by Carrie Stevenson | May 22, 2020

Sea pork comes in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Recently I was walking the beach, enjoying a sunset and looking around at the shells and other oddities in the wrack line where waves deposit their floating treasures. Something bright green and oblong caught my eye. It was emerald in color, smooth yet fuzzy at the same time, and firm to the touch. At first, I thought it was a sea bean–a collective term for the many species of seeds and fruits that float to our shores from tropical locations in the Caribbean or Central/South America. The bright green definitely seemed like something botanical in nature. However, the vast majority of sea beans have a woody, protective shell similar to our more familiar pecans or acorns.

I remembered a family member asking about finding a mystery chunk of pink mass she found on the beach a few years ago. It resembled a pork chop more than anything else.

A different variety of sea pork that really lives up to its name. Photo credit: Stephanie Stevenson, Duval County Master Gardener

Looking closer and consulting a couple of resources, I realized we had both (most likely!) happened upon one of the oddest and often-questioned finds on our beaches: sea pork. Ranging in color from beige and pale pink to red or green, sea pork is a tunicate (or sea squirt), a member of the Phylum Chordata, home to all the vertebrate and semi-vertebrate animals. While they look and feel more like a cross between invertebrate slugs or sponges, the tunicates are more advanced organisms, possessing a primitive backbone in their larval “tadpole” form. Despite their blob-like appearance, they are more closely related to vertebrate animals than they are to corals or sponges.

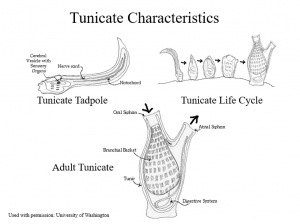

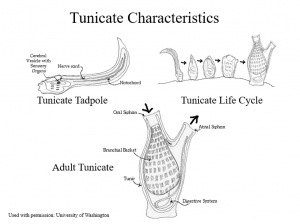

The unusual life cycle of the tunicate. Photo credit: University of Washington, used with permission with Florida Master Naturalist program

During their short (just hours-long) larval stage, the tunicate larvae uses its nerve cord (supported by a notochord similar to a vertebrate spine) to communicate with a cerebral vesicle, which works like a brain. Similar to fish, this primitive brain uses an otolith to orient itself in the water, and an eyespot to detect light. These brain-like tools are utilized to locate an appropriate location to settle permanently. Using a sticky substance, the tunicate will attach its head directly to a hard surface (rocks, boats, docks, etc.) and go through a metamorphosis of sorts. The tunicate reabsorbs its tail and starts forming the shape and structure it needs for adulthood.

As an adult, the organism has a barrel shape covered by a tough tunic-like skin (hence “tunicate”). Adult bodies have two siphons, one to bring water in, another to shoot it out (giving them their other nickname, the sea squirt). The water passes through an atrium with organs that allow it to filter feed, trapping plankton and oxygen. The tunicates will spend most of their lives attached to a surface, pumping water in and out as filter feeders. They may be solitary or live in colonies, and vary widely in color and shape, lending variety to those chunks of sea pork found washing up.

I am still awaiting positive identification from an expert on my green find to confirm that it is, indeed, a tunicate and not an unfamiliar plant. Consulting with Extension colleagues, for now we are pretty confidently going with green sea pork. If you have seen one of these before or something resembling sea pork, let us know! It is fascinating to see the variety and unusual shapes and colors.

.

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 13, 2020

An eastern cottonmouth basking near a creek in a swampy area of Florida.

Photo: Tommy Carter

When you think of reptiles you typically think of tropical rainforest or the desert. However, there is at least one member of the three orders of reptiles that do live in the sea. Saltwater crocodiles are found in the Indo-Pacific region as are about 50 species of sea snakes. There is one marine lizard, the marine iguana of the Galapagos Islands, and then the marine (or sea) turtles. These are found worldwide and are the only true marine reptiles found in the Gulf of Mexico.

Sea turtles are very charismatic animals and beloved by many. Five of the seven species are found in the Gulf. These include the Loggerhead, which is the most common, the Green, the Hawksbill, the Leatherback, and the rarest of all – the Kemp’s Ridley.

