by Carrie Stevenson | Jul 23, 2018

Local estuaries are a beautiful place to explore with your family. Credit: Matthew Deitch, UF IFAS Extension

Florida’s rivers, springs, wetlands, and estuaries are central features to the identity of northwest Florida. They provide a wide range of services that benefit peoples’ health and well-being in our region. They create recreational opportunities for swimmers, canoers, and kayakers; support diverse wildlife for birders and plant enthusiasts; sustain a vibrant commercial and recreational fishery and shellfishery; serve as corridors for shipping and transportation; and support ecosystems that help to improve water quality. Maintaining these aquatic ecosystem services requires a low level of chemical inputs from the upstream areas that comprise their watersheds.

Aquatic ecosystems are especially sensitive to nitrogen and phosphorus, which are key nutrients for the growth of plants, algae, and bacteria that live in these waters. High levels of these nutrients combined with our sunny weather and warm summer temperatures create conditions that can lead to rapid growth of aquatic plants and algae, which can cover these water bodies and make them no longer enjoyable for people and wildlife. It can also cause dissolved oxygen levels to fall, as plants respire (especially at night, when they are not photosynthesizing) and as bacteria consume oxygen to break down dead plant material. Low dissolved oxygen can create conditions that are deadly for fish and shellfish.

The Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) lists more than 1,400 water bodies (including rivers, springs, wetlands, and estuaries) as impaired by pollutants. Many of these are impaired by excessive nitrogen or phosphorus. It is a daunting challenge to reduce pollutants in these water bodies because their inputs frequently come from all over the landscape, rather than a specific point—nutrients can come from agricultural fields, residential landscapes, septic tanks, atmospheric deposition, and livestock throughout the watershed.

In Florida, FDEP has begun a program to reduce nutrient concentrations in impaired watersheds by collaborating with landowners and other stakeholders to develop management programs to reduce pollutants entering the state’s waters. This pollutant reduction program is currently focused on Florida’s spring systems, including Jackson Blue Spring and Merritt’s Mill Pond in Jackson County. Merritt’s Mill Pond is a 4-mile long, 270-acre pond located near Marianna, and it is a popular regional destination for swimming, boating, kayaking, and fishing in the Panhandle. Its main source is Jackson Blue Spring, which produces, on average, more than 70 million gallons of water each day. Excessive growth of aquatic plants and algae in the pond during summer reduces the area available for swimming and boating. In 2014, FDEP began working with agricultural producers, residents, developers, local government officials, and other stakeholders to identify nutrient contributions in the Merritt’s Mill Pond watershed and develop an action plan to reduce nutrients entering the pond in the coming decades. Collaborations with stakeholders help to improve the accuracy of pollutant estimates, and to ensure the plan is designed appropriately to achieve desired ecological outcomes.

This Action Plan for reducing nutrients into Merritt’s Mill Pond provides an opportunity for land managers to implement their own plans to reduce nutrient contributions without FDEP imposing rigid regulations or mandating particular actions. People can choose from an array of Best Management Practices designed to reduce nutrient contributions, and the state has made funds available for people to help implement these plans. Implementing this Action Plan will restore the wonders of Merritt’s Mill through the 21st Century.

This article was written by: Matthew J Deitch, PhD, Assistant Professor, Watershed Management with the UF IFAS Soil and Water Sciences Department at the West Florida Research and Education Center. For more information, you can contact him at mdeitch@ufl.edu or 850-377-2592.

by Judy Biss | Mar 18, 2018

Adult grass carp, Ctenopharyngodon idella Val. Credit: Jeffrey E. Hill, University of Florida

Spring is only days away. Everywhere you look, plants of all kinds are awakening to recent rains, longer days, and fertile soils; and this includes aquatic plants as well! Florida has hundreds of aquatic plant species, and they are an often-overlooked feature of Florida’s landscape. Overlooked that is, until the growth of non-native (or even some native) species interferes with use of our waters. Some aquatic plant species can become problematic in Florida waters as their growth interferes with fishing, flood control, navigation, recreation, livestock watering, or irrigation. For these reasons, being knowledgeable about properly managing aquatic plants is important to the many uses of Florida’s waters, whether it be a state managed public waterbody, or your own backyard farm pond.

Any pest, whether plant, animal, or insect, is best managed using “IPM” or Integrated Pest Management. IPM involves using a variety of available management “tools” to control pests in an economically and environmentally sound manner. As in any IPM effort, the first thing to do is identify what is causing the problem. Next, define what your management goals are. Then, research what tools are available for you to manage the problem. And finally, devise and implement your management plan.

