture out to find lush seagrass meadows in which to graze.

They are herbivores. Possessing flat-ridged molars for grinding plant material, they are more closely related to deer and cattle than the seal and walrus they look like. They lack canines and incisors, which deer and cattle use to cut the grass blades, but have large extending lips that grab and tear grasses with – very similar to the trunk of an elephant, which is their closest relative. Like many mammalian herbivores, they grow to a large size. Manatees can reach 15 feet in length and over 1000 pounds. They have two forearms that are paddle shaped and used for steering. The tail is a large circular disk called a fluke, which propels them through the water and is often seen breaking the surface. They are generally slow moving animals but can startle you when they decide to kick into “fourth gear” and burst across the river.

They are generally solitary animals, gathering in the wintertime around the warm springs. Males usually leave the females after breeding and do not form family units, or herds. Females are pregnant for 13 months and typically give birth to one calf, which stays with mom for two years. Like all mammals, the young feed on milk from mammary glands, but these glands are close to the armpits on the manatee. This makes it much easier for the calf to feed while both are swimming. This is not the case with dolphins and whales, where the mother must roll sideways to feed her young.

Manatees hanging out in Wakulla Springs.

Photo provided by Scott Jackson

There are three species of manatees in the world today. The Amazonian Manatee (Trichechus inunguis), the West African Manatee (Trichechus senegalensis) and the West Indie Manatee (Trichechus manatus). The Florida Manatee is a subspecies of the West Indian (Trichechus manatus latirostris). In the 1970’s it was estimated there were about 1000 West Indian manatees left in the word. Today, with the help of numerous nonprofits and state agencies, there is an estimated 6600 in Florida. Due to this increase, the manatee has moved from the federal endangered species list to threatened species. That said, human caused mortality still occurs and boaters should be aware of their presence. Since 2012, an average of 500 manatees die in Florida waters. Most of these are prenatal or undetermined, but about 20% are from boat strikes. Manatees tend stay out of the deeper channels, so boats leaving the ICW for a favorite beach or their dock should keep an eye out. Most of the time they are just below the surface and only their nostrils break for a breath of air. They usually breathe every 3-5 minutes when swimming but can remain below for up to 20 minutes when they are resting. Approaching a manatee is still illegal. Though their status has changed from endangered to threatened, they are still protected by state and federal law.

FWC suggest the following practices for boaters, and PWC, near manatees

- Abide by any speed limit signs – no wake zones

- Wear polarized sunglasses to aid in seeing through the water

- Stay in deeper water and channels as much as possible

- Stay out of seagrass beds – there is are numerous reasons why this is important, not just manatees

- If a manatee is seen, keep your boat/PWC at least 50 feet from the animal.

- Please do not discard your hooks and monofilament into the water – again, numerous reasons why this is a bad practice.

So Why are There More Encounters in the Florida Panhandle?

Good question…

Their original range included the entire northern Gulf coast. When their numbers declined in the 1960’s and 70’s there were fewer animals to venture this far north. Manatee sightings at that time did occur, but were very rare. Today, with increasing numbers, encounters are becoming more common. There is actually a Manatee Watch Program for the Mobile Bay area (https://manatee.disl.org/) and they have been seen as far west as Louisiana.

They are truly neat animals and to see one in our area is a real treat. Remember to view and photo, but do not approach. I hope that many of you will get to meet what maybe new summer neighbors.

Manatee swimming by a pier near Pensacola.

Photo: Marsha Stanton

References

2017 Manatee Mortality Data. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. http://myfwc.com/media/4132460/preliminary.pdf.

Florida Manatee Facts and Information. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. http://myfwc.com/education/wildlife/manatee/facts-and-information/.

Manatee Information for Boaters and PWC. Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. http://myfwc.com/education/wildlife/manatee/for-boaters/.

Manatee Sighting Network. https://manatee.disl.org/.

West Indian Manatee. Wikipedia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/West_Indian_manatee.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 6, 2018

This week’s article is a bit different… it is about nature we hope you DO NOT see – but hope you let us know if you do. Most of you know that Florida, along with many other states, continually battle invasive species. From Burmese pythons, to lionfish, to monitor lizards, we have problems with them all. Many of our invasive species are plants, which grow aggressively and take over habitats. They have few, if any, predators to control their populations and can cause environmental or economic problems for us.

The pretty, but invasive, beach vitex. Photo: Rick O’Connor

The best way to tackle an invasive species is to detect it when it first arrives and remove it as quickly as possible – this provides you the best chance of actually eradicating it from an area at the lowest cost. One such invasive plant that has recently invaded Escambia and Santa Rosa county beaches is Beach Vitex (Vitex rotundifolia).

Beach vitex is a vine that grows along the surface of sandy areas, like dunes. It has a main taproot from which the runners (stolons) extend in a radiating pattern, like a skinny-legged starfish. The stolons will develop secondary roots, which can form smaller deep root systems, and the entire maze of vines grows very quickly in the summer. The leaves are ovate, more round than elongated, and have a grayish-blue-green color to them – they tend to stand out from other plants. The plant can grow vertically to about three feet, giving it a bush appearance.

Another key characteristic for identification are the lavender flowers it produces, few other plants in our dunes do – so this is a good thing to look for. The flowers appear in late spring and summer. They are actually quite pretty. In the fall, the flowers are replaced by numerous large seeds, which form in clusters where the flowers were. These seeds are problematic in that they can remain viable for up to six months if they fall into the water – increasing their chance for dispersal.

So what is the problem?

In the Carolina’s this species was planted intentionally. They quickly learned of its aggressive nature and have had a state task force to battle it. The plant is allopathic – it can release toxins that kill neighboring plants allowing them to move into that space – this includes sea oats. Beach vitex has a taproot system, unlike the fibrous one of the sea oat, and cannot stabilize a dune as well – which is a problem during storms. In the Carolina’s there are numerous beach fronts where this is the only plant growing, a problem waiting to happen. Though there are no reports of it happening, it also has the potential to affect sea turtle nesting.

Beach Vitex Blossom. Photo credit: Rick O’Connor

So what do I do if I see it?

Contact us… You can contact me at roc1@ufl.edu, or call (850) 475-5230. Try to give us the best description of where the location is as you can. Many phones now come with an app that has a compass. This app also gives you your latitude and longitude. If your phone does not have this, again, give us the best description of the location you can. If you can include a photograph, that would be great. There are numerous other invasive species roaming our area, and you are welcome to report any you find to us. We hope to stay on top of these early arrivals and keep them under control.