by Rick O'Connor | Jun 18, 2021

In our continuing series on the biogeographic distribution of island vertebrates, this week we look at a creature that, for some, is as scary as sharks – the rays. The term stingray conjures up stinging barbs and painful encounters, and these have happened, but rays are easily scared away by our activity. Occasionally people will step on one and the venomous spine is used to make you move your foot. You can avoid this by shuffling your feet when moving across the sand. Rays detect the pressure and move before you reach them. Again, negative encounters with rays are not common.

The Atlantic Stingray is one of the common members of the ray group who does possess a venomous spine.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

There are 18 species of rays (from 9 families) found in our area. An interesting note, only eight of those possess a barb for stinging, and five are from the family Dasyatidae (the stingrays). Others that have barbs include the butterfly ray, cownose ray, and the eagle ray.

Rays are related to sharks but differ in that (a) the pectoral fin begins before the gills slits, and (b) the gill slits are on the underneath of the body – not on the side as found in sharks. Shark distribution seems to be controlled by water temperature. We see this with ray distribution as well, but interestingly the skates seem to be restricted to the Gulf of Mexico. Some are found almost exclusively in the east or west side of the Gulf.

Skates resemble stingrays but lack the venomous barb. They will usually have small thorns on their bodies and lay their developing embryos in a leathery egg case folks call “mermaid’s purse” when they wash ashore. There are four species found in the Gulf, but the spreadfin skate is ONLY found in the Gulf of Mexico and is not found along the Florida peninsula. The clearnose skate, which can be found all along Florida and the eastern seaboard of the U.S., is absent from western Gulf. It is interesting to try and understand why. What barrier keeps these two skates from colonizing the entire Gulf?

There is a large plume of muddy freshwater that expands from the Mississippi River into the Gulf off Louisiana. This plume could be a barrier for coastal species trying to expand their range. However, the spreadfin skate is reported to be an outer continental shelf species and may not be influenced by this lower salinity water. So, what is their story?

And why are these not found in the Caribbean? In the Caribbean you do enter tropical waters where coral reefs become more common. There is certainly a species shift when you reach this zone and it could be the food needed by these skates is not found here – a biological barrier. Many find these biogeographic situations interesting.

There are 12 species that have the typical “Carolina marine fish” distribution, which means they are found throughout the Gulf up the eastern seaboard to Massachusetts and south to Brazil. Two, the Atlantic torpedo ray and the roughtail stingray, expand their range farther into Canada. As a matter of fact, the roughtail stingray prefers colder waters.

Torpedo rays are an interesting group. This family of fish includes two species here in the Gulf, the Atlantic torpedo ray and the lesser electric ray. Yep… these two have special muscle cells that can deliver an electric shock. It is believed this electric current can detect and stun prey as well as repel predators. The voltage is not dangerous but will get your attention.

Three of those “Carolina marine species,” the guitarfish, the lesser electric ray, and the yellow stingray, do not reach Massachusetts. Their distribution ends at North Carolina. You would have to guess water temperature as a barrier here. The warm Gulf stream begins heading east across the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Hatteras towards Europe. They could follow this current to Bermuda, but they have not been reported there. This could be due to depth (pressure), being benthic fish, or food barriers.

There is one family that is tropical, the sawfish. These bizarre dinosaur looking creatures were once common in the estuaries of the Gulf region. They are now rare and protected.

One species of stingray, the Atlantic stingray has been found in the lower reaches of Louisiana rivers. Like bull sharks, salinity may not be a barrier for them.

And then we have our “world travelers”. The manta and eagle rays are found across the globe in tropical waters, and eagle rays are common in temperate parts of the world.