Many in our area are very familiar with the nesting behavior of these long-ranged animals. They do have strong site fidelity and navigate across the Gulf, or from more afar, to their nesting beaches – many here in the Pensacola Beach area. The males and females court and mate just offshore in early spring. The females then approach the beach after dark to lay about 100 eggs in a deep hole. She then returns the to the Gulf never to see her offspring. Many females will lay more than one clutch in a season.

The largest of the sea turtles, the leatherback.

Photo: Dr. Andrew Colman

The eggs incubate for 60-70 days and their temperature determines whether they will be male or female, warmer eggs become females. The hatchlings hatch beneath the sand and begin to dig out. If they detect problems, such as warm sand (we believe meaning daylight hours) or vibrations (we believe meaning predators) they will remain suspended until those potential threats are no more. The “run” (all hatchlings at once) usually occurs under the cover of darkness to avoid predators. The hatchlings scramble towards the Gulf finding their way by light reflecting off the water. Ghost crabs, fox, raccoon, and other predators take almost 90% of them, and the 10% who do reach the Gulf still have predatory birds and fish to deal with. Those who make it past this gauntlet head for the Sargassum weed offshore to begin their lives.

These are large animals, some reaching 1000 pounds, but most are in the 300-400 pound range, and long lived, some reaching 100 years. It takes many years to become sexually mature and typically long-lived / low reproductive animals are targets for population issues when disasters or threats arise. Many creatures eat the small hatchings, but there are few predators on the large reproducing adults. However, in recent years humans have played a role in the decline of the adult population and all five species are now listed as either threatened or endangered and are protected in the U.S. There are a couple of local ordinances developed to adhere to federal law requiring protection. One is the turtle friendly lighting ordinance, which is enforced during nesting season (May 1 – Oct 31), and the Leave No Trace ordinance requiring all chairs, tents, etc. to be removed from the beach during the evening hours. There are other things that locals can do to help protect these animals such as: fill in holes dug on the beach during the day, discard trash and plastic in proper receptacles, avoid snagging with fishing line and (if so) properly remove, and watch when boating offshore to avoid collisions.

If we include the barrier islands there are more coastal reptiles beyond the sea turtles. There are freshwater ponds which can harbor a variety of freshwater turtles. I have personally seen cooters, sliders, and even a snapping turtle on Pensacola Beach. Many coastal islands harbor the terrestrial gopher tortoise and wooded areas could harbor the box turtles. In the salt marsh you may find the only brackish water turtle in the U.S., the diamondback terrapin. These turtles do nest on our beaches and are unique to see. Freshwater turtle reproductive cycles are very similar to sea turtles, albeit most nest during daylight hours.

An American Alligator basking on shore.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The American alligator can also be found in freshwater ponds, and even swimming in saltwater. They can reach lengths of 12 feet, though there are records of 15 footers. These animals actually do not like encounters with humans and will do their best to avoid us. Problems begin when they are fed and loose that fear. I have witnessed locals in Louisiana feeding alligators, but it is a felony in Florida. Males will “bello” in the spring to attract females and ward off competing males. Females will lay eggs in a nest made of vegetation near the shoreline and guard these, and the hatchlings, during and after birth. They can be dangerous at this time and people should avoid getting near.

We have several native species of lizards that call the islands home. The six-lined race runners and the green anole to name two. However, non-native and invasive lizards are on the increase. It is believed there are actually more non-native and invasive lizards in Florida than native ones. The Argentina Tegu and the Cuban Anole are both problems and the Brown Anole is now established in Gulf Breeze, East Hill, and Perdido Key – probably other locations as well. Growing up I routinely find the horned lizard in our area. I was not aware then they were non-native, but by the 1970s you could only find them on our barrier islands, and today sightings are rare.

An eastern cottonmouth crossing a beach.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Then there are the snakes.

Like all reptiles, snakes like dry xeric environments like barrier islands. We have 46 species in the state of Florida, and many can be found near the coast. Though we have no sea snakes in the Gulf, all of our coastal snakes are excellent swimmers and have been seen swimming to the barrier islands. Of most concern to residents are the venomous ones. There are six venomous snakes in our area and four of them can be found on barrier islands. These include the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake, the Pygmy Rattlesnake, the Eastern Coral Snake, and the Eastern Cottonmouth. There has been a recent surge in cottonmouth encounters on islands and this could be due to more people with more development causing more encounters, or there may be an increase in their populations. Cottonmouths are more common in wet areas and usually want to be near freshwater. Current surveys are trying to determine how frequently encounters do occur.

