by Rick O'Connor | Aug 10, 2024

I was recently conducting a survey for diamondback terrapins from my paddleboard in a small estuarine lagoon within the Pensacola Bay System. Even if we do not find our target species during these surveys – I, and our volunteers, see all sorts of other cool wildlife. On this trip I was treated to nesting osprey, a kingfisher, large blue crabs, and even a swimming eel. But one neat encounter was the numerous stingrays.

The Atlantic Stingray is one of the common members of the ray group who does possess a venomous spine.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

They were lying in the sand and grassbeds, lots of them, and they all seemed to be of one species – the Atlantic stingray. My brain immediately went to “breeding season”, but when I checked the literature, I found that it was not breeding season, but pupping season – the babies were being born.

Atlantic Stingray (Dasyatis sabina) are true stingrays in the family Dasyatidae. This means they do possess the replaceable serrated venomous barb that makes these animals so famous. They are one of the smaller members of this family. Females can reach a disk width of two feet while the smaller males will only reach about one foot. Atlantic stingrays are a warm water species, migrating if they need to find suitable temperatures. They have been found in water as deep as 80 feet but are more common in the warmer shallower waters near shore. They are very common in our estuaries and being euryhaline (they tolerate a large range of salinity), are found in freshwater systems. There is a population that lives in the St. Johns River. Atlantic stingrays feed on a variety of benthic invertebrates and have special cells in the nose to detect the weak electric fields their prey give off while buried in the sediment. They also like to bury in the sand to ambush prey as they move by.

Breeding occurs in the fall. The smaller males possess two modified fins called claspers connected to their anal fins that are used to transfer sperm to the female. The males have modified teeth they can use to bite the fins of the females. They do this to hold on and make sperm transfer more successful.

The females do not begin to ovulate until spring. So, though they receive the sperm in the fall, fertilization does not occur until the spring. Instead of laying eggs, as some rays and skates do, baby Atlantic stingrays develop within the mother. This is not the same as mammals, who produce a placental to feed the developing young, but more like an internal egg with no hard shell. The embryo is attached to, and feeds from, a yolk sac. Gestation takes about 60 days at which time the yolk sac is depleted, and the young must emerge. Birth usually occurs in late July and early August, and each female will produce 1-4 small pups whose disk are about 10cm (4in.) wide. It was this birthing/pupping period I witnessed.

I returned the following day to search for terrapins and the number of stingrays was significantly fewer. It may be that the birthing process is fast, and the adults leave the coves afterwards. It may have been because that day was the day Hurricane Debby was making landfall east of us and the water levels were abnormally high – something the rays may have noticed and decided to leave – I am not sure.

I was really hoping to see the young rays swimming around – I did not – but plan to search again soon. Stingrays make many people nervous. I witnessed several adult rays whose tails had been cut off – which is very unfortunate – but they are actually cool creatures and fun to watch while paddleboarding. Maybe I will see a baby soon.

References

Dasyatis sabina. 2023. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/dasyatis-sabina/.

Johnson, M.R., Snelson Jr., F.F. 1996. Reproductive Life History of the Atlantic Stingray, Dasyatis sabina (Pisces, Dasyatidae), in Freshwater St. Johns River, Florida. Bulletin of Marine Science, 59(1): 74-88.

by Erik Lovestrand | Jun 28, 2024

One of several “flatfish” inhabiting our Panhandle coastal waters, the ocellated flounder (Ancylopsetta ommata) is one of the more striking species, in my opinion. From the four distinctive eye spots (ocelli) to its incredible variability in background patterns, I must just say that it is a beautiful creature. Flounders are unique among fish, in that early during larval development one eye will migrate over to join the other and the fish will orient to lay on its side when at rest. Only the top side will have coloration and the bottom side will be white. While the eyes end up on the same side, the pectoral and pelvic fins remain in their traditional positions, although the bottom-side pectoral fin is reduced in size.

