by Rick O'Connor | Jul 10, 2015

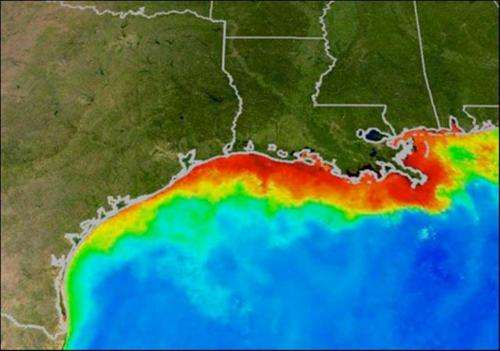

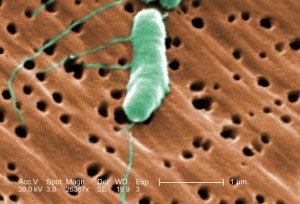

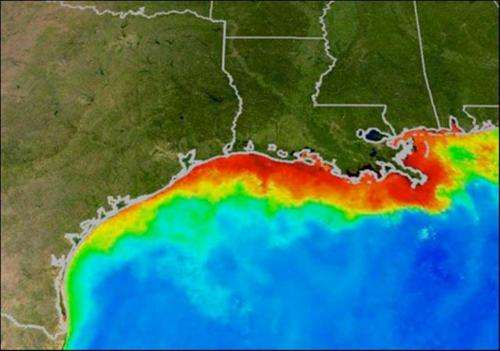

What is the Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone you ask? Well…it’s a layer of hypoxic water (low in dissolved oxygen) on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico. It was first detected in the 1970’s but reached its peak in size in the 1990’s. The low levels of dissolved oxygen decrease the amount of marine life on the bottom of the Gulf within this zone, including many commercially valuable species supporting the Gulf seafood industry.

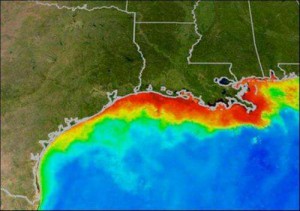

The red area indicates where dissolved oxygen levels are low.

What Causes this Dead Zone?

Drops in concentrations of dissolved oxygen within the water column can occur for a variety of reasons but is usually caused by one of two reasons. (1) Increasing water temperatures—as water temperature increases, its ability to hold dissolved oxygen decreases. (2) A process called eutrophication.

What is eutrophication?

Eutrophication is a process where an increase of nutrients in an aquatic system triggers an algal bloom of microscopic phytoplankton. These phytoplankton produce oxygen during the daylight hours but consume it in the evening. Once the bloom dies, decomposing bacteria begin to break them down and consume larger amounts of dissolved oxygen in doing so. When the dissolved oxygen concentrations drop below 2.0 mg/L we say the water is hypoxic and many marine organisms either begin to move out or die. The nutrients that trigger such blooms are primarily nitrates and phosphates. These can be introduced to the water column with plant and animal waste and with synthetically produced fertilizers we use on our fields and lawns. There is natural eutrophication, but when the process is triggered or accelerated by human activity we use the term cultural eutrophication.

So which is it; warming waters or eutrophication?

The Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone usually forms in spring and lasts through September. These are certainly the warmer months of the year, but the warmer waters are near the surface and much of the water column is not warm enough to cause this. Another point is that the Dead Zone is near Louisiana and there are warm locations in other parts of the Gulf where dead zones do not occur. However the Mississippi River does discharge near Louisiana. This river drains 41% of the continental United States, which contains 52% of the nation’s farms. The agricultural waste (plant, animal, and synthetic fertilizers) discharged into the Mississippi River contains nitrogen and phosphorus, the two key nutrients that trigger algal blooms. Based on this, most scientists agree that cultural eutrophication is the primary cause of the Gulf Dead Zone.

When they say it will be a “typical year”, what does that mean – what is a “typical year”?

Scientists from NOAA, the U.S. Geological Survey, and six partnering universities have released their annual forecast of the Dead Zone. The 2015 prediction has the area of the dead zone about equal to the size of Connecticut, which has been the average size for the past several years. This is what they mean by typical.

Can these dead zones occur in our area waters?

Yes, and they do. We do not typically call them “dead zones” but the same process occurs all over the world, including the bays of the Florida panhandle.

What can we do to reduce cultural eutrophication locally?

If you can do without fertilizing your lawn (or field), then do. If this is not an option then only put the amount of fertilizer required for your land/lawn. Most people over fertilize, which not only reduces water quality but is expensive for the property owners. If you can compost your plant waste, do so. With animal waste, please dispose of properly, in a manner where it not reach local waterways.

