by Rick O'Connor | Jun 11, 2020

Well, maybe not…

But there could be reason to keep an eye out. We are not talking about the common ribbed or hooked mussels we found in the Pensacola Bay area. We are talking about an invasive species called the green mussel (Perna viridis).

The green mussel differs from the local species by having a smooth shell and the green margin.

Photo: Maia McGuire Florida Sea Grant

Why be concerned?

By nature, invasive species can be environmentally and/or economically problematic. In this case, it is more economic – which is unusual, most are more environmental concerns. The big problem is as a fouling organism. Like zebra mussels (Dreissena polymorpha), green mussels grow in dense clusters, covering intact screens to power plants, intact pipes to water plants, and can displace native spaces by competing for space. It has been determined they can grow to densities of 9600 mussels / m2 (that’s about 10 ft2) and they can do this on local oyster reefs – displacing native, and economically important, oysters. They grow quickly, being sexually mature in just a few months, and disperse their larva via the currents. To make things more interesting, they may be host to diseases that could impact oyster health.

So, what is the situation?

They are from the Indo-Pacific region, found all across southeast Asia and into the Persian Gulf. In this part of the world they are an aquaculture product. There was interest in starting green mussel aquaculture in China, and in Trinidad-Tobago. After they arrived in Trinidad, they were discovered in Venezuela, Jamaica, and Cuba – it is not believed this was due to re-locating aquaculture, but rather by larva dispersal across the sea… they got away.

This cluster of green mussels occupies space that could be occupied by bivavles like osyters.

It would be an easy jump from Cuba to Florida – and they came. The first record was in 1999 in Tampa Bay. They were found while divers were cleaning an underwater intake screen. Dispersal could have happened via larva transport in the currents, but it could have also occurred via ship ballast discharge at the port – this is how folks think it got there, they really do not know. From there they began to spread across the peninsula part of the state. They have been reported in 19 counties, most on the Gulf coast, and there is a record from Escambia County – however, that one was not confirmed.

How would I know one if I saw it?

They prefer shallow water and are often found in the intertidal zones – attached to pilings, seawalls, rocks. As mentioned, they grow in dense clusters and should be easy to find. They are long and smooth, with a mean length of 3.5 inches. There was one found in Florida measuring 6.8 inches, which they believe is a world record. Mussels differ from oysters in that they attach using “hairy” fibrous byssal threads – in lieu of cementing themselves as oysters do. As mentioned, the shell is smooth and may have growth rings, but it lacks the “ribbed” pattern we see on the local ribbed and hooked mussel. It will have a green coloration along the margin – hence its name, and the interior of the shell will be pearly white.

The shell at the far right is the common ribbed mussel native to our local salt marshes. Just to the left is the invasive green mussel. Can you tell them apart?

Photo: Maia McGuire Florida Sea Grant

They prefer salinities between 20-28‰, which would be the lower portions of the Pensacola Bay system (Santa Rosa Sound, Big Lagoon, maybe portions of Pensacola Bay). They are not a fan of cold water. They do not like to be in water at (or colder) than 60°F. Some biologist believe it is too cold in the panhandle for these bivalves, but we should report any we think may be them – to be sure.

What do we do if found?

1) Get a location and photos. Pull some off and get up close photos of an individual.

2) Report it. You can do this by contact the Escambia County extension office (850-475-5230 ext.111), or email me at roc1@ufl.edu.

3) If there is a method of removing all of them, do so. But this should be done only after the identification is verified. When removing try to collect all the shell material. The fertilized gametes within, if left, can still disperse the animal.

4) They are suggesting boat owners check their vessels when trailering. Avoid transporting them from one body of water to another.

5) I would recommend that marina owners do the same – check boats and pilings.

It appears the mean temperature of the Gulf is increasing. With this change it is possible some of the tropical species common in south Florida could disperse to our region, and that could include the green mussel. The most effective (and cheapest) way to manage an invasive species is catch them early and remove them before they can become established.

For more information on green mussels in Florida read https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/SG/SG09400.pdf.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 29, 2020

Baby terns on Pensacola Beach are camouflaged in plain sight on the sand. This coloration protects them from predators but can also make them vulnerable to people walking through nesting areas. Photo credit: UF IFAS Extension

The controversial incident recently in New York between a birdwatcher and a dog owner got me thinking about outdoor ethics. Most of us are familiar with the “leave no trace” principles of “taking only photographs and leaving only footprints.” This concept is vital to keeping our natural places beautiful, clean, and safe. However, there are several other matters of ethics and courtesy one should consider when spending time outdoors.