Not the Biggest but Definitely one of the Coolest Flounder Species Around

Ocellated flounders are always left-eyed, meaning if you stood them up vertically with their pelvic fins down, the left side of the body has the eyes. When laying on the ocean floor, their independently moving eyes can keep a lookout in all directions. However, flounders tend to remain immobile when approached, depending on an awesome ability to camouflage themselves from predators. They can flip sand or gravel onto their top side which hides their outline and their ability to match the color and texture of the surrounding substrate is phenomenal.

This species is a fairly small fish, reaching lengths of about ten inches. However, they are by no means the smallest flatfish around. We also have hogchokers (a member of the sole family, 6-8 in.) and blackcheek tonguefish (to 9 in.). These are dwarfed by the larger Gulf flounder and Southern flounder which are highly prized table fare by fishers along our coasts and can reach sizes that earn them the nickname of “doormat” flounders. Regardless of the species of flounder you observe, it is unquestionably one of the super cool animals we have the privilege of living with here along the North Florida Gulf Coast.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 21, 2024

Today’s society is more educated about sharks and shark behavior than our forefathers. In the 18th, 19th, and much of the 20th century we thought of sharks as mindless eating machines – consuming anything available. Whalers would witness sharks consuming carcasses, as did many other fishermen. Sailors noted sharks following the smaller boats across the ocean, always present when bad situations occurred.

During World War II the U.S. Navy was moving across the Pacific and a deeper understanding of sharks was needed to keep servicemen safe. The sinking of the USS Indianapolis pushed the Navy into a larger research program to determine how to repel sharks and better understand what made them tick. After the war funding for such research continued. One of the leading researchers was Dr. Eugene Clark, who eventually founded the Mote Marine Laboratory in Sarasota with the intention of developing a better understanding of shark behavior. Dr. Clark frequently appeared on the Undersea World of Jacques Cousteau educating the public about how sharks function and respond to their environment. All with the idea of how to better reduce negative shark encounters.

Pregnant Bull Shark (Carcharhinus leucas) cruses sandy seafloor. Credit Florida Sea Grant Stock Photo

In the 1970s Peter Benchley wrote Jaws but included a marine biologist as one of the key characters who would provide science insight into how sharks work. The film was a cultural phenomenon. I remember standing in a line that wrapped the cinema twice to get in. This was followed by more funding for shark research and a better understanding of how they work. This was then followed by a popular summer series known as “Shark Week”, which remains popular to this day. Many of the old tales of shark behavior were disproved or explained. The idea of a mindless eating machine was replaced with a fish that actually thinks and responds to certain cues. People began to realize that shark attacks are quite rare and could be explained if we understood what happened leading up to the attack.

We now understand that sharks are fish, in a class where the members have cartilaginous skeletons (they lack true bone). They are one of the most perceptive creatures in the ocean, using their senses to detect potential prey and that there are signals that can “turn them on”. On the side of their bodies there is a line of small gelatinous cells that can detect slight vibrations in the ocean – from up to a mile away. The ocean is a noisy place, and it appears that sharks respond to different frequencies. I like to use the analogy of yourself being in a large student cafeteria. Everyone is talking and it is very noisy. Then someone calls your name. Somehow, amongst all the background clatter, you hear this and respond to it. Studies suggest that sharks do the same. With all of the noise moving though the ocean, sharks hear things that catch their attention and then move towards the source.

Blacktip sharks are one of the smaller sharks in our area reaching a length of 59 inches. They are known to leap from the water. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

As they get closer their sense of smell kicks in. Everyone has heard that sharks can detect small amounts of blood in large amounts of seawater – remember “Bruce” from Finding Nemo? It is true, but they do have to be down current to pick up the scent and they will now focus their search to find the source. Some studies suggest other “odors”, such as the urine of seals, might produce the same reaction that blood does. All may lead to shark to think a possible meal is nearby.