For more information on hypoxia, eutrophication, and solutions to reduce this problem, contact your county Extension office.

http://www.tulane.edu/~bfleury/envirobio/enviroweb/DeadZone.htm

http://www.iseca.eu/en/science-for-all/what-is-eutrophication

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/Phytoplankton/

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 10, 2015

After the recent report of a fatality due to the Vibrio bacteria near Tampa many locals have become concerned about their safety when entering the Gulf of Mexico this time of year. So what are the risks and how do you protect yourself?

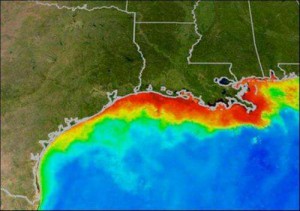

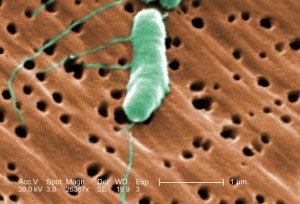

The rod-shaped bacterium known as Vibrio. Courtesy: Florida International University

What is the Flesh Eating Disease Vibrio?

Vibrio vulnificus is a salt-loving rod-shaped bacteria that is common in brackish waters. As with many bacteria, their numbers increase with increasing temperatures. Though the organism can be found year round they tend peak in July and August and remain elevated until temperature decline.

How do people contract Vibrio?

The most common methods of contact with Vibrio are entrance through open wounds exposed to seawater or marine animals and by consuming raw or undercooked shellfish, primarily oysters. The bacterium can also be contracted by eating food that is either served, and has made contact with, raw or undercooked shellfish or the juice of raw or undercooked shellfish.

What is the risk of serious health problems after contracting Vibrio?

Cases of Vibrio infection are rare and the risk of serious health problems is much higher for humans who are have a suppressed or compromised immune system, liver disease or blood disorders such as iron overload (hemochromatosis). Examples include HIV positive, in the process of cancer treatment, and studies show a particularly high risk for those with a chronic liver disease. The Center for Disease Control indicates that humans who are immunocompromised have an 80 times higher chance of serious health issues from Vibrio than healthy people. He also found that most cases involve males over the age of 40. According to the Center for Disease Control there were about 900 cases reported between 1988 and 2006; averaging around 50 cases each year. The Florida Department of Health reported 32 cases of Vibrio infections within Florida in 2014 with 7 of these begin fatal. Five of the cases were in the Florida panhandle but none were fatal. So far this year in Florida there have been 11 cases statewide, 5 of those fatal. Only 1 case was in the panhandle and it was nonfatal. Though 43 cases and 12 fatalities over the last two years in Florida are reasons for concern, when compared to the number of humans who enter marine and brackish water systems every day across the state, the numbers are quite low.

What are the symptoms of Vibrio infection?

For healthy people who consume Vibrio containing shellfish symptoms could include vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Wounds exposed to seawater that become infected will show redness and swelling. For the at-risk populations described above the bacteria will enter the bloodstream and rapidly cause fever and chills, decreased blood pressure, and blistering skin lesions. For these at-risk population 50% of the cases are fatal and death generally occurs within 48 hours.

It is important that anyone who believes they are at high risk and have the above symptoms that they seek medical attention as quickly as possible.

How can I protect myself from Vibrio infection?

We recommend anyone who has a chronic liver condition, hemochromatosis, or any other immune suppressing medical condition, not consume raw or undercooked filter-feeding shellfish and not enter the water if they have an open wound.

The Center of Disease Control recommends

- If harvesting or purchasing uncooked shellfish do not consume any whose shells are already open

- Keep all shellfish on ice and drain melted ice

- If steaming, do so until the shell opens and then for 9 more minutes

- If frying, do so for 10 minutes at 375°F

- Avoid foods served, and has had contact with, raw or poorly cooked shellfish or that has had contact with raw shellfish juice

- If shucking oysters at a fish house or restaurant, wear protective gloves

It is also important to know that the bacteria does NOT change the appearance or odor of the shellfish product, so you cannot tell by looking at them whether they are good or bad.

For more information on this bacteria visit:

http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/vibrio-infections/vibrio-vulnificus/

http://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/vibriov.html

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 20, 2015

This past week hundreds of dead fish washed ashore between Escambia and Okaloosa counties. Most were of one species but there were others who died and it appeared they had been in the water for quite a while. Determining the cause of fish kill can be tricky. You can observe how many different species were involved, and how many of each species. You can also review changes in the biological and chemical environment of the water system impacted. Fish kills occur for a variety of reasons but many are connected to either a decline in dissolved oxygen, the presence of red tide, or some pathogen that may be affecting the fish.

