by Shep Eubanks | Sep 12, 2018

North Florida buck feeding on acorns at the edge of a food plot. Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

It’s that time of year when landowners, hunters, and other wildlife enthusiasts begin to plan and prepare fall and winter food plots to attract wildlife like the nice buck in the photo.

Annual food plots are expensive and labor intensive to plant every year and with that thought in mind, an option you may want to consider is planting mast producing crops around your property to improve your wildlife habitat. Mast producing species are of two types of species, “hard mast” (oaks, chestnut, hickory, chinkapin, American Beech, etc.), and “soft mast” (crabapple, persimmon, grape, apple, blackberry, pears, plums, pawpaws, etc.). There are many mast producing trees and shrubs that can be utilized and will provide food and cover for a variety of wildlife species. This article will focus on two, sawtooth oak (or other oaks) and southern crabapple.

Sawtooth Oak

Oaks are of tremendous importance to wildlife and there are dozens of species in the United States. In many areas acorns comprise 25 to 50% of a wild turkeys diet in the fall (see photos 1, 2, and 3) and probably 50% of the whitetail deer diet as well during fall and winter. White oak acorns average around 6% crude protein versus 4.5% to 5% in red oak acorns. These acorns are also around 50% carbohydrates and 4% fat for white oak and 6% fat for red oak.

The Sawtooth Oak is in the Red Oak family and typically produces acorns annually once they are mature. The acorns are comparable to white oak acorns in terms of deer preference as compared to many other red oak species. Most red oak acorns are high in tannins reducing palatability but this does not seem to hold true for sawtooth oak. They are a very quick maturing species and will normally begin bearing around 8 years of age. The acorn production at maturity is prolific as you can see in the photo and can reach over 1,000 pounds per tree in a good year when fully mature. They can reach a mature height of 50 to 70 feet. There are two varieties of sawtooth oak, the original sawtooth and the Gobbler sawtooth oak, which has a smaller acorn that is better suited for wild turkeys. The average lifespan of the sawtooth oak is about 50 years

Photo 1 – Seventeen year old planting of sawtooth oaks in Gadsden County Florida. Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

Photo 2 – Gadsden County gobblers feeding on Gobbler sawtooth oak acorns

Photo Credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

Photo 3 – Gobbler sawtooth oak acorns in Gadsden County. Notice the smaller size compared to the regular sawtooth oak acorn which is the size of a white oak acorn.

Photo credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

Southern Crabapple

Southern Crabapple is one of 25 species of the genus Malus that includes apples. They generally are well adapted to well drained but moist soils and medium to heavy soil types. They will grow best in a pH range of 5.5 – 6.5 and prefer full sun but will grow in partial shade as can be seen in photo 4. They are very easy to establish and produce beautiful blooms in March and April in our area as seen in photo 5. There are many other varieties of crabapples such as Dolgo that are available on the market in addition to southern and will probably work very well in north Florida. The fruit on southern crabapple is typically yellow green to green and average 1 to 1.5 inches in diameter. They are relished by deer and normally fall from the tree in early October.

Photo 4 – Southern crabapple tree planted on edge of pine plantation stand. Photo taken in late March during bloom.

Photo credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

Photo 5 – Showy light pink to white bloom of southern crabapple in early April during bloom.

Photo credit – Shep Eubanks UF/IFAS

A good resource publication on general principles related o this topic is Establishing and Maintaining Wildlife Food Sources.

If you are interested in planting traditional fall food plots check out this excellent article by UF/IFAS Washingon Couny Extension Agent Mark Mauldin: Now’s the Time to Start Preparing for Cool-Season Food Plots .

For more information on getting started with food plots in your county contact your county’s UF/IFAS Extension Office

by Laura Tiu | Aug 3, 2018

Written By: Laura Tiu, Holden Harris, and Alexander Fogg

Non-containment lionfish traps being tested by the University of Florida offshore Destin, FL. Invasive lionfish are attracted to the lattice structure, then captured by netting when the trap is pulled from the sea floor. The trap may have the potential to control lionfish densities at depths not accessible by SCUBA divers. [ALEX FOGG/CONTRIBUTED PHOTO]

Red lionfish (Pterois volitas / P. miles) are a popular aquarium fish with striking red and white strips and graceful, butterfly-like fins. Native to the Indo-Pacific region, lionfish were introduced into the wild in the mid-1980s, likely from the release of pet lionfish into the coastal waters of SE Florida. In the early 2000s lionfish spread throughout the US eastern seaboard and into the Caribbean, before reaching the northern Gulf of Mexico in 2010. Today, lionfish densities in the northern Gulf are higher than anywhere else in their invaded range.