In this article, we will look at one of the IPM “tools” used to manage aquatic plants – the grass carp (Ctenopharyngodon idella Val.). The use of grass carp to manage problematic levels of aquatic plants falls under the general management term of “biological control.” Biological control essentially uses one living organism to control another living organism. Grass carp have become one of the most widely recognized examples of biological control.

The Grass Carp

As the name implies, the grass carp is an herbivorous fish that eats plants. It is native to eastern Russia and China living in large muddy rivers and associated lakes, and is actually one of the largest members of the minnow family. According to the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission the largest triploid grass carp taken in Florida was 15 years old, 56″ long and weighed 75 pounds! The grass carp has been introduced into more than 50 countries and is used as a food item in many places around the world. They are used in nearly all states of the USA to manage aquatic plants.

Introduction into the United States:

“The grass carp was considered for introduction into the U.S. primarily because of its plant-eating diet, which was thought to have great potential for the control of aquatic weeds. In 1963 the U.S. Bureau of Sport Fisheries and Wildlife Fish Farming Experiment Station, Stuttgart, Arkansas, in cooperation with Auburn University, imported grass carp for experimental purposes; in 1970, this fish was introduced into Florida primarily for researchers to study its ability to control hydrilla.” (Grass Carp: A Fish for Biological Management of Hydrilla and Other Aquatic Weeds in Florida). “Early release of diploid fish led to reproductive populations in several US drainage systems, including the Mississippi River and major tributaries” (Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae))

Development of the Sterile Triploid

According to the UF/IFAS publication, Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae), “Use of the fish was limited from 1970 until 1984 due to tight regulations surrounding concerns of escape and reproduction, and the potential impacts that colonization of the fish could have on native flora and fauna. These concerns led to research that developed a non-reproductive fish, which was equally effective in controlling hydrilla.” This non-reproductive fish is known as the triploid grass carp. Through a process of subjecting fertilized grass carp eggs to heat, cold, or pressure, the resulting fish have an extra set of chromosomes rendering the fish sterile. Triploid carp have the same herbivorous characteristics as the normal diploid carp, but they are unable to spawn and reproduce. Their inability to reproduce is what makes them a viable tool to manage aquatic plants, and that is because their numbers and feeding pressure can be controlled, they cannot overpopulate a waterbody, nor if they escape, will they overpopulate un-managed areas.

The growth of invasive non-native (or even some native) aquatic plant species can interfere with the many uses of Florida’s waters. This is invasive hydrilla mixed with water lilies in a Florida lake. Photo by Judy Biss

What kinds of aquatic plants do they eat?

The grass carp grazes on many types of aquatic plants, but it does have its preferences. Its most preferred aquatics plants are hydrilla, chara (musk grass), pondweed, southern naiad, and Brazilian elodea. Its least favorite aquatic plants are species such as water lily, sedges, cattails, and filamentous algae. It will, however, graze on many types of plants even shoreline or overhanging vegetation in the absence of its preferred foods. Another reason the grass carp is an effective plant management tool is because it eats many times its body weight in plant material. As stated in Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae), “every 1 lb. increase in fish weight requires 5–6 lbs. of dry hydrilla (Sutton et al. 2012), which—considering hydrilla is 95% water—is a great deal of live plant material.”

Use of Grass Carp as a Biological Control:

Integrating the use of grass carp in aquatic plant management plans is usually cost effective. In many cases involving the use of grass carp, overabundant aquatic weed infestations are first treated with an aquatic herbicide to reduce biomass. The carp are then stocked to control regrowth and to extend the time between herbicide treatments. This can be up to 5 or more years, depending on the situation. One factor in long term control is the survival of the stocked grass carp. They are not without predators as largemouth bass, otters, birds, etc. readily prey on small grass carp. Stocked fish should be at least 12 inches long to help avoid predation and provide plant control. Other considerations to factor into your management plans are the long term, yet non-specific, control that grass carp can provide. If not stocked in the correct manner, they may end up eating aquatic plants that you wish to maintain. Also, if they eat all the aquatic plants, your once clear water may become dominated by algae instead.

How can I get grass carp for my lake or pond?

