by Sheila Dunning | Apr 14, 2018

Having just completed the Okaloosa/Walton Uplands Master Naturalist course, I would like to share information from the project that was presented by Ann Foley.

The Florida Torreya. Photo provided by Shelia Dunning

The Florida Torreya is the most endangered tree in North America, and perhaps the world! Less than 1% of the historical population survives. Unless something is done soon, it may disappear entirely! You can see them on public lands in Florida at Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravines Preserve and beautiful Torreya State Park.

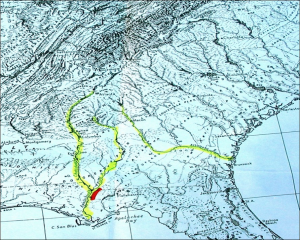

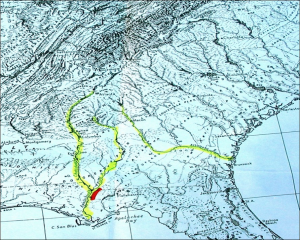

The Florida Torreya (Torreya taxifolia) is one of the oldest known tree species on earth; 160 million years old. It was originally an Appalachian Mountains ranged tree. As a result of our last “Ice Age” melt, retreating Icebergs pushed ground from the Northern Hemisphere, bringing the Florida Torreya and many other northern plant species with them.

The Florida Torreya was “left behind” in its current native pocket refuge, a short 40 mile stretch along the banks of the Apalachicola River. There were estimates of 600,000 to 1,000,000 of these trees in the 1800’s. Torreya State Park, named for this special tree, is currently home to about 600 of them. Barely thriving, this tree prefers a shady habitat with dark, moist, sandy loam of limestone origin which the park has to offer.

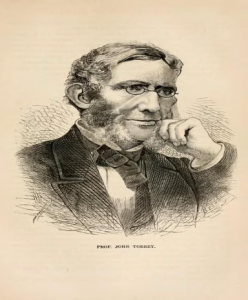

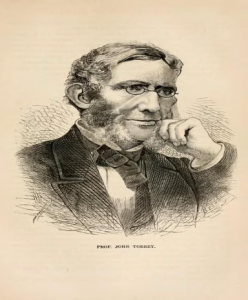

Hardy Bryan Croom, Botanist, discovered the tree in 1833, along the bluffs and ravines of Jackson, Liberty and Gadsen Counties, Florida and Decatur County in Georgia. He named it Florida Torreya (TOR-ee-uh), in honor of Dr. John Torrey, a renowned 18th century scientist.

Torreya trees are evergreen conifers, conically shaped, have whorled branches and stiff, sharp pointed, dark green needle-like leaves. Scientists noted the Torreya’s decline as far back as the 1950’s! Mature tree heights were once noted at 60 feet, but today’s trees are immature specimens of 3-6 feet, thought to be ‘root/stump sprouts.’

Known locally as “Stinking Cedar,” due to its strong smell when the leaves and cones are crushed, it was used for fence posts, cabinets, roof shingles, Christmas trees and riverboat fuel. Over-harvesting in the past and natural processes are taking a tremendous toll. Fungi are attacking weakened trees, causing the critically endangered species to die-off. Other declining factors include: drought, habitat loss, deer and loss of reproductive capability.

With federal and state protection, the Florida Torreya was listed as an endangered species in 1983. There is great concern for this ancient tree in scientific community and with citizen organizations. Efforts are underway to help bring this tree back from the edge of extinction!

Efforts include CRISPR gene editing technology research being done by the University of Florida Dept. of Forest Resources and Conservation- making the tree more resistant to disease. Torreya Guardians “rewilding and “assisted migration”. Reintroducing the tree to it’s former native range in the north near the Biltmore Estate in Asheville, NC, which has maintained a grove of Torreya trees and offspring since 1939 and supplying seeds for propagation from their healthy forest. Long before saving the earth became a global concern, Dr. Seuss (Theodor Seuss Geisel), spoke through his character the Lorax warning against urban progress and the danger it posed to the earth’s natural beauty. All of these groups, and many others, hope their efforts will collectively help bring this tree back from the brink!

by Sheila Dunning | Mar 2, 2018

Lantana is a landscape plant that easily escapes cultivation and spreads. Photo Credit: Jennifer Bearden

You know that plant in the corner of the yard that seems to be taking over? It’s the one that your friend “passed along” because they had plenty of them and wanted to share. After all, it grows so well. How can you go wrong?