Eyesight is not great with any creature in the sea. Light does not travel well in water – but sharks do have eyes and they do see well (one of the old tales science disproved – that sharks are basically “blind”). However, because of the low light, they do have to be close to the target to get a visual. Some studies suggest that sharks are detecting shadows or shapes they may confuse as a potential prey, bite it, and then release when they discover it was not what they thought it was. This idea is supported by the fact that many who are bitten experience what is called “bite and release” – and they turn and swim away. It is also known that sharks have structures in the back of their retinas that act as mirrors, collecting what light is available, reflecting it within the eye, and illuminating their world. They believe they see pretty well at night – better than us for sure. The image they see may appear to be a prey item and may be what is producing the vibrations and odors that they detected.

The Scalloped Hammerhead is one of five species of hammerheads in the Gulf. It is commonly found in the bays. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

And they have one more “sixth sense” – the ability to detect weak electric fields. The shark’s mouth is not in position to attack prey as they move forward. It is on the bottom of their head and, one of the old tales, was that sharks must swim over their prey to bite it. Video taken during the filming for Jaws showed that the shape of the shark’s head changes at the last moment of an attack. The entire head becomes distorted to get the mouth in the correct position for the bite. The “eyes roll back” – as the old fishermen used to say – and the jaws move up and forward. At this point the shark can no longer use its eyes to zero in on the target. However, they have small cells around their snout called the Ampullae of Lorenzini that can detect the small electric fields produced by muscle movement – even the prey’s heartbeat – and know where they are. But – they must be very close to the prey to detect this.

Understanding all of this gives scientists, and the public, a better idea of how sharks work. What “turns them on” and how/when they will select prey. One thing that has come from all of this is that we do not seem to be high on their target list.

The Great White shark.

Photo: UF IFAS

The International Shark Attack File is kept at the Florida Museum of Natural History in Gainesville. It has cataloged shark attacks from around the world dating back to 1580. The File only catalogs UNPROVOKED attacks. With provoked attacks – those occurring while people are grabbing them, or fishing for them, or in some way provoked an attack – we understand why the shark bit the human. It is the unprovoked attacks that are of more interest. Those where the person was not doing anything intentionally to invite a shark bite, but it happened.

One thing we can tell from this data is that unprovoked attacks are not common. Since 1580, they have logged 3,403 unprovoked shark attacks worldwide. Considering how many people have swum in the ocean since 1580, this is a very small number. Note, the File is only as good as the reports it gets. In the past, many unprovoked attacks were not reported. But in our modern age of communication, it is rare that such an attack does not make the headlines today.

The Bull Shark is considered one of the more dangerous sharks in the Gulf. This fish can enter freshwater but rarely swims far upstream. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Of these attacks 1,640 (48%) have occurred in the United States, followed by 706 in Australia. Many have explained this by the large levels of water activities people in both countries participate in. In the US Florida leads the way with 928 unprovoked attacks (57%), most of these (351 – 34%) are from Volusia County. This may be due to breakthrough emergency communications with Volusia County and thus more reports. Many of the reports are minor, small bites from small sharks such as blacktips, but unprovoked none the less. There are 26 unprovoked attacks logged from the Florida panhandle – 3% of the state total – and most of these (n=9) were from Bay County.

When looking at what people were doing when attacked, most were at the surface and participating in some surface water activity such as surfing, skiing, boogie boarding, etc. This is followed by surface swimming or snorkeling.

