by Sheila Dunning | Oct 16, 2020

That’s the question from a recent group exploring what washed up on the beach after Hurricane Sally.

Sea Cucumber

Photo by: Amy Leath

They have no eyes, nose or antenna. Yet, they move with tiny little legs and have openings on each end. Though scientists refer to them as sea cucumbers, they are obviously animals. Sea cucumbers get their name because of their overall body shape, but they are not vegetables.

There are over 1,200 species of sea cucumbers, ranging in size from ¾“ to more than 6‘ long, living throughout the world’s ocean bottoms. They are part of a larger animal group called echinoderms, which includes starfish, urchins and sand dollars. Echinoderms have five identical parts to their bodies. In the case of sea cucumber, they have 5 elongated body segments separated by tiny bones running from the tube feet at the mouth to the opening of the anus. These squishy invertebrates spend their entire life scavenging off the seafloor. Those tiny legs are actually tube feet that surround their mouth, directing algae, aquatic invertebrates, and waste particles found in the sand into their digestive tract. What goes in, must come out. That’s where it becomes interesting.

Sea cucumbers breathe by dilating their anal sphincter to allow water into the rectum, where specialized organs referred to as respiratory trees (or butt lungs) extract the oxygen from the water before discharging it back into the sea. Several commensal and symbiotic creatures (including a fish that lives in the anus, as well as crabs and shrimp on its skin) hang out on this end of the sea cucumber collecting any “leftovers”.

But, the ecosystem also benefits. Not only is excess organic matter being removed from the seafloor, but the water environment is being enriched. Sea cucumbers’ natural digestion process gives their feces a relatively high pH from the excretion of ammonia, protecting the water surrounding the sea cucumber habitats from ocean acidification and providing fertilizer that promotes coral growth. Also, the tiny bones within the sea cucumber form from the excretion of calcium carbonate, which is the primary ingredient in coral formation. The living and dying of sea cucumbers aids in the survival of coral beds.

When disturbed, sea cucumbers can expose their bony hook-like structures through their skin, making them more pickle than cucumber in appearance. Sea cucumbers can also use their digestive system to ward of predators. To confuse or harm predators, the sea cucumber propels its toxic internal organs from its body in the direction of the attacker. No worries though. They can grow them back again.

Hurricane Sally washed the sea cucumbers ashore so you could learn more about the creatures on the ocean floor. Continue to explore the Florida panhandle outdoor.

by Sheila Dunning | Jul 16, 2020

Credits: Clemson University, www.insectimages.org

The hickory horned devil is a blue-green colored caterpillar, about the size of a large hot dog, covered in long black thorns. They are often seen feeding on the leaves of deciduous forest trees, such as hickory, pecan, sweetgum, sumac and persimmon. For about 35 days, the hickory horned devil continuously eats, getting bigger and bigger every day. In late July to mid-August, they crawl down to the ground to search for a suitable location to burrow into the soil for pupation. While the hickory horned devil is fierce-looking, they are completely harmless. If you see one wandering through the grass or across the pavement, help it out by moving it to an open soil surface.

The pupa will overwinter until next May to early-June, at which time, they completely metamorphosize into a regal moth (Citheronia regalis). Like most other moths, it is nocturnal. But, this is a very large gray-green moth with orange wings, measuring up to 6 inches in width. It lives only about one week and never get to eat. In fact, they don’t even have a functional mouth. Adults mate during the second evening after emergence from the ground and begin laying eggs on tree leaves at dusk of the third evening. The adult moth dies of exhaustion. Eggs hatch in six to 10 days.

Adult regal moth, Citheronia regalis (Fabricius).Credits: Donald W. Hall, UF/IFAS

The regal moth, and its larvae stage called the hickory horned devil, is native to the southeastern United States. The damage they do to trees in minimal. Learning to appreciate this “odd” creature is something we can all do. For more information: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/IN/IN20900.pdf

by Sheila Dunning | Jul 3, 2020

Dog Star nights Astro Bob

The “Dog Days” are the hottest, muggiest days of summer. In the northern hemisphere, they usually fall between early July and early September. The actual dates vary greatly from region to region, depending on latitude and climate. In Northwest Florida, the first weeks of August are usually the worst. So, get out before it gets hotter.

