by Thomas Derbes II | Dec 8, 2025

Aquaculture in North and South Carolina

North and South Carolina are next on our tour of aquaculture in the southern United States, and while they’re neighbors, their aquaculture stories couldn’t be more different. North Carolina is the undisputed trout powerhouse of the South, while South Carolina is just starting to reel in momentum of its own. From mountain streams to coastal waters, these bordering states offer two distinct climates, ecosystems, and approaches to aquaculture. Let’s take a closer look at how each one makes waves.

North Carolina

North Carolina’s aquaculture sector is a vital component of the state’s agricultural and coastal economies. The industry encompasses both freshwater and marine operations, ranging from small family-owned farms to larger commercial enterprises. North Carolina’s diverse climate and water resources support a variety of aquaculture activities, including food fish production, shellfish farming, and ornamental species cultivation.

Besides the typical aquacultured finfish species (catfish, tilapia, and hybrid striped bass), North Carolina is a leader in Rainbow Trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) aquaculture in the South. Rainbow trout farms are found primarily in the western mountainous region of North Carolina, allowing farmers easy access to very cold, clean water. Rainbow trout are typically raised in a flow-through raceway system. A flow-through raceway aquaculture system is a setup where fresh, oxygen-rich water continuously flows through long, narrow tanks (raceways) that hold the fish. One interesting statistic is that even though 13 farms left the industry, the value of the crop increased (see chart below).

Bobby N. Setzer State Fish Hatchery – Carolina Outdoor Guide

North Carolina also has an up-and-coming Eastern Oyster (Crassostrea virginica) aquaculture industry. N. Sea. Oyster Company is an oyster farm located in the beautiful waters of Topsail Sound. One of their claims to fame is their “Divine Pines of Topsail Sound.” These oysters are a rare delicacy that can only be found in certain parts of the world during a certain time of the year. The gills of the oyster become bright green due to the presence of a blue-green diatom in the water that the oyster consumes, and the taste changes as well (Green Gilled Oysters).

North Carolina is supported by several key institutions advancing aquaculture research, education, and industry development. North Carolina State University (NCSU) leads studies in fish health, nutrition, and production, while the University of North Carolina Wilmington (UNCW) contributes expertise in marine aquaculture, shellfish biology, and coastal ecosystem management. North Carolina Sea Grant complements these efforts by providing research, education, and outreach focused on aquaculture innovation, sustainability, and business development, and the North Carolina Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services supports industry growth and regulatory compliance through its Aquaculture Division.

| North Carolina Aquaculture |

| Category |

2017 Farms |

2017 Value* |

2023 Farms |

2023 Value* |

+/- Farms |

+/- Value |

| Catfish |

31 |

$4,462 |

16 |

$2,031 |

-15 |

-$2,431 |

| Trout |

49 |

$11,753 |

36 |

$13,186 |

-13 |

$1,433 |

| Other Food Fish |

29 |

$11,323 |

32 |

$11,296 |

3 |

-$27 |

| Baitfish |

6 |

$159 |

6 |

$24 |

0 |

-$135 |

| Crustaceans |

8 |

$112 |

8 |

$37 |

0 |

-$75 |

| Mollusks |

38 |

$1,568 |

45 |

$2,278 |

7 |

$710 |

| Ornamental Fish |

25 |

$112 |

9 |

$76 |

-16 |

-$36 |

| Sport/Gamefish |

18 |

$1,004 |

15 |

$3,199 |

-3 |

$2,195 |

| Other Aquaculture |

7 |

$454 |

2 |

(D) |

-5 |

– |

| Total |

211 |

$30,947 |

169 |

$32,127 |

-42 |

$1,180 |

*= x 1,000

South Carolina

South Carolina’s aquaculture industry is characterized by its strong emphasis on marine and coastal species, as well as a growing interest in freshwater production. The state’s favorable climate, extensive coastline, and estuarine environments provide ideal conditions for shellfish and finfish farming. Aquaculture contributes to seafood supply, recreational fisheries, and environmental restoration efforts.

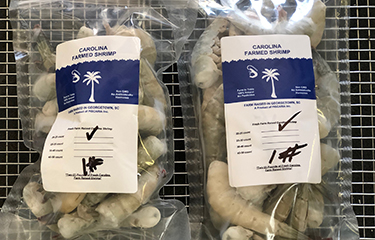

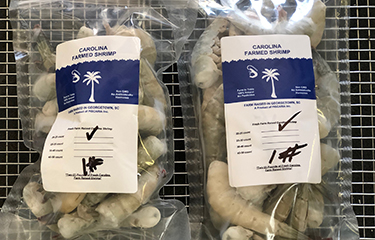

Shellfish and shrimp aquaculture are the flagship species for South Carolina. White Shrimp (Litopenaeus setiferus) aquaculture has been an emerging species and is typically farmed in low salinity, inland ponds. These shrimp grow fast and can reach harvest size in 4-6 months in ideal conditions. On the shellfish side, Eastern Oysters and clams (Mercenaria mercenaria) are the top farmed species in the state. Oyster farming is central to both commercial and restoration activities in South Carolina, while the clam industry supports both local and non-local seafood markets.

