by Laura Tiu | Jun 3, 2017

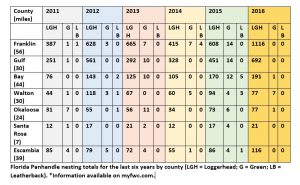

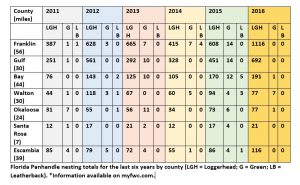

There are five species of sea turtles that nest from May through October on Florida beaches. The loggerhead, the green turtle and the leatherback all nest regularly in the Panhandle, with the loggerhead being the most frequent visitor. Two other species, the hawksbill and Kemp’s Ridley nest infrequently. All five species are listed as either threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Due to their threatened and endangered status, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission/Fish and Wildlife Research Institute monitors sea turtle nesting activity on an annual basis. They conduct surveys using a network of permit holders specially trained to collect this type of information. Managers then use the results to identify important nesting sites, provide enhanced protection and minimize the impacts of human activities.

Statewide, approximately 215 beaches are surveyed annually, representing about 825 miles. From 2011 to 2015, an average of 106,625 sea turtle nests (all species combined) were recorded annually on these monitored beaches. This is not a true reflection of all of the sea turtle nests each year in Florida, as it doesn’t cover every beach, but it gives a good indication of nesting trends and distribution of species.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

- Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory, 222 Clark Dr, Panacea, FL 32346 850-984-5297 Admission Fee

- Gulf World Marine Park, 15412 Front Beach Rd, Panama City, FL 32413 850-234-5271 Admission Fee

- Gulfarium Marine Adventure Park, 1010 Miracle Strip Parkway SE, Fort Walton Beach, FL 32548 850-243-9046 or 800-247-8575 Admission Fee

- Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Center, 8740 Gulf Blvd, Navarre, FL 32566 850-499-6774

To watch a female loggerhead turtle nest on the beach, please join a permitted public turtle watch. During sea turtle nesting season, The Emerald Coast CVB/Okaloosa County Tourist Development Council offers Nighttime Educational Beach Walks. The walks are part of an effort to protect the sea turtle populations along the Emerald Coast, increase ecotourism in the area and provide additional family-friendly activities. For more information or to sign up, please email ECTurtleWatch@gmail.com. An event page may also be found on the Emerald Coast CVB’s Facebook page: facebook.com/FloridasEmeraldCoast.

by Laura Tiu | Apr 14, 2017

It was disheartening to read that even with double red flags flying, 22 people had to be recused from the Gulf near Destin, FL recently, and one person lost their life. In that spirit, I believe it is important to review information on the importance of respecting our sometimes-unforgiving gulf.

First of all, stay calm.

Photo By: Laura Tiu

Swimmers getting caught in rip currents make up the majority of lifeguard rescues. These tips from Florida Sea Grant and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s National Weather Service (NWS) can help you know what to do if you encounter a rip current.

What Are Rip Currents?

Rip currents are formed when water flows away from the shore in a channeled current. They may form in a break in a sandbar near the shore, or where the current is diverted by a pier or jetty.

From the shore, you can look for these clues in the water:

- A channel of choppy water.

- A difference in water color.

- A line of foam, seaweed, or debris moving out to sea.

- A break in incoming wave patterns.

If you get caught in a rip current, don’t panic! Stay calm and do not fight the current. Escape the current by swimming across it–parallel to shore–until you are out of the current. When you get out of it, swim back to the shore at an angle away from the current. If you can’t break out of the current, float or tread water until the current weakens. Then swim back to shore at an angle away from the rip current. Rip currents are powerful enough to pull even experienced swimmers away from the shore. Do not try to swim straight back to the shore against the current.

Tips for Swimming Safely

You can swim safely this summer by keeping in mind some simple rules. Many people have harmed themselves trying to rescue rip current victims, so follow these steps to help someone stuck in a rip current. Get help from a lifeguard. If a lifeguard is not present, yell instructions to the swimmer from the shore and call 9-1-1. If you are a swimmer caught in a rip current and need help, draw attention to yourself–face the shore and call or wave for help.

