by Rick O'Connor | Nov 6, 2020

Seagrasses have been described as the “nursery of the sea”. Studies show that up to 90% of the commercially valuable fin and shellfish species spend part, or all, of their lives in these submerged meadows. As you can imagine, these grasses must grow in clear, relatively shallow waters – so they are more inshore. You might also imagine that most of the fish living here are going to be small. There are the larger predators in this grassy world, but most are going to be small enough to hide amongst the blades.

These inshore seagrass meadows not only provide hiding places but provide food as well. Interestingly, most do not feed on the grass directly, but rather the tiny plants and animals that are attached to the blades – what are called epiphytes and epizoids. Those that feed on these are then preyed upon by slightly large creatures until we find the larger apex predators – like the speckled trout.

Many of those who reside here are specialist in camouflage and mimicry, and others might be ones who actually live in the sand bordering the edge of the meadows – waiting for a chance to pounce on unsuspecting food. Let’s meet a few of these interesting fish.

Photo: Nicholls State University

Pinfish

You are at the beach for a day of fun and sun. You enter the water of Santa Rosa Sound to play at the edge of the seagrass bed, or maybe to snorkel and explore it. As you stand on the sand you feel little nips at your ankles and immediately think – CRAB! But you would be wrong. As you look closer you will see it came from a small fish – and the more you stir the sand, more of these small fish arrive. They are probably feeding on the small invertebrates that are stirred up from your movement, but they periodically nip at you as well.

This small fish is a very common member of the inshore fish community known as the pinfish. They are members of the Porgy family, related to sheepshead, and have incisor teeth for crushing the shells of their prey. Most locals are first introduced to them as a kid while fishing. They seem to bite, or steal, any bait you put on. Most often used as bait themselves, they are actually edible – but you need one of the large ones to have a meal. They get their common name from the sharp spines of their dorsal fin. When snorkeling in the grassbeds you will find they are the most common fish there.

Photo: USGS

Needlefish

These guys look scarier than they are. Long skinny fish with long skinny snouts that hold long skinny teeth. They resemble barracuda and have the look as if they could attack and do some damage – but they are harmless, unless you catch one in a net, then they will swing their long skinny heads towards your hand for snip.

These small predators travel above the grassbeds looking for potential prey hiding among. Small juvenile fish seem to be what they want. Though often just referred to as “needlefish”, there are actually four species, but they are hard to tell apart.

Photo: NOAA

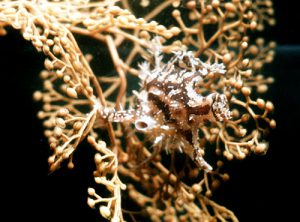

Seahorses

These are captivating fish, and very hard to find as they blend in so well, but they are there – along with their close cousins the pipefish. It seems hard to call it a fish at all – it certainly does not look like one. Swimming vertically in the water, no tail to speak of, they seem like a creature in their own group. But they are fish. The scales are fused into an armor plating and they do have both gills and fins – characteristics of fish. They will use their prehensile tail to grab onto a grass blade, hanging there waiting for tiny shrimp to swim by which they inhale using a vacuum like motion with their tube-shaped mouths.

Pipefish resemble seahorses but are elongated, with a distinct fin for a tail, and swim horizontally as most fish do. They will turn vertically in the grass to appear to be a blade themselves and hunt similar prey as their seahorse cousins.

A well-known characteristic of this group is the fact that the males carry the fertilized eggs – not the females. Males can be identified by the brood sac on their ventral side and they may carry up to 80 eggs. The eggs hatch within the pouch and the young are born alive.

Photo: NOAA

Puffers

This group of fish are famous for their ability to “blow up”, or inflate like a balloon, when threatened. Kids love to play with them and get a kick out of watching them inflate. These are round bodied – slow moving fish, which is one reason they inflate. It does not matter if you can catch them, you cannot swallow them if you do!

There are actually two different families of “blowfish”. The true puffers are smaller (3-12 inches), have tubercles on their bodies instead of long spines, and the teeth in the upper and lower jaw have a space forming four teeth (two on the top jaw, two on the bottom) – giving them their family name “tetradontidae”. The “burrfish” are larger in size (1-2 feet), have long spines on the body, and no median in the teeth – so only one tooth on the top jaw, one on the bottom – “diodontidae”.

The most common one found is the striped burrfish. The big boy of the group – the 2-foot porcupine fish – is rare in the northern Gulf and prefers the reefs of the open sea to grassbeds.