The odds are that vigorous plant is a non-native species. The majority of what is sold in nurseries are introduced from a foreign country and developed for their uniqueness. The problem is that many of the plants brought into the United States arrive without their natural enemies. Under the long, warm growing season found in Florida, these non-native plants become the dominant plant in an area and manage to out-compete the native plants. When this happens, these introduced plants get labeled as an “invasive species”.

These invasive species threaten Florida’s environment, economy and health, requiring an estimated $120 billion a year to control them. Learning which of these plants have the potential to become invasive has been a focus of researchers with the UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. They have spent more than a year developing a searchable website and database to help Floridians assess problem non-native plants. The website features more than 800 species, is easily searchable by common or scientific name, and the results can be filtered. The site helps predict the invasive potential. Each species is categorized as “caution”, “invasive not recommended”, or “prohibited” based on their ecological threat.

If you want to learn more about your friend’s ”passalong” plant be sure to visit the Assessment of Nonnative Plants in Florida’s Natural Areas website and database. Also check the FLEPPC (Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council) list. Also make sure new plants are not on the Florida Noxious Weed List or the Federal Noxious Weed List.

by Sheila Dunning | Mar 1, 2018

An invasive plant is defined as a plant that is non-native to the ecosystem under consideration and whose introduction causes or is likely to cause economic or environmental harm or harm to human health (National Invasive Species Council, 2001). Research supports the fact that invasive plants damage natural areas, but there is great debate over which plants are invasive and where they are causing problems. Many lists of invasive plants have been complied by government agencies or environmental groups such as the Florida Exotic Pest Plant Council (www.fleepc.org) that include plants currently available at nurseries. Examples of such plants are Mexican petunia, Lantana and Porterweed.

Mexican Petunia

The bright color and rapid growth of Mexican petunia (Ruellia tweediana or R. brittoniana) has resulted in mass plantings that disrupt native wetland systems. The species is not used by butterflies, contrary to published misinformation. On the other hand, Porterweed is attractive to butterflies and the deep blue flower color of Stachytarpheta urticifolia has proven to be equally popular with gardeners. Additionally, Lantana camara is a favorite of Lepidoptera and a prolific bloomer, so hundreds of plants are installed in the landscape annually, spreading viable seed throughout the neighborhood and woods. Unfortunately, when it is found in natural areas it is difficult to distinguish the native lantana (L. depressa) from the invasive lantana (L. camara) and the two species can hybridize, making accurate identification even harder.

In fact, all three plants have native cousins with acceptable growth habits. Drought tolerant Ruellia caroliniensis has a pale violet-colored flower that serves as a host plant to the Buckeye butterfly. Stachytarpheta urticifolia is a low-growing groundcover with pale blue flowers. If the Porterweed is growing tall and upright, it is not the native. Leaf characteristics can be used to distinguish the native lantana (L. depressa) from the invasive lantana (L. camara). Native lantana has a tapered leaf base, whereas the invasive lantana has a truncate leaf base.

Lantana camara

Cultivars of species may have characteristics making them less invasive (Wood, 2007). University of Florida faculty has implemented an assessment process to evaluate non-native, highly utilized plants that are invading natural areas in Florida, including the marketed cultivars. The “UF-IFAS Assessment of Non-Native Plants in Florida’s Natural Areas” (IFAS Assessment) uses four criteria to categorize many of the plants available in the nursery trade. Over 700 species have been assessed (results are available at http://plants.ifas.ufl.edu/assessment/).

Some of the latest research included Lantana, Ruellia, and Stachytarpheta species. Each of them yielded a sterile cultivar that exhibited both the desired flowering of the invasive species while posing no threat to natural areas. When evaluated, these three cultivars scored well for minimal ecological impact, potential for expanded distribution, management difficulty and yet have a good economic value for the industry. So when looking for this year’s new garden introduction, one should consider ‘Purple Showers’ Ruellia, ‘Violacea’ Porterweed or ‘Patriot Cowboy’ Lantana. According to Dr. Gary Knox (UF/IFAS, North Florida Research and Education Center, Quincy, FL), they behaved well in the UF-IFAS assessment.