Dead fish near Ft. Pickens in Pensacola. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Excessive nutrients, many times associated with heavy rain, can trigger algal blooms that can eventually lower the concentration of dissolved oxygen; however high water temperatures can do the same. When dissolved oxygen levels drop below 4.0 mg/L most fish are stressed, and most fish leave. Some fish however are very sensitive to these changes and die, menhaden are one of them. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission listed menhaden as one of the species found on the beach but there were others as well, actually the majority were scaled sardines. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection monitors dissolved oxygen at the beach each week and their data indicated no problems prior to the kill. The Escambia County Division of Marine Resources measured the dissolved oxygen after the kill and found levels to be normal. Some would point to the abundant amount of green algae, “June grass”, as a sign of an algal bloom but mass amounts of June grass appear each summer and fish kills typically do not follow them.

Red tides are blooms of a particular microscopic single celled creature called Karenia brevis. When these photosynthetic protist are disturbed they can release a toxin which dissipates through the water and can become part of the aersols produced by waves. Many species of fish and marine mammals struggle with red tides and mortality due these outbreaks are common. Records of red tide blooms go back as far as the early colonial period and have been part of Florida for centuries. They typically form offshore and move inland with the wind and currents. Once they reach shallow waters human released nutrients can increase populations of K. brevis and enhance the problems they cause. They are more common in southwest Florida but do occur in the panhandle. Agencies along the Gulf coast monitor for red tide outbreaks each week. The Escambia County Division of Marine Resources does so here and found no traces of K. brevis before or after the kill.

As far as pathogens, or another possible cause, we are not sure. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has officially listed the cause as “unknown”. Fish kill data in Escambia County shows changes over the years. In the 1970’s there were a fewer fish kills reported each year but each kill involved hundreds of thousands of fish, many times menhaden. Today there are more fish kills reported but many of these reports are a single fish or fewer than 10. This is the first large number kill we have had in a while. Escambia County Sea Grant reports water quality information, including fish kills and red tides, for the Pensacola Bay area each week on their website (http://escambia.ifas.ufl.edu). Fish kill information for the state of Florida can be found at http://myfwc.com/research/saltwater/health/fish-kills-hotline/. If you have any questions about local fish kills contact Sea Grant at your local county extension office.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 5, 2015

For many who are seafood lovers there is nothing like a good grouper sandwich; makes me hungry just to write that. Groupers are members of the one of the largest families of fish in the Gulf of Mexico. There are 33 species in the family Serranidae, which include sea bass and perch, and many are sold as “grouper” in the seafood markets. There are 10 species of searranids that are in the genus Epinephelus and are considered the true groupers. One of these, Epinephelus itajara , is a monster; this is the Goliath Grouper.

Three goliath groupers over wreck in southwest Florida. Photo: Bryan Fluech Florida Sea Grant

As the name states, these fish can reach 6 feet in length and over 700 lbs. Goliath groupers are generally found on structure such as artificial reefs, near drill platforms, and on natural bottom. They tend to stay near the reefs they inhabit but will travel long distances for breeding. Data suggest that the highest concentrations of these fish are in southwest Florida but they disperse across the Gulf and along the Atlantic coast of south Florida. The large spawning aggregations occur offshore, generally from July through September, and the planktonic larva drift into the mangrove estuaries of southwest Florida. Here the young fish live for 5-6 years feeding on the abundance of food found there and then head back offshore searching for reefs to call their own. Many head to the northern Gulf and our area. Though they are large they feed relatively low on the food chain, consuming primarily crustaceans and slow moving reef fish.

They were a huge trophy fish back in the middle 20th century. Fishermen could not resist the chance to have a photograph with one of these behemoths. Because of this popular activity, and the loss of their mangrove nursery grounds due to development, their numbers diminished across the state and today there is a “no harvest” rule for the fish. However some divers are indicating their numbers are increasing and that the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission should to revisit the rule.

In response FWC’s research group, Fish and Wildlife Research Institute, in St. Petersburg conducts an annual “Goliath Grouper Count”. Modeled after the Christmas Bird Count conducted each year by the Audubon Society, the Goliath Grouper Count occurs during the first week of June. The counts have been occurring in south Florida for a couple of years but for the first time the panhandle will be participating this year. If you are a diver and interested there is a particular protocol that needs to be followed when counting. You can find out more by contacting Rick O’Connor in Pensacola at (850) 475-5230 or Scott Jackson in Panama City at (850) 764-6105 to obtain the protocol and the data sheets. The official count will run between June 1 and June 15.

by Rick O'Connor | May 29, 2015

This month there were many more plants flowering… it is true that April showers do bring May flowers. May not only brings more flowers but more tourists. Everyone is out enjoying the weather, including some wildlife. I was happy to include Florida Master Naturalist Paul Bennett on this hike and he was very helpful identifying plants. Thanks Paul!