Photo by: Laura Tiu

How Do I Escape a Rip Current?

- Rip currents pull people away from shore, not under the water. Rip currents are not “undertows” or “rip tides.”

- Do not overestimate your swimming abilities. Be cautious at all times.

- Never swim alone.

- Swim near a lifeguard for maximum safety.

- Obey all instructions and warnings from lifeguards and signs.

- If in doubt, don’t go out!

Adapted and excerpted from: “Rip Currents” Florida Sea Grant

The Foundation for the Gator Nation, An Equal Opportunity Institution.

by Scott Jackson | Feb 16, 2017

Northwest Florida Workshop Attendees from 2013 in Niceville, FL. This year’s workshop will be held at the UF/IFAS Extension Okaloosa County Office in Crestview, February 22, 2017. Direction and Contact Information can be found at this link http://directory.ifas.ufl.edu/Dir/searchdir?pageID=2&uid=A56

Researchers from University of West Florida recently estimated the value of Artificial Reefs to Florida’s coastal economy. Bay County artificial reefs provide 49.02 million dollars annually in personal income to local residents. Bay County ranks 8th in the state of Florida with 1,936 fishing and diving jobs. This important economic study gives updated guidance and insight for industry and government leaders. This same level of detailed insight is available for other Northwest Florida counties and counties throughout the state.

The UWF research team is one of several contributors scheduled to present at the Northwest Florida Artificial Reef Manager’s Workshop February 22. Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission and Florida Sea Grant are hosting the workshop. This meeting will bring together about fifty artificial reef managers, scientists, fishing and diving charter businesses, and others interested in artificial reefs to discuss new research, statewide initiatives and regional updates for Florida’s Northwest region. The meeting will be held at the UF/IFAS Extension Okaloosa County Office in Crestview, FL.

Cost is $15.00 and includes conference handouts, light continental breakfast with coffee, lunch, and afternoon refreshments. Register now by visiting Eventbrite or short link url https://goo.gl/VOLYkJ.

A limited number of exhibit tables/spaces will be available. For more information, please contact Laura Tiu, lgtiu@ufl.edu or 850-612-6197.

Super Reefs staged at the Panama City Marina, which were deployed in SAARS D, located 3 nautical miles south of Pier Park. Learn more about this reef project and others at the Northwest Florida Artificial Reef Manager’s Workshop in Crestview, February 22, 2017. (Photo by Scott Jackson).

Northwest Florida Artificial Reef Workshop Tentative Agenda

Date: February 22, 2017

Where: UF/IFAS Extension Okaloosa County Office, 3098 Airport Road Crestview, FL 32539

8:15 Meet and Greet

9:00 Welcome and Introductions – Laura Tiu UF/IFAS Okaloosa Co and Keith Mille, FWC

9:25 Regional and National Artificial Reef Updates – Keith Mille

9:50 Invasive Lionfish Trends, Impacts, and Potential Mitigation on Panhandle Artificial Reefs – Kristen Dahl, University of Florida

10:20 Valuing Artificial Reefs in Northwest Florida – Bill Huth, University of West Florida

11:00 County Updates – Representatives will provide a brief overview of recent activities 12:00 LUNCH (included with registration)

12:00 LUNCH

1:00 NRDA NW Florida Artificial Reef Creation and Restoration Project Update – Alex Fogg, FWC

1:15 Goliath Grouper Preferences for Artificial Reefs: An Opportunity for Citizen Science – Angela Collins, FL, Sea Grant

1:45 Current Research and Perspectives on Artificial Reefs and Fisheries – Will Patterson, University of Florida

3:00 BREAK

3:30 Association between Habitat Quantity and Quality and Exploited Reef Fishes: Implications for Retrospective Analyses and Future Survey Improvements – Sean Keenan, FWRI