The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC) administers the Grass Carp program for Florida. A permit is required before you can purchase carp, and only the sterile triploid carp are permitted for use in Florida. The FWC can answer many questions about the use of grass carp and if this aquatic plant management “tool” is the right one for you to use in your particular situation. In north Florida, the regional FWC office is located at 3911 Highway 2321 Panama City, FL 32409, Phone: 850-767-3638.

What do I need to know about triploid grass carp?

Cost: Triploid grass carp cost between $5 and $15 each and are usually stocked at three to ten fish per acre, resulting in costs as low as $15 per acre. In comparison, herbicides cost between $100 and $500 per acre and mechanical control may cost more than twice that.

Time: Grass carp usually take six months to a year to be effective in reducing problem vegetation, although they provide much longer term control than other methods, often up to five years before restocking is necessary. When used in conjunction with an initial herbicide treatment, control of problem vegetation can be achieved quickly, and fewer carp are required to maintain the desired level of vegetation.

Overstocking: Once stocked in a lake or pond, carp are very difficult to remove. If overstocking occurs, it may be ten years or more before the vegetation community recovers. Even after carp are removed, other herbivores such as turtles may prevent the regrowth of vegetation.

Water Clarity: Aquatic plants remove nutrients in the water. When plants are removed, nutrients may then be utilized by phytoplankton, turning the water green. Clarity may be improved by reducing or eliminating sources of nutrients into the lake such as road runoff and lawn fertilizer.

Inflows/Outflows: It is in the best interest of people stocking carp to keep them in the desired lake or pond. It is also a required condition of the permit. Any inflows or outflows through which carp could escape into other waters require barriers to prevent fish from escaping into waters not permitted.

For more information on this topic, please see the following resources used for this article:

Aquatic and Wetland Plants in Florida

Plant Management in Florida Waters

Grass Carp, the White Amur: Ctenopharyngodon idella Cuvier and Valenciennes (Actinopterygii: Cyprinidae: Squaliobarbinae),

Grass Carp: A Fish for Biological Management of Hydrilla and Other Aquatic Weeds in Florida).

Chinese Grass Carp

FWC Triploid Grass Carp Permit

UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants – Aquatic Plant Control Methods

by zadwiggins | Jul 29, 2017

Bacopa caroliniana, also known as lemon bacopa, is a popular aquatic plant. It is mostly found in the southeastern United States in states such as Florida, Alabama, Georgia, South Carolina, Mississippi and even Texas. Lemon bacopa has a perennial life cycle that could make it a weed to some, or desired plant to others. Also, it can be found as a submergent plant or an emergent one.

Lemon bacopa

Photo: UF

It tends to grow near shorelines and sometimes in water that is less than 3 inches deep. Lemon bacopa has a single stem with opposite leaf growth. The leaves are thick and juicy. The reason some people enjoy and even encourage planting this plant is the pretty, attractive, purple-blue flower that sprouts. They are a popular plant used to add beauty to water gardens and to provide habitat in wetland enhancement as well as restoration projects. However, this plant can be easily propagated which could lead to it becoming weedy if not paid attention to carefully. Lemon bacopa roots easily from cuttings, so whether if it is purposely cut or by natural causes, it can easily spread and take over a water garden.

This species is very adapted and common throughout Florida. Although lemon bacopa can be weedy in some situations, it is most often considered a beneficial native plant that brings a number of desirable characteristics to almost any aquatic setting.

Source: UF IFAS EDIS publications

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 14, 2017

Article by Gadsden County Extension Agent

DJ Zadarreyal

Vallisneria americana, also known as tape grass or eel grass, is a common native aquatic weed in the state of Florida. Tape grass has tall, grass-like leaves that are a light green in coloration and rise vertically from the crown to the top of the water. Once the leaves reach the top of the water, they casually float along the surface.

Common tape grass Vallisneria americana.

Photo: UF IFAS

The technique of propagation is by runners. These runners grow out from the crown along the sand and new plants arise from the end of them. There are separate male and female plants, although they grow on the same plant. The female flowers are on lengthy stems, which reach to the surface. However, the male flowers are loosely attached at the base of the leaves. When released, the male flowers float to the surface where they move alongside the female flowers to fertilize them.

A good way to distinguish tape grass from other weeds is to observe the leaves and the tips. Tape grass have round leaf tips while many other weeds have pointed leaf tips. In addition, tape grass is a submerged weed that possesses long, ribbon like leaves.

