by Rick O'Connor | Mar 29, 2019

We have a lot of really cool and interesting creatures that live in our bay, but one many may not know about is a small turtle known as a diamondback terrapin. Terrapins are usually associated with the Chesapeake Bay area, but actually they are found along the entire eastern and Gulf coast of the United States. It is the only resident turtle of brackish-estuarine environments, and they are really cool looking.

The diamond in the marsh. The diamondback terrapin.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

Terrapins are usually between five and 10 inches in length (this is the shell measurement) and have a grayish-white colored skin, as opposed to the dark green-black found on most small riverine turtles in Florida. The scutes (scales) of the shell are slightly raised and ridged to look like diamonds (hence their name). They are not migratory like sea turtles, but rather spend their entire lives in the marshes near where they were born. They meander around the shorelines and creeks of these habitats, sometimes venturing out into the seagrass beds, searching for shellfish – their favorite prey. Females do come up on beaches to lay their eggs but unlike sea turtles, they prefer to do this during daylight hours and usually close to high tide.

Most folks living here along the Gulf coast have not heard of this turtle, let alone seen one. They are very cryptic and difficult to find. Unlike sea turtles, we usually do not give them a second thought. However, they are one of the top predators in the marsh ecosystem and control plant grazing snails and small crabs. During the 19th century they were prized for their meat in the Chesapeake area. As commonly happens, we over harvested the animal and their numbers declined. As numbers declined the price went up and the popularity of the dish went down. There was an attempt to raise the turtles on farms here in the south for markets up north. One such farm was found at the lower end of Mobile Bay.

Early 20th century still found terrapin on some menus, but the popularity began to wane, and the farms slowly closed. Afterwards, the population terrapins began to rebound – that was until the development of the wire meshed crab trap. Developed for the commercial and recreational blue crab fishery, terrapins made a habitat of swimming into these traps, where they would drown. In the Chesapeake Bay area, the problem was so bad that excluder devices were developed and required on all crab traps. They are not required here in Florida, where the issue is not as bad, but we do have these excluders at the extension office if any crabber has been plagued with capturing terrapins. Studies conducted in New Jersey and Florida found these excluder devices were effective at keeping terrapins out of crab traps but did not affect the crab catch itself. Crabs can turn sideways and still enter the traps.

This orange plastic rectangle is a Bycatch Reduction Device (BRD) used to keep terrapins out of crab traps – but not crabs.

Photo: Rick O’Connor

Another 20th century issue has been nesting predation by raccoons. As we began to build roads and bridges to isolated marsh islands in our bays, we unknowingly provided a highway for these predators to reach the islands as well. On some islands, raccoons depredated 90% of the terrapin nests. Today, these turtles are protected in every state they inhabit except Florida. Though there is currently no protection for the terrapin itself in our state, they do fall under the general protection for all riverine turtles; you may only possess two at any time and may not possess their eggs.

Some scientists have discussed identifying terrapins as a sentinel species for the health of estuaries. Not having terrapin in the bay does not necessarily mean the bay is unhealthy, but the decline of this turtle (or the blue crab) could increase the population of smaller plant grazing invertebrates they eat throwing off the balance within the system.

Sea Grant trains local volunteers to survey for these creatures within our bay area. Trainings usually take place in April and surveys are conducted during May and June. This year we will be training volunteers in the Perdido area on April 10 at the Southwest Branch of the Pensacola Library on Gulf Beach Highway. That training will begin at 10:00 AM. For Pensacola Beach the training will be on April 15 at the Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Conservation Center on Navarre Beach. That training will begin at 9:00 AM. A third training will take place on April 22 at the Port St. Joe Sea Turtle Center in Port St. Joe. For more information on diamondback terrapins contact me at the Escambia County Extension Office – (850) 475-5230 ext. 111.

by Scott Jackson | Mar 29, 2019

Boats at a calm rest in Massalina Bayou, Bay County, Florida.

Wow! I was so excited to hear the news. Dad had just called to invite me on a deep sea trip out of Galveston. I had grown up fishing but had never been to sea. My mind raced – surely the fish would be bigger than any bass or catfish we ever caught. I day dreamed for a few moments of being in the newspaper with the headline, “Local Teen Catches World Record Red Snapper”.