The distribution of our rays is not as universal as sharks. The skates in particular have an interesting distribution pattern. Pensacola lies right at the boundary of the eastern and western Gulf of Mexico, so we find both geographic groups here. Though they may scare many people, rays are fascinating creatures and cool to see.

by Erik Lovestrand | Jun 3, 2021

Identifying North Florida river turtles can be quite challenging, given the fact that several species are collectively referred to as “streak-ed heads” by many people. Although you will not find this term in the scientific naming conventions, it is actually an apt description for many turtles in the Southeast that have dark skin with thin, yellow pinstripes on their head and neck. North Florida has at least half a dozen species that fall into this general grouping. They include the Suwannee cooter, river cooter, Florida cooter, chicken turtle, yellow-bellied slider and a couple of map turtles. We even have a disjunct population of Florida red-bellied turtles on the Apalachicola River that are isolated from the main group, which is restricted to peninsular Florida and extreme Southeastern Georgia. Overall, we have about 25 species of turtles in Florida.

Suwannee cooters at Lafayette Blue Springs, Lafayette County, Florida, 2021.

FWC Photo by Andy Wraithmell

As you might guess, the key to accurate river turtle identification lies in the details and the details can be tough to see. Most basking turtles tend to tumble off their logs into the water long before you are close enough to scrutinize their features. However, a few tips and tricks may improve your chances when going afield. A good pair of binoculars and a reptile field guide are must-haves. You need to be able to see if the yellow on the side of the head is a wide splash (as on the yellow-bellied slider), or a series of thin lines (as on various cooters). If the top shell (carapace) is very dark and the bottom shell (plastron) shows orange color, you might have a red-belly or Suwannee cooter (higher dome on red-belly, relatively). Two of our native species have what are referred to as “striped breeches”. When viewed from the rear, the stripes on the hind legs are vertically oriented on the yellow-bellied slider and the Florida chicken turtle. The chicken turtle is distinguished by a relatively narrower head and a wide, yellow stripe on the front legs. Separating the various cooter species gets a little trickier. You need to use characteristics like the pattern on the plastron, the occurrence of “hairpin-shaped” stripes on the head, or the pattern of lines on particular carapace scutes.

So how do you get those clues in the wild? A good telephoto lens may work if you are fortunate enough to own one. This will give you the opportunity to study detailed features at your leisure. Otherwise, you may not be able to identify a turtle to the species level. Getting close to a wary turtle is not easy. However, on busy stretches of our waterways, where wildlife are desensitized to people and boats, turtles generally have a wider comfort zone. Especially if you are in a canoe or kayak and minimize your movement and sound as you glide in for a better view. Lastly, go looking on a bright sunny day and your opportunities will vastly increase as turtles climb out of the water onto logs to soak up some of that good old Florida sunshine. One species that you should have no trouble naming when encountered, is the softshell turtle. Softshells will extend their extremely long neck upward when basking and their flexible, smooth shell will appear flattened in profile. They are the only turtles here with a tubular snout. Never try to pick one up if encountered crossing a road, as they do not hesitate to bite and have extremely sharp and powerful jaws. In general, even if you are confident in not getting nailed, you will probably be wrong, given the extremely long neck that can reach more than halfway back on the shell. Also, all of our water turtles have very sharp claws on their hind feet and will manage to get in a few good rakes before you decide to put them down, or worse yet, drop them on the pavement and injure them.

Now, when you think you are getting good at basking turtle identification, start looking for some of our less obvious, smaller species. These include stinkpots, musk turtles, mud turtles, map turtles and box turtles; all very cool critters. But if you think you want to pick up one of the cute little buggers, beware. Most of the little ones will bite too…hard! Believe me. Happy “turtling!”

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 3, 2021

With this article we are going to begin a short series on the biogeography of panhandle vertebrates. Biogeography is the study of distribution of life and why species are found where they are. Many are interested in what species are found in a specific location, such as which sharks are found in our area, but understanding why others are not is as interesting.

The Bull Shark is considered one of the more dangerous sharks in the Gulf. This fish can enter freshwater but rarely swims far upstream. Photo: Florida Sea Grant

All species have a point of origin and from there they disperse across the landscape, or ocean, until they reach a barrier that stops that dispersal. These barriers can be something physical, like a mountain range, something climatic, like the average temperature, or something biological, like to abundance of a specific food or predator. There are a lot of barriers that impede dispersal and explain why some species are not present in some locations.