There are several uses for tape grass. Restoration of the pond floor is a useful purpose. One of the benefits of tape grass is that they are great oxygenators. Tape grass is also a common home based aquarium plant. They provide an eye-catching scene that fish and humans enjoy.

Source:

Guide of Tropical Fish, Everything You Need to Know About Tropical Fish

by Judy Biss | Mar 17, 2017

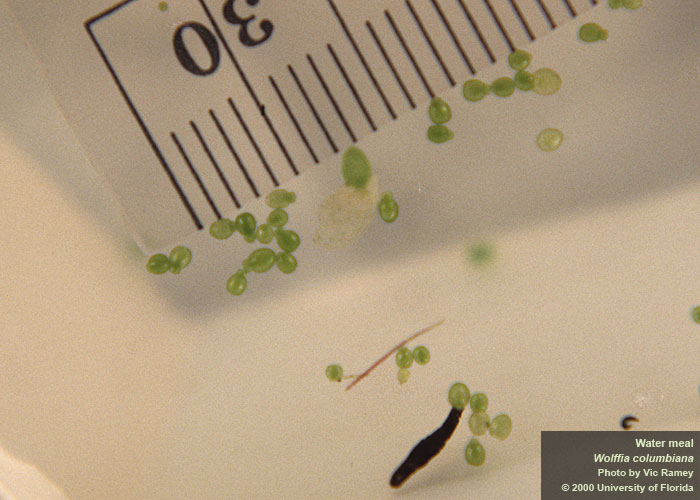

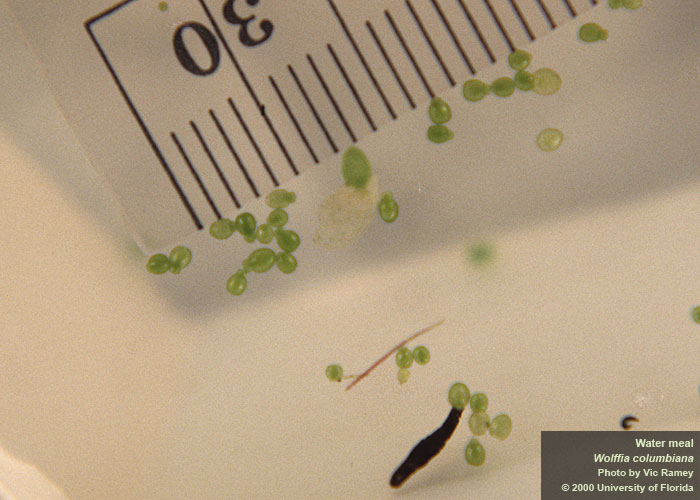

Water meal, the world’s smallest flowering plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Some of the world’s smallest flowering plants grow in aquatic environments. And a number of these tiny aquatic plants grow natively right here in Florida! Aquatic plants of all kinds display an amazing array of adaptations for growing in water. They can tolerate drought, flood, flowing water, stagnant water, cold spring runs, and warm brackish marshes. They grow in sun and shade and nutrient rich to nutrient poor waters. Some of their adaptations include the ways in which they grow such as being rooted in bottom sediments, submerged, emerged, leaves floating on the surface, or completely free floating with their roots dangling into the water below.

The tiniest of aquatic plants are in this group of free floating plants. Let’s take a look at five of these tiny (less than ½ inch wide) plant species in Florida. They are most noticeable in slow moving waters, ponds, or coves protected from wind where many thousands of them form floating mats almost like paint on the water surface. Even though individual plants are small, some of these plant species are used by wildlife and invertebrates for food and cover. Oftentimes, especially in small ponds, these tiny floating plants can cover the entire water surface resulting in the need for management, especially if the ponds are used for irrigation or livestock watering.

In this article we will look at the native species, but as you are probably aware, there are also non-native representatives of these tiny plants established in our waters, but that is a story for another time…

The images and text below are from the UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Species website, list of Plants Sorted by Common Name.

Watermeal

“Water meal, native to Florida, is a tiny, floating, rootless plant. At 1 to 1.5 mm long, it is the smallest flowering plant on earth. It is occasionally found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs of the peninsula and central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003).”

Water meal has a grainy feel and can be used as one clue in identifying this plant. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

American Waterfern

“There are six species of Azolla in the world. American waterfern is the species commonly found in Florida. American waterfern is a small, free-floating fern, about one-half inch in size. It is most often found in still or sluggish waters. Young plants are, at first, a bright or grey-green. Azolla plants often turn red in color. American waterfern can quickly form large, floating mats.”