When threatened they will inflate with water (or air) and try to continue swimming. After the danger has passed, they will deflate and go about their merry way. There are stories about their flesh being poisonous and dangerous to eat – it is true. The compound they produce is one of the more toxic found in the fish world. Though there are certified chefs around the world who can safely clean them, it is not recommended you eat these.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 16, 2020

When most people think of reefs, they think of the coral reefs of the Florida Keys and Australia. But here in the northern Gulf the winters are too cold for many species of corals to survive. Some can, but most cannot and so we do not have the same type of reefs here.

That said, we do have reefs. We have both natural and artificial reefs. There are natural reefs off Destin and a large reef system off the coast of Texas – known as the “Flower Gardens”. Here the water temperatures on the bottom are warm enough to support some corals. The artificial reef program along the northern Gulf is one of the more extensive ones found anywhere. There is a science to designing an artificial reef – you do not just go out and dump whatever – because if not designed correctly, you will not get the fish assemblages and abundance you were hoping for. But if you do… they will come.

Reefs are known for their high diversity and abundance of all sorts of marine life – including fishes. There are numerous places to hide and plenty of food. Most of the fish living on the reef are shaped so they can easily slide in and out of the structure, have teeth that can crush shell – the parrotfish can actually crush and consume the coral itself, and some can be fiercely territorial. There are numerous tropical species that can be found on them and they support a large recreational diving industry. Let’s look at a few of these reef fish.

Moray eel.

Photo: NOAA

Moray Eels

These are fish of legend. There all sorts of stories of large morays, with needle shaped teeth, attacking divers. Some can get quite large – the green moray can reach 8-9 feet and weigh over 50 pounds. Though this species is more common in the tropics, it has been reported from some offshore reefs in the northern Gulf. There are three species that reside in our area: the purplemouth, the spotted, and the ocellated morays. The local ones are in the 2-3 foot range and have a feisty attitude – handle with care – better yet… don’t handle. They hide in crevices within the reef and explode on passing prey, snagging them with their sharp teeth. Many divers encounter them while searching these same crevices for spiny lobster. There are probing sticks you can use so that you do not have to stick your hand in there. There are rumors that since they have sharp teeth and tend to bite, they are venomous – this is not the case, but the bite can be painful.

The massive size of a goliath grouper. Photo: Bryan Fluech Florida Sea Grant

Groupers

This word is usually followed by the word “sandwich”. One of the more popular food fish, groupers are sought by anglers and spearfishermen alike. They are members of the serranid family (“sea basses”). This is one of the largest families of fishes in the Gulf – with 34 species listed. 15 of these are called “grouper” and there have been other members of this family sold as “grouper”.

So, what is – or is not – a “grouper”. One method used is anything in the genus Epinephelus would be a grouper. This would include 11 species, but would leave out the Comb, Gag, Scamp, Yellowfin, and Black groupers – which everyone considers “grouper”. Tough call eh?

These are large bodied fish with broad round fins – the stuff of slowness. That said, they can explode, just like morays, on their prey. Anglers who get a grouper hit know it, and divers who spear one know it. They range in size from six inches to six feet. The big boy of the group is the Goliath Grouper (six feet and 700 pounds). They love structure – so natural and artificial reefs make good homes for them. They also like the oil rigs of the western Gulf.

An interesting thing about many serranids is the fact they are hermaphroditic – male and female at the same time. Most grouper take it a step further – they begin life as females and become males over time.

The king of finfish… the red snapper

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

Snappers

The red snapper is king. Prized as a food fish all over the United States, and beyond, these fish have made commercial fishermen very happy. With an average length of 2.5 feet, some much larger individuals have been landed. This fishery put Pensacola on the map in the early 20th century. Sailing vessels called “Snapper Smacks” would head out to the offshore banks and natural reefs, return with a load, and sell both locally and markets in New York. There are large populations in Texas waters and down on the Campeche Banks off Mexico. “Snapper Season” is a big deal around here.

Though these are reef fish, snapper have a habit of feeding above, and away from, them. You probably knew there was more than one kind of snapper but may not know there are 10 species locally. Due to harvesting pressure, there are short seasons on the famous red snapper – so vermillion snapper has stepped in as a popular commercial fishery – and it is very good also. Some, like the gray snapper, are more common inshore around jetties and seawalls. Also known as the black snapper or mangrove snapper, this fish can reach about three feet in length and make a good meal as well.

The white grunt.