Farmed South Carolina Shrimp – Seafood Source

As with most states in the South, South Carolina has a finfish aquaculture sector, specializing in Channel Catfish (Ictalurus punctatus) and Hybrid Striped Bass (Morone chrysops x Morone saxatilis). Both species are usually grown in inland ponds and are used for the commercial food industry and the sportfish industry (pond stocking).

South Carolina’s aquaculture efforts are supported by several key institutions. Clemson University conducts research on fish health, production technologies, and environmental interactions through its Aquaculture and Fisheries Program, while the South Carolina Department of Natural Resources supports shellfish restoration, stock enhancement, and aquaculture development via its Marine Resources Division. The University of South Carolina contributes research focused on water quality and marine organism biology, and the South Carolina Sea Grant Consortium strengthens the industry through research, outreach, and workforce development.

Sea Grant Agent Joshua Kim on a Floating Upweller System (FLUPSY) – SC Sea Grant

| South Carolina Aquaculture |

| Category |

2017 Farms |

2017 Value* |

2023 Farms |

2023 Value* |

+/- Farms |

+/- Value |

| Catfish |

10 |

(D) |

8 |

$292 |

-2 |

– |

| Trout |

1 |

(D) |

5 |

(D) |

4 |

– |

| Other Food Fish |

9 |

(D) |

6 |

$3 |

-3 |

– |

| Baitfish |

1 |

(D) |

5 |

$1 |

4 |

– |

| Crustaceans |

16 |

$616 |

9 |

$101 |

-7 |

-$515 |

| Mollusks |

15 |

$2,525 |

16 |

$29,613 |

1 |

$27,088 |

| Ornamental Fish |

4 |

(D) |

6 |

$161 |

2 |

– |

| Sport/Gamefish |

16 |

$1,296 |

21 |

$3,137 |

5 |

$1,841 |

| Other Aquaculture |

2 |

(D) |

0 |

$0 |

-2 |

– |

| Total |

74 |

$4,437 |

76 |

$33,308 |

2 |

$28,871 |

* = x1,000

Conclusion

Aquaculture in North Carolina and South Carolina exhibits distinct strengths shaped by regional resources, species diversity, and institutional support. North Carolina’s industry leans toward freshwater and hybrid species, while South Carolina excels in marine and shellfish aquaculture. Both states benefit from active research institutions that drive innovation, sustainability, and economic growth in the sector. Continued collaboration and investment in research will be key to advancing aquaculture across the Carolinas.

Next Up – Tennessee and Texas!

References:

North Carolina Aquaculture Census

South Carolina Aquaculture Census

by Thomas Derbes II | Oct 29, 2025

Aquaculture in the Southern United States: Louisiana & Mississippi

Aquaculture has become a cornerstone of food production and rural economic growth across the Gulf Coast. In Louisiana and Mississippi, the industry reflects both states’ deep-rooted connections to water, fisheries, and agriculture. With abundant water resources, a favorable subtropical climate, and established research networks, the region is well-suited for diverse and productive aquaculture operations.

Louisiana and Mississippi rank among the top aquaculture producers in the United States, collectively contributing hundreds of millions of dollars annually to the Gulf Coast economy. Mississippi remains the nation’s top catfish producer, responsible for nearly half of all U.S. farm-raised catfish, while Louisiana leads the country in crawfish production, supplying over 90% of the nation’s farm-raised crawfish.

Beyond these signature species, both states support an array of operations that include oysters, tilapia, hybrid striped bass, shrimp, turtles, and ornamental fish, reflecting a balance of inland and coastal aquaculture.

Louisiana

When you typically think of aquaculture in Louisiana, one species tends to always pop up: the beloved crawfish (crawdad, crayfish, mudbugs, yabbies). Louisiana’s crawfish industry is both an economic powerhouse and a cultural symbol. More than 1,600 crawfish farmers and fishermen produce an estimated 150–200 million pounds annually, contributing over $300 million to the state’s economy. While a significant amount of crawfish are harvested from the wild in marshes and swamps, farm-raised crawfish are typically cultivated in flooded rice fields or specially designed ponds, using a sustainable rotation system that improves soil health and supports biodiversity. In late spring, crawfish ponds are drained to promote mating and burrowing, and a forage crop such as rice is planted in the dry pond. The rice grows through the summer and is harvested in early fall. Before the ponds are refilled, the soil is disked and smoothed to create a suitable seedbed. When the ponds are re-flooded (typically in October) the change in water conditions triggers the hatching of young crawfish, beginning the next production cycle.