3:50 Innovations in Artificial Reef Design and Use – Robert Turpin, facilitator

4:10 Using Websites and Social Media to Promote Artificial Reef Program Engagement – Bob Cox, Mexico Beach Artificial Reef Association & Scott Jackson, UF/IFAS Bay Co

4:40 Wrap Up and Next Steps – Keith Mille and Scott Jackson

5:00 Adjourn and Networking

Register now by visiting Eventbrite or short link url https://goo.gl/VOLYkJ. Live Broadcast, workshop videos, and other information will be available on Facebook at https://www.facebook.com/floridaartificialreefs/ (Florida Artificial Reefs) .

An Equal Opportunity Institution. University of Florida, Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) Extension, Nick T. Place, Dean.

by Les Harrison | Feb 4, 2017

Valentine’s Day is just a few days away and this month’s theme is evidenced by the color red. Red hearts, bows, roses (imported this time of year from South America) and candy in red boxes

This hue is not frequently seen in Wakulla County in the mist of winter’s grip, but this year azaleas bloomed in January. Still, red highlights in lawns, pastures and other open areas tend to attract attention.

Mature Column Stinkhorns are in striking contrast to most other local mushrooms. These were growing on the edge of the UF/IFAS Wakulla County Extension Demonstration Garden where wood chips are plentiful.

Photo: Les Harrison

The reason is simple. A mushroom species is taking advantage of the cool weather and available moisture.

Clathrus columnatus, the scientific name for the column stinkhorn, is a north Florida native which is common to many Gulf Coast locales. This colorful fungus has also been known by the common name “dead man’s fingers”.

The short lived above ground structure is usually two to six inches high at maturity. This area is known as the fruiting body and produces spores which are the basis for the next generation.

Two to five hollow columns or fingers project upwards above the soil or mulch. Coloration of the fruiting body can range from pink to red, and occasionally orange.

The inner surfaces of the column are covered with stinkhorn slime and spores, and which produces an especially repulsive stench. This foul odor is useful though, attracting an assortment of flies and other insects which track through it.

A small amount of the mixture of the brown slime and spores attaches to the insect’s body. It is then carried by these discerning visitors to other bug enticing spots, usually of equal or greater offensiveness to people. Spores are deposited as the slime mixture is rubbed off as the insects brush against surfaces.

Decaying woody debris is a favorable environment for the column stinkhorn to germinate. As the wood rots bacterial activity makes necessary nutrients available to this mushroom.

Other areas satisfactory for development include lawns, gardens, flower beds and disturbed soils. All contain bits and pieces of decomposing wood and bark.

Occasionally, column stinkhorns can be seen growing directly out of stumps and living trees. Presence on a living tree is a good indication the tree has serious health issues and may soon die.

This fungi starts out as a partially covered growth called a volva. The portion above and below the soils surface has the general appearance of a hen’s egg and is bright white.

The term volva is applied in the technical study of mushrooms, and used to describe a cup-like structure at the base of the fungus. It is one of the precise visible features used to identify specific species.

The cool wet weather currently in Wakulla County combined with local sandy soils and available nutrients create ideal growing conditions. While rarely notices during initial stages of growth, they are quickly spotted at or near maturity.

There are other stinkhorn mushrooms in Wakulla County, but they are not as common. In addition to North America, member of this fungi family with a fetid aroma can be found in Europe, Asia, South America and Australia.

Photo: Les Harrison

While not likely to be a Valentine’s Day gift, it still has a distinct place in the local environment. Get close and it is difficult to overlook.

To learn more about Wakulla County’s mushrooms, contact your UF/IFAS Wakulla Extension Office at 850-926-3931 or http://wakulla.ifas.ufl.edu/

by Les Harrison | Jan 8, 2017

Some of the most picturesque and scenic natural areas along north Florida’s Gulf Coast are found in Bald Point State Park. The 4,065 acre park is located on Alligator Point, where Ochlockonee Bay meets Apalachee Bay.

Easy access to water activities at Bald Point State Park.