Not everyone agrees, but I think reptiles are fascinating animals and a unique part of the Gulf biosphere. We hope others will appreciate them more and learn to live with and enjoy them.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 8, 2019

Over the last two years I have been surveying snakes in a local community on Perdido Key. The residents were concerned about the number of cottonmouths they were seeing and wanted some advice on how to handle the situation. Many are surprised by the number of cottonmouths living on barrier islands, we think of them as “swamp” residents. But they are here, along with several other species, some of which are venomous. Let’s look at some that have been reported over the years.

The dune fields of panhandle barrier islands are awesome – so reaching over 50 ft. in height. This one is near the Big Sabine hike (notice white PVC markers).

In the classic text Handbook of Reptiles and Amphibians of Florida; Part One – Snakes (published in 1981), Ray and Patricia Ashton mention nine species found on coastal dunes or marshes. They did not consider any of them common and listed the cottonmouth as rare – they seem to be more common today. In a more recent publication (Snakes of the Southeast, 2005) Whit Gibbons and Michael Dorcas echo what the Ashton’s published but did add a few more species, many of which I have found as well. Their list brings the total to 15 species. I have frequently seen four other species in Gulf Breeze and Big Lagoon State Park that neither publication included, but I will since they are close to the islands – this brings the total 19 species that residents could encounter.

Leading us off is the one most are concerned about – the Eastern Cottonmouth (Agkistrodon piscivorous). Though listed as “rare” by the Ashton’s, encounters on both Pensacola Beach and Perdido Key are becoming common. There is more than one subspecies of this snake – the eastern cottonmouth is the local one – and that the water moccasin and cottonmouth are one in the same snake. This snake can reach 74 inches in length (6ft). They are often confused with their cousin the copperhead (Agkistrodon contorix). Both begin life in a “copper” color phase and with a luminescent green-tipped tail. But at they grow, the cottonmouth becomes darker in color (sometimes becoming completely black) while the copperhead remains “copper”. The cottonmouth also has a “mask” across its eyes that the copperhead lacks. Believe it or not, the cottonmouth is not inclined to bite. When disturbed they will vibrate their tail, open their mouth showing the “cottonmouth” and displaying their fangs, and swiveling their head warning you to back off. Attacking, or chasing, rarely happens. I find them basking in the open in the mornings and seeking cover the rest of the day. Turning over boards (using a rake – do not use your hand) I find them coiled trying to hide. MOST of the ones I find are juveniles. These are opportunistic feeders – eating almost any animal but preferring fish. They hunt at night. Breeding takes place in spring and fall. The females give live birth in summer. As mentioned earlier, they seem to be becoming more common on our islands.

Eastern Cottonmouth with distinct “mask” and flattened body trying to intimidate.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

This year, while surveying for cottonmouths, I encountered numerous Eastern Coachwhips (Masticophis flagellum). These long slender snakes can reach lengths of 102” (8ft.), move very fast across the ground – often with their heads raised like a cobra – and, even though nonvenomous, will bite aggressively. They get their name from their coloration. They have a dark brown head and neck and a tan colored body – resemble an old coachwhip. They like dune environments and are excellent climbers. They consume lizards, small birds and mammals, and even other small snakes. They are most active during the daylight, but I usually find them beneath boards and other debris hiding. They have always been on the islands but encountered more often this past year. They lay eggs and do so in summer.

Their close cousin, the Southern Black Racer (Coluber constricta) is very similar but a beautiful dark black color. They can reach lengths of 70” (6ft.) and are also very fast. Like their cousin, they are nonvenomous but bite aggressively – often vibrating their tail like cottonmouths warning you to stay back. They are beneficial controlling amphibian, reptile, and mammalian animals. They are also summer egg layers.

The southern black racer differs from otehr black snakes in its brillant white chin and thin sleek body.

Photo: Jacqui Berger.