This brings us to the attacks this summer in the panhandle. There have been a lot of questions as to what may have caused them. They are still assessing the situation before and during these attacks to try and determine why they happened. As we have mentioned, we have learned a lot about sharks and shark behaviors over the last 50 years and several hypotheses are open for discussion. We will see what the investigators learn. Until then, the International Shark Attack File does offer a page on how you can reduce your risk. There is “Advice to Swimmers”, “Advice to Divers”, “Color of Apparel”, “Menstruation and Sharks”, “Quick Tips”, “Advice to Spearfishers”, and “How to Avoid a Shark Attack”. Read more on these tips at https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/shark-attacks/reduce-risk/.

by Thomas Derbes II | Jun 21, 2024

In Part 1 of The Estuary’s Natural Filtration System article, we discussed the major contributors to natural filtration inside of the estuary. These examples included oysters, marsh plants, and seagrasses. In Part 2, we will discuss the smaller filter-feeding organisms including tunicates, barnacles, clams, and anemones.

Tunicates

Pleated Sea Squirt – Photo Credit: Don Levitan, PH.D. FSU

Tunicates, also known as sea squirts, are very interesting marine invertebrates and can be easily confused for a sponge. There are many different types of tunicates in the estuaries and can be either solitary or colonial. You might’ve seen these at an aquarium attached to different substrates, and when removed from the water, their name sea squirt comes into play. Tunicates have a defense mechanism to shoot out the water inside their body in hopes of being released by any predator.

Tunicates are filter feeders and intake water through their inhalant siphons and expel waste and filtered water through their exhalant siphons. Tunicates can filter out phytoplankton, algae, detritus, and other suspended nutrients. The tunicate produces a mucus that catches these nutrients as it passes through, and the mucus is then conveyed to the intestine where it is digested and absorbed.

An invader to the Gulf of Mexico, the Pleated Sea Squirt (Styela plicata), hitched rides on the hulls of ships and found the Gulf of Mexico waters very favorable. You can sometimes spot these organisms on ropes that have been submerged for a long period of time in salty waters. Even though they are non-native, these sea squirts can filter, on average, 19 gallons of water per day.

Barnacles

Barnacles along the seashore is a common site for many.

Photo: NOAA

One organism that seems ubiquitous worldwide is the barnacle (Genus Semibalanus and Genus Lepas). The Genus Semibalanus contains the common encrusting barnacle we are accustomed to seeing in our waterways along pilings, submerged rocks, and even other animals (turtles, whales, crabs, and oysters). The Genus Lepas contains Gooseneck Barnacles and can be seen attached to flotsam, floating organic debris, and other hard surfaces and have a stalk that attaches them to their substrate. Interesting fact, certain gooseneck barnacle species are eaten in different parts of the world.