- On our Gulf beaches in the summer, sea turtles and shorebirds are nesting. The presence of this type of wildlife is an integral part of why people want to visit our shores—to see animals they can’t see at home, and to know there’s a place in the world where this natural beauty exists. Bird and turtle eggs are fragile, and the newly hatched young are extremely vulnerable. Signage is up all over, so please observe speed limits, avoid marked nesting areas, and don’t feed or chase birds. Flying away from a perceived predator expends unnecessary energy that birds need to care for young, find food, and avoid other threats.

When on a multi-use trail, it is important to use common courtesy to prevent accidents. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

- On a trail, the rules of thumb are these: hikers yield to equestrians, cyclists yield to all other users, and anyone on a trail should announce themselves when passing another person from behind.

- Obey leash laws, and keep your leash short when approaching someone else to prevent unwanted encounters between pets, wildlife, or other people. Keep in mind that some dogs frighten easily and respond aggressively regardless of how well-trained your dog is. In addition, young children or adults with physical limitations can be knocked down by an overly friendly pet.

- Keep plenty of space between your group and others when visiting parks and beaches. This not only abides by current health recommendations, but also allows for privacy, quiet, and avoidance of physically disturbing others with a stray ball or Frisbee.

Summer is beautiful in northwest Florida, and we welcome visitors from all over the world. Common courtesy will help make everyone’s experience enjoyable.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 22, 2020

Sea pork comes in a wide variety of shapes and sizes. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Recently I was walking the beach, enjoying a sunset and looking around at the shells and other oddities in the wrack line where waves deposit their floating treasures. Something bright green and oblong caught my eye. It was emerald in color, smooth yet fuzzy at the same time, and firm to the touch. At first, I thought it was a sea bean–a collective term for the many species of seeds and fruits that float to our shores from tropical locations in the Caribbean or Central/South America. The bright green definitely seemed like something botanical in nature. However, the vast majority of sea beans have a woody, protective shell similar to our more familiar pecans or acorns.

I remembered a family member asking about finding a mystery chunk of pink mass she found on the beach a few years ago. It resembled a pork chop more than anything else.

A different variety of sea pork that really lives up to its name. Photo credit: Stephanie Stevenson, Duval County Master Gardener

Looking closer and consulting a couple of resources, I realized we had both (most likely!) happened upon one of the oddest and often-questioned finds on our beaches: sea pork. Ranging in color from beige and pale pink to red or green, sea pork is a tunicate (or sea squirt), a member of the Phylum Chordata, home to all the vertebrate and semi-vertebrate animals. While they look and feel more like a cross between invertebrate slugs or sponges, the tunicates are more advanced organisms, possessing a primitive backbone in their larval “tadpole” form. Despite their blob-like appearance, they are more closely related to vertebrate animals than they are to corals or sponges.

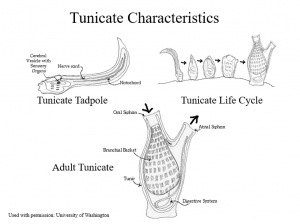

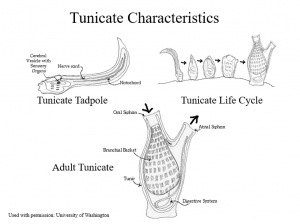

The unusual life cycle of the tunicate. Photo credit: University of Washington, used with permission with Florida Master Naturalist program

During their short (just hours-long) larval stage, the tunicate larvae uses its nerve cord (supported by a notochord similar to a vertebrate spine) to communicate with a cerebral vesicle, which works like a brain. Similar to fish, this primitive brain uses an otolith to orient itself in the water, and an eyespot to detect light. These brain-like tools are utilized to locate an appropriate location to settle permanently. Using a sticky substance, the tunicate will attach its head directly to a hard surface (rocks, boats, docks, etc.) and go through a metamorphosis of sorts. The tunicate reabsorbs its tail and starts forming the shape and structure it needs for adulthood.

