by Andrea Albertin | Aug 27, 2021

Prepare an emergency drinking water supply for your household before a storm hits. Image: Tyler Jones, UF/IFAS.

Storm season is upon us. During a natural disaster, normal drinking water supplies can quickly become contaminated. To be prepared, collect and store a safe drinking water supply for your household before a storm arrives.

How much water should be stored?

- Store enough clean water for everyone in the household to use 1 to 1.5 gallons per day for drinking and personal hygiene (small amounts for things like brushing teeth). Increase this amount if there are children, sick people, and/or nursing mothers in the home. If you have pets, store a quart to a gallon per pet per day, depending on its size.

- Store a minimum 3-day supply of drinking water. If you have the space for it, consider storing up to a two-week supply.

- For example, a four-person household requiring 1.5 gallons per person per day for 3 days would need to store 18 gallons: 4 people × 1.5 gallons per person × 3 days = 18 gallons. Don’t forget to include additional water for pets!

What containers can be used to store drinking water?

Store drinking water in thoroughly washed food-grade safe containers, which include food-grade plastic, glass containers, and enamel-lined metal containers, all with tight-fitting lids. These materials will not transfer harmful chemicals into the water or food they contain.

More specific examples include containers previously used to store beverages, like 2-liter soft drink bottles, juice bottles or containers made specifically to hold drinking water. Avoid plastic milk jugs if possible because they are difficult to clean. If you are going to purchase a container to store water, make sure it is labeled food-grade or food-safe.

As an extra safety measure, sanitize containers with a solution of 1 teaspoon of non-scented household bleach per quart of water (4 teaspoons per gallon of water). Use bleach that contains 5%–9% sodium hypochlorite. Add the solution to the container, close tightly and shake well, making sure that the bleach solution touches all the internal surfaces. Let the container sit for 30 seconds and pour the solution out. You can let the container air dry before use or rinse it thoroughly with clean water.

Best practices when storing drinking water

- Store water away from direct sunlight, in a cool dark place if possible. Heat and light can slowly damage plastic containers and can eventually lead to leaks.

- Make sure caps or lids are tightly secured.

- Store smaller containers in a freezer. You can use them to help keep food cool in the refrigerator if the power goes out during a storm.

- Keep water containers away from toxic substances (such as gasoline, kerosene, or pesticides). Vapors from these substances can penetrate plastic.

- When possible, use water from opened containers in one or two days if they can’t be refrigerated.

- Although properly stored public-supply water should have an indefinite shelf life, replace every 6-12 months for best taste.

More information on preparing an emergency drinking water supply can be found on the CDC website and in the EDIS Publication ‘Preparing and Storing an Emergency Safe Drinking Water Supply‘

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 8, 2021

Well-maintained stormwater ponds can become attractive amenities that also improve water quality. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Prior to joining UF IFAS Extension, I spent three years as a compliance and enforcement field inspector with the local Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) office. It was a crash course in drinking water regulation, wetlands ecology, stormwater engineering, and human psychology. For about half of that time, I worked in the stormwater section with an engineer, certifying the proper construction and specifications of stormwater treatment ponds built for residential and commercial developments. During a construction boom in 2000-2003, my coworkers and I traversed back roads from Perdido Key to Freeport, trying to catch every new project and make sure it was done right. If they weren’t, it also fell to the 3 of us to make sure mistakes were corrected.

Since 1982, Florida Statutes have required that rainfall landing on newly constructed impervious surfaces (rooftops, streets, parking lots, etc.) must be treated before turning into runoff that leaves the property and ends up in local water bodies. The pollutants in stormwater runoff—heavy metals, fertilizer, pesticides, trash, bacteria, and sediment—are the biggest sources of water quality problems for the state, more so even than industrial and agricultural sources.

The most common stormwater ponds have sandy bottoms, grassed berms, and piped inlets with riprap to slow the influx of water. Photo credit, Michelle Diller

Therefore, new developments are required to treat that runoff. This may be accomplished by several means, including regional stormwater ponds. However, the most common are still curbs and gutters, which drain to an often-rectangular hole in the ground with a chain-link fence around it. Ideally, water pools into these dry ponds while raining, reducing flood risk and holding water long enough to allow it to soak into the soil. Most of the ponds in northwest Florida have sandy bottoms that percolate easily. Maintenance is required, however, and when heavier soils, trash, or muck accumulate they must be cleaned out to function properly. Depending on the geology of any given location, the ponds may need sand filters or “chimneys” added to allow water to soak into the native soil.