Photo: University of Florida

Grunts

Grunts look just like snapper, and probably sold as them somewhere. But they are a different family. They lack the canines and vomerine teeth the snappers have – other than that, they do look like snapper. Easy to tell apart right? Vomerine are tiny teeth found in the roof of the mouth, in snappers they are in the shape of an arrow. They get their name from a grunting sound they make when grinding their pharyngeal teeth together. A common inshore one is called the “pigfish” because of this. They do not get as large as snapper (most are about a foot long) and are not as popular as a food fish, but the 11 known species are quite common on the reefs, and the porkfish is one of the more beautiful fish you will see there.

Spadefish on a panhandle snorkel reef.

Photo: Navarre Beach Snorkel

Spadefish

This is one of the more common fish found around our reefs. Resembling an angelfish, they are often confused with them – but they are in a family all to themselves. What is the difference you ask? The dorsal fin of the spade fish is divided into two parts – one spiny, the other more fin-like. In the angelfish, there is only one continuous dorsal fin.

Spadefish like to school and are actually good to eat. It is also the logo/mascot of the nearby Dauphin Island Sea Lab.

Gray triggerfish.

Photo: NOAA

Triggerfish

“Danger Will Robinson!” This fish has a serious set of teeth and will come off the reef and bite through a quarter inch wetsuit to defend their eggs. Believe it – they are not messing around. Once considered a by-catch to snapper fishermen, they are now a prized food fish. They are often called “leatherjackets” due to their fused scales forming a leathery like skin that must be cut off – no scaling with this fish. They have the typical tall-flat body of a reef fish, squeezing through the rocks and structure to hide or hunt. We have five species listed in the Gulf of Mexico, but it is the Gray Triggerfish that is most often encountered.

Photo courtesy of Florida Sea Grant

Lionfish

You may, may not, have heard of this one – most have by now. It is an invader to our reefs. To be an invasive species you must #1 be non-native. The lionfish is. There are actually about 20 species of lionfish inhabiting either the Indo-Pacific or the Red Sea region.

#2 have been brought here by humans (either intentionally or unintentionally – but they did not make it on their own) – this is the case with the lionfish. It was brought here for the aquarium trade. There are actually two species brought here: The Red Lionfish (Pterois volitans) and the Devilfish (Pterois miles). Over 95% of what has been captured are the red lionfish – but it really does not matter, they look and act the same – so they are just called “lionfish”.

#3 they must be causing an environmental, and/or an economic problem. Lionfish are. They have a high reproductive rate – an average of 30,000 offspring every four days. There is science that during sometimes of the year it could be higher, also they breed year-round. Being an invasive species, there are few predators and so the developing young (encapsulated in a gelatinous sac) drift with the currents to settle on new reefs where they will eat just about anything they can get into their mouths. There have been no fewer than 70 species of small reef fish they have consumed – including the commercially valuable vermillion snapper and spiny lobster. There is now evidence they are eating other lionfish.

They quickly take over a reef area and some of the highest densities in the south Atlantic region have been reported off Pensacola. However, at a 2018 state summit, researchers indicated that the densities in our area have declined in waters less than 200 feet. This is most probably due to the harvesting efforts we have put on them. They are edible – actually, quite good, and there is a fishery for them. Derbies and ecotours have been out spearfishing for them since 2010. You may have heard they were poisonous and dangerous to eat. Actually, they are venomous, and the flesh is fine. The venom is found in the spines of the dorsal, pelvic, and anal fins. It is very painful, but there are no records of anyone dying from it. Work and research on management methods continue.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 2, 2020

Is this what it sounds like? Fish that do not swim, but drift? Well… yes and no. They can swim, just not very well – they do better by drifting.

The word used most often for any drifting creature in the sea is plankton. Plankton literally means “drifter” or “wanderer”. Most plankton, including planktonic fish, can swim. Some can adjust their position in the water column – rising near the surface at night, sinking deeper during the day.

When you think about it, it is a cool way to make a living out there. With miles and miles of open blue water, the swimming fish must keep swimming. To do this requires a lot of energy, open water fish must consume a lot of high energy food. Drifters just drift. Hang with the currents, enjoying the moment, eating what they can. Sounds pretty good huh?

As you can imagine, there are not many fish who live this lifestyle. Many do after they hatch in their larval stage – but as adults, most live on the bottom, others in the open blue. Let’s meet a couple of the drifters.

The slow moving ocean sunfish.