As an adult, the organism has a barrel shape covered by a tough tunic-like skin (hence “tunicate”). Adult bodies have two siphons, one to bring water in, another to shoot it out (giving them their other nickname, the sea squirt). The water passes through an atrium with organs that allow it to filter feed, trapping plankton and oxygen. The tunicates will spend most of their lives attached to a surface, pumping water in and out as filter feeders. They may be solitary or live in colonies, and vary widely in color and shape, lending variety to those chunks of sea pork found washing up.

I am still awaiting positive identification from an expert on my green find to confirm that it is, indeed, a tunicate and not an unfamiliar plant. Consulting with Extension colleagues, for now we are pretty confidently going with green sea pork. If you have seen one of these before or something resembling sea pork, let us know! It is fascinating to see the variety and unusual shapes and colors.

.

by Rick O'Connor | May 17, 2020

In my time educating the public about Florida turtles I have found that most Floridians have not heard of diamondback terrapins. They have heard of, and seen turtles, but are not sure what the names of the different species are and are not familiar with the term terrapin at all. Which brings up the question – what is the different between a turtle, a tortoise, and a terrapin?

The light colored skin and dark markings are pretty unique to the terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Honestly, they are cultural terms and not “biological” descriptions. We associate the term “tortoise” with a land turtle – and this is true – yet we call the box turtle a “turtle” – which is fine. In Great Britain they call almost everything a “terrapin”. The term “terrapin” is a Delaware Indian term meaning “edible turtle”. Most turtles are edible, but this term stuck to a group of brackish water turtles in the Chesapeake area near Delaware we now call “terrapins”.

In the Mid-Atlantic states, terrapins are more known than they are here – and they appear to be more abundant. They are the mascot of the University of Maryland, and the official state reptile there. “Turtle Soup”, a popular cultural dish in the Chesapeake, is made with terrapins. It was served as part of the state dinner when Abraham Lincoln was president – considering it a classic “American” dish. They were harvested by walking through the marshes with a burlap sack and a gig. A sack could bring a harvester about $10, but when the popularity of the dish increased, hand harvesting could not keep up with demand and terrapin farms began. I know there were terrapin farms in the Carolinas, but there was one near Mobile, Alabama as well. Apparently, terrapins existed outside of the Chesapeake – and that brings us back to Florida… we have them too!

Ornate Diamondback Terrapins Depend on Coastal Marshes and Sea Grass Habitats

There are seven subspecies of this brackish water turtle. They range from Massachusetts to Texas. It is the only resident brackish water species, spending its whole life in salt marshes (or mangroves in south Florida). Florida has five of the seven subspecies, and three of the seven ONLY live in Florida – yet most of us do not know the animal exist.

Very few researchers worked with terrapins in this state – there was virtually nothing known about them in panhandle. In 2005 I began to survey panhandle marshes to see if terrapins existed here. I grew up in the panhandle, and like so many others, had never seen or heard of one. I asked local fishermen who use to gillnet the marshes back in the 1950s and 1960s (when it was allowed) if they were aware of this this turtle. I asked them “did you ever capture a terrapin?” They did not know what I was talking about. And then I showed them a picture… “OH… yea, we did catch these once in a while – what are they called again? Terrapins?”. This was a game changer for me in terrapin education – show them a terrapin and ask if they have ever seen a turtle that looks like this.

The response was still “what is that? It’s beautiful!”… and they are. Terrapins have light colored skin with dark specks or bars – a really pretty cool looking turtle. Oh, and they are in the panhandle, just not in big numbers – or, at least, we have not found them in big numbers 😊.

These brackish water turtles spend their entire lives in a marsh system feeding on mollusk and crustaceans. Like map turtles (their nearest cousins), the females are larger with wide heads for crushing the shells of their prey. They are considered an important member of the ecosystem in that the reduction of terrapins can cause an increase in the marsh periwinkle (a popular snail food) who would in turn stop feeding on leaf litter and attack the live plants themselves – threatening the existence of the marsh. So, they are important predators on marsh grazers. Not having a lot of trees in a salt marsh, you do not see them basking on logs as you do with other riverine turtles. They do, however, exit the water and bury in the mud/sand for long periods to bask.

