by Les Harrison | Dec 8, 2017

A great walk or ride is close at hand on this trail which once supported a critical 19th century transportation link.

The typical image of a state park is that of a place where visitors enter through a front gate and enjoy the wonders of nature or some historic structure. The Tallahassee-St. Marks Historic Railroad State Trail, which is run by The Florida Division of Recreation and Parks, is truly an exception to the typical model.

While many parks have trails, this one runs 20.5 miles from Tallahassee to the coastal community of St. Marks. This area is the first rail-trail in the Florida’s system of greenways and trails to be paved providing a scenic experience for running, walking, bicycling and skating.

Additionally, horseback riding occurs on the adjacent unpaved trail. Because of its outstanding qualities, this state trail has been selected as a National Recreation Trail.

The origins of this 21st century recreational site date back to before Florida was a state. The Tallahassee Railroad Company was approved in 1835 by the territorial legislative council and received the first federal land grant to a railroad for construction of the line.

Cotton and other commodities moved from the Tallahassee region to the port of St. Marks for shipment to the north east U.S. and to Great Brittan. Raw cotton was the major generator of foreign exchange during the antebellum years, so this railroad was a critical economic link in the area’s development.

Fast forward to 1983, that is when the Seaboard Coastline filed the papers to abandon the line and end service. After 147 years, the longest-operating railroad in Florida was deemed economically unfeasible to operate.

It was not out of service for long. In 1984 the corridor was purchased by the Florida Department of Transportation, and the rest is history.

Visitors can access the trail in multiple locations along the way. Parking areas are provided at many locations along the trail with mileage markers make available distance information and the trail corridor is lined with trees providing plenty of shade.

Restroom facilities are placed at intervals along the trail. There are picnic pavilions and a playground at the Wakulla Station Trailhead.

The trail is open from 8:00 a.m. until sundown, 365 days a year and there is no use fee required. Donations which aid with the promotion and upkeep are accepted.

For more information on the St. Marks Trail, contact the park office at (850) 487-7989 or Tallahassee-St. Marks Historic Railroad State Trail.

While the historic structures are gone, it is a great way to enjoy nature’s wonders close to the coast.

by Laura Tiu | Nov 20, 2017

The lodge at Camp Helen State Park was the perfect backdrop for the Coastal Dune Lake Seminar Series Water School. Brandy Foley of the Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance shares her paleolimnology research work on the lakes.

On a beautiful October day, 35 people gathered at the Camp Helen State Park lodge to share information about the rare Coastal Dune Lakes (CDLs) that line the coast of Walton and Bay Counties. Organized by the University of Florida Extension Programs in Bay and Walton counties, the Water School included a morning seminar series featuring speakers from various groups that work together to support the lakes. Laura Tiu, Sea Grant Agent for Walton and Okaloosa counties started off the day giving a broad overview of the history and ecology of the lakes. Brandy Foley of the Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance shared her research on the paleolimnology, or study of the lake sediments over time, of two coastal dune lakes. Clayton Iron Wolf, a ranger at Camp Helen, gave a summary of the importance of Lake Powell and its benefit to the park. Jeff Talbert of the Atlanta Botanical Garden thrilled attendees with his pictures and research on the Deer Lake State Park restoration project. Norm Capra, who wears many hats, including that of the Lake Powell Community Alliance and Friends of Camp Helen State Park, shared the work they have done promoting conservation of shorebirds there. Dr. Dana Stephens, Director of the Mattie Kelly Environmental Institute at Northwest Florida State College shared analyses of many years of water chemistry and quality data collected on the lakes. Melinda Gates, Environmental Specialist for Walton County, wrapped up with a presentation on the efforts to protect and preserve the lakes.