Sharks are marine fish. In general, there is little to impede the dispersal of marine fish. All oceans are connected and there is no reason why a shark found in the Gulf of Mexico could not swim to Australia, and some have. But there are barriers that keep some species of south Florida fish from reaching north Florida – mean water temperature being one.

There are 24 species of sharks from nine different families found in the Gulf of Mexico. Most have a wide distribution range, and some are found worldwide. Nurse sharks are more tropical, common in the Keys, but are found in our area of the northern Gulf of Mexico. They are fans of structure and are often found near our artificial reefs.

Whale sharks and hammerheads are circumtropical, meaning they are restricted by water temperature but found worldwide in warmer waters. Whale sharks are the largest of all fish, reaching a mean length of 45 feet, and are not common near shore. They are plankton feeders and, though large, are harmless to humans. There are five species of hammerheads found in the Gulf of Mexico. They are easily identified by their “hammer” shaped head and are known for their large dorsal fin that, at times, will extend above the surface while they are swimming. Finding species of hammerhead inside the bay is not uncommon.

Several of our local sharks are not as restricted by water temperature and are found as far north as Canada. Sand tigers, threshers, and dogfish seem to prefer the cooler waters and, though found in the Gulf, are not common. There are two members of the mackerel shark family found here. Great whites, of movie fame, prefer cooler waters and are found worldwide – except for polar waters. There are records in the Gulf, but most are offshore in cooler waters. As you know, these are large predatory sharks, reaching up to 25 feet in length, and are known to feed on large prey such as seals. Their cousin the shortfin mako, prefers warmer waters and is more common here. Nearshore encounters with makos is rare but has happened.

The largest family, and best known, are the requiem sharks. There are 13 species in the Gulf, and many are common in our area. Many are not as restricted by water temperature and can be found as far north as New York. Bull sharks are not restricted by salinity and have been found up rivers in Alabama, and Louisiana. Silky sharks are more tropical, and the tiger and spinner sharks are more circumtropical.

The geographic distribution of sharks seems centered on water temperature. Most can easily swim the oceans to locations across the globe but congregate in areas of preferred temperatures and food. Though feared because of attacks on humans, a rare thing actually, they are fascinating animals and world travelers.

by Rick O'Connor | May 20, 2021

I was recently gathering information together for a presentation on Florida snakes, highlighting those in the Florida panhandle. This particular reference listed 44 species found in the state. Of those, 29 were found throughout the state – north, central, and south Florida. Granted, there were subspecies for many which made for some distinction, but most of our snakes (66%) have few barriers and seem to have adapted to the different habitats and climates. And let’s face it, north and south Florida are two different worlds. That says a lot for the adaptability of these animals, they are pretty amazing.

Snakes do make many nervous but most of our 44 species are nonvenomous.

Photo: Nick Baldwin

Another trend was obvious. As you looked at those species which were only found in north Florida (here defined as the panhandle across to Jacksonville and south to Gainesville) and compared that to species only found south of Gainesville, we have a rich diversity of snakes in our part of the state. There were 12 species found in Florida that were only found in north Florida. South and central Florida only had 3 species that were unique to their part of the state. I saw this same trend with turtles. Of the 25 species of turtles found in Florida, 9 are unique to north Florida, 2 to central and south.

It has been known that the biodiversity of the panhandle is pretty amazing, and that the Apalachicola River basin in particular is a biodiversity hot spot. In the panhandle, several “worlds” collide and species, many using these river systems we find here, can easily reach this area. Some produce hybrid versions of two species. Some produce new species only found here. There may be more reptiles / acre in central and south Florida (I did not look at that) but the variety of these creatures in the north Florida is pretty amazing.

The Escambia River. One of the alluvial rivers of the Florida panhandle. Is a natural highway for many reptiles to disperse into our state.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

But what about those 12 species unique to our part of the state?

Four of them are small terrestrial snakes, rarely getting over a foot in length. These are easy prey and nonvenomous so are most often found beneath the leaf litter of the forest, or beneath the ground, coming out at night to feed on small creatures. We generally find them living in our flower beds and gardens. Most are ovoviviparous (producing an egg but instead of laying it in a nest, the female keeps it internally giving live birth), with only the Southeastern Crowned Snake laying eggs (oviparous).