A large area of waterfern showing the reddish coloration. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Close up of individual water fern plants. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Giant Duckweed

“Giant duckweed is a native floating plant in Florida. Though very small, it is the largest of the duckweeds…..frequently found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs from the peninsula west to the central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003)… Giant duckweed has two to three rounded leaves, which are usually connected. Giant duckweeds usually have several roots (up to nine) hanging beneath each leaf. The underleaf surface of giant duckweed is dark red.”

Close up of individual duckweed plants showing roots hanging freely below the plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

A typical scene of duckweed in a quiet cove or pond. Photo by Ann Murray, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

Small Duckweed

“Small duckweeds are floating plants. They are commonly found in still or sluggish waters. They often form large floating mats…. Small duckweeds are tiny (1/16 to 1/8 inch) green plants with shoe-shaped leaves. Each plant has two to several leaves joined at the base. A single root hangs beneath.”

This is small duckweed, note the single root below each plant. Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

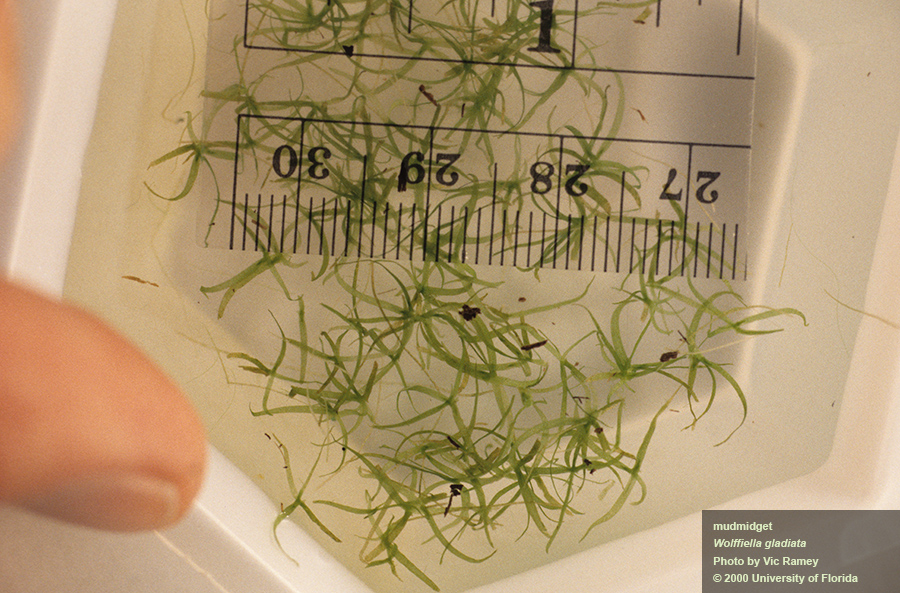

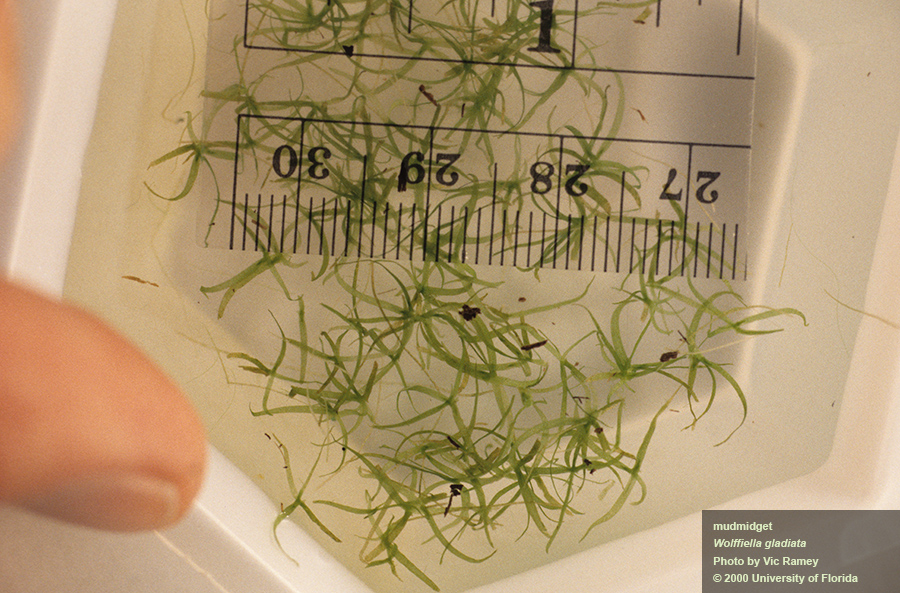

Mudmidget

“Mud-midget, native to Florida, is another small duckweed, but this one has narrow, elongated fronds. The fronds are usually connected to form starlike colonies. The fronds are 5-10 mm long; the flowers are extremely small and difficult to see. Mud-midget plants float just beneath the surface of the water and is frequently found growing in rivers, ponds, lakes, and sloughs from the peninsula west to the central panhandle of Florida (Wunderlin, 2003)….”

Mudmidget, Photo by Vic Ramey, University of Florida/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants. Used with permission.

If you have any questions about aquatic plant identification or management options, please contact your local UF/IFAS Extension County office. And, for more information on Florida’s aquatic plants, please see the following resources used for this article:

UF/IFAS Center for Aquatic and Invasive Species

Plants Sorted by Common Name

USDA Forest Service – Duckweed

USDA Forest Service – Water Fern

Native Aquatic and Wetland Plant Fact Sheets

Aquatic Plant Identification List with Pictures and Videos

by hollyober | Dec 16, 2016

Christmas trees can provide benefits to wildlife long after they have served as holiday decoration indoors. Credits: IFAS photo database.

Americans purchased approximately 30 million live Christmas trees last year. If you plan to have a live tree this winter, and you’re wondering what you could do with your tree once it has finished its role as holiday decoration in your home, read below. Rather than simply dragging your tree to the curb for the waste disposal truck to pick up, you could prolong the life of your holiday tree by repurposing it to benefit wildlife.