Admiral Mason Park, adjacent to the Veterans’ Memorial Park along Pensacola Bay, is an example of a regional City stormwater treatment facility that also serves as a park. Photo credit: Visit Pensacola

If an area is naturally low-lying, close to the water table, or has highly organic, water-holding soils, it may be necessary to construct a “wet” stormwater pond. In these, water stands to a level below an overflow device, and can become a water feature for the development. Many residential developers will sell lots around a stormwater pond as “waterfront property” and a well-maintained one really can be a nice amenity. However, at their core, these are stormwater treatment mechanisms. A wet pond functions differently than a dry one and is dependent on healthy stands of shoreline vegetation to take up extra nutrients, metabolize them, and render them into harmless compounds. Many of these ponds have fountains to aerate the water and keep them from becoming stagnant. The City of Pensacola and Escambia County have several great examples of these types of ponds that serve as regional stormwater detention and community amenities. These were constructed in lower-lying areas to handle chronic problems with stormwater in areas that were built up and paved many decades before stormwater rules came into effect. Many other innovative and newer stormwater treatments exist as well, including bioretention, rainwater harvesting, green roofs, and pervious pavement.

by Andrea Albertin | Oct 9, 2020

Special care needs to be taken with your septic system after flooding. Image: B. White NASA. Public Domain

During and after floods or heavy rains, the soil in your septic system drainfield can become waterlogged. For your septic system to treat wastewater, water needs to drain freely in the drainfield. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system under flood conditions.