It seemed more like a Christmas Morning when dad woke me up for our 100-mile car trip to the coast. We hurried to breakfast just a few hours before sunrise. I had the best fluffy pancakes with a lot of syrup, washed down with coffee with extra cream and sugar. I was wide awake and ready for the fishing adventure of a lifetime!

The crew welcomed us all aboard and helped us settle in. Dad was still tired and went to nap below deck. I was outside taking in all the sights of a busy head boat, including the smell of diesel fuel, bait, and dressed fish. About an hour into my great fishing adventure things started to change. I grew queasy and tired. I went to find my dad and he was already sick. I looked at him and then turned around to go out the ship’s door. My eyes saw the horizon twist sideways and my brain said “WRONG!!!” – this was my first encounter with seasickness.

The crew quickly moved both of us back outside. I was issued a pair of elastic pressure wristbands – the elastic holds a small ball into the underside of your wrist. The attention and sympathy might have made me feel a little better but there was really no recovery until we got back into the bay an excruciating 6 hours later. There were no headlines to write this day, only the chance to watch others catch fish while my stomach and head churned – often in opposite directions.

Fast forward to today, decades later. I often make trips into Gulf to help deploy artificial reefs without any problems with motion sickness. Some of my success in avoiding seasickness are lessons I learned from that dreadful introduction to deep sea fishing long ago.

- Be flexible with your schedule to maximize good weather and sea conditions. If you are susceptible to motion sickness in a car or plane this is an important indicator. Sticking to an exact time and date could set you up for a horrible experience. Charter companies want your repeat business and to enjoy the experience over and over again.

- Get plenty of rest before your fishing adventure. Come visit and if necessary spend the night. Start your day close to where you will be boarding the boat.

- Eat the right foods. You don’t need much food to start the day, keep it light and avoid fatty or sugary diet items. As the day goes by, eat snacks and lunch if you get hungry.

- Stay hydrated and in balance. Take in small sips when you are queasy or have thrown up. You need to drink but consuming several bottles of water in a short time period can create nausea.

- Avoid the smell zone. When possible, position yourself on the vessel to avoid intense odors like boat exhaust or fish waste in order to keep your stomach settled. It is best to stay away from other seasick individuals as their actions can influence your nausea.

- Mind over matter – Have confidence. Knowing you have prepared yourself to be on the water with sleep, diet, and hydration is often enough to avoid seasickness. However, if you routinely face motion or seasickness then a visit with your doctor can provide the best options to make your days at sea a blessing. Their help could be the final ingredient in your personal recipe for great times on the water with friends and family.

For more information, contact Scott Jackson at the UF/IFAS Extension Bay County Office at 850-784-6105.

by Laura Tiu | Mar 6, 2019

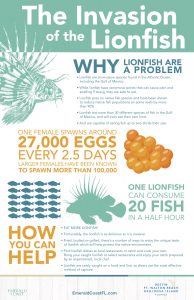

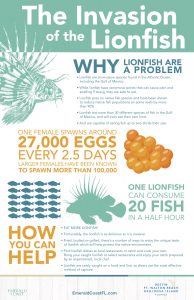

The northwest Florida area has been identified as having the highest concentration of invasive lionfish in the world. Lionfish pose a significant threat to our native wildlife and habitat with spearfishing the primary means of control. Lionfish tournaments are one way to increase harvest of these invaders and help keep populations down.

Located in Destin FL, and hosted by the Gulf Coast Lionfish Tournaments and the Emerald Coast Convention and Visitors Bureau, the Emerald Coast Open (ECO) is projected to be the largest lionfish tournament in history. The ECO, with large cash payouts, more gear and other prizes, and better competition, will attract professional and recreational divers, lionfish hunters and the general public.