- Smooth Earth Snake (Virginia valeria) This snake has records from Pensacola Bay area and areas south of the Georgia line.

- Rough Earth Snake (Virginia striatula) This snake has most records west of the Apalachicola River, but there are records from the Suwannee basin in north Florida.

- Red-bellied Snake (Storeia occipitomaculata) Common across north Florida.

- Southeastern Crowned Snake (Tantilla coronate) Found only in the panhandle.

Six of the unique panhandle 12 are nonvenomous water snakes. This would make sense in that we are host to several long alluvial rivers that reach deep into the southeast. The Escambia, Choctawhatchee, and Apalachicola Rivers are highways for all sorts of riverine species, and those closely associated with rivers, to cover hundreds of miles of territory with few barriers (except for the occasional dam). Though these water snakes are nonvenomous, they are known for the “bad attitudes” and high tendency to bite. They feed on a variety of prey and are often seen basking along the riverbank or in a tree branch hanging over the water where they can escape quickly if trouble comes, and they do escape quickly. Some are quite large (over 4 feet) and most are ovoviviparous. The northern watersnake is known to have a placenta-like structure to nourish its young (viviparous) and the rainbow snake lays eggs (oviparous).

The banded watersnake is one found throughout the state and resembles the cottonmouth.

Photo: UF IFAS

- Queen Snake (Regina septemvittata) is only found in the western panhandle (west of the Apalachicola River). This snake likes cold, clear streams with rocky or sandy bottoms and plenty of crayfish.

- Northern Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon) also is only found in the western panhandle. It can be found in almost any body of water and has been reported on barrier islands.

- Plain-bellied Snake (Nerodia erythrogaster) This snake also can be found in just about any water system.

- Diamondback Watersnake (Neroida rhombifer) has only been found in the Pensacola Bay area (Escambia and Santa Rosa counties). They can be found at times in large numbers around almost any body of water.

- Western Green Watersnake (Neroida cyclopion) only as records in one Florida county – Escambia. There they have been found in a variety of water habitats including man-made ones.

- Rainbow Snake (Farancia erytogramma) This snake likes to feed on American eels and is usually found in aquatic systems where this prey inhabits.

Another interesting trend with these unique panhandle watersnakes is the number only found in the western panhandle. Four of the six are only found there and two are only found in the Pensacola area. Some say, “Pensacola is not really Florida”, the snakes might agree.

The last two of the unique 12 are venomous snakes. Florida has six species of venomous snakes, but two are only found in the north Florida.

This copperhead was found JUST across the state line in Alabama. The more copper color and “hour-glass” pattern of their bands lets you know it is not it’s cousin the cottonmouth.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

- Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix). Though quite common in Alabama and Georgia, most records in our state are from the Apalachicola River basin area. Many local panhandlers will tell you they see this snake everywhere, but they use this name for the cottonmouth also (a close cousin). The true copperhead is not common here. It seems to like rocky areas further north and is usually found with limestone rock areas that have been formed over time from river erosion.

- Timber Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus). As with the copperhead, this is a common snake in Alabama and Georgia associated with rocky terrain and is not common in our state. Many ole timers will speak of the “canebrake”, which was found in the common cane of north Florida. There was discussion at one point of this being a separate species from the timber rattler, but the specialist now believe they are one in the same. So, the name canebrake is no longer used by herpetologists. Records of this snake in Florida are mostly east of the Apalachicola River and not common.

This timber rattlesnake has chevrons (stripes) instead of the diamond pattern on its back.