The attendees seemed pleased with the event with one hundred percent of attendees rating the quality of information presented, usefulness of information, speakers’ knowledge, overall value of the program, and quality of location as good or excellent. The seminar helped attendees identify important roles of the CDLs in the ecosystem and understand why it is important to protect them. Several participants plan to make behavior changes based in the workshop including: joining or volunteering with Choctawhatchee Basin Alliance, Audubon, Sierra Club or Lake Watch Volunteers; sharing the information; living minimally; and engaging in activism. The seminar was followed by a kayak tour lead by Scott Jackson, Bay County Sea Grant Agent, to the outflow of Lake Powell and a visit to a faux sea turtle nest demonstration by Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission. This Water School was part of a regional series offered by UF/IFAS Extension. For more information on future schools, please subscribe to our Panhandle Outdoors Newsletter.

by Carrie Stevenson | Nov 3, 2017

Red mangrove growing among black needlerush in Perdido Key. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Discovering something new is possibly the most exciting thing a field biologist can do. As students, budding biologists imagine coming across something no one else has ever noticed before, maybe even getting the opportunity to name a new bird, fish, or plant after themselves.

Well, here in Pensacola, we are discovering something that, while already named and common in other places, is extraordinarily rare for us. What we have found are red mangroves. Mangroves are small to medium-sized trees that grow in brackish coastal marshes. There are three common kinds of mangroves, black (Avicennia germinans), white (Laguncularia racemosa), and red (Rhizophora mangle).

Black mangroves are typically the northernmost dwelling species, as they can tolerate occasional freezes. They have maintained a large population in south Louisiana’s Chandeleur Islands for many years. White and red mangroves, however, typically thrive in climates that are warmer year-round—think of a latitude near Cedar Key and south. The unique prop roots of a red mangrove (often called a “walking tree”) jut out of the water, forming a thick mat of difficult-to-walk-through habitat for coastal fish, birds, and mammals. In tropical and semi-tropical locations, they form a highly productive ecosystem for estuarine fish and invertebrates, including sea urchins, oysters, mangrove and mud crabs, snapper, snook, and shrimp.

Interestingly, botanists and ecologists have been observing an expansion in range for all mangroves in the past few years. A study published 3 years ago (Cavanaugh, 2014) documented mangroves moving north along a stretch of coastline near St. Augustine. There, the mangrove population doubled between 1984-2011. The working theory behind this expansion (observed worldwide) is not necessarily warming average temperatures, but fewer hard freezes in the winter. The handful of red mangroves we have identified in the Perdido Key area have been living among the needlerush and cordgrass-dominated salt marsh quite happily for at least a full year.

Key deer thrive in mangrove forests in south Florida. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Two researchers from Dauphin Island Sea Lab are planning to expand a study published in 2014 to determine the extent of mangrove expansion in the northern Gulf Coast. After observing black mangroves growing on barrier islands in Mississippi and Alabama, we are working with them to start a citizen science initiative that may help locate more mangroves in the Florida panhandle.

So what does all of this mean? Are mangroves taking over our salt marshes? Where did they come from? Are they going to outcompete our salt marshes by shading them out, as they have elsewhere? Will this change the food web within the marshes? Will we start getting roseate spoonbills and frigate birds nesting in north Florida? Is this a fluke due to a single warm winter, and they will die off when we get a freeze below 25° F in January? These are the questions we, and our fellow ecologists, will be asking and researching. What we do know is that red mangrove propagules (seed pods) have been floating up to north Florida for many years, but never had the right conditions to take root and thrive. Mangroves are native, beneficial plants that stabilize and protect coastlines from storms and erosion and provide valuable food and habitat for wildlife. Only time will tell if they will become commonplace in our area.

If you are curious about mangroves or interested in volunteering as an observer for the upcoming study, please contact me at ctsteven@ufl.edu. We enjoy hearing from our readers.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 11, 2017

Our first POL program will happen this week – August 17 – at the Navarre Beach snorkel reef, and is sold out! We are glad you all are interested in these programs.

Well! We have another one for you. The Natural Resource Extension Agents from UF IFAS Extension will be holding a two-day water school at St. Joseph Bay. Participants will learn all about the coastal ecosystems surrounding St. Joe Bay in the classroom, snorkeling, and kayaking. Kayaks and overnight accommodations are available for those interested. This water school will be September 19-20. For more information contact Extension Agent Ray Bodrey in Gulf County or Erik Lovestrand in Franklin. Information and registration can be found at https://stjosephbay-waterschool.eventbrite.com.

by Scott Jackson | Jul 14, 2017

The St Andrew Bay pass jetty is more like a close family friend than a collection of granite boulders. The rocks protect the inlet ensuring the vital connections of commerce and recreation. One of the treasured spots along the jetty is known locally as the “kiddie pool”, which is accessible from St Andrew’s State Park. There are similar snorkeling opportunities throughout northwest Florida. Jetties provide an opportunity to explore hard substrate or rocky marine ecosystems. These rocks are home to a variety of colorful sub-tropical and migrating tropical fish.