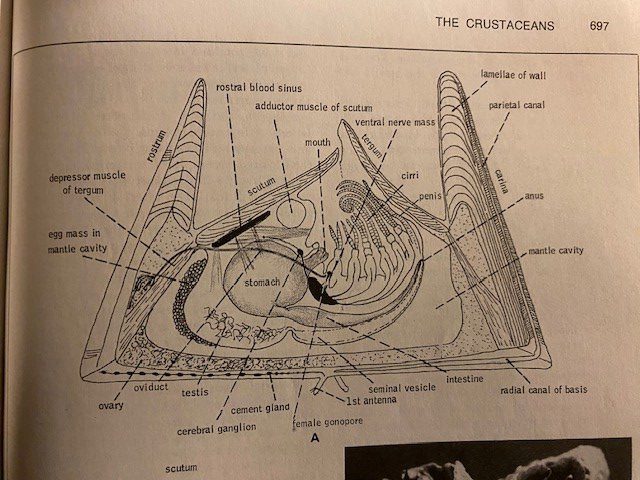

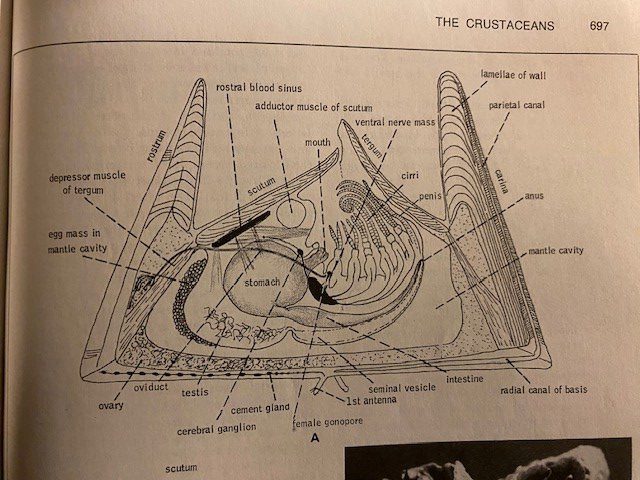

This image from a textbook shows the internal structure of a barnacle. Notice the shrimplike animal on its back with extendable appendages (cirri) for feeding.

Image: Robert Barnes Invertebrate Zoology.

Barnacles have over 2,100 species, are closely related to crabs and lobsters, and are a part of the subphylum Crustacea. At first glance, you might not think a barnacle is closely related to crabs, but when you remove the hard plates surrounding it, the body looks very similar to a crab. Barnacles also have life cycle stages that are similar to crabs; the nauplius and cyprid developmental stages. Inside of the hard plates is an organism with large feather-like appendages called cirri. When covered by water, the barnacles will extend their cirri into the water and trap microscopic particles like detritus, algae, and zooplankton. Barnacles are at the mercy of tides and currents, which makes quantifying their filtering ability difficult.

Hard Clams

Clams of North Florida – UF/IFAS Shellfish

Even though not as abundant in the Florida Panhandle as they were in the 1970’s – 1980’s, hard clams (Mercenaria mercenaria and M. campechiensis) can still be found in the sand along the shoreline and near seagrass beds. These clams are also known as Quahogs and are in the family Veneridae, commonly known as the Venus clam family, and contain over 500 living species. Most of the clams in the family Veneridae are edible and Quahogs are the types of clams you would see in a clam chowder or clam bake.

Being the only bivalve on this list does not make it any less important than the oyster or scallop on Part 1’s list. In fact, a full-grown adult Southern Quahog clam can filter upwards of 20 gallons of water per day and have a lifespan of up to 30 years. Clams also live a much different lifestyle than their oyster and scallop cousins. Clams spend the majority of their life under the sand. Their movement under the sand helps aerate and mix the soil, which can sometimes stimulate seagrass growth.

Right outside the Florida Panhandle and in the Big Bend area, Quahog clams are commercially farmed in Cedar Key. Southern Quahog clams are also being used for restoration work in South Florida. Clams are being bred in a hatchery and their “seed” are being released into Sarasota Bay to help tackle the Red Tide (Karenia brevis) issue. According to the project’s website, they have added over 2 million clams since 2016, and the clams are filtering over 20 million gallons of seawater daily.

Anemones

Tube-Dwelling Anemone Under Dissection Scope – UF/IFAS Shellfish

Anemones are beautiful Cnidarians resembling an upside-down, attached jellyfish, which couldn’t be closer to the truth. The phylum Cnidaria contains over 11,000 species of aquatic animals including corals, hydroids, sea anemones, and, you guessed it, jellyfish. Anemones come in many different shapes and sizes, but the common estuary anemones include the tube-dwelling anemone (Ceriantheopsis americana) and the tricolor anemone (Calliactis tricolor), also known as the hitchhiking anemone. If you have ever owned a saltwater aquarium, you might have run into the pest anemone Aiptasia (Aiptasia sp.).

Anemones filter feed with their tentacles by catching plankton, detritus, and other nutrients as the tide and current flows. The tentacles of the anemone are lined with cnidocytes that contain small amounts of poison that will stun or paralyze the prey. The cnidae are triggered to release when an organism touches the tentacles. If the anemone is successful in immobilizing the prey, the anemone will guide the prey to their mouth with the tentacles. Just like the barnacle, anemones are at the mercy of the tides and currents, and filtration rates are hard to calculate. However, if you ever see an anemone with food around, they move those tentacles to and from their mouths quickly and constantly!