A baby terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

After mating, the females usually leave the marsh for the open estuary, swim along the shorelines looking for high/dry ground for nesting. More often than not, these are sandy beaches – but they have been known to dig nest in crushed shell mounds, dredge spoil islands, along highways, backyards, and even runways of airports – wherever “high and dry” can be found in a marsh. In Louisiana a lady found one roaming around inside her outdoor shower – good luck nesting there!

The females lay about 10 eggs in a clutch and will lay more than one clutch each year. Baby terrapins are one of the coolest looking turtles you will see. They emerge from the nest in late summer and fall, hiding in the wrack debris along the shoreline. It is believed they actually have a more terrestrial life early on before entering the water and living out their lives in the marsh.

The popularity of turtle soup has waned since the Civil War, as have the wild harvest and aquaculture projects. However, the turtle is still under tremendous pressure from humans. We began using wired crab traps in the 1950s and terrapins have a habit of swimming into these, where they drown. The problem is not that large in Florida, but in the Chesapeake, they have found as many as 40 terrapins in one crab trap! Most of these are “ghost crab traps” – ones that “got away” from the owner but are still harvesting marine live – including crabs. One paper indicated that in the early part of the 21st century, in one year in the Chesapeake, over 900,000 blue crabs died in ghost crab traps – a commercial value of about $300,000. So, the ghost crab trap is a problem whether it kills terrapins, redfish, flounder, or blue crab. Today, many crab traps have biodegradable panels so that if the trap “gets away” it will eventually breakdown and not capture organisms like terrapins. In the Chesapeake many states require crab traps to have a By-Catch Reduction Device (BRD) to keep terrapins out – but allow crabs in. They are not required in Florida, however FWC will provide them for free if you are interested. I have some in my office in Pensacola and more than willing to give them to you. FWC also hosts crab trap removal programs, and I encourage you to participate in these.

This orange plastic rectangle is a Bycatch Reduction Device (BRD) used to keep terrapins out of crab traps – but not crabs.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

A bigger issue for Florida is the land-based predators. As we moved closer and closer to the salt marshes, we built bridges and roads that allowed land-based predators to reach the nesting beaches they previously did not have access to. Raccoons in particular are a big problem, depredating as many as 90% of the terrapin nests. Poaching for the pet trade is rising and FWC is working on this. Several major arrests have been made in Florida in recent years. It is illegal to sell Florida turtles, so do not buy them if you see them being sold somewhere. Report the activity to FWC.

Due to all of this, terrapins afford some form of protection in each of the coastal states where they exist. Some list them as “endangered” or “threatened”. In Florida, they do not have this label, but they are protected by FWC. No one is allowed to have more than two in their possession, and you are not allowed to have any eggs.

It is an amazing turtle. I currently conduct a citizen science program monitoring them in the western panhandle. I have a lot of eager volunteers wanting to see their first one in the wild. I hope they do soon. I hope they hang around long enough for everyone to see one in the wild.

by Rick O'Connor | May 14, 2020

As we embrace the marine life of the Gulf of Mexico during this year of “Embracing the Gulf”, we are currently hooked on worms. In the last article we talked about the gross and creepy flatworms. Gross because they are flat, pale in color, only have a mouth so they have to go to the bathroom using it – and creepy in that many of them are parasites, living in the bodies over vertebrates (particularly fish) and that is just creepy. You may ask why would we even “embrace” such a thing? Well… because they do exist and most of us know nothing about them.

