by Sheila Dunning | Dec 13, 2019

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.

Some North American breeding birds endure harsh winters; however, they are physically suited for cold environments in a number of ways. One, they are able to drop their metabolic rate to a near comatose state using very little energy. Two, they are able to position their feathers, or puff up, to trap heat generated by their own body. Others need to head to warmer climates.

Birds migrate for two reasons. Food and weather avoidance. North American breeding birds who nest in the northern part of the continent will migrate south for the winter. As winter approaches, insect and plant life diminishes in the snow-covered states. Migrating birds head south in search of food. Places like Florida are rich in insects, plant life, and nesting grounds.

Birds need high energy food to stay warm. Berry and seed producing plants contain proteins, sugars and lots of fats. Many native trees, shrubs and grasses can aid migratory and winter visiting birds in their relentless search for food. Gardening for birds and other wildlife enables an opportunity for people to experience animals up close, which providing an important habitat in the urban environment.

For more information on which plants are preferred by specific bird species go to: https://www.audubon.org/native-plants

For more information on landscaping for wildlife refer to: https://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/pdffiles/UW/UW17500.pdf

by Shep Eubanks | Nov 14, 2019

Eastern Wild Turkey Gobbler in Gadsden County – photo by Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

The above picture of a strutting Eastern Wild Turkey is a sight that many hunters look forward to seeing every spring here in the panhandle of Florida. In order to manage wild turkeys and their habitat it is good to understand some basic facts about their biology.

Wild turkeys are considered a generalist species, meaning that they can eat a wide variety of foods, primarily seeds, insects, and vegetation. They prefer relatively open ground cover so that they can see well and easily move through their surroundings, but they aren’t picky about where they live as long as it provides them year-round groceries and safety. They are also a very adaptable species. Turkeys prefer low, moderately open herbaceous vegetation (less than three feet in height) that they can see through, or see over, and through which they can easily move in relatively close proximity to forested cover. Such open habitat conditions help them see and avoid predators and these areas will typically provide sufficient food in terms of edible plants, fruit, seeds, and insects.

Wild turkeys are considered, ecologically, to be a “prey species” and have evolved as a common food source for numerous animals—seems everything is trying to eat them. Turkey eggs, young (i.e.,poults), and adults are preyed on by such animals as bobcats, raccoons, skunks, opossum, fox , coyotes, armadillos, crows, owls, hawks, bald eagles, and a variety of snakes. Being prey to so many different animals has shaped the turkey’s biology and behavior. Turkeys experience high mortality rates and don’t live very long, on average, <2 years. They are particularly vulnerable during nesting and immediately after hatching. Because of this high mortality, reproduction is really important for turkey populations to replace the individuals that don’t survive from year to year. Wild turkeys have adapted to being a prey species in part, though, by having a high reproductive potential. Hens have the capacity to lay large clutches of eggs. If a nest is destroyed or disturbed, especially during the egg laying or early incubation period, the hen will often re-nest. Turkeys are also polygamous, with males capable of breeding multiple females, which further boosts their reproductive potential.

Turkey hen with poults foraging in a grassy field in Gadsden County – photo by Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

Newly hatched turkeys, referred to as poults, need grassy, open areas so they can find an abundance of insects. Such areas are usually the most critical, and often the most lacking habitat in Florida. Under ideal conditions for turkeys, grassy openings would occupy approximately 25 percent of a turkey’s home range. Additionally, it is of equal importance to have such openings scattered throughout an area, varying in size from 1 to 20 acres such that they are small, or irregular in shape, to maximize the amount of adjacent escape cover (moderately dense vegetation or forested areas that can provide concealment from predators or other disturbances). Large, expansive openings (e.g., large pastures) without any escape cover are not as useful for turkeys since they generally will not venture more than 100 yards away from suitable cover.

Good habitat allows turkeys to SEE approaching danger and to MOVE unimpeded (either to move away from danger or simply to move freely while foraging without risk of ambush). In other words, good habitat provides the right vegetative structure. When thinking about habitat for turkeys, it’s good to always think from a turkey’s point of view….about 3 feet off the ground! Turkeys like open areas where they can see well and easily move.

Burning pine land in Gadsden County to improve wild turkey habitat – photo by Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

One of the best management techniques to manage vegetation structure and composition is prescribed fire. Fire can be very destructive, but if properly applied, fire can be quite beneficial to wildlife and is one of the best things you can do for wild turkeys. When applied correctly, fire has many benefits. Some of the benefits of fire to turkeys and other wildlife include: control of hardwood by setting back woody shrubs and trees in the under story; improving vegetation height and structure; stimulating new herbaceous growth at ground level; stimulating flowering and increased fruit production in some plants; it improves nutritional value and increases palatability of vegetation. All of this leads to increased insect abundance and fewer parasites in the environment. Prescribed fire also has benefits for the landowner. Applied properly and regularly, prescribed fire will reduce risk of catastrophic wildfire which can destroy a timber stand. It reduces hardwood competition so favored pines grow faster and healthier; and reduces the risk of disease, particularly after a thinning or timber cut, by removing logging debris that would otherwise attract insects and disease-causing agents. It can also help control invasive species, and best of all it’s the least expensive option on a cost per acre basis.

