by Laura Tiu | May 3, 2019

There are five species of sea turtles that nest from May through August on Florida beaches, with hatching stretching out until October. The loggerhead, the green turtle, and the leatherback all nest regularly in the Panhandle, with the loggerhead being the most frequent visitor. Two other species, the hawksbill and Kemp’s Ridley nest infrequently. All five species are listed as either threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act. Due to their threatened and endangered status, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission/Fish and Wildlife Research Institute monitors sea turtle nesting activity on an annual basis.

A group checks out a recently hatched sea turtle nest on the dunes in south Walton county in Florida.

Annual total nest counts for loggerhead sea turtles on Florida’s index beaches fluctuate widely and scientists do not yet understand fully what drives these changes. From 2011 to 2018, an average of 106,625 sea turtle nests (all species combined) were recorded annually on these monitored beaches. In 2018, there was a slight decrease in nests with only 96,945 nests recorded statewide. This is not a true reflection of all of the sea turtle nests each year in Florida, as it doesn’t cover every beach, but it gives a good indication of nesting trends and distribution of species.

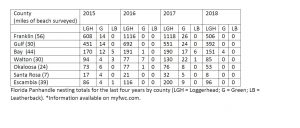

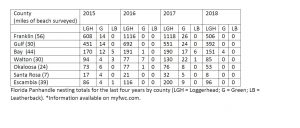

2015-2018 Florida Panhandle turtle nesting totals for all species.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

- Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory

222 Clark Dr

Panacea, FL 32346

850-984-5297

Admission Fee

- Gulf World Marine Park

15412 Front Beach Rd

Panama City, FL 32413

850-234-5271

Admission Fee

- Gulfarium Marine Adventure Park

1010 Miracle Strip Parkway SE

Fort Walton Beach, FL 32548

850-243-9046 or 800-247-8575

Admission Fee

- Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Center

8740 Gulf Blvd

Navarre, FL 32566

850-499-6774

The Foundation for The Gator Nation. An Equal Opportunity Institution

by Rick O'Connor | Feb 2, 2018

Man what a winter!

Between multiple days below freezing, tough traveling, and the flu it has been a brutal winter season so far.

Dead Kemps Ridley Sea Turtle washed ashore in Little Sabine near Pensacola Beach. This turtle died of ingesting monofilament fishing line.

Photo: Betsy Walker

It is not that different for some of our marine wildlife friends. The low temperatures have driven marine water temperatures down as well, particularly in the shallow areas. There have been many reports of cold stunned sea turtles up and down the Florida panhandle – over 900 of them. There have been reports of cold stunned iguanas falling from trees and the loss of pythons in south Florida. The question sometimes comes up – “how do they deal with this apparent return from the dead?”

One has to remember we are dealing with reptiles – cold-blooded creatures. Actually, the more correct term is poikilothermic. It really does not pertain to the temperature of their blood but their core body temperature in general. Some animals, like humans, can maintain a constant body temperature, like 98.6°F, no matter what the environmental temperatures are – these are referred to as homotherms. Heterotherms can allow their body temperatures fluctuate within a range – but are in control of their body temperatures. The poikilotherms cannot control their body temperature and are thus at the mercy of the environment – the classic “cold blood”. Some of these poikilotherms have been known to actually freeze and thaw – with no observable problems, not so much for our “warm blooded” friends.

So what’s up with the cold-stunned situation?

Well… even with the “cold bloods”, extreme temperature changes can be very stressful. Some respond by changing their behavior, others their physiology, others both. They will alter their feeding – basically stop. In some, the pH and ion balance within their blood becomes unbalanced, which can trigger the feeding reduction response and increase ion exchange within the lungs. The partial pressure within the venous blood can decrease and this, along with the chemical imbalance and feeding reduction, can trigger a “lethargic” response and even a “floating” response in the marine turtles.

Locally, it seems to be the sea turtles who are having the most problems. In south Florida, scientists have noticed the American Crocodile and the invasive pythons struggle with these cold temperatures but the wider ranged American Alligator and numerous species of native snakes do not. The “locals” seem to alter their behavior to adjust for these extreme temperature drops – a method that the tropical species are not practicing. It is known that certain native freshwater turtles over winter in frozen ponds, and diamondback terrapins are known to “hunker down” in muddy bottoms of salt marsh creeks when water temperatures drop below 59°F.

With sea turtles, the larger migratory individuals offshore are still moving at 43°F but is the smaller inshore juveniles that are the subject of stunning events. The water temperatures change more rapidly in shallower water and at 43°F, these smaller sea turtles become lethargic and float – which increases their chance of predation. Data suggest that Green Sea Turtles begin to slow activity and Kemps Ridleys become more agitated when water temperatures drop below 68°F, both become dormant, reduce feeding and breathing when they drop below 59°F. It is believed the real problems from being cold stunned are from the reduction of food as much, if not more than, the actual temperature itself. The “cold bloods” bask to increase their body temperatures so that they can actually digest their food.

It is a problem frequently encountered along the American east coast but not as much in Florida. However, this year has been different. The staff and volunteers from government agencies and local aquaria have done a champion job rescuing and rehabilitating many of these animals.