Photo: Les Harrison

Bald Point State Park offers a variety of land and water activities. Coastal marshes, pine flatwoods, and oak thickets foster a diversity of biological communities which make the park a popular destination for birding and wildlife viewing.

These include shorebirds along the beach, warblers in the maritime oak hammocks, wading birds, and birds of prey in and around the marsh areas. The boardwalk and observation deck overlook the marsh near the beach.

During autumn bald eagles and other migrating raptors, along with monarch butterflies are frequently viewed heading south to a warmer winter.

Bald Point offers access to two Apalachee Bay beaches for water sports and leisure activities, and these facilities include a fishing dock and picnic pavilions at Sunrise beach, North End beach and Maritime Hammock beach. Grills and restrooms are also available, but pets are prohibited on the beach.

Pre-Columbian pottery helped archaeologists identify the park’s oldest site, placing the earliest human activity 4,000 years ago. These early inhabitants hunted, fished, collected clams and oysters, and lived in relatively permanent settlements provided by the abundant resources of the coast and forests.

In the mid-1800s and late 1900s, fishermen established seineyards at Bald Point. These usually primitive campsites included racks to hang, dry and repair nets. Evidence of the 19th to 20th century turpentine industry is visible on larger pine trees cut with obvious scars.

Bald Point is an excellent location for both wildlife viewing and birding.

Photo: Les Harrison

Among the varieties of saltwater fish found in the brackish tidal waterway are redfish, trout, flounder and mackerel.

Today’s visitors may fish on the bridge over tidal Chaires Creek off of Range Road, and in Tucker Lake, by canoe or kayak. Sea trout, red fish, flounder and sheepshead are common catches, and this is an excellent area to cast net for mullet or to catch blue crabs.

Bald Point State Park is open 8:00 a.m. to sunset daily, with a charge $4.00 per car with up to eight people, or $2.00 per pedestrian or bicycle

More information is available at the Florida State Park site.

There are numerous trails where the visitor and explore Florida.

Photo: Les Harrison.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 8, 2017

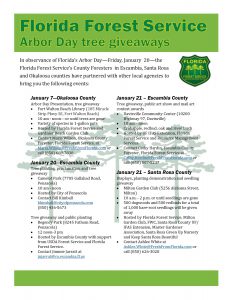

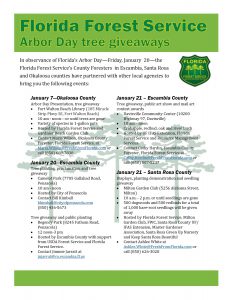

Arbor Day has a 145-year history, started in Nebraska by a nature-loving newspaper editor who recognized the many valuable services trees provide. We humans often form emotional attachments to trees, planting them at the beginning of a marriage, birth of a child, or death of a loved one, and trees have tremendous symbolic value within cultures and religions worldwide. So it only makes sense that trees have their own holiday. The first Arbor Day was such a big success that his idea quickly spread nationwide–particularly with children planting trees on school grounds. In addition to their aesthetic beauty and valuable shade in the hot summers, trees provide countless benefits: wood and paper products, nut and fruit production, wildlife habitat, stormwater uptake, soil stabilization, carbon dioxide intake, and oxygen production. If you’re curious of the actual dollar value of a tree, the handy online calculator at TreeBenefits.com can give you an approximate lifetime value of a tree in your own backyard.

Arbor Day events in the western Panhandle.

While national Arbor Day is held the last Friday in April, Arbor Day in Florida is always the third Friday of January. Due to our geographical location further south than most of the country, our primary planting season is during our relatively mild winters. Trees have the opportunity during cooler months to establish roots without the high demands of the warm growing season in spring and summer.

To commemorate Arbor Day, many local communities will host tree giveaways,plantings, and public ceremonies. In the western Panhandle, the Florida Forest Service, UF/IFAS Extension, and local municipalities have partnered for several events, listed here.

For more information on local Arbor Day events and tree giveaways in your area, contact your local Extension Office or County Forester!

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.