Besides crawfish, Louisiana is a top producer of alligator aquaculture, supplying much of the United States with alligator meat and hides. Oyster aquaculture is also taking root in Louisiana. With the constant pressure on wild oysters, oyster aquaculture (both off-bottom and on-bottom) has helped alleviate any extra stress and has added to the filtering potential of the Mississippi Delta and the bayous around Louisiana. Louisiana also maintains a smaller but significant catfish, shrimp, and turtle sector that serves local and regional markets.

In Louisiana, the combined aquaculture sector contributes hundreds of millions in annual sales and supports thousands of jobs in coastal and inland parishes. With its wide range of environments (salt, fresh, marsh, bayou), it is no wonder that Louisiana is a top aquaculture state.

LSU Crawfish Experts – LSU AG Center

Universities like Louisiana State University conduct research to improve aquaculture practices, focusing on disease management, nutrition, genetics, and environmental sustainability. These efforts help producers address challenges and adopt innovative technologies, ensuring the long-term viability of the industry.

| Louisiana Aquaculture |

| Category |

2017 Farms |

2017 Value* |

2023 Farms |

2023 Value* |

+/- Farms |

+/- Value |

| Catfish |

9 |

$490 |

15 |

$3,832 |

6 |

$3,342 |

| Trout |

0 |

$0 |

0 |

$0 |

0 |

$0 |

| Other Food Fish |

5 |

$305 |

0 |

$0 |

-5 |

-$305 |

| Baitfish |

2 |

(D) |

16 |

$360 |

14 |

– |

| Crustaceans |

611 |

$58,823 |

918 |

$131,491 |

307 |

$72,668 |

| Mollusks |

34 |

$9,468 |

50 |

$19,032 |

16 |

$9,564 |

| Ornamental Fish |

6 |

$89 |

17 |

$183 |

11 |

$94 |

| Sport/Gamefish |

6 |

$2,788 |

18 |

$2,073 |

12 |

-$715 |

| Other Aquaculture |

41 |

$61,500 |

55 |

$54,409 |

14 |

-$7,091 |

| Total |

714 |

$133,463 |

1089 |

$211,380 |

375 |

$77,917 |

* – Did not have info due to low number of farms

Mississippi

In Mississippi, aquaculture generates over $230 million annually in farm gate value and supports extensive secondary industries, including feed mills, hatcheries, and equipment manufacturers.

Catfish farming dominates Mississippi’s aquaculture landscape, particularly across the Mississippi Delta, where thousands of acres of ponds support the state’s largest aquaculture output. The catfish industry is one of Mississippi’s most important aquaculture sectors, contributing significantly to the state’s economy, employment, and food production. Mississippi leads the nation in farm-raised catfish production, accounting for more than half of the total U.S. output. The industry developed in the Mississippi Delta in the 1960s, where abundant water resources, fertile soils, and a warm climate created ideal conditions for catfish farming. Today, catfish farms cover tens of thousands of acres, producing hundreds of millions of pounds annually.

Mississippi Catfish Farms on Google Maps

Catfish farming supports thousands of jobs across rural communities, from pond management and feed manufacturing to processing and distribution. Processing plants, many located near growing regions, provide stable employment and generate millions in economic activity. Catfish is also a major component of Mississippi’s agricultural exports and a key source of affordable, high-quality protein for consumers nationwide.

In addition to its economic benefits, the industry has driven research and innovation in aquaculture technology, including water quality management, disease control, and feed efficiency. Despite challenges such as rising production costs and foreign competition, the catfish industry remains a vital part of Mississippi’s agricultural identity and a cornerstone of U.S. aquaculture production. Ongoing research from Mississippi State

University and the Tilapia and striped bass are also grown commercially in Mississippi, but in a smaller, more regional scale. As with most coastal Gulf states, oyster farming has begun to sprout along the limited coastline of Mississippi.

University of Southern Mississippi supports innovation in feed efficiency, disease control, genetics, and environmental management. USM also has stock enhancement programs for local fin fish species and oyster facilities.

Aquaculture remains a vital part of Louisiana and Mississippi’s agricultural landscape. With strong traditions, innovative practices, and continued research, these states are well-positioned to maintain and grow their aquaculture industries, contributing to food security, economic development, and cultural heritage.

| Mississippi Aquaculture |

| Category |

2017 Farms |

2017 Value* |

2023 Farms |

2023 Value* |

+/- Farms |

+/- Value |

| Catfish |

205 |

$219,720 |

142 |

$243,936 |

-63 |

$24,216 |

| Trout |

5 |

$3 |

2 |

(D) |

-3 |

– |

| Other Food Fish |

0 |

$0 |

1 |

(D) |

1 |

– |

| Baitfish |

6 |

$241 |

4 |

$4,192 |

-2 |

$3,951 |

| Crustaceans |

6 |

(D) |

0 |

$0 |

-6 |

– |

| Mollusks |

0 |

$0 |

4 |

$132 |

4 |

$132 |

| Ornamental Fish |

3 |

(D) |

0 |

$0 |

-3 |

– |

| Sport/Gamefish |

25 |

(D) |

16 |

(D) |

-9 |

– |

| Other Aquaculture |

3 |

$350 |

3 |

$228 |

0 |

– |

| Total |

253 |

$220,314 |

172 |

$248,488 |

-81 |

$28,174 |

* – Did not have info due to low number of farms

Up Next – North And South Carolina!