YOUR TREE COULD PROVIDE FOOD FOR WILDLIFE

Many of the needles may have dropped from your Christmas tree as it dried out while indoors, but the branches should still be intact. This means your tree could be used as a frame to present food for wildlife. After removing your indoor decorations, consider propping the tree up in your yard (perhaps using the same stand you used indoors), and adorning the branches with food enjoyed by wildlife visitors. Some low-budget options include mesh bags filled with bird seed (black oil sunflower seed, safflower seed, and thistle (nyjer) are favorites of many common backyard birds), pine cones smeared with peanut butter, home-made suet cakes, and strings of fruit such as apple slices, orange slices, or grapes. If you choose this option, beware that you may attract not only birds, but mammals such as squirrels, raccoons, opossums, and others.

If you’d like to watch your wildlife visitors, be sure to attach the food items with string so that the animals must eat the food at the site of the tree rather than carrying it away to eat or store elsewhere out of view. Consider using a biodegradable string (i.e., cotton) to secure the food items to your tree so you can eventually compost the tree without worrying about needing to remove the string.

YOUR TREE COULD PROVIDE SHELTER FOR WILDLIFE

If you’re tired of seeing your holiday tree in its upright position, consider taking it outdoors, laying it down, and heaping other vegetative debris loosely on top to form a ‘brush pile’. Brush piles are mounds of woody vegetation created specifically to provide shelter for wildlife.

The lower portions of a brush pile can offer cool, shaded conditions that allow small mammals such as rabbits to hide from the weather and from predators. Meanwhile, the upper portions can serve as perch sites for songbirds. The entire pile may be used as resting sites for amphibians and reptiles. In yards with few understory trees or shrubs, and at times of year when many trees and shrubs have limited foliage, these brush piles can provide much-appreciated cover for many kinds of wildlife.

YOUR TREE COULD PROVIDE SHELTER FOR FISH

Your retired Christmas tree could be used to make long-lasting habitat improvements for fish. In artificial ponds with little submerged vegetation, the addition of one or more Christmas trees could upgrade the quality of refuge and feeding areas for fish. Small fishes may hide among purposely submerged Christmas trees for protection, and larger fishes may follow them. If you’ve got an artificial pond on your property, consider adding discarded trees to create a place where fish can hide and find food, and also to concentrate fish for angling. Simply secure a cinder block to your holiday tree using heavy wire or thin cable and place it far enough from shore that water covers the top of the tree by a couple of feet. When constantly submerged, Christmas trees can persist for many years underwater.

Not only can your tree offer enjoyment to you when decorated with lights and ornaments indoors, but it can also allow you to provide post-holiday gifts to the wildlife and fish on your property.