Snorkelers and divers who visit are likely to see a variety fish like sergeant majors, blennies, surgeon and doctor fish, just to name a few. Photo by L Scott Jackson.

Exploring a jetty is more like a sea-safari adventure than an experience in a real swimming pool – it is a natural place full of potential challenges that first time visitors need to prepare to encounter.

Divers and snorkelers are required to carry dive flags when venturing beyond designated swimming areas. These flags notify boaters that people are in the water. Brightly colored snorkel vests are not only good safety gear but they help you rest in the water without standing on rocks which are covered in barnacles and sometimes spiny sea urchins.

According to the Florida Department of Health, most sea urchin species are not toxic but some Florida species like the Long Spined Sea Urchin have sharp spines can cause puncture injuries and have venom that can cause some stinging. Swim and step carefully when snorkeling as they usually are attached to rocks, both on the bottom and along jetty ledges. Photo by L Scott Jackson

Dive booties also help protect your feet. I found out the hard way! A couple of years ago my foot hit against a sea urchin puncturing my heel. The open back of my dive fin did not provide any protection resulting in a trip to the urgent care doctor. My daughter later teased it was an “urchin care” doctor! Sea urchin spines are brittle and difficult to remove, even for a doctor. Lesson Learned: “Prevention is the best medicine”.

After a couple of weeks of limping around and a course of antibiotics, I recovered ready to return one of my favorite watery places – a little wiser and more prepared. I now bring a small first aid kit, just in-case, to help take care of small scrapes, cuts, and other minor injuries.

Gloves are recommended to protect hands from barnacle cuts and scrapes. Shirts like a surfing rash guard or those made from soft material help keep your body temperature warm on long snorkel excursions. Along with sunscreen, shirts also protect against sunburn.

There’s opportunity to see marine life from the time you enter the water with depths for beginning snorkelers at just a few feet deep. Some SCUBA divers also use the jetty for their initial training. Most underwater explorers are instantly hooked, and return for many years to come. Photo by L Scott Jackson

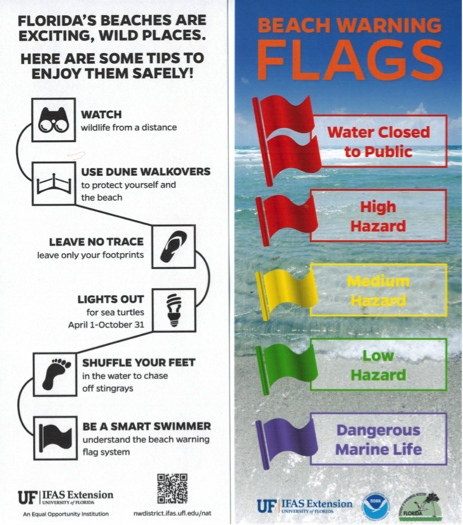

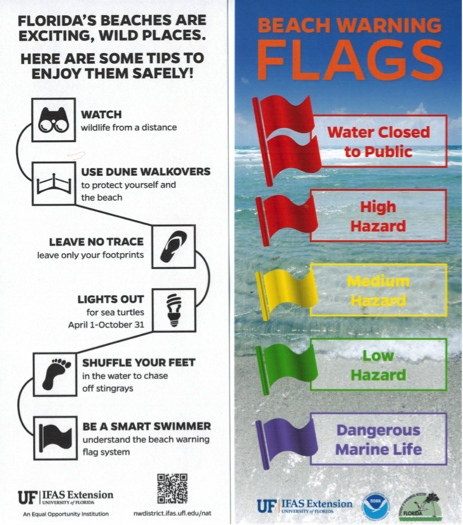

Finally, know the swimming abilities of yourself and your guests, especially when venturing to deeper areas. It’s good to have a dive buddy even when snorkeling. Pair up and watch out for each other. Be aware that currents and seas can change dramatically during the day. Know and obey the flag system. Double Red Flag means no entry into the water. Purple flags indicate presence of dangerous marine life like jellyfish, rays, and rarely even sharks. Local lifeguards and other beach authorities can provide specific details and up to date safety information.