Photo: NOAA

Sunfish

Now here is one weird looking fish. Large bulbous head, long angular dorsal and ventral fins, and no tail – it’s a swimming/drifting head. These large open water drifters can reach seven feet long, seven feet high, and weigh over a ton. They can hold their position, undulating their dorsal and ventral fins, and move slowly through the water. Often, they will turn on their sides and just hang there. Looking like a floating board or something, small creatures are attracted to them, some of which they eat. Their diet is primarily jellyfish, though they have been known to take small fish, crustaceans, and even algae.

They are related to puffer fish, and actually resemble them early in life, but the resemblance fades quickly as this becomes more head than anything else.

Though rarely seen near shore, they have been, and one was actually spotted inside Pensacola Bay. They occasionally wash ashore dead. One did on Dauphin Island. The staff at the Sea Lab made a mold of the dead creature which is now hanging in the public Estuarium there. Many know this fish by its scientific name – Mola mola – or simply “the mola”. It is a pretty cool fish.

https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/ocean-sunfish/

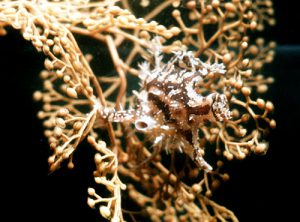

This sargassum fish is well camouflaged within this mat of sargassum weed.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

Sargassum Fish

Sargassum fish are members of a family known as “frogfish” – so you can guess what they must look like – and can guess they are not real good swimmers. Almost completely round, they are blobs in the sea. There are three species in the Gulf, two if which are bottom fish. However, the Sargassum fish is a drifter – drifting with the common seaweed known by its scientific name Sargassum. Sargassum is brown algae that produces air bladders called pneumatocyst. These bladders allow the weed to drift in large mats at the surface where they get sunlight. Some sargassum mats are huge is size and are an ecosystem amongst themselves. Hundreds of miniature fish and invertebrates call this place home – a place to hide in the open sea. It is the home of baby sea turtles, if they can make the trek from the beach alive.

One member of this community is the Sargassum fish (Histrio histrio). It has the typical frogfish shape and look but the coloration matches the Sargassum weed perfectly. Like other frogfish, the first dorsal spine is modified into a “fishing rod” complete with a “lure”. When prey (small creatures in the Sargassum weed) are in view, the Sargassum fish will extend the illicium (as it is called) and actually move it back and forth to make it look like live bait – they are fishing.

Most members of the Sargassum community flee the weed when the currents bring it to close to the beach. However, they hang on longer than you might think. If you are at the beach when the Sargassum is drifting just off the shore – wade out with a small kids dip net and snag a patch. Place in a bucket and see who comes out. You MIGHT get lucky and catch one of these ocean drifters.

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 11, 2020

There is a lot of blue out there… a whole lot of blue. Miles of open water in the Gulf with nowhere to hide… except amongst yourselves. Their blue colored bodies, aerodynamically shaped like bullets with stiff angular fins, can zip along in this vast blue openness in large schools. Their myoglobin rich red muscle increases their swimming endurance – they can travel thousands of miles without tiring. Some species are what we call “ram-jetters”, fish that basically do not stop swimming – roaming the “big blue” looking for food and avoid being eaten, following the warm currents in search of their breeding grounds.

The open water is a place for specialists. Most of these fish have small, or no scales, to reduce frictional drag. They have a well-developed lateral line system so when a member of the school turns, the others sense it and turn in unison – just as the four planes in the US Navy Blue Angels delta do – perfect motion.

Many are built for speed. Sleek bodies with sharp angular fins and massive amounts of muscle / body mass, some species can reach speeds close to 70 mph – some can “fly”. There are fewer species who can live here, as opposed to the ocean floor, but those who do are amazing – and some of the most prized commercial and recreational fishing targets in the world. Let’s meet a few of them.

Flying fish do not actually “fly”, they are gliders using their long pectoral fins.

Photo: NOAA

Flying Fish

First, they do not actually fly – they glide. These tube-shaped speedy fish have elongated pectoral fins, reaching half the length of their bodies. The two lobes of their forked tail are not the same length – the lower lobe being longer. Using this like a rudder, they gain speed near the surface and, at some point, leap – extend the large pectoral fins, and glide above the water – sometimes up to 100 yards. As you might guess, this is to avoid the sleek speedy open water predators coming after them. You might also imagine that they, and their close cousins the half-beaks, are popular bait for the bill fishermen seeking those predators.

There are eight species of these amazing fish in the Gulf of Mexico ranging in size from 6-16 inches. Most are oceanic – never coming within 100 miles of the coast, but a few will, and can, be seen even near the pass into Pensacola Bay.