Invasive lionfish negatively affect native reef communities. They consume and compete with native reef fish, including economically important snappers and groupers. Their presence has shown to drive declines in native species and diversity. Lionfish possess 18 venomous spines that appear to deter native predators. The interaction of invasive lionfish with other reef stressors – including ocean acidification, overfishing, and pollution – is of concern to scientists.

Lionfish harvest by recreational and commercial divers is currently the best means of controlling their densities and minimizing their ecological impacts. Lionfish specific spearfishing tournaments have proven successful in removing large amounts in a relatively short amount of time. This year’s Lionfish Removal and Awareness Day removed almost 15,000 lionfish from the Northwest Florida waters in just two days. Lionfish is considered to be an excellent quality seafood, and they are now being targeted by a handful of commercial divers. Several Florida restaurants, seafood markets, and grocery stores chains are now regularly serving lionfish.

While diver removals can control localized lionfish densities, the problem is that lionfish also inhabit reefs much deeper than those that can be accessed by SCUBA divers. Surveys of deepwater reefs show lionfish have higher densities and larger body sizes than lionfish on shallower reefs. In the Gulf of Mexico, the highest densities of lionfish surveyed were between 150 – 300 feet. While SCUBA diving is typically limited to less than 130 feet, lionfish have been observed deeper than 1000 feet.

For the past several years, researchers have been working to develop a trap that may be able to harvest lionfish from deep water. Dr. Steve Gittings, Chief Scientist for the Office of National Marine Sanctuaries at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, has spearheaded the design for a “non-containment” lionfish trap. The design works to “bait” lionfish by offering a structure that attracts them. The trap remains open while deployed on the sea floor, allowing fish to move in and out of the trap footprint. When the trap is retrieved, a netting is pulled up around

Deep water lionfish traps being tested by the University of Florida offshore Destin, FL. [ALEX FOGG/CONTRIBUTED PHOTO]

The researchers are headed offshore to retrieve, redeploy, and collect data on the lionfish traps. Twelve non-containment traps are currently being tested offshore NW Florida. The research is supported by a grant from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. The study will try to answer important questions for a new method of catching lionfish: where and how can the traps be most effective? How long should they be deployed? And, is there any bycatch (accidental catch of other species)?

Recent trials have proved successful in attracting lionfish to the trap with minimal bycatch. Continued research will hone the trap design and assess how deployment and retrieval methods may increase their effectiveness. If successful in testing, lionfish traps may become permitted for use by commercial and recreational fisherman. The traps could become a key tool in our quest to control this invasive species and may even generate income while protecting the deepwater environment.

Outreach and extension support for the UF’s lionfish trap research is provided by Florida Sea Grant. For more information contact Dr. Laura Tiu, Okaloosa and Walton Counties Sea Grant Extension Agent, at lgtiu@ufl.edu / 850-689-5850 (Okaloosa) / 850-892-8172 (Walton).

by Sheila Dunning | Jul 23, 2018

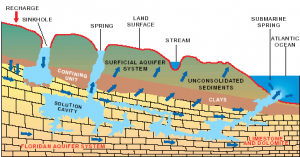

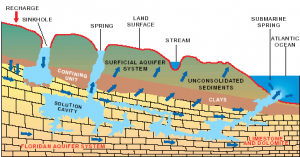

Hydrologic cycle and geologic cross-section image courtesy of Florida Geological Survey Bulletin 31, updated 1984.

With more than 250 crystal clear springs in Northwest Florida it is just a short road trip to a pristine swimming hole! Springs and their associated flowing water bodies provide important habitat for wildlife and plants. Just as importantly, springs provide people with recreational activities and the opportunity to connect with the natural environment. While paddling your kayak, floating in your tube, or just wading in the cool water, think about the majesty of the springs. They are the visible part of the Florida Aquifer, the below ground source of most Florida’s drinking water.

A spring is a natural opening in the Earth where water emerges from the aquifer to the soil surface. The groundwater is under pressure and flows upward to an opening referred to as a spring vent. Once on the surface, the water contributes to the flow of rivers or other waterbodies. Springs range in size from small seeps to massive pools. Each can be measured by their daily gallon output which is classified as a magnitude. First magnitude springs discharge more than 64.6 million gallons of water each day. Florida has over 30 first magnitude springs. Four of them can be found in the Panhandle – Wakulla Springs and the Gainer Springs Group of 3.

Wakulla Springs is located within Edward Ball Wakulla Springs State Park. The spring vent is located beneath a limestone ledge nearly 180 feet below the land surface. Archaeological evidence suggests that humans have utilized the area for nearly 15,000 years. Native Americans referred to the area as “wakulla” meaning “river of the crying bird”. Wakulla was the home of the Limpkin, a rare wading bird with an odd call.