Follow these beach safety tips for helping your family enjoy the beach while protecting coastal wildlife.

An Equal Opportunity Institution. UF/IFAS Extension, University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, Nick T. Place, dean for UF/IFAS Extension. Single copies of UF/IFAS Extension publications (excluding 4-H and youth publications) are available free to Florida residents from county UF/IFAS Extension offices.

by Erik Lovestrand | Jun 30, 2017

Imagine yourself as an early settler, migrating with your family into the area known as La Florida, with the hope of staking a claim and building a new life. You’ve heard stories of horrendous mosquitos, fierce native peoples, deadly snakes, and giant alligators. Regardless, the promise of abundant fish and wildlife, a year-round growing climate and a chance to start anew, override any doubts you might have and you pack your wagon, hitch up your mules and head south with great anticipation.

Florida’s springs are world famous. They attracted native Americans and settlers; as well as tourists and locals today.

Photo: Erik Lovestrand

Well, the mosquitos have been horrendous, one of your mules was bitten by a rattlesnake but survived, and one of your hounds was taken by an alligator at a river crossing. You are in your second month of travel and you’ve come into a strange area of forest that stretches for miles in all directions. Deep, white sands clutch at your wagon wheels and make tough going for the mules. The land is forested by tall majestic pines and the terrain is gently rolling with an open view across a landscape dominated by wiry grasses and other low growing herbaceous plants. The buzzing sound of insects in the trees makes it seem even hotter for some reason and everyone is tired and thirsty as you spy a dark line of hardwood trees just down-slope. You decide to take refuge in the shade to rest the lathered mules and hope for a water source to refill your dangerously low water cask.

As you walk back under the shady canopy you find an obvious trail that has been used by other humans for generations as evidenced by a deep rut worn into the ground between exposed limestone boulders. As luck would have it, you see the glint of water through the trees ahead. When you clear the trees near the water’s edge you stop abruptly in stunned amazement. The image of a deep blue pool of crystal clear water with a small stream exiting into the woods causes you to shake your head in disbelief. You must be dreaming, as you’ve never witnessed such a magical setting; water boiling out of a gaping hole in the earth, surrounded by white sand and long flat blades of grass waving in the current.

Just about everyone who has visited one of our sparkling North Florida springs probably has a similar, magical recollection of their first encounter. As surface water percolates downward through soil layers and the porous karst (limestone) bedrock, it is filtered and cleaned to incredible clarity. The clear water gushing forth in these artesian-spring flows remains 69-70 degrees year-round in our Panhandle springs. This is due to their open aquifer connection, from which many homes draw their drinking water directly.

However, there are some serious vulnerabilities that our springs are facing regarding the quality of the water that they provide for residents and visitors alike. One issue relates to the numerous sink holes throughout our landscape that also connect directly to this same Floridan aquifer. In the past, many of these holes have served as dumping grounds for items ranging from household garbage, to junk cars, old washing machines and refrigerators, and even the occasional murder victim. Imagine all of the pollutants that end up in our drinking water supply as a result of this. Another concern relates to pollution that goes onto the ground surface and ends up in the aquifer. This happens via runoff from paved surfaces, sediments and excess fertilizers or pesticides from the landscape, or even the intentional application of treated wastewater in spray fields located in a “spring-shed.” Water clarity and quality at many of our well-known springs has suffered from excess nutrients that cause algal growth and other unwanted, nuisance plant proliferation.

As we gain a better understanding of how water moves through our landscape and ends up flowing from these natural springs, we should become better stewards by minimizing our human impacts that degrade spring water quality. Let’s keep the magic alive for all of our future generations of nature explorers.