Gobblers in pine stand after burn – Game Camera photo by Shep Eubanks

Another good practice is simply mowing or bush-hogging. Even in areas that aren’t super thick (such as around forest and field edges, or seasonal wetlands), mowing and bush-hogging alone, even without fire, are beneficial as they have much the same effect on the habitat as fire. Basically, you’re removing grown up vegetation and allowing light to reach the ground again. Within pine plantations, roads often provide some of the best, or only, turkey habitat simply because the surrounding vegetation becomes too dense so roads are used for feeding and moving throughout the area. In this regard, wide roads increase the amount of open habitat which provides lots of insects, seeds, and edible vegetation. They also reduce the opportunity for predators to ambush turkeys which can readily occur on narrow roads. Having wide roads is a good land management practice that lets roads dry-out quicker so that they can hold up to traffic better.

If you have pine dominated timber stands on your property, proper thinning is not only good for turkeys, but it’s good for your stand. Young pine stands, particularly those in sapling or early pole stages, are often too thick for wild turkeys, except as escape cover. They get so dense that they shade out everything underneath. They may produce some pine seeds when they get older, but for most of the year, there’s nothing to eat and nothing to attract turkeys to the area. For turkeys, thinning opens up the canopy and allows sunlight to reach the forest floor, which in turn stimulates plant growth of grasses, forbs and soft-mast producing shrubs.

If you have an interest in turkeys, do most management activities outside of the nesting season, which generally runs from the middle of March through June. From a practical standpoint that is not always possible, so on the positive side, if a nest is destroyed (whether by predators or management efforts), a hen will quite often re-nest. Also, the overall importance of management will often outweigh the loss of 1 or 2 nests. The time that turkey nests are at a premium is when a turkey population is low or just trying to get established into an area. In such cases every nest is valuable.

For more information consult with your local Extension Agent .

by Sheila Dunning | Oct 10, 2019

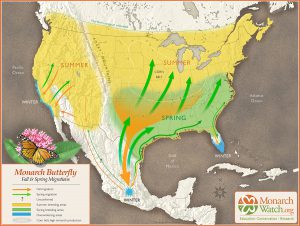

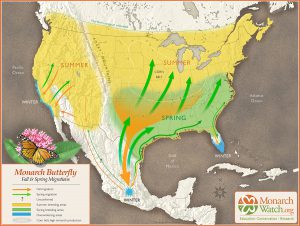

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

Over 1.8 million Monarch butterflies have been tagged and tracked over the past 27 years. This October these iconic beauties will flutter through the Florida Panhandle on their way to the Oyamel fir forests on 12 mountaintops in central Mexico. Monarch Watch volunteers and citizen scientists will be waiting to record, tag and release the butterflies in hopes of learning more about their migration and what the 2019 population count will be.

This spring, scientists from World Wildlife Fund Mexico estimated the population size of the overwintering Monarchs to be 6.05 hectacres of trees covered in orange. As the weather warmed, the butterflies headed north towards Canada (about three weeks early). It’s an impressive 2,000 mile adventure for an animal weighing less than 1 gram. Those butterflies west of the Rocky Mountains headed up California; while the eastern insects traveled over the “corn belt” and into New England. When August brought cooler days, all the Monarchs headed back south.

What the 2018 Monarch Watch data revealed was alarming. The returning eastern Monarch butterfly population had increased by 144 percent, the highest count since 2006. But, the count still represented a decline of  90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

90% from historic levels of the 1990’s. Additionally, the western population plummeted to a record low of 30,000, down from 1.2 million two decades ago. With estimated populations around 42 million, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service began the process of deciding whether to list the Monarch butterfly as endangered or threatened in 2014. With the additional information, FWS set a deadline of June 2019 to decide whether to pursue the listing.

Scientists estimate that 6 hectacres is the threshold to be out of the immediate danger of migratory collapse. To put things in scale: A single winter storm in January 2002 killed an estimated 500 million Monarchs in their Mexico home. However, with recent changes on the status of the Endangered Species Act, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has delayed its decision until December 2020. One more year of data may be helpful to monarch conservation efforts.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

Individuals can help with the monitoring and restoring the Monarch butterflies habitat. There are two scheduled tagging events in Panhandle, possibly more. St. Mark’s National Wildlife Refuge is holding their Butterfly Festival on Saturday, October 26 from 10a.m. to 4 p.m. Henderson Beach State Park in Destin will have 200 butterflies to tag and release on Saturday, November from 9 – 11 a.m. Ask around in the local area. There may be more opportunities.