Photo provided by Mickey Quigley

I think the diversity of wildlife in our part of the state is pretty special. Even if you do not like snakes, it is pretty neat that we have so many kinds not found south of the Suwannee River. Snake watching is not as popular as bird watching, for obvious reasons, but it is still neat that we have these guys here.

by Andrea Albertin | Jan 28, 2021

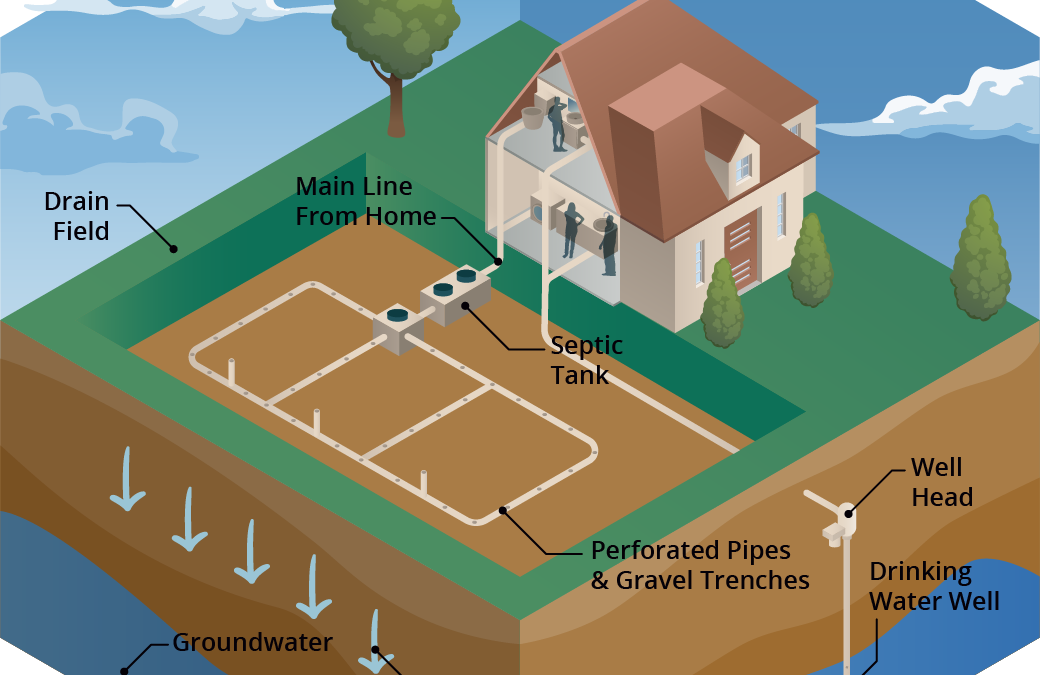

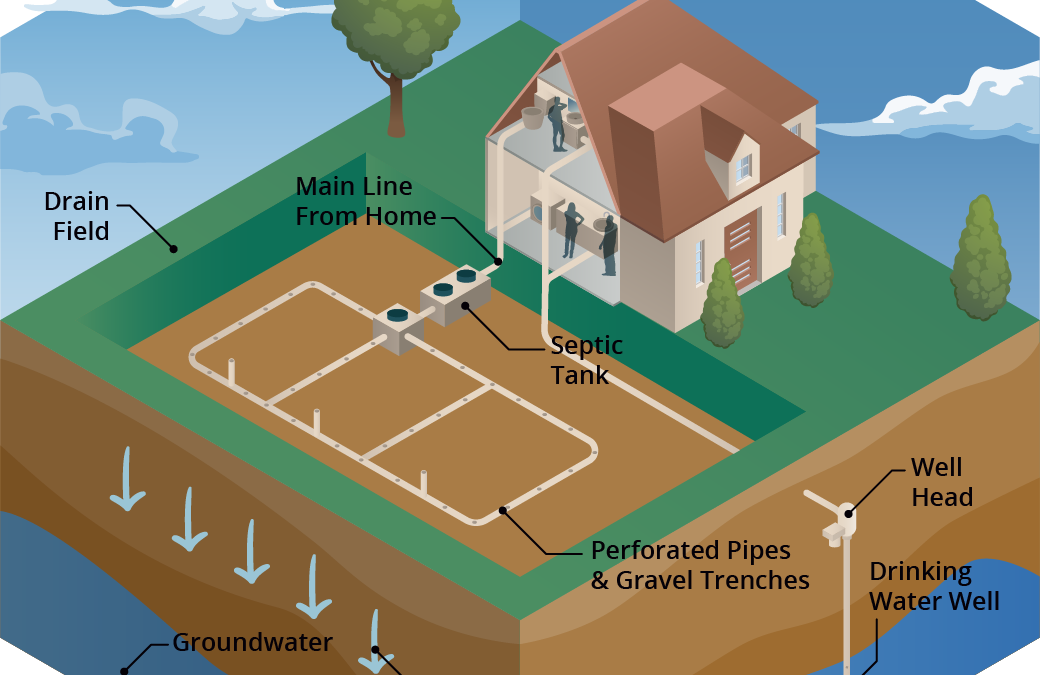

Senate Bill 712 ‘The Clean Waterways Act’ was signed into Florida law on June 30, 2020. The purpose of the bill is to better protect Florida’s water resources and focuses on minimizing the impact of known sources of nutrient pollution. These sources include septic systems, wastewater treatment plants, stormwater runoff as well as fertilizer used in agricultural production.

Senate Bill 712 focuses on protecting Florida’s water resources such as Jackson Blue Springs/Merritt’s Mill Pond, pictured here. Credit: Doug Mayo, UF/IFAS.

What major provisions are included in SB 712?

Primary actions required by SB712 were listed in a news release by Governor Desantis’ staff in June 2020 as:

- Regulation of septic systems as a source of nutrients and transfer of oversight from the Florida Department of Health (DOH) to the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (DEP).

- Contingency plans for power outages to minimize discharges of untreated wastewater for all sewage disposal facilities.

- Provision of financial records from all sanitary sewage disposal facilities so that DEP can ensure funds are being allocated to infrastructure upgrades, repairs, and maintenance that prevent systems from falling into states of disrepair.

- Detailed documentation of fertilizer use by agricultural operations to ensure compliance with Best Management Practices (BMPs) and aid in evaluation of their effectiveness.

- Updated stormwater rules and design criteria to improve the performance of stormwater systems statewide to specifically address nutrients.

How does the bill impact septic system regulation?

The transfer of the Onsite Sewage Program (OSP) (commonly known as the septic system program) from DOH to DEP becomes effective on July 1, 2021. So far, DOH and DEP submitted a report to the Governor and Legislature at the end of 2020 with recommendations on how this transfer should take place. They recommend that county DOH employees working in the OSP continue implementing the program as DOH-employees, but that the onsite sewage program office in the State Health Office transfer to DEP and continue working from there. DOH created an OSP Transfer web page where updates and documents related to the transfer are posted.