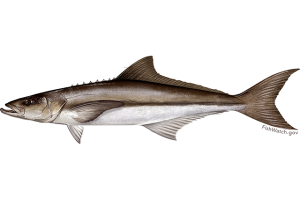

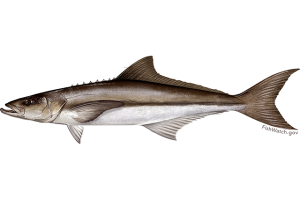

The cobia – also known as the ling, lemonfish, and sergeant fish, is a migratory species moving through our area in the spring.

Image: NOAA

Cobia

This is one of the migrating fish local anglers gear up for every year – the cobia run. When the water turns from 60° to 70°F in the spring – the cobia moves up the coastline heading from east to west. They have many different common names along the Gulf Coast. Ling, Cabio, Lemonfish, and Sergeant fish have all been used for this same animal. This is one reason biologists use scientific names – Rachycentron canadum in this case. That way we all know we are talking about the same fish. Whatever you call it, it is popular with the anglers and there is nothing like a fresh cobia sandwich – try one!

They can get quite large – 5 feet and up to 100 pounds – and resemble sharks in the water, sometimes confused with them. They seem to like drifting flotsam, where potential prey may hangout, and fishermen will toss their baits all around their schools trying to get them to take. At times, fishermen have confused sea turtles with cobia and have accidentally snagged them – only to release it, though it is a workout to do so, and they try to avoid it.

Cobia are in a family all their own. Their closest relatives are the remoras, or sharksuckers, which sometimes attach to them. They travel all over the Gulf and Atlantic Ocean.

Jacks have the sleek, fast design of the typical open water marine fish.

Photo: NOAA

Jacks

This is the largest open water family of fish I the northern Gulf – with 24 species. Not all jacks are open water, many are found on reefs and in estuaries. But these are aerodynamic shaped fish, with small scales and angular fins, and built for the open water environment. They vary in size, ranging from less than one foot, to over three. This group is identified by the two extended spines just in front of their anal fin. Several species – such as the amberjacks, pompano, and almaco jacks – are prized food fish. Others – like the jack crevalle and the blue runner (hardtail) – are just fun to catch, putting up great fights.

They are schooling fish and often associated with submerged wrecks and reefs, where prey can be found. The black and white pilot fish is called this because mariners would see them swimming in front of sharks – “piloting” them through the ocean. They are open water jacks but are more tropical and accounts in our area are rare.

The colors of the mahi-mahi are truly amazing.

Photo: National Wildlife Federation

Mahi–Mahi

This is the Hawaiian term for a fish called the dolphin (Coryphaena hippurus). You can probably guess why they prefer to call it by its Hawaiian name. It is a popular food fish, and to have “dolphin” on the menu – or to say “hey, we’re going dolphin fishing – want to come?” would raise eyebrows – and have.

The Mexicans call it “dorado”, and that term is used locally as well. Either name – it is an amazing fish. With the bull-shaped forehead of the males – they are sometimes referred to as the “bull-dolphin”. Their colors, and color changing, is amazing to see. Some biologists believe this may be some form of communication between members, don’t know, but the brilliant greens, blues, and yellows are amazing to see. They lose these colors shortly after death, so you must see it to believe it – or find one of the popular fish t-shirts.

Like jacks, dolphin like to hang around flotsam, or large schools of baitfish, looking for prey. As with many other open water predators, they will sometimes work in a team to scare, and scatter, individuals from the safety of their school. There are only two species in this family, and both are prized for their taste.

The Striped Mullet.

Image: LSU Extension

Mullet

This is not one you would typically call an “open water” fish. But in the nearshore Gulf and estuaries, they are more open water than bottom dwellers – though they do feed off the bottom. Sleek bodied, forked tail, angular fins, they have what it takes to be a fast swimmer. Though they do not “fly” as the flying fish do, they do leap out of the water. Many visitors hanging out around the Sound will hear a fish splash and immediately ask “what kind of fish was that?” Many locals will respond without looking up – “it was a mullet” – and they are probably right.

This brings up the age-old question… why do mullet jump? This was once asked of a marine biology professor. He paused… thought… and responded saying “for the same reasons manta rays jump”. That was it… another long pause. Finally, the students “took the bait” – “Okay, why do manta rays jump?”. The professor replied, “we don’t know”. So, there you go.

Another interesting thing about this fish is its wide tolerance of salinity. Mullet have been found in freshwater rivers and springs and the hypersaline lagoons of south Texas – they truly don’t care.