There is something more you can do to increase the success of the butterflies along their migratory path – plant more Milkweed (Asclepias spp.). It’s the only plant the Monarch caterpillar will eat. When they leave their hibernation in Mexico around February or March, the adults must find Milkweed all along the path to Canada in order to lay their eggs. Butterflies only live two to six weeks. They must mate and lay eggs along the way in order for the population to continue its flight. Each generation must have Milkweed about every 700 miles. Check with the local nurseries for plants. Though orange is the most common native species, Milkweed comes in many colors and leaf shapes.

by hollyober | Oct 10, 2019

Insect pests can destroy substantial quantities of crops, prompting growers to invest heavily in pesticide use. Previ

These three common species of bats in FL, GA, and AL eat insect pests notorious for causing substantial damage to crops: the Seminole bat (Lasiurus seminolus), southeastern bat (Myotis austroriparius), and evening bat (Nycticeius humeralis) (photo credits @MerlinTuttle.org).

ous research in Texas suggested that bats could reduce pesticide costs by over a million dollars within their state, due to the bats’ fondness for pests that damage cotton. Scientists at UF/IFAS recently collected evidence locally that indicates bats are providing valuable assistance with pest reduction for many of the crops grown here too.

During spring and summer of 2018 scientists at UF clarified what the common species of bats were eating in north Florida, south Georgia, and south Alabama. We investigated 161 bats across 21 counties and found that 28% of these bats ate at least one Lepidopteran (moth) pest species, 21% ate a Coleopteran (beetle) pest, and 18% ate a Hemipteran (true bug) pest. In total, 12 different species of agricultural pest species were eaten by these bats.

The moth pests consumed by bats were:

- Green Cutworm Moth (Anicla infecta)

- Tobacco Budworm (Chloridea virescens)

- Soybean Looper (Chrysodeixis includens)

- Garden Tortrix (Clepsis peritana)

- Lesser Cornstalk Borer (Elasmopalpus lignosellus)

- Corn Earworm (Helicoverpa zea)

- Beet Armyworm (Spodoptera exigua)

- Fall Armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda)

- Red-Necked Peanutworm Moth (Stegasta bosqueella)

The beetle and true bug pests consumed by bats were:

- Hairy Fungus Beetle (Typhaea stercorea)

- Tarnished Plant Bug (Lygus lineolaris)

- Two-lined Spittlebug (Prosapia bicincta)

Three of these pests (Soybean Looper, Beet Armyworm, and Two-lined Spittlebug) were most often consumed by pregnant and juvenile bats. This is good news for growers of crops affected by these pests because you have a sound option for increasing the likelihood of bats helping control them. The trick is to provide the conditions that adult female bats like near the crops these pests feed on (e.g., soybeans, peanut, cotton, corn, sorghum, safflower). Most female bats pick a maternity roost in early spring. A maternity roost is a structure that provides warm, dry, dark conditions for female bats to sleep in during the day, and it is ultimately where they give birth to pups. When selecting a site to set up a maternity roost, female bats look for structures that are large enough to provide shelter for a large number of bats. A roomy structure can accommodate many bats, which allows the flightless pups to keep each other warm while the mothers fly in search of food at night. Installing a bat house like those shown here can provide conditions appropriate for a maternity colony, increasing your chances of having bats help control these insect pests.

Another useful strategy for enhancing pest control services by bats involves creating or maintaining structures that could serve as natural roost sites for bats. The natural structures bats prefer include large trees with cavities, dead and dying trees with peeling bark, oak trees with Spanish moss, and palm trees allowed to maintain their dead fronds. In agricultural areas and suburban areas these types of trees are often in short supply.

Maintaining large, old trees of a mix of species, and supplementing with bat houses, can help ensure there are plenty of roosting options for bats. This, in turn, will increase the likelihood that bats are available to assist with your pest management.

by Carrie Stevenson | Sep 27, 2019

Ospreys, or fish hawks, build their nests from sticks atop dead trees. Photo credit: UF IFAS Extension

Big hurricanes like Dorian (Bahamas) and 2018’s Michael (central Florida Panhandle) were devastating to the communities they landed in. Flooding, wind, rain, loss of power and communications eventually made way for ad hoc clearing and cleanup, temporary shelters, and a slow walk to recovery. Among the most striking visual impacts of a hurricane are the tree losses, as there are unnatural openings in the canopy and light suddenly shines on areas that had been shaded for years. In northwest Florida, pines are particularly vulnerable. After any hurricane in the Panhandle, you can drive down Interstate 10 for miles and see endless pines blown to the ground or broken off at the top. During Hurricane Ivan 15 years ago, the coastal areas in Escambia and Santa Rosa lost thousands of trees not only due to wind, but also to tree roots inundated by saltwater for long periods.