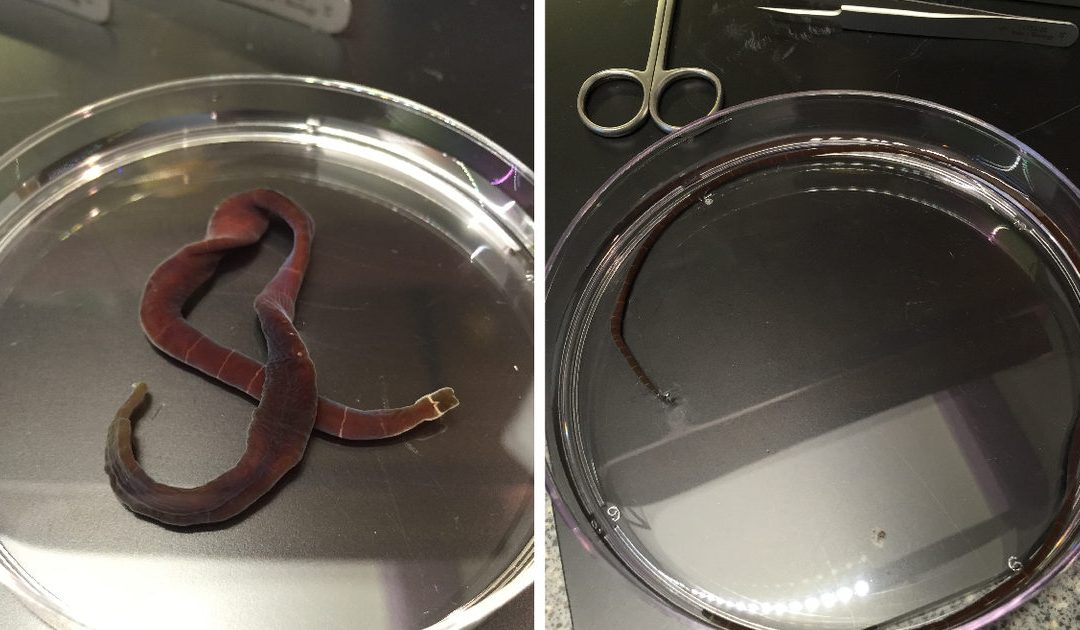

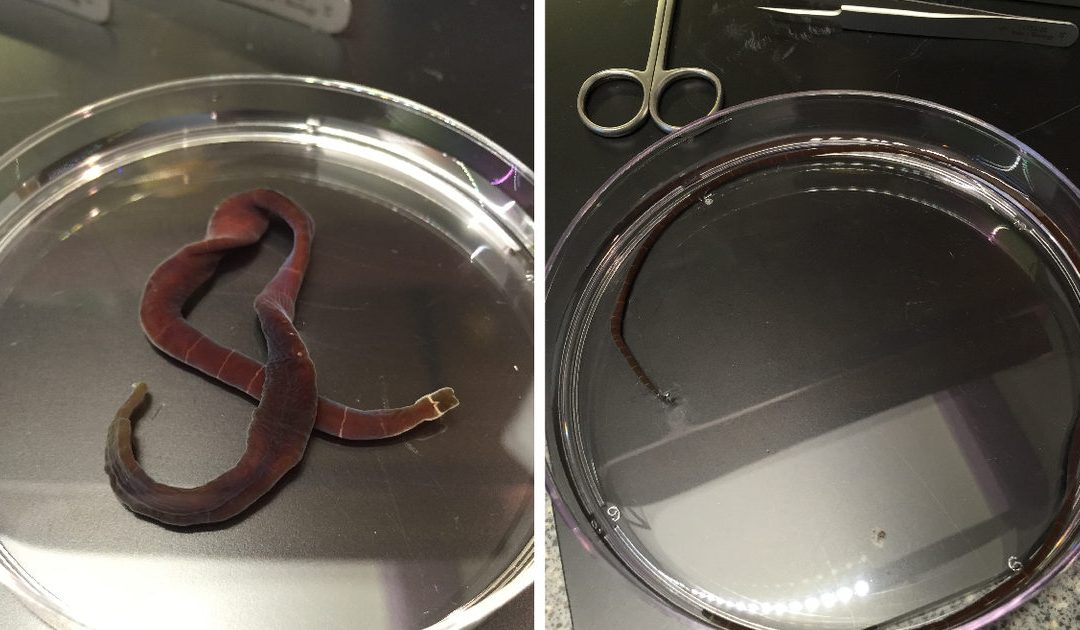

A nemertean worm.

Photo: Okinawa Institute of Science

This week we continue with worms. We continue with a different kind of flatworm. They are not as gross, but maybe a little creepy. They are called nemertean worms and I am pretty sure (a) you have never heard of them, and (b) you have never seen one. So why “embrace” these? Well… again it is education. They do exist, and one day you MAY see one – and know what you are looking at.

Nemerteans are flatworms. They are usually pale in color but a different from the classis fluke or tapeworm in a couple of ways.

1) They do have a way for food to enter and another for waste to leave, what we call a complete digestive tract – and that’s nice.

2) They have this long extension connected to their head called a proboscis. Many of them have a dart at the end they can use to kill their prey – and that’s creepy.