References

Aquaculture Census

Aquaculture Census Fact Sheet

by Thomas Derbes II | Sep 8, 2025

Florida and Georgia are our next two states that are ready for their aquaculture profile. Florida is one of the leaders not only in the South but the whole United States in terms of aquaculture production. Florida is well known for its aquarium trade and food fish aquaculture, and its close location and ease of access to water (salt or fresh) make Florida a prime candidate for aquaculture ventures. Oyster and clam aquaculture have been a staple of the Florida aquaculture industry in the Big Bend area, and there is even an inland salmon farm on the edge of the Everglades!

Catfish and trout farms reign supreme in Georgia, and that comes as no surprise. Georgia is almost completely landlocked and is the base of the Appalachian Mountains, with a warmer, almost tropical climate in the southern portion of the state and a more temperate climate in the northern portion. The North Georgia mountains are known for excellent trout fishing, and state hatcheries have popped up all along the rivers to help increase the stocks of trout for fishermen to enjoy. These hatcheries are leading the way for trout aquaculture research and stock enhancement studies. Georgia is also well known for its sport/gamefish aquaculture industry. Let’s take a look at aquaculture in Florida and Georgia!

Florida

While not the leader in Southern aquaculture, Florida’s diverse landscape and access to salt and freshwater opens the door for a variety of different aquaculture practices throughout the state. Ornamental fish and mollusks (clams and oysters) are the top two producing aquacultured species in Florida, and for Florida’s spotlight we will focus on the ornamental fish and clam industries.

Florida’s ornamental (tropical) fish aquaculture is a dominant economic force, accounting for the largest share of the state’s aquaculture output. In 2023, it generated over $60 million in sales, making Florida the nation’s top pet-fish producer, responsible for about 95 percent of all ornamental fish sold in the U.S., with 90 percent being freshwater species. There are roughly 200 producers cultivating over 800 varieties of freshwater tropical fish, using methods such as earthen ponds, above-ground tanks, and recirculating systems, particularly in Hillsborough, Polk, and Miami-Dade counties. Marine ornamentals are produced at far fewer facilities, about 15 in Florida as of 2023, though they carry higher per-unit value and often rely on advanced recirculating aquaculture systems. These marine ornamental facilities have been instrumental in helping slow down the wild harvest of marine reef fish that has wiped out reefs in Indonesia and other parts of the Pacific.

Blue Tang Juveniles bred at UF Tropical Fish Lab – UF/IFAS

Florida’s clam aquaculture is another key sector. Most production occurs near Cedar Key, which accounts for about 90 percent of the state’s farm-raised clams, generating approximately $32 million in sales in 2023 from 111 growers. Nationwide, Florida ranks second in both the number of clam growers and total sales. The farming process involves hatchery-reared seed, nursery tanks, and deployment of mesh bags on the seafloor for growth before harvest. The industry contributes significantly to regional economies but remains highly vulnerable to hurricanes and storms, which have repeatedly caused disruptive losses and threaten farm infrastructure and livelihoods.

The University of Florida has been a major asset to the shellfish aquaculture industry in Florida, with labs focused on topics ranging from sudden unexplained mortality syndrome (SUMS) to broodstock and larval conditioning. The University of Florida, through UF/IFAS, Tropical Aquaculture Laboratory, and Florida Sea Grant, provides research, education, risk assessments, and extension services for shellfish, ornamental fish, food-fish, and emerging sectors like seaweed farming, helping ensure sustainable, economically viable growth and environmental stewardship in Florida’s diverse aquaculture industry.

Clam Farming – UF IFAS

Meanwhile, the University of Miami Rosenstiel School helps advance marine aquaculture with its Experimental Hatchery, developing hatchery technologies for species like red snapper, cobia, and mahi-mahi, and conducting nutrition and integrated, sustainable multi-trophic systems research to boost commercial viability and coastal resilience. Florida universities remain a leader in aquaculture innovation and research.