There are a few freshwater snakes that, like the cottonmouth do not like saltwater, but could be found on the islands. These are in the genus Nerodia and are nonvenomous. There are two species (the Midland and Banded water snakes) that could be found here. They resemble cottonmouths in size and color and are often confused with them. They differ in that they have vertical dark stripes running across their jaws and have a round pupil. Though nonvenomous, they will bite aggressively. One member of the Nerodia group is the Gulf Coast Salt Marsh Snake (Nerodia clarkii clarkii). This snake does like saltwater and is found in the brackish salt marshes on the island. It is dark in color with four longitudinal stripes, two are yellow and two are a dull brown color. It only reaches a length of 36” (3ft.), is nocturnal, and feeds on estuarine fish and invertebrates.

This banded water snake is often confused with the cottonmouth. This animal has the vertical stripes extending from the lower jaw, which is lacking in the cottonmouth.

Photo: University of Georgia

Other species that the guides mention, or I have seen, are the small Crowned Snake, Southern Hognose, Pine Snake, Pine Woods Snake, and the Rough Green Snake. I will mention here species I have seen in either Gulf Breeze or Big Lagoon State Park that COULD be found on the island: Eastern Coral Snake, Eastern Garter Snake, Pigmy Rattlesnake, Eastern Hognose, and the Corn Snake (also called the Red Rat Snake). Only two of these (Eastern Coral and Pigmy) are venomous.

Last, but not least, is the Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake (Crotolus adamateus). This is the largest venomous snake in the United States, reaching 96” (8ft.). It is a diurnal hunter consuming primarily small mammals, though large ones can take rabbits. They prefer the dry areas of the island where cover is good. Palmettos, Pine trees, and along the edge of wetlands are their favorite haunts. Despite their preference for dry sandy environments, they – like all snakes – are good swimmers and large rattlesnakes have been seen swimming across Santa Rosa Sound and Big Lagoon. They tend to rattle before you get too close and you should yield to this animal. The have an impressive strike range, 33% of their body length, you should give these guys a wide berth. I have come across several that never rattled, I just happen to see them. Again, give them plenty of room when walking by.

Eastern diamondback rattlesnake swimming in intracoastal waterway near Ft. McRee in Pensacola.

Photo: Sue Saffron

It is understandable that people are nervous about snakes being in popular vacation spots, but honestly… they really do not like to be around people. We are trouble for them and they know it. Most encounters are in the more natural areas of the islands. Staying on marked trails and open areas, where you can see them – and be sure to look down while walking, you should see them and avoid trouble. For more questions on local snakes, contact me at the county extension office.

References

Ashton, R.E., P.S. Ashton. 1981. Handbook of Reptiles and Amphibians of Florida; Part One – Snakes. Windward Publishing, Miami FL. Pp.176.

Gibbons, W., M. Dorcas. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. University of Georgia Press, Athens GA. Pp. 253.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 18, 2019

Yep,

We are still trying to remove this invasive plant from our area. For those who are not familiar with it, beach vitex (Vitex rotundifolia) is a category I invasive plant in Florida. It is current listed as “invasive, not recommended”. This means you can still purchase it but recommend you do not.

Vitex growing at Gulf Islands National Seashore that has been removed. Photo credit: Rick O’Connor

Why is that?

Well, being an invasive species, it reproduces at a high rate, has few consumers, and causes an environmental issue wherever it grows. It has the potential to cause economic issues as well. Beach vitex is from Asia and was brought to the United States as an ornamental plant. In upland landscapes, it does not seem to be a problem. However, when first used in coastal dunes it began to show its ugly head. Vitex begins as a low growing vine and becomes a shrub over time. It produced a beautiful lavender blossom in spring but then produces millions of seeds in late summer and fall. The seeds are spread by birds and are viable in seawater for several months. Dispersed in this way, the plant spreads across coastal beaches of our barrier islands.

Once established it forms a taproot with above ground rhizomes extending as far as 20 feet. It is allelopathic, meaning it produces chemical compounds that kill nearby plants and spreads to cover this new territory. This includes the common sea oat. Sea oats have a fibrous root system which are good at trapping sand and forming dunes. These dunes can protect properties during storm surge. Beach vitex, having a taproot system, are not as effective. Though we are not aware of any beach vitex growing on the fore dune in the panhandle, if it does it could impact sea turtle nesting. We are also not sure whether the local beach mice will eat these seeds. Thus, displacing sea oats could impact beach mice.