You do not need to be on a team, or shoot hundreds of lionfish to win. Get rewarded for doing your part! The task is simple, remove lionfish and win cash and prizes! The pretournament runs from February 1 through May 15 with final weigh-in dockside at AJ’s Seafood and Oyster Bar on Destin Harbor May 16-19. Entry Fee is $75 per participant through April 1, 2019. After April 1, 2019, the entry fee is $100 per participant. You can learn more at the website http://emeraldcoastopen.com/, or follow the Tournament on Facebook.

The Emerald Coast Open will be held in conjunction with FWC’s Lionfish Removal & Awareness Day Festival (LRAD), May 18-19 at AJ’s and HarborWalk Village in Destin. The Festival will be held 10 a.m. to 5 p.m each day. Bring your friends and family for an amazing festival and learn about lionfish, taste lionfish, check out lionfish products! There will be many family-friendly activities including art, diving and marine conservation booths. Learn how to safely fillet a lionfish and try a lionfish dish at a local restaurant. Have fun listening to live music and watching the Tournament weigh-in and awards. Learn why lionfish are such a big problem and what you can do to help! Follow the Festival on Facebook!

“An Equal Opportunity Institution”

by Laura Tiu | Mar 6, 2019

Artificial Reef Pyramid (Photo: L. Tiu)

The Northwest Florida Regional Artificial Reef Workshop was held February 20 at the Emerald Coast Convention Center in Fort Walton Beach Florida. It followed the Northwest Florida Regional Lionfish Workshop held the day before as many in the audience have interest in both lionfish and artificial reefs. Okaloosa County Commissioner, Captain Kelly Windes, gave the welcome, sharing his experiences as a lifelong local and a 3rd generation charter boat captain operating for over 30 years.

Keith Mille, Director of the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission Artificial Reef Program gave the state updates. In the state of Florida, a total of 3,534 patch reefs have been deployed. In 2018, 187 new patch reefs were added to the mix. These reefs are made from concrete, formed modules, vessels, barges, metal and rock. The Atlantic side received 33 new patch reefs, while the Gulf side deployed 154. Many of the Gulf reefs are funded using Natural Resource Damage Assessment (NRDA) monies intended to compensate anglers and divers for loss of use during the 2010 Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill. According to a recent economic evaluation of artificial reefs by the University of West Florida’s Dr. Bill Huth, fishing and diving on Escambia County’s artificial reefs support 2,348 jobs and account for more than $150 million in economic activity each year.

County updates for Escambia, Santa Rosa, Okaloosa, Walton, Bay, City of Mexico Beach, Franklin, and Wakulla followed with Victor Blanco, Florida Sea Grant Agent from Taylor County, sharing his process for developing and training a volunteer research dive team to monitor the reefs.

University of Florida researchers provided a reef fish communities update highlighting the response of gray trigger fish and red snapper populations near the reefs, as well as the impact of lionfish on these communities. They also provided answers to the question of how artificial reefs function ecologically versus as fishing habitat. This research hopes to enhance future assessments concerning siting and function of artificial reefs. An anthropologist from Florida State University described his role in conducting cultural resource surveys for artificial reefs. The day ended with a report on the assessment of artificial reefs impacted by Hurricane Michael and a demonstration of updated software used to create side scan mosaics for monitoring.

Presentations were recorded and are available on the Florida Artificial Reefs Facebook page. A statewide Artificial Reef Summit is being organized for February 2020 and will be a great opportunity to learn more about Florida reefs.

“An Equal Opportunity Institution”

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 31, 2019

“The Gulf of Mexico provides food, shelter, protection, security, energy, habitat, recreation, transportation, and navigation – playing an important role in our communities, states, region, and nation. To highlight the value and the vitality of the Gulf of Mexico region, the Gulf of Mexico Alliance conceived an awareness campaign “Embrace the Gulf” for the entire year 2020. The awareness campaign will culminate in a multi-stakeholder, cross-sector celebration of the importance of the Gulf of Mexico throughout the year 2020.” (https://embracethegulf.org/about/)

Join the Gulf of Mexico Alliance as we celebrate the importance of the Gulf of Mexico during the year 2020. The Gulf of Mexico Alliance is a regional partnership that works to “sustain the resources of the Gulf of Mexico. Led by the five Gulf States, the broad partner network includes federal agencies, academic organizations, businesses, and other non-profits in the region. Our goal is to significantly increase regional collaboration to enhance the environmental and economic health of the Gulf of Mexico.” (https://gulfofmexicoalliance.org/about-us/organization/).