In Parting

As you can see, there are many different natural filters in our estuary. Healthy, efficiently filtering estuaries are very important for the local community and the quality of the waters we love and enjoy. For more information on our watersheds and estuaries and how to protect them, visit Sea Grant’s Guide To Estuary-Friendly Living.

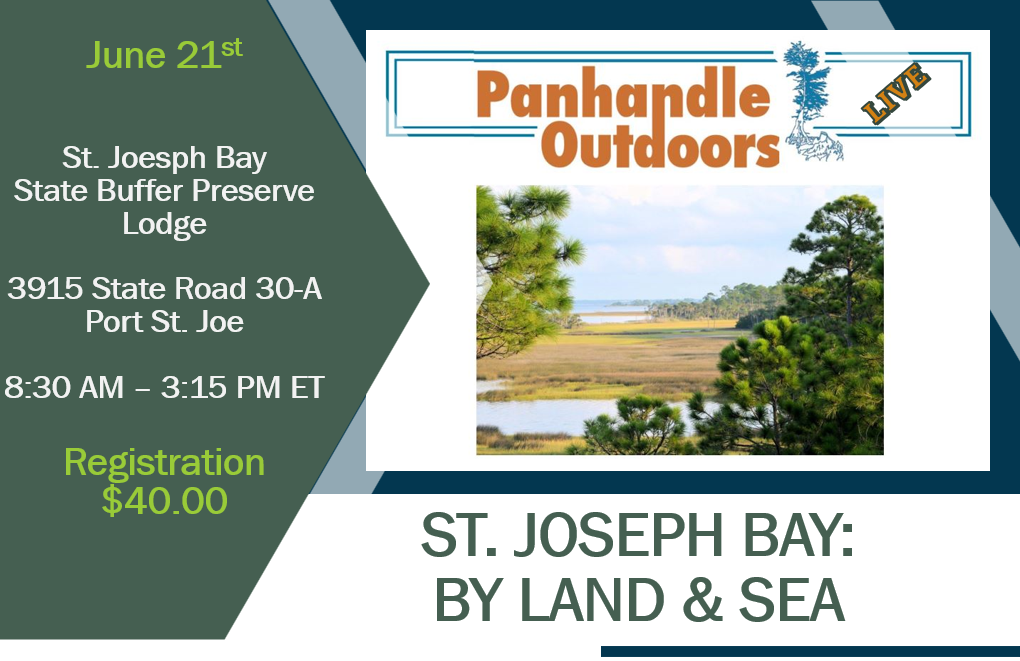

by Ray Bodrey | Jun 3, 2024

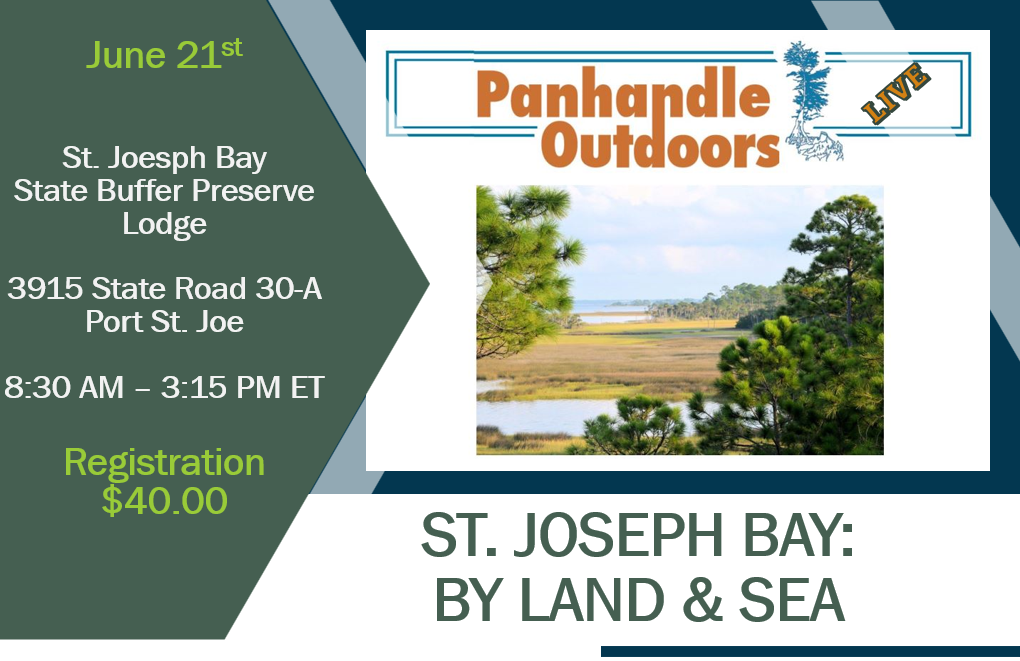

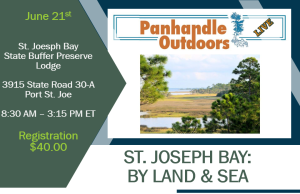

The University of Florida/IFAS Extension & Florida Sea Grant faculty are reintroducing their acclaimed “Panhandle Outdoors LIVE!” series on St. Joseph Bay. This ecosystem is home to some of the richest concentrations of flora and fauna on the Northern Gulf Coast. This area supports an amazing diversity of fish, aquatic invertebrates, turtles and other species of the marsh and pine flatwoods. Come learn about the important roles of ecosystem!

Registration fee is $40. You must pre-register to attend.

Registration link: https://www.eventbrite.com/e/panhandle-outdoors-live-st-joseph-bay-by-land-sea-tickets-906983109897

or use the QR code:

Meals: Lunch, drinks & snacks provided (you may bring your own)

Attire: outdoor wear, water shoes, bug spray and sunscreen

*If afternoon rain is in forecast, outdoor activities may be switched to the morning schedule

Held at the St. Joseph Bay State Buffer Preserve Lodge: 3915 State Road 30-A, Port St. Joe