Beach Vitex Blossom. Photo credit: Rick O’Connor

We currently know of one site in Ft. Pickens, two properties in Gulf Breeze, two in Navarre, four on Perdido Key and Perdido Bay, 24 within Naval Live Oaks in Gulf Breeze, and 38 on Pensacola Beach; 70 properties total in the Pensacola Bay area. One of the properties in Gulf Breeze, and nine on Pensacola Beach (14%) have been removed or treated and have not returned. One property in Gulf Breeze, one in Ft. Pickens, two on Perdido Key and Perdido Bay, 20 on Pensacola Beach, and 24 in Naval Live Oaks (68%) have been removed or treated but have returned; re-treatments are required and are being conducted. And one property in Gulf Breeze, two in Navarre, two on Perdido Key or Perdido Bay, and nine on Pensacola Bay (20%) have not been removed or treated at all. In each of these cases, the plants are on private property. We hope that these property owners would consider removing the plant and replacing with native dune plants from this area.

Elsewhere in the panhandle we are aware of only two locations, one in Okaloosa County and one in Franklin. We believe the property in Okaloosa has been treated and are not sure of the status in Franklin. If is very possible that this plant is in the coastal areas of other counties in the panhandle.

Recently, volunteers from the Pensacola Beach Advocates and Americorp removed 315 m2 of beach vitex from public land on Pensacola Beach. That now means all beach vitex on public lands in Escambia County have been removed or treated. Research shows that repeated treatments may be required for up to five years to completely eradicate the plant from that property, but PBA and Americorp plan to assist Sea Grant with removing this plant from the area.

If you believe you have this plant and would like to learn how to manage it. Contact Rick O’Connor at the Escambia County Extension Office. (850) 475-5230 ext.111.

Vitex beginning to take over bike path on Pensacola Beach. Photo credit: Rick O’Connor

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 28, 2018

In the past week, three eastern diamondback rattlesnakes were encountered near the Ft. Pickens area on Pensacola Beach. The first was at a condominium unit near the park gate where construction work was occurring, the second was found swimming in the surf of the Gulf of Mexico within the national seashore, and the third was in the national seashore’s campground. This is an animal we rarely encounter on our barrier islands – but that is the keyword… encounter… they are there, but tend to avoid us.

Eastern diamondback rattlesnake crawling near Ft. Pickens Campground.

Photo: Shelley Johnson

Report on rattlesnake in Gulf surf –

https://www.pnj.com/story/news/local/2018/09/26/snake-rescue-pensacola-beach-shocks-visitors/1430731002/

The eastern diamondback rattlesnakes (Crotalus adamanteus) is the largest venomous snake in the United States. An average snake will reach six feet and five pounds, but they can reach eight feet and up to 15 pounds. Because of their large bodies, they tend to move slow and do not often try to escape when approached by humans. Rather, they lie still and quite hoping to be missed. If they do feel you have come to close, they will give their signature rattle as a warning – though this does not always happen. If they are considering the idea of striking – they will raise their head in the classic “S” formation. Know that their strike range is 2/3 their body length – larger than many other native snakes – so a four foot snake could have a three foot strike range. Give these snakes plenty of clearance.

Eastern diamondback rattlesnakes prefer dry sandy habitats, though they are also found in pine flatwoods (such as Naval Live Oaks north of highway 98 in Gulf Breeze). They are quite common in the upland sandhills of longleaf pine forests. They spend the day in tree stump holes and gopher burrows and hunt small mammals and birds in the evenings. They are particular fond of rabbits. The dunes of our barrier islands are very similar to the sandhills of the pine forest further north. They are actually good swimmers and saltwater is not a barrier – distance is. They have been seen numerous times swimming from Gulf to Pensacola Beach or the opposite. Again, they tend to avoid encounters with humans and are not often found on lawns etc.

Diamondbacks give birth to live young around August. The females will find a dark-cool location to den and give birth several young. Anywhere from four to 32 offspring have been reported. The female remains with the young for about 10 days until they have their first molt (skin shedding) and then she leaves them to their fate.

Diamondback rattlesnake near condominium construction site Pensacola Beach.

Photo: Sawyer Asmar

So what’s up with three encounters in a relatively small location within one week?