Locally they are popular food fish, and support a large commercial fishery in Florida, but in other parts of the Gulf not so much. It has to do with their environment and what they are feeding on. In muddier portions of the Gulf (or our bay for that matter) they have an oily taste and locals there call the “trash fish”. Even hearing that locals here eat them “grosses” them out. Local respond by giving it a more “high end” name – the Mulle (spoken with a French accent). This is actually the Cajun term for the fish. And let’s step it up a notch by adding that many locals eat mullet row – the eggs. Yea… getting hungry right? One of the popular cable food shows came here to try mullet roe. They said on a scale of 1 to 10, they give it a -4.

All that said, it is a local icon – with seafood stores selling “In Mullet We Trust” t-shirts, and the popular “Mullet Toss” event held every year on Perdido Key. It is a COOL fish.

This Spanish Mackerel has the distinct finlets of the mackerel family along the dorsal and ventral side of the body.

Image: NOAA

Mackerel

When you mention mackerel around here you usually think of one of two fish – the king mackerel (sometimes just referred to as “the king”) and the Spanish mackerel. But it is actually a large family of open water fish that includes the tuna, bonito, and the wahoo (of baseball fame).

They are some of the fastest fish in the sea, and several species are ram-jetters. Sleek bodies, sharp angular fins, they can be identified by the row of small finlets on the dorsal and ventral sides of their bodies near the rear. Full of red muscle, rich in myoglobin (which can hold more oxygen than hemoglobin alone), these are powerful swimming fish and very popular in the sushi trade. A bluefin tuna can be 14 feet long, 800 pounds, and bring a commercial fisherman tens of thousands of dollars. Because of this bluefin tuna are internationally protected and managed.

Another cool thing about these guys is that some species can control blood flow, and location, to help maintain a higher body temperature – “warm blooded” – allowing them to venture into colder waters of the world’s oceans. They are one of the big migratory fish we find. Following the large ocean currents, some species use this to play out their entire life cycle. Born in the warmer portions of the ocean gyres, they grow and feed in the cooler areas, returning in the warmer currents to breed.

There are 12 species in this family ranging in size from 1 to 15 feet. They have the characteristic “dark on top – light one bottom” coloration many animals have. This called countershading. It is believed to be used as a form of camouflage in the deep blue – with the darker blue-indigo on top (to blend in with the bottom if look from above) and the lighter silver-white on the bottom (to blend in with the sunlit surface if viewed from the below). This idea was used by the US Navy during World War II. If you visit our Naval Aviation Museum, you will see they painted the planes a darker blue on top and a lighter white on bottom. In hopes that the Japanese pilots would have a hard time spotting them over the Pacific Ocean. It is also believed to help with temperature control. The darker side will absorb heat, while the lighter side releases – avoiding over-heating. Amazing fish, aren’t they?

by Rick O'Connor | Sep 3, 2020

We continue our series on estuarine and marine fish and wildlife with fish who live on the bottom.

This longnose killifish has the rounded fins of a bottom dwelling fish.

The Gulf of Mexico is a huge ecosystem. With 600,000 m2 and an average depth of 6000 feet, there is a lot of “blue” out there for fish to find a home. But oddly enough, 69% of the species describe in the northern Gulf live on the bottom – what we call benthic fish.

This makes since really. In the “open blue” there are few places to hide from predators and prey. On the other hand, the seafloor has numerous places to hide – so there they are.

Most benthic fish have a general body design for living there. They are generally deep bodied, more rounded – as are their fins. They have a higher percentage of white muscle which makes them very explosive – for a few seconds. This is how they live. Blending in with the bottom, waiting for the prey to get within range and then exploding on it. This white muscle also gives these fish a distinctive taste, different from the red muscle typically found in the open water fish such as tuna.

In this environment, the sense of smell is very good. Many have taste and smell buds extended on fleshy appendages called barbels (the “whiskers” of a catfish). Many will have their mouth on the bottom side of their head for easier eating – though the predators (like the grouper) will still have it directly in front. Many will make short migrations into estuaries for breeding, but long open ocean migrations are not common. There are 342 species of benthic fish in the northern Gulf, let’s look at a few.

The Anguilla eel, also known as the “American” and “European” eel.

Photo: Wikipedia.