Over 1,000 years ago, Native Americans used another first magnitude spring, the Gainer Springs group that flow into the Econfina River. “Econfina”, or “natural bridge” in the local native language, got its name from a limestone arch that crossed the creek at the mouth of the spring. General Andrew Jackson and his Army reportedly used the natural bridge on their way west exploring North America. In 1821, one of Jackson’s surveyors, William Gainer, returned to the area and established a homestead. Hence, the naming of the waters as Gainer Springs.

Three major springs flow at 124.6 million gallons of water per day from Gainer Springs Group, some of which is bottled by Culligan Water today. Most of the springs along the Econfina maintain a temperature of 70-71°F year-round. If you are in search of something cooler, you may want to try Ponce de Leon Springs or Morrison Springs which flows between 6.46 and 64.6 million gallons a day. They both stay around 67.8°F. Springs are very cool, clear water with such an importance to all living thing; needing appreciation and protection.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 23, 2018

Local estuaries are a beautiful place to explore with your family. Credit: Matthew Deitch, UF IFAS Extension

Florida’s rivers, springs, wetlands, and estuaries are central features to the identity of northwest Florida. They provide a wide range of services that benefit peoples’ health and well-being in our region. They create recreational opportunities for swimmers, canoers, and kayakers; support diverse wildlife for birders and plant enthusiasts; sustain a vibrant commercial and recreational fishery and shellfishery; serve as corridors for shipping and transportation; and support ecosystems that help to improve water quality. Maintaining these aquatic ecosystem services requires a low level of chemical inputs from the upstream areas that comprise their watersheds.

Aquatic ecosystems are especially sensitive to nitrogen and phosphorus, which are key nutrients for the growth of plants, algae, and bacteria that live in these waters. High levels of these nutrients combined with our sunny weather and warm summer temperatures create conditions that can lead to rapid growth of aquatic plants and algae, which can cover these water bodies and make them no longer enjoyable for people and wildlife. It can also cause dissolved oxygen levels to fall, as plants respire (especially at night, when they are not photosynthesizing) and as bacteria consume oxygen to break down dead plant material. Low dissolved oxygen can create conditions that are deadly for fish and shellfish.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) lists more than 1,400 water bodies (including rivers, springs, wetlands, and estuaries) as impaired by pollutants. Many of these are impaired by excessive nitrogen or phosphorus. It is a daunting challenge to reduce pollutants in these water bodies because their inputs frequently come from all over the landscape, rather than a specific point—nutrients can come from agricultural fields, residential landscapes, septic tanks, atmospheric deposition, and livestock throughout the watershed.

In Florida, FDEP has begun a program to reduce nutrient concentrations in impaired watersheds by collaborating with landowners and other stakeholders to develop management programs to reduce pollutants entering the state’s waters. This pollutant reduction program is currently focused on Florida’s spring systems, including Jackson Blue Spring and Merritt’s Mill Pond in Jackson County. Merritt’s Mill Pond is a 4-mile long, 270-acre pond located near Marianna, and it is a popular regional destination for swimming, boating, kayaking, and fishing in the Panhandle. Its main source is Jackson Blue Spring, which produces, on average, more than 70 million gallons of water each day. Excessive growth of aquatic plants and algae in the pond during summer reduces the area available for swimming and boating. In 2014, FDEP began working with agricultural producers, residents, developers, local government officials, and other stakeholders to identify nutrient contributions in the Merritt’s Mill Pond watershed and develop an action plan to reduce nutrients entering the pond in the coming decades. Collaborations with stakeholders help to improve the accuracy of pollutant estimates, and to ensure the plan is designed appropriately to achieve desired ecological outcomes.

This Action Plan for reducing nutrients into Merritt’s Mill Pond provides an opportunity for land managers to implement their own plans to reduce nutrient contributions without FDEP imposing rigid regulations or mandating particular actions. People can choose from an array of Best Management Practices designed to reduce nutrient contributions, and the state has made funds available for people to help implement these plans. Implementing this Action Plan will restore the wonders of Merritt’s Mill through the 21st Century.

This article was written by: Matthew J Deitch, PhD, Assistant Professor, Watershed Management with the UF IFAS Soil and Water Sciences Department at the West Florida Research and Education Center. For more information, you can contact him at mdeitch@ufl.edu or 850-377-2592.

by Rick O'Connor | May 31, 2018

It is now late May and in recent weeks I, and several volunteers, have been surveying the area for terrapins, horseshoe crabs, and monitoring local seagrass beds. We see many creatures when we are out and about; one that has been quite common all over the bay has been the “stingray”.