In ancient times, when the night sky was not obscured by artificial lights, the Romans used the stars to keep track of the seasons. The brightest constellation, Canis Major (Large Dog), includes the “dog star”, Sirius. In the summer, Sirius used to rise and set with the sun, leading the ancient Romans to believe that it added heat to the sun. Although the period between July 3 and August 11 is typically the warmest period of the summer, the heat is not due to the added radiation from a far-away star, regardless of its brightness. The heat of summer is a direct result of the earth’s tilt.

Life is so uncertain right now, so, most people are spending less time doing group recreation outside. But, many people are looking to get outside Spending time outdoors this time of year is uncomfortable, potentially dangerous, due to the intense heat. So, limit the time you spend in nature and always take water with you. But, if you are looking for some outdoor options that will still allow you to social distance,

try local trails and parks. Some of them even allow your dog. Here are a few websites to review the options: https://floridahikes.com/northwest-florida and https://www.waltonoutdoors.com/all-the-parks-in-walton-county-florida/northwest-florida-area-parks/ Be sure to check if they are allowing visits, especially those that are connected to enclosed spaces.

Other options may include zoos and aquariums: www.tripadvisor.com/Attractions-g1438845-Activities-c48-Florida_Panhandle_Florida.html

Or maybe just wander around some local plant nurseries:

by Sheila Dunning | Dec 13, 2019

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.

Some North American breeding birds endure harsh winters; however, they are physically suited for cold environments in a number of ways. One, they are able to drop their metabolic rate to a near comatose state using very little energy. Two, they are able to position their feathers, or puff up, to trap heat generated by their own body. Others need to head to warmer climates.

Birds migrate for two reasons. Food and weather avoidance. North American breeding birds who nest in the northern part of the continent will migrate south for the winter. As winter approaches, insect and plant life diminishes in the snow-covered states. Migrating birds head south in search of food. Places like Florida are rich in insects, plant life, and nesting grounds.

Birds need high energy food to stay warm. Berry and seed producing plants contain proteins, sugars and lots of fats. Many native trees, shrubs and grasses can aid migratory and winter visiting birds in their relentless search for food. Gardening for birds and other wildlife enables an opportunity for people to experience animals up close, which providing an important habitat in the urban environment.

For more information on which plants are preferred by specific bird species go to: https://www.audubon.org/native-plants

For more information on landscaping for wildlife refer to: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/UW/UW17500.pdf

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 10, 2019

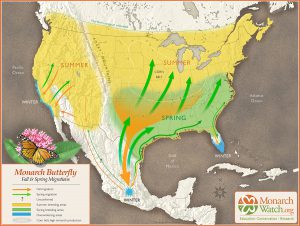

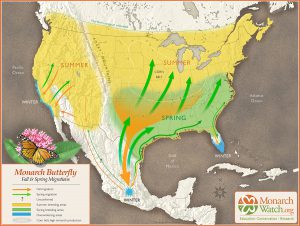

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

This spring, scientists from World Wildlife Fund Mexico estimated the population size of the overwintering Monarchs to be 6.05 hectacres of trees covered in orange. As the weather warmed, the butterflies headed north towards Canada (about three weeks early). It’s an impressive 2,000 mile adventure for an animal weighing less than 1 gram. Those butterflies west of the Rocky Mountains headed up California; while the eastern insects traveled over the “corn belt” and into New England. When August brought cooler days, all the Monarchs headed back south.

What the 2018 Monarch Watch data revealed was alarming. The returning eastern Monarch butterfly population had increased by 144 percent, the highest count since 2006. But, the count still represented a decline of  90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

Scientists estimate that 6 hectacres is the threshold to be out of the immediate danger of migratory collapse. To put things in scale: A single winter storm in January 2002 killed an estimated 500 million Monarchs in their Mexico home. However, with recent changes on the status of the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has delayed its decision until December 2020. One more year of data may be helpful to monarch conservation efforts.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

There is something more you can do to increase the success of the butterflies along their migratory path – plant more Milkweed (Asclepias spp.). It’s the only plant the Monarch caterpillar will eat. When they leave their hibernation in Mexico around February or March, the adults must find Milkweed all along the path to Canada in order to lay their eggs. Butterflies only live two to six weeks. They must mate and lay eggs along the way in order for the population to continue its flight. Each generation must have Milkweed about every 700 miles. Check with the local nurseries for plants. Though orange is the most common native species, Milkweed comes in many colors and leaf shapes.