Eels

Something about these animals creeps us out. Maybe their similarity to snakes? Maybe the thought they are electric or venomous – neither of which are true. There are electric eels in the Amazon, but not in the ocean. They do behave much like snakes in that they have very sharp teeth for grabbing prey and can use them on fishermen if they need to. There are 16 species of eels in the northern Gulf. With the exception of the morays – eels live in sandy or muddy bottoms. Shrimpers frequently haul them up, and some are even known as shrimp eels. The American eel (Anguilla rostrata) has a cool life history. They spawn in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, a place known to the sailors as the Sargasso Sea. It is in the middle of the vortex of ocean currents. The young that catch the northern currents and head to Europe – there they are known as the “European Eel”. Those that catch the southern swirl end up here in the United States are known as the “American Eel”. Their young look like thin pieces of plastic with eyes. Known as elvers they can be found within Pensacola Bay by the thousands when they arrive. The growing adults move up stream and spend part of their lives in our rivers and springs, before swimming back to the Atlantic and starting the process all over. In some areas, there is a commercial fishery for this eel.

Read more:

https://fws.gov/fisheries/freshwater-fish-of-america/american_eel.html.

https://www.fws.gov/fisheries/fishmigration/american_eel.html.

The serrated spines and large barbels of the sea catfish. Image: Louisiana Sea Grant

Catfish

This is a bottom fish that fishermen love to hate. Marine catfish (Ariopsis felis) are oily and not as popular as their freshwater cousins as food. So, when fishermen catch them, they tend to toss them on the beach to die – the idea is that there are fewer to breed – an idea that really does not work – they keep catching them. One interesting twist on this story is that the ghost crabs in the dunes drag the dead ones towards their burrows where they feed on them. The skull of the sea catfish is very hard – giving them their other common name “hardhead” catfish, or “steelhead”. When the crabs are finished the hard skull can be found and the bones on the belly (ventral) side resemble the cross. It is sold in some novelty stores as the “crucifix fish”. To add to the legend, when you shake it, it rattles. This has been described at the “soldiers rolling dice” at the crucifixion. They are actually loose bones. These “crucifix fish” are pretty neat, and pretty common.

The long “whiskers” (barbels) are for finding food buried beneath the sand or mud. It is also believed they may have a form of echolocation to detect prey. As if this were not interesting enough – the males carry the developing eggs within their mouths. Development takes about two weeks and young fish emerge from dad ready for the world.

One other thing the visitor should know – the serrated spine on the dorsal and the pectoral fins can inflict a nasty wound, even releasing a mild toxin. Most discover this when they step on a dead one tossed on the beach, or trying to get one off their hook – be careful of this.

Read more:

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hardhead_catfish.

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/hardhead.catfish.php.

https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/269847.

The classic look of a bottom fish. This is the redfish, or red drum.

Photo: NOAA

Drum–Croaker

This is the largest family of estuarine fish in the northern Gulf of Mexico – with 18 species described. The whiting, drum, kingfish, croakers, trout, some perch, and others all belong to this group. They are popular with fishermen and seafood consumers. The red drum (redfish) is one of the more popular targets in our area. Speckled trout (or spotted seatrout) are also a favorite. Most have the characteristic body of a benthic fish. Deep bodied, rounded fins, mouth on the belly (ventral) side. Sea trout have two large “Dracula” looking fangs for grabbing shrimp and other prey. In most, one has broken off and the angler usually finds only one fang present. Some species, such as the black drum, will have short “whiskers” on their chins – you guessed it, barbels – and they are used for finding “buried treasure” (food).

Their common name drum (or croaker) comes from the sounds they produce using their swim bladders. Swim bladders are large sacs within many fish they can fill with gas and float off the bottom. The drum-croaker group rub this with internal muscles making resonating sounds that sound like they are “croaking”. Atlantic bottlenose dolphin can hear this too – and croakers make up a big part of their diet.

Read more:

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/red.drum.php.

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/spotted.seatrout.php.