Dead trees left by hurricanes serve as ideal nesting ground for large birds like ospreys. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Nature always finds a way, though. Because of all those dead (but still-standing) pines, our osprey (Pandion haliaetus) population is in great shape in the Pensacola area. How are these two things related? Well, ospreys build large stick nests in the tall branches/crooks of dead trees, known as snags. They particularly prefer those near the water bodies where they fish. When I first moved here 20 years ago, I rarely saw ospreys. Now, it’s uncommon not to see them near the bayous and bays, or to hear their high-pitched calls as they swoop and dive for fish.

If you are not familiar with ospreys, they can be distinguished by their call and their size (up to six foot wingspan). It is common to see them in their large nests atop those snags, flying, or diving for fish. I usually see them with mullet in their talons, although they also prey on catfish, spotted trout, and other smaller species. They have white underbellies, brown backs, and are smaller than eagles but larger than your average hawk. One of their more interesting physical adaptations (and identifying characteristics) is their ability to grip fish parallel to their bodies, making it more aerodynamic than the perpendicular method most birds use.

Ospreys mate for life, and cooperate to build nests and care for young. The species has overcome many complex threats—including DDT damage to eggs and habitat loss—but the sight of them flying is always inspiring to me. They are a living embodiment of resilience amidst adversity.

by Les Harrison | Sep 27, 2019

Pokeweed is currently producing many purple berries containing seed ready for avian distribution.

Half a century ago the AM airwaves included a tune by a rock singer who crooned about Polk Salad Annie. While not exactly epic lyrics, it did have a catchy beat which made it to number eight on Billboard’s Hot 100.

The basis of this dish was common pokeweed (Phytolacca americana), a native of North American perennial weed frequently found in pastures as well as fence-rows, fields, wooded areas and neglected residential landscapes.

The reason this plant is only on the menu of the economically distress is all parts of it contain saponins, oxalates, and the alkaloid toxin phytolacine. The roots and seeds of this species contain the highest concentrations of these compounds.

As winter moves to spring, this plant is emerging from its winter dormancy. The warm summer of 2019 has accelerated the regrowth in north Florida and the surrounding states.

Once pokeweed becomes established, it regrows each year from a large, fleshy taproot which penetrates over a foot deep. The crown of the root is where the plant is regenerated and can be as large as five and a half inches in diameter at the soil surface within two growing seasons.

Pokeweed usually has a red trunk like stem, which becomes hollow as the plant matures later in the year. Leaves become quite large as the plant grows to its full potential and are the basis for the Polk salad.

The process for rendering the leave edible by humans, or other mammals, involves boiling and washing with a second boiling and more washing. Short of eminent starvation, it is not a good or safe meal choice for dining.

When in bloom the individual flowers appear green to white and are typically missing petals. Fruits are green when immature and turn a deep purple to black at maturity which is the basis for one alternate name for this species, inkberry.

Each fruit contains about nine small, hard-shelled seeds. Pokeweed can produce a few thousand seeds to over 48,000 seeds per plant annually.

In the right situation these seeds may remain viable in the soil for over four decades (40 years). When exposed to favorable environmental conditions the seed sprout and the process is repeated.

While not a suitable selection for people or livestock, birds eat the fruits without much evidence of harm and are usually the means for seed dispersal. Roosting sites along fence rows and under utility lines frequently show signs of seed deposits.

In addition to feeding cardinals, mocking birds, cedar waxwings and other avian species, the pokeweed is host to a variety of insects. Some are beneficial and others are not.

A number of caterpillars utilize this weed to sustain their larval stage of development. Unfortunately, some other less desirable insects use the local weed, too.

Pokeweed can act as reservoirs of various viruses transmitted by insects which are destructive to vegetable and ornamental plants. Whiteflies and aphids are the main culprits, but other insect species can contribute the disease issue.

Old rock tunes aside, it is best to leave the pokeweed and Polk salad to the bugs and birds.

To learn more about pokeweed read the UF/IFAS publication COMMON POKEWEED.

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.

As the migratory birds stop off or stay in the Panhandle this winter, they need to find food, food and more food. There is a wide variety of migration activity in Florida beginning in the fall months of September, October, and November. From woodland song birds to waterfowl to the annual warbler invasion, so many different species show up in Florida. While year-to-year migration patterns and winter foraging grounds can shift for some species due to a variety of reasons, some birds stay in Florida for the winter months of December, January, and February. Some may arrive early and others may stay late.