| 8:30 – 8:35 Welcome & Introduction – Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension (5 min) |

| 8:35 – 9:20 Diamondback Terrapin Ecology – Rick O’Connor, Escambia County Extension |

| 9:20 – 10:05 Exploring Snakes, Lizards & the Cuban Tree Frog – Erik Lovestrand, Franklin County Extension |

| 10:05 – 10:15 Break |

| 10:15 – 11:00 The Bay Scallop & Habitat – Ray Bodrey, Gulf County Extension |

| 11:00 – 11:45 The Hard Structures: Artificial Reefs & Derelict Vessel Program – Scott Jackson, Bay County Extension |

| 11:45 – Noon Question & Answer Session – All Agents |

| Noon – 1:00 Pizza & Salad! |

| 1:00 – 1:20 Introduction to the Buffer & History – Buffer Preserve Staff |

| 1:20 – 2:20 Tram Tour – Buffer Preserve Staff |

| 2:20 – 2:30 Break |

| 2:30 – 3:00 A Walk in the Mangroves – All Agents |

| 3:00 – 3:15 Wrap up & Adjourn – All |

by Carrie Stevenson | May 24, 2024

This tree was downed during Hurricane Michael, which made a late-season (October) landfall as a Category 5 hurricane. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

There are a lot of jokes out there about the four seasons in Florida—instead of spring, summer, fall, and winter; we have tourist, mosquito, hurricane, and football seasons. The weather and change in seasons are definitely different in a mostly-subtropical state, although we in north Florida do get our share of cold weather (particularly in January!).