| Florida Aquaculture |

| Category |

2017 Farms |

2017 Value* |

2023 Farms |

2023 Value* |

+/- Farms |

+/- Value |

| Catfish |

35 |

$459 |

19 |

$687 |

-16 |

$228 |

| Trout |

2 |

(D) |

1 |

(D) |

-1 |

(D) |

| Other Food Fish |

101 |

$4,254 |

78 |

$24,930 |

-23 |

$20,676 |

| Baitfish |

7 |

$336 |

6 |

$249 |

-1 |

-$87 |

| Crustaceans |

34 |

$4,732 |

41 |

$33,831 |

7 |

$29,099 |

| Mollusks |

162 |

$17,291 |

247 |

$53,348 |

85 |

$36,057 |

| Ornamental Fish |

158 |

$34,506 |

188 |

$62,369 |

30 |

$27,863 |

| Sport/Gamefish |

24 |

$1,784 |

18 |

$1,824 |

-6 |

$40 |

| Other Aquaculture |

113 |

$8,816 |

168 |

$13,860 |

55 |

$5,044 |

| Total |

636 |

$72,178 |

766 |

$191,098 |

130 |

$118,920 |

*x$1,000

Georgia

Florida’s Northern neighbor, Georgia, also has an identity crisis when it comes to climate. The Southern portion of Georgia is known for its vast pine wood forests and almost tropical environment whereas the area North of Atlanta tends to experience a more temperate climate (meaning they really get to experience the seasons, not just Summer Jr, Summer, and “Winter”). Catfish farming takes the number one spot for production, followed closely by sport/gamefish and trout production. Since we have previously discussed catfish farming, let’s take a closer look at the sport/gamefish industry and restoration/stock enhancement trout aquaculture industry in Georgia.

Georgia’s aquaculture sector is modest in scale but diverse and growing, especially in warmwater sportfish like catfish, bass, panfish, and trophy species. The state’s hatcheries, managed by the Georgia Department of Natural Resources (DNR), annually produce around 40 million warmwater fry, fingerlings, and adult fish, including channel catfish, bluegill, redear sunfish, largemouth bass, and striped bass hybrids, primarily for stocking public ponds, small lakes, and reservoir systems to boost recreational fishing opportunities.

Georgia Giant Hybrid Bluegill – Ken’s Hatchery & Fish Farm, Alapaha, Georgia

Georgia’s Wildlife Resources Division within Georgia DNR, in partnership with the U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, stocks around one million rainbow and brown trout annually, dispersed across roughly 160 streams from late March through mid-September. Starting each spring, and occurring almost weekly, they will release about 50,000 trout into North Georgia rivers and creeks, using four hatcheries and nine transport trucks. This program bolsters angler opportunities throughout the state’s nearly 4,000 miles of trout streams.

Trout Being Loaded For Stocking Georgia Rivers – Georgia DNR

Across the private sector, operations routinely culture multiple finfish species: notably catfish (mostly channel and blue), tilapia, and “panfish” like bluegill, redear sunfish, and crappie, as well as bass species, including largemouth, smallmouth, striped and hybrid striped bass. The “Georgia Giant” is a proprietary hybrid sunfish developed by a South Georgia fishery specialist, specifically a cross between female green sunfish and male coppernose bluegill. These Georgia Giants are known for their rapid growth and can reach massive sizes, and they have been a favorite for pond fishermen all around the United States.

The University of Georgia (UGA) plays a central role in supporting this industry through research, extension, and technology transfer. UGA promotes aquaponics and recirculating systems, helping farmers pivot from traditional crops to diversified aquaculture, including sportfish, catfish, tilapia, freshwater prawns, ornamental fish, and even alligators. The state’s favorable climate, abundant natural resources, and strong agricultural infrastructure underpin its potential for further expansion.

| Georgia Aquaculture |

| Category |

2017 Farms |

2017 Value* |

2023 Farms |

2023 Value* |

+/- Farms |

+/- Value |

| Catfish |

47 |

$1,975 |

26 |

$1,692 |

-21 |

-$283 |

| Trout |

16 |

$1,608 |

10 |

$1,145 |

-6 |

-$463 |

| Other Food Fish |

6 |

(D) |

4 |

(D) |

-2 |

(D) |

| Baitfish |

3 |

$24 |

3 |

(D) |

0 |

(D) |

| Crustaceans |

5 |

$54 |

2 |

(D) |

-3 |

(D) |

| Mollusks |

4 |

(D) |

1 |

(D) |

-3 |

(D) |

| Ornamental Fish |

2 |

(D) |

2 |

(D) |

0 |

(D) |

| Sport/Gamefish |

14 |

$3,776 |

11 |

$1,245 |

-3 |

-$2,531 |

| Other Aquaculture |

11 |

(D) |

20 |

(D) |

9 |

(D) |

| Total |

108 |

$7,437 |

79 |

$4,082 |

-29 |

-$3,355 |

*x$1,000

Up Next – Louisiana and Mississippi!

References:

https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2022/Full_Report/Census_by_State/Georgia/index.php

https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2022/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_State_Level/Florida/flv1.pdf

https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2022/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_State_Level/Georgia/gav1.pdf

https://shellfish.ifas.ufl.edu/

by Thomas Derbes II | Aug 25, 2025

The two A states in the South, Alabama and Arkansas, kick off our state aquaculture spotlight portion of our series on Aquaculture in the Southern United States. Alabama and Arkansas together contribute about 9% of all Southern aquaculture, with 102 and 55 farms, respectively. Catfish farming reigns supreme in Alabama, accounting for approximately 50% of all farms in Alabama. Baitfish farming is very popular in Arkansas, and the Arkansas baitfish industry provides over 60% of the baitfish in the United States. Let us take a quick dive into both of these A states!