The Gulf of Mexico Alliance (GOMA) was established in 2004 by the Governors of the Gulf states, as a response to the President’s Ocean Action Plan. It began as a network of state partnerships that worked together on various strategies related to the GOMA priority issues identified by the Governors of each state. It had strong support from the U.S. Council on Environmental Quality. Today GOMA is led by the EPA and NOAA, with 13 federal agencies support the effort. Learn more.

A great blue heron enjoying the Gulf of Mexico.

Photo: Chris Verlinde

To celebrate the year 2020 and the importance of Gulf of Mexico, the Embrace the Gulf campaign was created by the Education and Engagement Priority team. The GOMA leadership supports the idea and the campaign has gathered support from the other priority areas.

There are many ways for you and or your organization to get involved. You can plan an event to celebrate the Gulf of Mexico. You can utilize GOMA marketing resources to promote the campaign. Click here to learn about the available marketing resources.

The E& E team is collecting 365 facts to promote the Gulf of Mexico. You can support this effort by submitting Gulf of Mexico facts using the online form that is located here. Facts will be used on social media, the GOMA website and more. Please support this effort by submitting today!!

Check out this You Tube video GOMA produced to promote the beauty and importance of the Gulf of Mexico. Join us as we celebrate 2020 to Embrace the Gulf!!

by Laura Tiu | Jan 31, 2019

They say that dreams don’t work unless you take action. In the case of some Walton County Florida dreamers, their actions have transpired into the first Underwater Museum of Art (UMA) installation in the United States. In 2017, the Cultural Arts Alliance of Walton County (CAA) and South Walton Artificial Reef Association (SWARA) partnered to solicit sculpture designs for permanent exhibit in a one-acre patch of sand approximately .7-miles from the shore of Grayton Beach State Park at a depth of 50-60 feet. The Museum gained immediate notoriety and has recently named by TIME Magazine as one of 100 “World’s Greatest Places.” It has also been featured in online and print publications including National Geographic, Lonely Planet, Travel & Leisure, Newsweek, The New York Times, and more.

Seven designs were selected for the initial installation in summer of 2018 including: “Propeller in Motion” by Marek Anthony, “Self Portrait” by Justin Gaffrey, “The Grayt Pineapple” by Rachel Herring, “JYC’s Dream” by Kevin Reilly in collaboration with students from South Walton Montessori School, “SWARA Skull” by Vince Tatum, “Concrete Rope Reef Spheres” by Evelyn Tickle, and “Anamorphous Octopus” by Allison Wickey. Proposals for a second installation in the summer of 2019 are currently being evaluated.

The sculptures themselves are important not only for their artistic value, but also serve as a boon to eco-tourism in the area. While too deep for snorkeling, except perhaps on the clearest of days, the UMA is easily accessible by SCUBA divers. The sculptures are set in concrete and contain no plastics or toxic materials. They are specifically designed to become living reefs, attracting encrusting sea life like corals, sponges and oysters as well large numbers and varieties of fish, turtles and dolphins. This fulfills SWARA’s mission of “creating marine habitat and expanding fishery populations while providing enhanced creative, cultural, economic and educational opportunities for the benefit, education and enjoyment of residents, students and visitors in South Walton.”

The UMA is a diver’s dream and is in close proximity to other Walton County artificial reefs. There are currently four near-shore snorkel reefs available for snorkeling and nine reefs within one mile of the shore in approximately 50-60 feet of water for additional SCUBA opportunities. All reefs are public and free of charge for all visitors with coordinates available on the SWARA website (https://swarareefs.org/). Several SCUBA businesses in the area offer excursions to UMA and the other reefs of Walton County.

For more information, please visit the UMA website at https://umafl.org/ or connect via social media at https://www.facebook.com/umaflorida/.

Schools of fish swim by the turtle reef off of Grayton Beach, Florida. Photo credit: University of Florida / Bernard Brzezinski