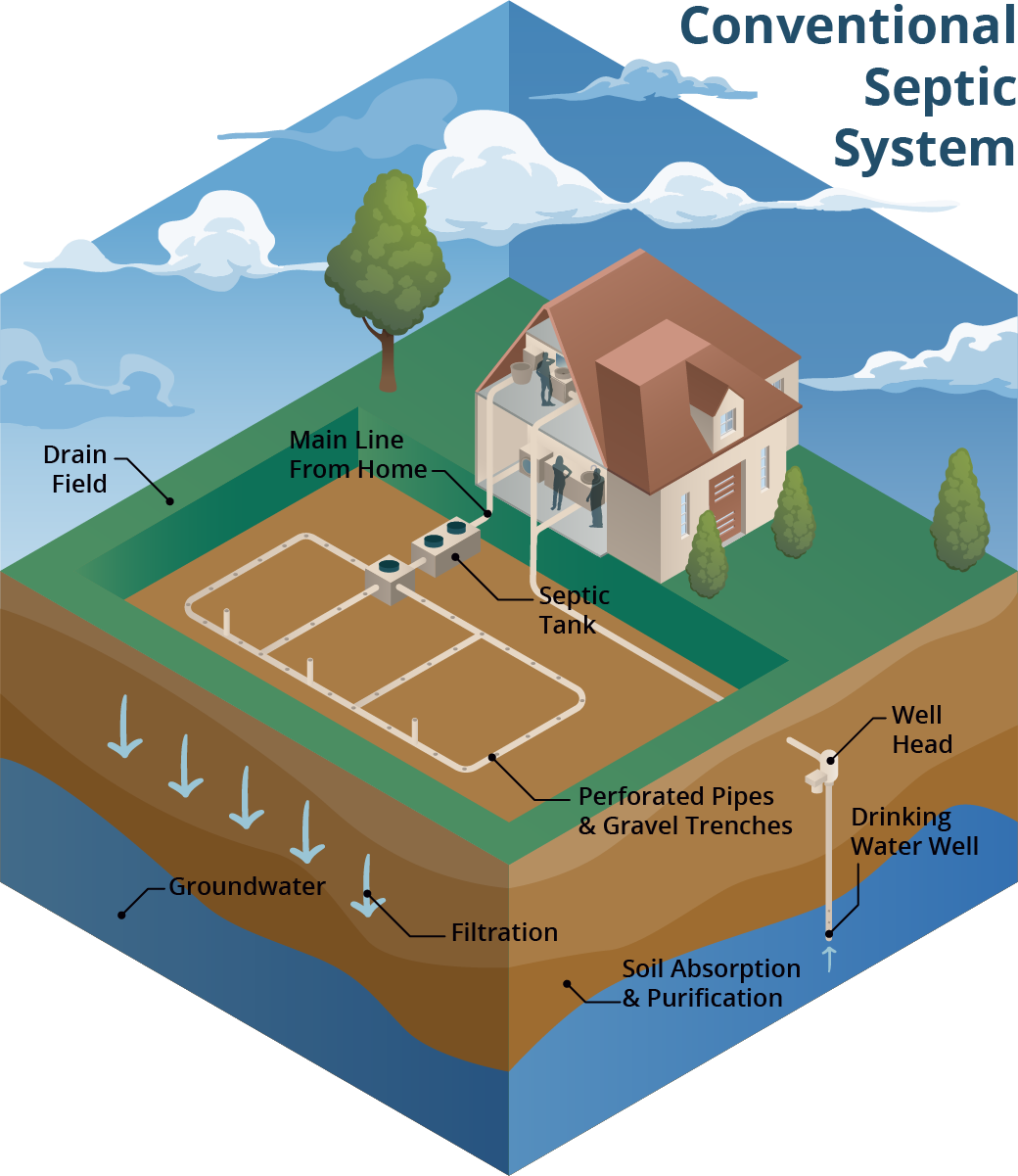

A conventional septic system is made up of a septic tank (a watertight container buried in the gound) and a drainfield. Image: Soil and Water Science Lab UF/IFAS GREC.

A conventional septic system is made up of a septic tank and a drainfield or leach field. Wastewater flows from the septic tank into the drainfield, which is typically made up of a distribution box (to ensure the wastewater is distributed evenly) and a series of trenches or a single bed with perforated PVC pipes. Wastewater seeps from these pipes into the surrounding soil. Most wastewater treatment occurs in the drainfield soil. When working properly, many contaminants, like harmful bacteria, are removed through die-off, filtering and interaction with soil surfaces.

What should you do if flooding occurs?

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) offers these guidelines:

- Relieve pressure on the septic system by using it less or not at all until floodwaters recede and the soil has drained. Under flooded conditions, wastewater can’t drain in the drainfield and can back up in your septic system and household drains. Clean up floodwater in the house without dumping it into the sinks or toilet. This adds additional water that an already saturated drainfield won’t be able to process. Remember that in most homes all water sent down the pipes goes into the septic system.

- Avoid digging around the septic tank and drainfield while the soil is waterlogged. Don’t drive vehicles or equipment over the drainfield. Saturated soil is very susceptible to compaction. By working on your septic system while the soil is still wet, you can compact the soil in your drainfield, and water won’t be able to drain properly. This reduces the drainfield’s ability to treat wastewater and leads to system failure.

- Don’t open or pump the septic tank if the soil is waterlogged. Silt and mud can get into the tank if it is opened and can end up in the drainfield, reducing its drainage capability. Pumping under these conditions can cause a tank to float or ‘pop out’ of the ground, and can damage inlet and outlet pipes.

- If you suspect your system has been damaged, have the tank inspected and serviced by a professional. How can you tell if your system is damaged? Signs include: settling, wastewater backs up into household drains, the soil in the drainfield remains soggy and never fully drains, a foul odor persists around the tank and drainfield.

- Keep rainwater drainage systems away from the septic drainfield. As a preventive measure, make sure that water from roof gutters doesn’t drain towards or into your septic drainfield. This adds an additional source of water that the drainfield has to process.

- Have your private well water tested if your septic system or well were flooded or damaged in any way. Your well water may not be safe to drink or use for household purposes (making ice, cooking, brushing teeth or bathing). You need to have it tested by the Health Department or other certified laboratory for total coliform bacteria and coli to ensure it is safe to use.

For more information on septic system maintenance after flooding, go to:

More information on having your well water tested can be found at:

More Information on conventional and advanced treatment septic systems can be found on the UF/IFAS Septic System website