References

Mazzotti, F. J., M. S. Cherkiss, M. Parry, J. Beauchamp, M. Rochford, B. Smith, K. Hart, and L. A. Brandt. 2016. Large reptiles and cold temperatures: do extreme cold spells set distributional limits for tropical reptiles in Florida? Ecosphere 7(8):e01439. 10.1002/ecs2.1439

Moon D.Y., D.S. MacKenzie, D.W. Owens. 1997. Simulated Hibernation of Sea Turtles in the Laboratory: I. Feeding, Breathing Frequency, Blood PH, and Blood Gases. The Journal of Experimental Zoology. 278: pp. 362-380.

Milton, S.A., P.L. Lutz. 2003. The Biology of Sea Turtles, Volume II. Edited P.L. Lutz, J.A. Musick, J. Wyneken. CRC Press. Pp. 510.

by Laura Tiu | Jun 3, 2017

There are five species of sea turtles that nest from May through October on Florida beaches. The loggerhead, the green turtle and the leatherback all nest regularly in the Panhandle, with the loggerhead being the most frequent visitor. Two other species, the hawksbill and Kemp’s Ridley nest infrequently. All five species are listed as either threatened or endangered under the Endangered Species Act.

Due to their threatened and endangered status, the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission/Fish and Wildlife Research Institute monitors sea turtle nesting activity on an annual basis. They conduct surveys using a network of permit holders specially trained to collect this type of information. Managers then use the results to identify important nesting sites, provide enhanced protection and minimize the impacts of human activities.

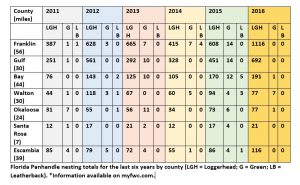

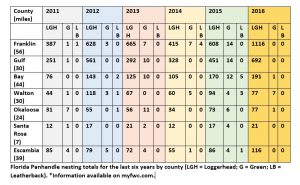

Statewide, approximately 215 beaches are surveyed annually, representing about 825 miles. From 2011 to 2015, an average of 106,625 sea turtle nests (all species combined) were recorded annually on these monitored beaches. This is not a true reflection of all of the sea turtle nests each year in Florida, as it doesn’t cover every beach, but it gives a good indication of nesting trends and distribution of species.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

If you want to see a sea turtle in the Florida Panhandle, please visit one of the state-permitted captive sea turtle facilities listed below, admission fees may be charged. Please call the number listed for more information.

- Gulf Specimen Marine Laboratory, 222 Clark Dr, Panacea, FL 32346 850-984-5297 Admission Fee

- Gulf World Marine Park, 15412 Front Beach Rd, Panama City, FL 32413 850-234-5271 Admission Fee

- Gulfarium Marine Adventure Park, 1010 Miracle Strip Parkway SE, Fort Walton Beach, FL 32548 850-243-9046 or 800-247-8575 Admission Fee

- Navarre Beach Sea Turtle Center, 8740 Gulf Blvd, Navarre, FL 32566 850-499-6774

To watch a female loggerhead turtle nest on the beach, please join a permitted public turtle watch. During sea turtle nesting season, The Emerald Coast CVB/Okaloosa County Tourist Development Council offers Nighttime Educational Beach Walks. The walks are part of an effort to protect the sea turtle populations along the Emerald Coast, increase ecotourism in the area and provide additional family-friendly activities. For more information or to sign up, please email ECTurtleWatch@gmail.com. An event page may also be found on the Emerald Coast CVB’s Facebook page: facebook.com/FloridasEmeraldCoast.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 4, 2016

October 31st not only reminds all that the ghost and goblins are out and about, but that the sea turtle nesting season is complete for another year. These federally protected animals typically begin nesting in late April and continue into the month of October – but there is almost always someone late to the party…

Young loggerhead sea turtle heading for the Gulf of Mexico. Photo: Molly O’Connor

What is neat about sea turtles is that their nesting beaches are usually always in the same general vicinity – meaning Pensacola Beach turtles are Pensacola Beach turtles… each year – and it is always great to see them come back. And this year, come back they did…

I have data collected by Gulf Islands National Seashore going back to 1996. The number of hatching nests on Escambia County beaches has ranged from a low of 8 (2005) to 52 in (2011); it has averaged around 25 hatching nests each year. This year was different…

This year, within the National Seashore, we had a total of 68 nests in Escambia County, 56 of which were on Santa Rosa Island. This is great news!

59 of the 68 nests hatched (87%) – which is also great news – typically only 10-20% of diamond back terrapin nests avoid predators. Most of the sea turtle nests lost this year were due to flooding from tropical storms in the Gulf. There was one nest between Pensacola Beach and Navarre Beach that was raided by a coyote and I am sure there were depredated nests all along the panhandle. But again, between 75-90% of terrapin nests are lost to raccoons, so the sea turtles had a good year. A recent report from southwest Florida states the same – a record nesting season for the Gulf coast.