How does the bill impact agricultural operations?

SB 712 affects all landowners and producers enrolled in the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (FDACS) BMP Program. Under this bill:

- Every two years FDACS will make an onsite implementation verification (IV) visit to land enrolled in the BMP program to ensure that BMPs are properly implemented. These visits will be coordinated between the producer and field staff from FDACS Office of Agriculture and Water Policy (OAWP).

- During these visits (and as they have done in the past), field staff will review records that producers are required to keep under the BMP program.

- Field staff will also collect information on nitrogen and phosphorus application. FDACS has created a specific form, the Nutrient Application Record Keeping Form or NARF where producers will record quantities of N and P applied. FDACS field staff will retain a copy of the NARF during the IV visit.

FDACS-OAWP prepared a thorough document with responses to SB 712 Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ’s). It includes responses to questions about site visits, the NARF and record keeping, why FDACS is collecting nutrient records and what will be done with this information. The fertilizer records collected are not public information, and are protected under the public records exemption (Section 403.067 Florida Statutes). For areas that fall under a Basin Management Action Plan (like the Jackson Blue and Wakulla Springs Basins in the Florida Panhandle), FDACS will combine the nitrogen and phosphorus application data from all enrolled properties (total pounds of N and P applied within the BMAP). It will then send the aggregated nutrient application information to FDEP.

Details of how all aspects of SB 712 will be implemented are still being worked out and we should continue to hear more in the coming months.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 8, 2021

It’s winter…

The sky is clear, the humidity is low, the bugs are gone, and the highs are in the 60s – most days. These are perfect days to get outside and enjoy. But the water is cold and you do not want to get wet – most days. And with COVID hanging around we do not want to go where there are crowds. Where can I go to enjoy this great weather, the outdoors, but stay safe?