All jokes aside, hurricane season is a real issue in our state. With the official season about to begin (June 1) and running through November 30, hurricanes in the Gulf-Atlantic region are a legitimate concern for fully half the calendar year. According to records kept since the 1850’s, our lovely state has been hit with more than 120 hurricanes, double that of the closest high-frequency target, Texas. Hurricanes can affect areas more than 50 miles inland, meaning there is essentially no place to hide in our long, skinny, peninsular state.

A disaster supply kit contains everything your family might need to survive without power and water for several days. Photo credit: Weather Underground

I point all these things out not to cause anxiety, but to remind readers (and especially new Florida residents) that is it imperative to be prepared for hurricane season. Just like picking up pens, notebooks, and new clothes at the start of the school year, it’s important to prepare for hurricane season by firing up (or purchasing) a generator, creating a disaster kit, and making an evacuation plan.

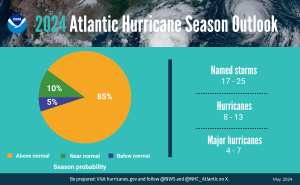

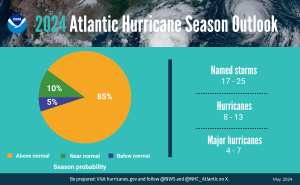

A summary infographic showing hurricane season probability and numbers of named storms predicted from NOAA’s 2024 Atlantic Hurricane Season Outlook. (Spanish version) (Image credit: NOAA)

Peak season for hurricanes is September. Particularly for those in the far western Panhandle, September 16 seems to be our target—Hurricane Ivan hit us on that date in 2004, and Sally made landfall exactly 16 years later, in 2020. But if the season starts in June, why is September so intense? By late August, the Gulf and Atlantic waters have been absorbing summer temperatures for 3 months. The water is as warm as it will be all year, as ambient air temperatures hit their peak. This warm water is hurricane fuel—it is a source of heat energy that generates power for the storm. Tropical storms will form early and late in the season, but the highest frequency (and often the strongest ones) are mid-August through late September. We are potentially in for a doozy of a season this year, too–NOAA forecasters are predicting a very active season, including up to 25 named storms. According to a recent article from Yale Climate Connections, Gulf waters are hotter this May than any year since oceanographers started measuring it in 1981.

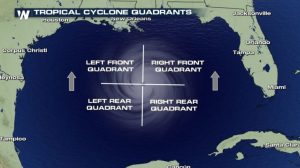

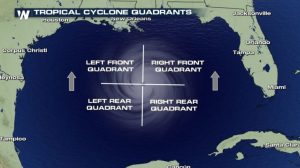

The front right quadrant of a hurricane is the strongest portion of a storm. Photo credit: Weather Nation

If you have lived in a hurricane-prone area, you know you don’t want to be on the front right side of the storm. For example, here in Pensacola, if a storm lands in western Mobile or Gulf Shores, Alabama, the impact will nail us. Meteorologists divide hurricanes up into quadrants around the center eye. Because hurricanes spin counterclockwise but move forward, the right front quadrant will take the biggest hit from the storm. A community 20 miles away but on the opposite side of a hurricane may experience little to no damage.

Flooding and storm surge are the most dangerous aspects of a hurricane. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Hurricanes bring with them high winds, heavy rains, and storm surge. Of all those concerns, storm surge is the deadliest, accounting for about half the deaths associated with hurricanes in the past 50 years. Many waterfront residents are taken by surprise at the rapid increase in water level due to surge and wait until too late to evacuate. Storm surge is caused by the pressure of the incoming hurricane building up and pushing the surrounding water inland. Storm surge for Hurricane Katrina was 30 feet above normal sea level, causing devastating floods throughout coastal Louisiana and Mississippi. Due to the dangerous nature of storm surge, NOAA and the National Weather Service have begun announcing storm surge warnings along with hurricane and tornado warnings.

For helpful information on tropical storms and protecting your family and home, look online here for the updated Homeowner’s Handbook to Prepare for Natural Disasters, or reach out to your local Extension office for a hard copy.