Alabama Aquaculture

Just like the Song of US States we learned in grade school, we start off our state spotlights with Alabama. Alabama, especially West Alabama, is known for its catfish farms. In 1960, a small channel catfish hatchery opened up in Greensboro, Alabama, and helped jump-start the commercial catfish farming industry.

Environmental and economic factors have favored Alabama’s success, including a warm climate, suitable topography, abundant rain, low energy costs, and proximity to Auburn University’s fisheries expertise. The channel catfish is hardy and adaptable, making it ideal for farming. The STRAL Company, founded by Chester Stephens, Richard True, and Bryant Allen, was pivotal in developing catfish farming. They used methods from U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service researchers and opened the first successful hatchery.

Catfish Harvest – Alabama Extension

The industry faced early challenges, including market oversupply, high feed costs, and disease outbreaks. Technological advancements, such as the paddle-wheel aerator and improved feed, helped address these issues. The establishment of the Alabama Fish Farming Center in 1985 provided essential research and support. The industry also formed marketing associations and legislative measures to combat predators and imported competition.

Down on the coastline, oyster farming is the major contributor to marine aquaculture. In Bayou Le Batre, Point Aux Pins started oyster farming in 2009. Recognized as one of the first pioneer oyster farms in Alabama, Steve and Dema Crockett opened their farm to interested oyster farmers (in fact, it was the first oyster farm I visited). The Crockett’s farm and business, eventually joined by the McClure family, were dedicated to producing off-bottom oysters for upscale restaurants and raw bars around the United States. To this day, they are credited with helping grow and spread oyster aquaculture across the Gulf.

Working an Oyster Farm – Chris Verlinde

Auburn University and their extension program has played a vital role in supporting aquaculture development in Alabama. Currently, Auburn has a lab on Dauphin Island dedicated to oyster aquaculture, an inland shrimp farm in Gulf Shores dedicated to shrimp & pompano aquaculture, and the E.W. Shell Fisheries Center, located just north of campus, dedicated to freshwater aquaculture, catfish genetics, and pond management.

Auburn Students Weighing Farm-Raised Catfish – Auburn Fisheries

The Claude Peteet Mariculture Center, located in Gulf Shores, plays a vital role in marine aquaculture research and production. It features a hatchery used to raise species such as red drum, pompano, and flounder, and earthen ponds to grow out red drum and pompano. The center also conducts research on broodstock management.

| Alabama Aquaculture |

| Category |

2017 Farms |

2017 Value* |

2023 Farms |

2023 Value* |

+/- Farms |

+/- Value |

| Catfish |

141 |

$ 115,781 |

89 |

$ 100,571 |

-52 |

-$15,210 |

| Trout |

1 |

(D) |

1 |

(D) |

0 |

(D) |

| Other Food Fish |

14 |

$ 138 |

14 |

$ 116 |

0 |

-$22 |

| Baitfish |

2 |

(D) |

1 |

(D) |

-1 |

(D) |

| Crustaceans |

10 |

$ 1,260 |

3 |

$ 1,623 |

-7 |

$363 |

| Mollusks |

8 |

(D) |

10 |

$ 992 |

2 |

(D) |

| Ornamental Fish |

6 |

$ 5 |

2 |

(D) |

-4 |

(D) |

| Sport/Gamefish |

38 |

$ 3,644 |

40 |

$ 4,776 |

2 |

$1,132 |

| Other Aquaculture |

13 |

(D) |

16 |

$ 1,231 |

3 |

(D) |

| Total |

233 |

$ 120,828 |

176 |

$ 109,309 |

-57 |

-$11,519 |

*x $1,000

Arkansas Aquaculture

Arkansas is the birthplace of warm-water aquaculture in the United States, with the first commercial goldfish farms established in the 1940s. Since then, the industry has expanded to produce more than 20 species of fish and crustaceans, serving food markets, recreational fishing, the aquarium trade, water gardening, and aquatic weed or parasite control.

The state ranks second nationally in aquaculture production and leads the country in baitfish, largemouth bass, hybrid striped bass fry, and Chinese carp. It also ranks third in catfish production. Lonoke and Monroe counties are home to the world’s largest baitfish, goldfish, largemouth bass, and hybrid striped bass farms. By the mid-2000s, Arkansas farms were selling more than six billion baitfish annually, shipped nationwide and internationally.

Golden Shiner Minnows – Jeremy Trimpey

Catfish farming began in the 1950s and remains a cornerstone of the industry, with major economic impact in counties such as Chicot. However, baitfish aquaculture is the biggest industry in Arkansas, producing about 61% of the nation’s cultured baitfish value. Each year, six billion minnows (primarily golden shiners, fathead minnows, and goldfish) are raised on Arkansas farms and shipped nationwide. With an annual farm-gate value of roughly $23 million and a six- to seven-fold economic impact, the industry supports local economies in counties such as Lonoke, Prairie, and Monroe.