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 19, 2018

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.

The Florida Master Naturalist Program is an adult education University of Florida/IFAS Extension program. Training will benefit persons interested in learning more about Florida’s environment or wishing to increase their knowledge for use in education programs as volunteers, employees, ecotourism guides, and others.

Through classroom, field trip, and practical experience, each module provides instruction on the general ecology, habitats, vegetation types, wildlife, and conservation issues of Coastal, Freshwater and Upland systems. Additional special topics focus on Conservation Science, Environmental Interpretation, Habitat Evaluation, Wildlife Monitoring and Coastal Restoration. For more information go to: http://www.masternaturalist.ifas.ufl.edu/ Okaloosa and Walton Counties will be offering Upland Systems on Thursdays from February 15- March 22. Topics discussed include Hardwood Forests, Pinelands, Scrub, Dry Prairie, Rangelands and Urban Green Spaces. The program also addresses society’s role in uplands, develops naturalist interpretation skills, and discusses environmental ethics. Check the website for a Course Offering near you :http://conference.ifas.ufl.edu/fmnp/

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 19, 2018

We plant trees with the intention of them being there long after we are gone. However, m any trees and shrubs fail before ever reaching maturity. Often this is due to improper installation and establishment. Research has shown that there are techniques to improve survivability. Before digging the hole:

any trees and shrubs fail before ever reaching maturity. Often this is due to improper installation and establishment. Research has shown that there are techniques to improve survivability. Before digging the hole:

- Look up. If there is a wire, security light, or building nearby that could interfere with proper development as it grows, plant elsewhere.

- Dig a shallow planting hole as wide as possible. Shallow is better than deep! Many people plant trees too deep. A hole about one-and-one-half the diameter of the width of the root ball is recommended. Wider holes should be used for compacted soil and wet sites. In most instances, the depth of the hole should be LESS than the height of the root ball, especially in compacted or wet soil. If the hole was inadvertently dug too deep, add soil and compact it firmly with your foot. .

- Find the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk. If this is buried in the root ball then remove enough soil from the top so the point where the top-most root emerges from the trunk is at the surface. Burlap on top of the ball may have to be removed to locate the top root.

- Slide the plant carefully into the planting hole. To avoid damage when setting a large tree in the hole, lift the tree with straps or rope around the root ball, not by the trunk. Special strapping mechanisms need to be constructed to carefully lift trees out of large containers.

- Position the plant where the top-most root emerges from the trunk slightly above the landscape soil surface. It is better to plant a little high than to plant it too deep. Remove most of the soil and roots from on top of the root flare and any growing around the trunk or circling the root ball. Once the root flare is at the appropriate depth, pack soil around the root ball to stabilize it. Soil amendments are usually of no benefit. The soil removed from the hole and from on top of the root ball makes the best backfill unless the soil is terrible or contaminated. Insert a square-tipped balling shovel into the root ball tangent to the trunk to remove the entire outside periphery. This removes all circling and descending roots on the outside edge of the root ball.

- Straighten the plant in the hole. Before you begin backfilling have someone view the plant from two directions perpendicular to each other to confirm that it is straight. Break up compacted soil in a large area around the plant provides the newly emerging roots room to expand into loose soil. This will hasten root growth translating into quicker establishment Fill in with some more backfill soil to secure the plant in the upright position.

- Remove synthetic materials from around trunk and root ball. Synthetic burlap needs to be completely removed from the root ball; treated burlap can be left in place. String, strapping, plastic, and other materials that will not decompose and must be removed from the trunk at planting. Remove the wire above the soil surface from wire baskets before backfilling.

- Apply a 3-inch-layer of mulch. To retain moisture and suppress weeds cover the outer half of the root ball with an organic mulch. Do not cover the stem of the plant or the connecting root flare.

- Water consistently until established. For nursery stock less than 2-inches in caliper, this will require every other day for 2 months, followed by weekly 3-4 months. At each irrigation, apply 2 to 3 gallons of water per inch trunk caliper directly over the root ball. Never add irrigation if the ground is saturated.