3) And as mentioned, most are carnivores, feeding on small invertebrates – and that’s okay.

We rarely see them because they are nocturnal – hiding under rocks, shells, seaweed during the day and hunting at night. Most are about eight inches long but some in the Pacific reach almost eight feet!

I would put that in the creepy file.

As we said, they are usually pale in color, though some may have yellow, orange, red, or even green hues to them. Their heads are spade shaped and, again, hold a retracted proboscis. This proboscis can be over half the length of the worm. At the end is a stylet (a dart) which they can use to stab their prey (small invertebrates). They can stab repeatedly, like using a knife, – they may stab and grab, like using a claw – or they may be a species that has toxin and kills their prey that way.

Nice.

Some would add this to the creepy file as well. A long pale worm, moving at night, extending a long proboscis when they get near you with a sharp dart at the end they essentially “sting” you like a bee.

Yea, creepy.

But we NEVER hear about such things with humans. They hunt small invertebrates like amphipods, isopods, and things like that. If you picked one up, would it stick the dart in you? My hunch would be yes – I honestly don’t know, I have only seen one to two in the 35+ years I have been teaching marine science and I did not pick them up. I have never met anyone who has and have never read “DON’T PICK THESE UP – VERY DANGERSOUS”. So, my hunch is that it would not be very painful at all.

But don’t take my word for it – again, I have rarely seen one… so, don’t pick them up 😊

There are about 650 species of nemertean worms in the world, 22 live in the Gulf of Mexico, and 16 live in the northern Gulf (near us). They are basically marine, move across the environment on their slime trails, seeking prey primarily by the sense of smell at night. Unlike the flukes and tapeworms, there are male and females in this group. They fertilize their eggs externally to make the next generation of these harpooning hunters of the Gulf.

I don’t know if you will ever come across one of these. You will know it by the flat body, pale color, and spade-shaped head, but I think it would be pretty neat to find one. There are more worms to learn about in the Gulf of Mexico, but we will do that in another edition.

by Carrie Stevenson | May 8, 2020

In ecology, a “keystone” species is as crucial to an ecosystem as the central stone in this arch.

In architecture, a “keystone” is the top, central block in an arch structure, the one that holds the entire building up. Without it, the bricks around it collapse. With it, there is nothing stronger.

So, when you hear an animal referred to as a “keystone” species, it should get your attention—especially when that species is listed as threatened by state and federal wildlife agencies. In northwest Florida, one of the species upon which the entire longleaf ecosystem is built is the humble gopher tortoise (Gopherus polyphemus).

Gopher tortoises are long-lived, protected by their thick shells and deep burrows. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Once hunted for food and currently in competition with humans for buildable land, this long-lived reptile is an architect in its own right. The tortoises are called “gophers” because of their tunnel building and burrow construction expertise. The tortoises spend about 80% of their time near their burrows, of which they have multiple over their lifetimes. Being a cold-blooded reptile, the burrows allow the tortoises a place to live in the temperature-regulated soil.

The average adult gopher tortoise is about 9-11 inches long, although they can be larger. They have thick feet resembling those of an elephant, and scaly front legs used for digging and burrowing. They are tan, brown, or gray, and live in dry, sandy, upland habitats. Their propensity for dry forestland is typically why their populations are in peril, as this is also the best land for building and development.

The average gopher tortoise’s burrow is 6.5 feet deep and 15-40 feet long, and provides habitat for 350 other species! Those commensal species that share its burrow are mostly invertebrates, but at least 50 are larger backboned species like frogs, snakes, rabbits, and burrowing owls. During forest fires, there are stories of multiple species—from deer and snakes and turtles—calling a truce and hiding in the burrows together until the flames blow over.

Gopher tortoises are nesting right now–be sure to observe from a distance!

Right now—from May to July—is nesting season for gopher tortoises. They lay eggs in the soft sand of their burrow apron, which is the triangular spread of loose sand at the opening of the burrow. Eggs incubate all summer and emerge between August and November. The newly hatched tortoises can expect to live 40 to 60 years in the wild. They live on a variety of grasses and low-growing plants native to longleaf pine, oak forests, and coastal dunes, including wiregrass and gopher apple. They are adapted to routine fires, as they are safe in their burrows and the new growth after a burn provides an abundance of their grassy food sources.