Tent set up on Pensacola beach to protect from the sun. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Sign altering and educating folks that this is a sea turtle nest. Photo: Rick O’Connor

It is sea turtle nesting season all along the Florida Panhandle. The season begins in May and ends in October. This time of the season the females are heading up the beach looking for good nesting locations near dunes. There are five species of marine turtles that inhabit the northern Gulf and there are records of each species nesting here. They emerge at night and move towards the dunes where they excavate a deep cavity to lay about 100 eggs. The nest is covered and she returns to the water. The incubation period is between 60-70 days and the temperature of the nest determines the sex of the hatchling; the warmer eggs becoming females. It is illegal to disturb a sea turtle nest.

This tent was occupied when I was there but all too often they are left overnight so folks can return the same spot the following day. Tents and chairs are barriers for both nesting females and emerging hatchlings. If at all possible, remove these for the evening. In some counties it is required. Another problem is artificial lighting. Adult turtles are distracted, and many times abort the nesting activity due to bright lights. Most panhandle counties have a lighting ordinance that requires homes to use turtle friendly lighting. To learn more about the turtle friendly lighting program and local ordinances contact your county Sea Grant Agent at the local Extension office or visit http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/managed/sea-turtles/lighting/.

This county sign marks a public snorkel reef and also educates everyone about lionfish. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Mangrove seed washed ashore. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Summer means swimming and in many local counties there are interesting snorkel reefs nearby. We asked that everyone keep an eye out for the invasive lionfish as they enjoy their day. If one is spotted be aware they do have venomous, though not deadly, spines and please contact your local Sea Grant Agent at the county Extension office to let them know. If you are in Escambia County you can log your sighting at www.lionfishmap.org and FWC has a lionfish app for reporting; http://myfwc.com/news/news-releases/2014/may/28/lionfish-app/

The seed is of a red mangrove tree. These are common coastal plants in south Florida and elsewhere in the tropics. The red mangroves drops their seeds (propagules) into the water to drift in the currents to new locations. They frequently wash upon our shores and sometimes take root, but they do not last during our colder winters.

This Whitlow-Wort, also known as “square flower”. Common dune plant. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Track of an unidentified snake crossing a dune. Photo: Rick O’Connor

The flower to the left is the Whitlow-Wort, or as some locals call it… “square flower”. The track is of a snake but could not find it so I am not sure which species. The weather warms quickly here along the Gulf coast. A few months ago we may have been able to find this animal but with the increasing heat they were in a cool place somewhere. Snake encounters this time of year are typically at dawn and dusk.

The seed pod of a milkweed. Photo: Rick O’Connor

An open seed pod of a milkweed releasing seeds. Photo: Rick O’Connor

The milkweed bloomed a few months ago but here in May we find both the seed pods and, in the photo to the right, the “dandelion-like” seeds being released. This is one of the plants used by the migrating monarchs, which we should see later in the year.

Marsh Pink, a flower found in the wetter areas of the island.

Narrow-leaved Sagittaria. Another water loving plant.

Here are two of the many flowers we saw today. Both of these were found in the freshwater ponds located in the swale areas of the barrier island. The flower to the left is known as Marsh Pink. The one to the right is Narrow-leaved Sagittaria.

The yellow vine called “Love Vine”; correct name is Dodder.

It is good to see bees on the island.

This orange-yellow stringy vine is called “Love Vine” but there is not much love here; this is a parasitic plant called Dodder. This is the first we have seen of it this year and expect to see more. Many residents on the island believe it to be an non-native invasive plant but it is actually a native and quite common out there. I have also seen it in the north end of Escambia County.

We did see a few bees today and this is a good sign. There have been reports in recent years of the decline of our native bees and the impact that has had on gardening and commercial horticulture. In addition to seeing bees Paul and I also came across the famous yellow fly. These were encountered near the marsh on the sound side of the island. Loads of fun there!

The “bed” made by an unknown animal that has been frequenting this location all year. Photo: Rick O’Connor

This scat pile was near the location of the “bed” and along the drag marks made by this animal.

If you have been following this series since we began in January you may recall the strange “bedding” and drag marks we have encountered near the marsh (you can read other issues on this website). I have seen these drag marks, and apparent bedding areas, every month except last. I showed them to Paul and we are still not sure what is making them. Again, whatever it is seems to move from one body of water to another. We cannot find in foot tracks to help identify it… but we will!

The photo to the right is of a large scat pile approximately 15-16” across. It was relatively fresh and contained crab and shrimp shell parts. Not sure if it was left by the same animal that continually makes the drags but was in the same location so…

The pretty, but invasive, beach vitex. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Many of the plants on our barrier islands are blooming now, and so is this one. This is Beach Vitex (Vitex rotundifolia). It is an invasive/not-recommended plant. Currently we are only aware of 22 properties in Escambia County that have it. Sea Grant is currently working with the SEAS program at the University of West Florida to assist in removing them. If you believe you have this plant and would like advice on how to remove contact your local Sea Grant Agent at the county Extension office.

Let’s see what shows up in June!