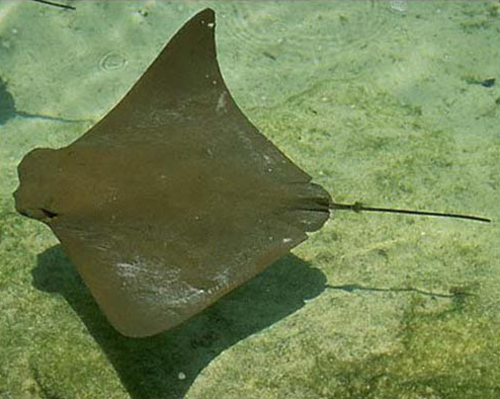

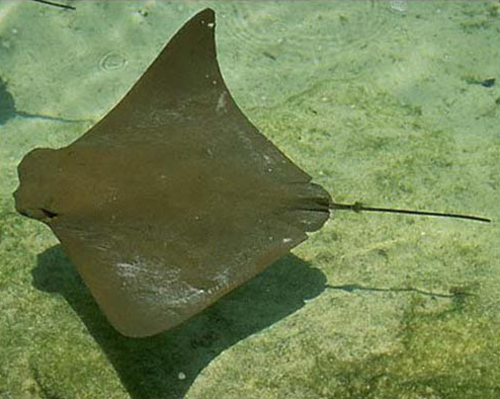

The cownose ray is often mistaken for the manta ray. It lacks the palps (“horns”) found on the manta.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

These are intimidating creatures… everyone knows how they can inflict a painful wound using the spine in their tail, but may are not aware that not all “stingrays” can actually use a spine to drive you off – actually, not all “rays” are “stingrays”.

So what is a ray?

First, they are fish – but differ from most fish in that they lack a bony skeleton. Rather it is cartilaginous, which makes them close cousins of the sharks.

So what is the difference between a shark and a ray?

You would immediately jump on the fact that rays are flat disked-shape fish, and that sharks are more tube-shaped and fish like. This is probably true in most cases, but not all. The characteristics that separate the two groups are

- The five gill slits of a shark are on the side of the head – they are on the ventral side (underside) of a ray

- The pectoral fin begins behind the gill slits in sharks, in front of for the ray group

Not all rays have the whip-like tail that possess a sharp spine; some in fact have a tube-shaped body with a well-developed caudal fin for a tail.

There are eight families and 19 species of rays found in the Gulf of Mexico. Some are not common, but others are very much so.

Sawfish are large tube-shaped rays with a well-developed caudal fin. They are easily recognized by their large rostrum possessing “teeth” giving them their common name. Walking the halls of Sacred Heart Hospital in Pensacola, you will see photos of fishermen posing next to monsters they have captured. Sawfish can reach lengths of 18 feet… truly intimidating. However, they are very slow and lethargic fish. They spend their lives in estuaries, rarely going deeper than 30 feet. They were easy targets for fishermen who displayed them as if they caught a true monster. Today they are difficult to find and are protected. There are still sightings in southwest Florida, and reports from our area, but I have never seen one here. I sure hope to one day. There are two species in the Gulf of Mexico.

Guitarfish are tube-shaped rays that are very elongated. They appear to be sharks, albeit their heads are pretty flat. They more common in the Gulf than the bay and, at times, will congregate near our reefs and fishing piers to breed. They are often confused with the electric rays called torpedo rays, but guitarfish lack the organs needed to deliver an electric shock. They have rounded teeth and prefer crustaceans and mollusk to fish. There is only one species in the Gulf.

Torpedo rays can deliver an electric shock – about 35 volts of one. Though there are stories of these shocking folks to death, I am not aware of any fatalities. Nonetheless, the shock can be serious and beach goers are warned to be cautious. I once mistook one buried in the sand for a shell. Let us just say the jolt got my attention and I may have had a few words for this fish before I returned to the beach. We have two species of torpedo rays in the Gulf of Mexico.

Skates look JUST like stingrays – but they lack the whip-like tail and the venomous spine that goes with it. They are very common in the inshore waters of the Florida Panhandle and though they lack the terrifying spine we are all concerned about, they do possess a series of small thorn-like spine on the back that can be painful to the bare foot of a swimmer. Skates are famous for producing the black egg case folks call the “mermaids’ purse”. These are often found dried up along the shore of both the Gulf and they bay and popular items to take home after a fun day at the beach. There are four species of skates found in the Gulf of Mexico.