My first inclination is two possibilities – maybe a combination of the two.

- We have had a lot of rain this year – and then T.S. Gordon came through. Snakes like to be on high dry ground as much as anyone else and they tend to move closer to human habitats because they are built on higher ground.

- Breeding season for eastern diamondbacks is late summer early fall. This time of year, the males are on the move seeking interested females – so they are encountered more.

As far as finding one in the surf of the Gulf of Mexico. I am not sure. I have never seen this and the newspaper account suggested it was not doing well when found. Again, I have seen plenty swimming the Intracoastal but this is a first for the Gulf. I would say it had wondered the wrong way.

They are actually fascinating animals and are not a threat unless you approach too close. Give them room and feel lucky if you get to see one.

References

Eastern Diamondback Rattlesnake. Natural History. Center for Biological Diversity. https://www.biologicaldiversity.org/species/reptiles/eastern_diamondback_rattlesnake/natural_history.html.

Krysko, Kenneth L., and F. Wayne King. 2014. Online Guide to the Snakes of Florida. Florida Museum of Natural History, University of Florida, Gainesville, FL, USA. [Online: September 2014] Available at: http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/herpetology.

https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/herpetology/fl-snakes/list/crotalus-adamanteus.

by Carrie Stevenson | Nov 3, 2017

Red mangrove growing among black needlerush in Perdido Key. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Discovering something new is possibly the most exciting thing a field biologist can do. As students, budding biologists imagine coming across something no one else has ever noticed before, maybe even getting the opportunity to name a new bird, fish, or plant after themselves.

Well, here in Pensacola, we are discovering something that, while already named and common in other places, is extraordinarily rare for us. What we have found are red mangroves. Mangroves are small to medium-sized trees that grow in brackish coastal marshes. There are three common kinds of mangroves, black (Avicennia germinans), white (Laguncularia racemosa), and red (Rhizophora mangle).

Black mangroves are typically the northernmost dwelling species, as they can tolerate occasional freezes. They have maintained a large population in south Louisiana’s Chandeleur Islands for many years. White and red mangroves, however, typically thrive in climates that are warmer year-round—think of a latitude near Cedar Key and south. The unique prop roots of a red mangrove (often called a “walking tree”) jut out of the water, forming a thick mat of difficult-to-walk-through habitat for coastal fish, birds, and mammals. In tropical and semi-tropical locations, they form a highly productive ecosystem for estuarine fish and invertebrates, including sea urchins, oysters, mangrove and mud crabs, snapper, snook, and shrimp.

Interestingly, botanists and ecologists have been observing an expansion in range for all mangroves in the past few years. A study published 3 years ago (Cavanaugh, 2014) documented mangroves moving north along a stretch of coastline near St. Augustine. There, the mangrove population doubled between 1984-2011. The working theory behind this expansion (observed worldwide) is not necessarily warming average temperatures, but fewer hard freezes in the winter. The handful of red mangroves we have identified in the Perdido Key area have been living among the needlerush and cordgrass-dominated salt marsh quite happily for at least a full year.

Key deer thrive in mangrove forests in south Florida. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Two researchers from Dauphin Island Sea Lab are planning to expand a study published in 2014 to determine the extent of mangrove expansion in the northern Gulf Coast. After observing black mangroves growing on barrier islands in Mississippi and Alabama, we are working with them to start a citizen science initiative that may help locate more mangroves in the Florida panhandle.

So what does all of this mean? Are mangroves taking over our salt marshes? Where did they come from? Are they going to outcompete our salt marshes by shading them out, as they have elsewhere? Will this change the food web within the marshes? Will we start getting roseate spoonbills and frigate birds nesting in north Florida? Is this a fluke due to a single warm winter, and they will die off when we get a freeze below 25° F in January? These are the questions we, and our fellow ecologists, will be asking and researching. What we do know is that red mangrove propagules (seed pods) have been floating up to north Florida for many years, but never had the right conditions to take root and thrive. Mangroves are native, beneficial plants that stabilize and protect coastlines from storms and erosion and provide valuable food and habitat for wildlife. Only time will tell if they will become commonplace in our area.

If you are curious about mangroves or interested in volunteering as an observer for the upcoming study, please contact me at ctsteven@ufl.edu. We enjoy hearing from our readers.