Before farming, most baitfish were harvested from the wild, often leading to ecological risks like accidental transfer of invasive species. Farm-raised baitfish, however, provide a renewable, healthy, and consistent supply. Arkansas became the hub of the industry due to favorable soils, climate, water, transportation, and pioneering farmers who developed production methods with support from the Stuttgart National Aquaculture Research Center. The baitfish industry generates jobs, supports feed mills, supply companies, and live-hauling businesses, and has adopted best management practices to conserve water, ensure biosecurity, and provide sustainable “Quality Bait from the Natural State.”

In addition to large-scale farms, Arkansas has hundreds of thousands of farm ponds managed for livestock water, wildlife, and recreational fishing. Stocking combinations of bass, bluegill, and catfish are common, with populations managed to sustain healthy fisheries.

Aquaculture is especially important in the Arkansas Delta, a region challenged by poverty and unemployment. Fish farms often serve as major local employers and generate demand for supporting businesses such as equipment suppliers, tradespeople, and transport services. Today, aquaculture ranks among Arkansas’s top ten agricultural industries, blending economic significance with ecological and recreational benefits.

UAPB Students With a Fresh Catfish Harvest – UAPB

The University of Arkansas at Pine Bluff is the only university in Arkansas that has an aquaculture program, and is home to the Aquaculture/Fisheries Center of Excellence, a research and extension center that is dedicated to aquaculture research and dissemination of problem-solving information.

| Arkansas Aquaculture |

| Category |

2017 Farms |

2017 Value* |

2023 Farms |

2023 Value* |

+/- Farms |

+/- Value |

| Catfish |

41 |

$ 25,484 |

34 |

$ 30,188 |

-7 |

$ 4,704 |

| Trout |

5 |

$ 2,717 |

5 |

$ 2,965 |

0 |

$ 248 |

| Other Food Fish |

6 |

$ 10 |

1 |

(D) |

-5 |

(D) |

| Baitfish |

47 |

$ 26,530 |

37 |

$ 29,172 |

-10 |

$ 2,642 |

| Crustaceans |

2 |

(D) |

12 |

$ 301 |

10 |

(D) |

| Mollusks |

1 |

(D) |

1 |

(D) |

0 |

(D) |

| Ornamental Fish |

4 |

(D) |

3 |

(D) |

-1 |

(D) |

| Sport/Gamefish |

24 |

$ 15,947 |

27 |

$ 20,177 |

3 |

$ 4,230 |

| Other Aquaculture |

4 |

$ 122 |

7 |

$ 137 |

3 |

$ 15 |

| Total |

134 |

$ 70,810 |

127 |

$ 82,940 |

-7 |

$ 12,130 |

*x $1,000

Up Next – Florida and Georgia!

References

https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2022/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_1_State_Level/Arkansas/arv1.pdf

https://www.nass.usda.gov/Publications/AgCensus/2022/Full_Report/Volume_1,_Chapter_2_County_Level/Alabama/st01_2_022_022.pdf

https://encyclopediaofalabama.org/article/catfish-industry/

https://www.aces.edu/blog/topics/coastal-programs/oysters-in-alabama/

https://alaquaculture.com/state/

https://encyclopediaofarkansas.net/entries/baitfish-industry-3641/

https://uapb.edu/academics/safhs/department-of-aquaculture-fisheries/aqfi-center-of-excellence/

https://agriculture.arkansas.gov/plant-industries/regulatory-section/aquaculture/

by Thomas Derbes II | Aug 17, 2025

While aquaculture is gradually gaining traction in the United States, it’s important to note that this approach to farming has a long and established history in many parts of the world, particularly in Asia. Asia accounts for over 90% of global aquaculture production, with China, India, and Indonesia leading the sector. The most commonly cultivated species in Asia include carp, shrimp/prawns, and tilapia.

Koi Farming in Japan – Dexter’s World

In the United States, the Southern* states are at the forefront of aquaculture, contributing over 50% of the nation’s total domestic aquacultured species and generating $850 million in annual sales. From Louisiana’s renowned crawfish industry to the burgeoning oyster industry in the Atlantic and Gulf states, and the established catfish industry in Mississippi, Alabama, and Arkansas, the Southern states produce some of the most well-known aquacultured seafood. Farmed oysters from the South are commonly found in markets from New York to California, and Louisiana’s crawfish industry supplies much of America’s crawfish boils.

Several universities in the region are at the cutting edge of aquaculture research. Institutions like Auburn University, the University of Florida, Florida State University, Louisiana State University, the University of Southern Mississippi, Mississippi State University, and the University of Georgia are dedicated to developing the best growing techniques and finding solutions to animal health issues. Aquaculture is a rapidly evolving industry, with advancements in husbandry practices and disease resistance occurring daily.

Fresh Farmed Shrimp – Auburn University

In this series, we aim to explore aquaculture in the Southern states comprehensively, breaking down the information by state and, eventually, by species. We hope this series will illuminate the world of aquaculture in America and inspire readers to try some delicious aquacultured seafood.