Stingrays… this is the one… this is the one we are concerned about. Stingrays can be found on both sides of our barrier islands and like to hide beneath the sand to ambush their prey. More often than not, when we approach they detect this and leave. However, sometimes they will remain in the sand hoping not to be detected. The swimmer then steps on their backs forcing them to whip their long tail over and drive the serrated spine into your foot. This usually makes you move off them – among other things. The piercing is painful and spine (which is actually a modified tooth) possesses glands that contain a toxic substance. It really is no fun to be stung by these guys. Many people will do what is called the “stingray shuffle” as they move through the water. This is basically sliding your feet across the sand reducing your chance of stepping on one. They are no stranger to folks who visit St. Joe Bay. The spines being modified teeth can be easily replaced after lodging in your foot. Actually, it is not uncommon to find one with two or three spines in their tails ready to go. Stingrays do not produce “mermaids’ purses” but rather give live birth. There are five species in the Gulf of Mexico.

The Atlantic Stingray is one of the common members of the ray group who does possess a venomous spine.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

Butterfly ray is a strange looking fish and easy to recognize. The wide pectoral fins and small tail gives it the appearance of a butterfly. Despite the small tail, it does possess a spine. However, the small tail makes it difficult for the butterfly ray to pierce you with it. There is only one species in the Gulf, the smooth butterfly ray.

Eagle rays are one of the few groups of rays that actually in the middle of the water column instead of sitting on the ocean floor. They can get quite large and often mistaken for manta rays. Eagle rays lack the palps (“horns”) that the manta ray possesses. Rather they have a blunt shaped head and feed on mollusk. They do have venomous spines but, as with the butterfly ray, their tails are too short to extend and use it the way stingrays do. There are two species. The eagle ray is brown and has spots all over its back. The cownose ray is very common and almost every time I see one, I hear “there go manta rays”… again, they are not mantas. They have a habit of swimming in the surf and literally body surfing. Surfers, beachcombers, and fishermen frequently see them.

Last but not least is the very large Manta ray. This large beast can reach 22 feet from wingtip to wing tip. Like eagle rays, they swim through the ocean rather than sit on the bottom. They have to large “horns” (called palps) that help funnel plankton into their mouths. These horns give them one of their common names – the devilfish. Mantas, like eagle and butterfly rays, do have whip-like tails and a venomous spine, but like the above, their tails are much shorter and so effective placement of the spine in your foot is difficult.

Many are concerned when they see rays – thinking that all can inflict a painful spine into your foot – but they are actually really neat animals, and many are very excited to see them.

References

Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M. College Station, TX. pp. 327.

Shipp, R. L. 2012. Guide to Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico. KME Seabooks. Mobile AL. pp. 250.

by Laura Tiu | May 12, 2018

Are you interested in learning about marine life, going fishing, or exploring the underwater world with a mask and snorkel? If so, this is the camp for you! This local education opportunity for budding marine scientists will be happening this summer at Camp Timpoochee in Niceville, FL. The camps enable participants to explore the marine and aquatic ecosystems of Northwest Florida; especially that of the Choctawhatchee Bay. Campers get to experience Florida’s marine environment through fishing, boating snorkeling, games, STEM (science, technology, engineering & math) activities and other outdoor adventures. University of Florida Sea Grant Marine Agents and State 4-H Staff partner to provide hands-on activities exploring and understanding the coastal environment.

Sampling the benthic community at Timpoochee.

Florida Sea Grant has a long history of supporting environmental education for youth and adults to help them become better stewards of the coastal zone. This is accomplished by providing awareness of how our actions affect the health of our watersheds, oceans and coasts and marine camp is a great opportunity for sharing that information. Many of the Sea Grant youth activities use curriculum developed by the national Sea Grant program and geared toward increasing student competency in math, science, chemistry and biology. The curriculum is fun and interesting!

Marine Camp is open to 4-H members and non 4-H members between the ages of 8-13 (Junior Camp) and, new this year, ages 14-17 (Senior Camp). There will be two Junior Camps in 2018. The July 23-27 camp is full, but there are still openings for the June 25-29 session. The cost for Junior Marine Camp is $275.00 for the week. A more intensive Senior Marine Camp has been scheduled for July 16-20. This camp will contain a community service component and costs $300 for the week.

If Marine Camp sounds interesting to someone you know, visit the Camp Timpoochee website at http://florida4h.org/camps_/specialty-camps/marine/ for the 2018 dates and registration instructions. A daily snack from the canteen and a summer camp T-shirt are included in the camp fees, along with three nutritious meals per day prepared on site by our certified food safety staff. All cabins are air-conditioned. So many surprises await at marine camp, come join the fun.

Seining the sea grass at Timpoochee.

Larval fish in the Timpoochee oyster reef.