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/southern.kingfish.php

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/sand.seatrout.php

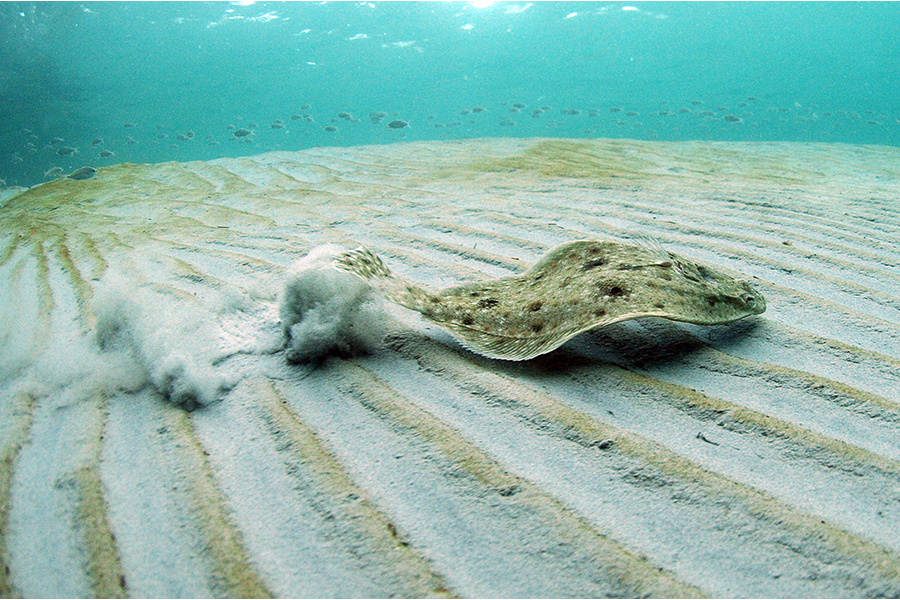

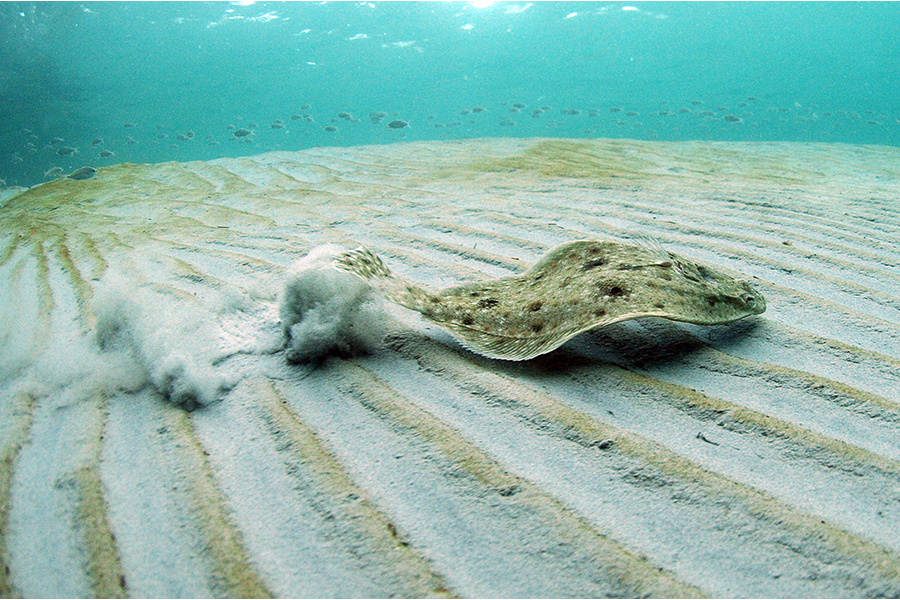

A flounder scurrying across the seafloor.

Photo: NOAA

Flounder

There are actually two types of flatfish in the Gulf – the flounder and the sole. How do you tell them apart?

Well, they are born as a typical-normal looking fish, but as they grow one eye begins to “slide” across the top of the head to the other side – both eyes are now on one side of the head – weird right?

In our part of the Gulf, if the eyes slide to the left side – we call it a flounder, to the right – a sole. There are a FEW exceptions to this rule – but many call the popular flounder the “left-eyed flounder” as opposed to the “right-eyed” one.

So why do they do this?

If your eyes were placed on each side of a torpedo pointed head, you would have what we call monocular vision. This type of vision gives you ALMOST 360° range of view… almost. So even though you can see what is behind you while facing forward, you do not have good depth perception – so you are not sure exactly how far away it is. You must either rely on other senses to help you out or get lucky. Having both eyes on one side (or in front like us) you have binocular vision. You cannot see behind you, but you can tell the distance of the object in front of you. This is common for predator fish like flounder. Many would agree that your mother has both!

With the eyes on one side of the head, they lose color on the other and then lay flat on one side. They can bury in sand and wait for prey. Most species have chromatophores in their skin. These are cells that allow them to change color, like a chameleon or octopus. So, they can change their color to blend into whatever bottom type they are on. What an incredible adaptation.

There are 17 species of flounder, and they are not easy to tell apart – so just call them flounder.

Read more:

http://gcrl.usm.edu/public/fish/flounder.php.