As the summer heat fades, the weather is great for hiking! Photo credit: Abbie Seales

Hiking…

My wife and I have already made several hikes this winter and have enjoyed each one. Each panhandle county has several hiking trails you could visit. In our county there are city, county, state, and federal trails to choose from. The Florida Trail begins in Escambia County, at Ft. Pickens on Santa Rosa Island, and dissects each county in the panhandle on its way to the Everglades. You could find the section running through yours and hike that for a day. Community parks, our local university, state and national parks, and the water management district, all have trails.

Some are a short loops and easy. Others can be 20 plus miles, but you do not have to hike it all. Go for as long as you like and then return to the car. Some are handicapped access, some have paved sections, or boardwalks. Some go along waterways and the water is so clear in the winter that you can see to the bottom. Many meander through both open areas and areas with a closed tree canopies.

The tracks of the very common armadillo.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

The boardwalk of Deer Lake State Park off of Highway 30-A. you can see the tracks of several types of mammals who pass under at night.

Being winter, the wildlife viewing may be less. The “warm bloods” are moving – birds and mammals. Actually, the birds are everywhere, it is a great time to go birding if you like that. Mammals are still more active at dawn dusk, but their tracks are everywhere. We have seen raccoon, coyote, and deer on many of our hikes. But the insects are down as well. We have not had a yellow fly or mosquito gives us a problem yet. Some fear snakes, we actually like the see them, but we have not. Many will come out of their dens when the days warm and the sun is out to bask for a bit before retreating back into their lair. You might feel more comfortable hiking knowing the chance of an encounter one this time of year is much less.

One of the many Florida State Forest trails in South Walton.

The Florida Trail extends (in sections) over 1,300 miles from Ft. Pickens to the Florida Everglades. It begins at this point.

But the views are great and the photography excellent. Some mornings we have had fog issues, but it quickly lifts, and the bay is often slick as glass with pelicans, loons, and cormorants paddling around. These have made for some great photos.

Things to consider for your hike.

Good shoes. Many of the trails we have hiked have had wet and muddy sections.

Temperature. There can be big swings when going from open sunny areas to under the tree canopies. Wear clothes in layers and have a backpack that can hold what you want to take off. Some like to wear the fleece vests so they do not have to put on/remove as they hike.

Water. I bring at least 32 ounces. It is not hot, but water is still needed.

Snacks. Always a plus. I always miss them when I do not have them.

Camera. Again, the scenery and the birds are really good right now.

The best thing is that you are getting outside, getting exercise, and getting away from the crazy world that is going on right now. Take a “mind break” and take a hike.

Here are some hikes suggested by hiking guides.

Gulf Islands National Seashore / Ft. Pickens – Florida Trail (Ft. Pickens section) – 2 miles – Pensacola Beach

Blackwater State Forest – Jackson Red Ground Trail – 21 miles – near Munson FL

Falling Waters State Park – Falls, Sinkhole, and Wiregrass Trail – ~ 1 mile – near Chipley on I-10

Grayton Beach State Park – Dune Forest Trail – < 1 mile – 30-A in Walton County

T.H. Stone Memorial St. Joseph Peninsula State Park – Beach Walk and Wilderness Preserve Trail – ~ 9 miles – near Port St. Joe FL

Apalachicola Bluffs and Ravine Preserve – Garden of Eden Trail – 4 mile loop – Hwy 12 near Bristol FL

Torreya State Park – Torreya River Bluff Loop Trail – 7 mile loop – Hwy 271 near Bristol

Leon Sinks Geological Area – Sinkhole and Gumswamp Trail – 3 mile loop – US 319 near Tallahassee

Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park – Sally Ward Springs and Hammock Trails – 2.5 miles out and back – Hwy 20 near Wakulla FL

St. Marks National Wildlife Refuge – Stoney Bayou Trail – ~ 6 miles – CR 59 near Gulf of Mexico