In Part 2 of our series, we will delve into the aquaculture profiles of Alabama and Arkansas!

* – Southern States for our discussion include Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Georgia, Louisiana, Mississippi, North Carolina, South Carolina, Tennessee, Texas

| States |

# of Farms |

% South |

% USA |

Sales (x $1,000) |

% South |

% USA |

| Alabama |

102 |

6% |

3% |

131,906 |

14% |

7% |

| Arkansas |

55 |

3% |

2% |

84,172 |

9% |

4% |

| Florida |

488 |

27% |

14% |

165,940 |

17% |

9% |

| Georgia |

22 |

1% |

1% |

0* |

0% |

0% |

| Louisiana |

818 |

45% |

24% |

195,244 |

21% |

10% |

| Mississippi |

129 |

7% |

4% |

276,950 |

29% |

15% |

| North Carolina |

95 |

5% |

3% |

33,225 |

3% |

2% |

| South Carolina |

25 |

1% |

1% |

6,961 |

1% |

0% |

| Tennessee |

21 |

1% |

1% |

3,990 |

0% |

0% |

| Texas |

75 |

4% |

2% |

53,914 |

6% |

3% |

| Total South |

1830 |

|

|

952,302 |

|

|

| Total US |

3453 |

|

|

1,908,022 |

|

|

| The Percentage the South Accounts For in US |

53% |

|

|

50% |

|

|

*withheld to avoid disclosing data for individual farms

Resources:

2023 Census of Aquaculture

USDA Economic Resource Division: Aquaculture

Marine Aquaculture in NOAA Fisheries’ Southeast Region

by Thomas Derbes II | May 12, 2025

As we mentioned in the last article, aquaculture is the practice of cultivating aquatic organisms such as fish, shellfish, and aquatic plants. Aquaculture has deep roots in the United States, evolving from small-scale pond operations into a vital industry supporting food production, conservation, and economic growth.

The history of aquaculture in the U.S. dates back to the 19th century. In 1871, the U.S. Congress established the U.S. Commission of Fish and Fisheries (later part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) to investigate declining fish stocks and promote fish culture as a means of population enhancement. Early efforts focused on freshwater species such as brook trout and Atlantic salmon. Hatcheries were built to breed and release young fish into rivers and lakes, primarily for stock enhancement rather than commercial production.

Catfish Harvest – Alabama Extension

Throughout the early 20th century, aquaculture in the U.S. remained largely limited to public hatcheries. However, interest grew in farming species for food as global demand for seafood rose and wild fish stocks declined. By the 1960s and 1970s, technological advancements and growing scientific understanding helped shift aquaculture toward more commercial operations. Tilapia, catfish, and trout became prominent freshwater species cultivated for food. One of the earliest large-scale successes in U.S. aquaculture was the channel catfish industry in the southern states, particularly Mississippi. With ideal conditions and support from land-grant universities (extension), catfish farming expanded rapidly in the 1970s and 1980s, becoming a major contributor to U.S. aquaculture production. Simultaneously, research into saltwater aquaculture gained traction, with species such as oysters, clams, and mussels cultivated along the Atlantic, Gulf, and Pacific coasts.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the U.S. aquaculture industry continued to diversify. Marine finfish like striped bass, cobia, and salmon began to be farmed, though marine aquaculture in the U.S. has grown more slowly than in other countries due to regulatory, environmental, and spatial challenges. Despite these hurdles, shellfish aquaculture (especially oysters) has thrived in many coastal states, supported by improved hatchery technology and restoration efforts.

Workers Harvesting Oysters From Farm – Thomas Derbes II

Here in the Florida Panhandle, we have many examples of aquaculture, ranging from baitfish and shrimp to oysters and clams. Oyster farming might be the most recognizable operation, but there are other inland aquaculture operations that often go unnoticed. For example, the Blackwater Hatchery situated in Blackwater State Forest spawns and releases striped bass for stock enhancement purposes, and there is an inland shrimp farm in Gulf Shores, Alabama, where Auburn University performs valuable research on proper shrimp husbandry techniques.

Fresh Farmed Shrimp – Auburn University

Modern U.S. aquaculture continues to evolve with a focus on sustainability, innovation, and resilience. Advances in recirculating aquaculture systems (RAS), offshore farming, and integrated multi-trophic aquaculture (IMTA) aim to reduce environmental impacts while increasing efficiency. The federal government and several states have also launched initiatives to support responsible aquaculture growth to help meet the increasing demand for domestic seafood.

Today, aquaculture in the United States plays a multifaceted role. It contributes to sustainable seafood supply, supports habitat restoration, and even aids in scientific research and education. According to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), U.S. aquaculture production is valued at over $1.5 billion annually, with shellfish accounting for a significant portion of that value.

From its humble origins in fish hatcheries to its current role in food security and environmental stewardship, aquaculture has become an essential part of America’s blue economy. As the industry moves forward, balancing productivity with environmental care remains at the heart of its future.