However, there is still one problem lurking out there… disorientation…

Disorientation occurs when these successful hatchlings emerge from the sand and head the wrong way – typically towards artificial lights. Sea turtles are attracted to shortwave light (blues, greens, and white). Much of our artificial lighting falls into those wavelengths – and attract hatchlings. Since 1996 between 30 – 89% of Escambia County nests have shown signs of disorientation; the average is 49%. This year 63% of the Escambia County nests showed disorientation behavior. We are lucky that we have dedicated turtle watch volunteers to step in and correct these – but they cannot be there for all hatchings – we really need to alter our lighting. Longer wavelengths (yellow and red) do not attract most hatchlings, and therefore – are considered “turtle friendly”. Switching our outdoor lighting to these colors, reducing the illumination, lowering the elevation of the lighting, and shielding the light to direct it towards the ground all help reduce the disorientation problem.

Most panhandle counties have some form of coastal lighting ordinance to address this problem and problems with other wildlife. Ordinances vary some from county to county but the basics are the same; keep it long, keep it low, keep it shielded. Keep it long refers to the wavelength – usually less than 560nm (in the yellow/red portion of the spectrum). Keep low refers the height of the light fixture. If it can be placed at a lower height this is preferred, if not shielding the light source to direct down is required. We must also remember indoor lighting. This can be reduced by simply closing the curtains, moving lamps away from windows, or using tinted windows (if you are replacing yours). Who has to be wildlife friendly varies from county to county, so property owners should contact their Sea Grant Extension Agents if they have questions. There are funds available to help some complete this process and this to varies from county to county.

It’s been a great nesting season, let’s make it even better by reducing the amount of disoriented hatchlings.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 26, 2016

It is August, we are just off another successful Sea Turtle Baby Shower event in the Pensacola area, and we are in peak season for sea turtle hatching. Those little guys have a tough road to follow trying to emerge from their nest to reach the open waters of the Gulf of Mexico. Within the nest the young wait for cooler temperatures and no vibrations to begin their climb towards the surface. Once they have emerged, they locate the shortwave light of the moon and stars reflecting off of the water and head for sea. However, ghost crabs, fox, and coyotes, all excavate nests and consume hatchlings running across the sand.

This sea turtle frequents the nearshore snorkel reef at Park East in Escambia County.

Photo: Robert Turpin

But these predators are not alone on Pensacola Beach. Humans have moved onto the island in large numbers. Vehicle tracks, large holes, tents, chairs, and our pets all are obstacles for the young in their journey to the sea. One of the larger problem has been lighting. Most of our buildings are well lit for safety. We tend to use shortwave lighting systems that produce bright white lights similar to what the moon and stars reflect off of the Gulf – many times brighter. Because of this many of the hatchlings will disorient and travel towards the buildings and roads instead of the open Gulf… this certainly is not good. Disoriented turtles will wonder onto road ways where they are hit by cars, and under or around buildings where they can become lost or come in contact with house pets and rats – not to mention the increase time on land will increase the chance of a native predator finding them. If they make it until morning, there is the problem of shorebirds and the sun – the chances of the hatchlings surviving a disorientation are not good.

There are a variety of reasons why sea turtle populations are low enough to have them listed, but this is certain one of the larger problems. Data from Escambia County extending back to 1996 show that, on average, 48% of the sea turtle nests disorient – and it has been as high as 70%.

So What Can We Do to Help the 2017 hatchlings?

First, we are having a big year for nesting. Mark Nicholas, GINS and permit holder for sea turtle work here, indicated there were 101 nests in our area this year… we have a chance to have a really big and successful sea turtle nesting season – with a little help from you.

- Clean the beach before you head in for the night. Most panhandle counties actually have a “Leave No Trace” ordinance which requires the removal of chairs, tents, etc. – but be sure the holes are filled in and the trash is removed as well.

- For inside lighting – turn down the lights and/or close the currents. Exterior lighting should be “turtle friendly” – meaning long wavelength – which means yellow/red. Most panhandle counties have an ordinance for exterior lighting. In Escambia County residents have until 2018 to comply – but we encourage you to make those changes as soon as you can to help the turtles hatching this season. “Turtle Friendly” would include the big three – KEEP IT LOW, KEEP IT LONG, AND KEEP IT SHIELDED. Keep it low meaning as low to the ground as you can. If that is not possible, place a shield on the fixture to direct the light down to where you are walking and not out to the beach. Keep it long refers to the wavelength, longer than 560 nanometers, which is in the yellow/red range of color. Studies show that hatchlings are attracted to the shortwaves (white/blue) end of the spectrum. Having long wave lighting will increase the chances of the hatchling finding the shortwaves from stars off of the Gulf. You will want to keep the illumination down as well. We recommend 25W bulbs, which is bright enough to see and reduces the chance of attracting a young turtle.

- Keep a distance from the marked nests – remember that vibrations (even from your walking) can cause the hatchlings to wait – and waiting too long can cost them their lives. If you are lucky enough to see baby turtles crawling for the Gulf – do not use flash photography and do not use flash lights – unless they have a protective red film producing a low intensity red light.

- If you find a group of hatchlings that are obviously disoriented, contact the local authority in your area. In Escambia County we recommend calling the sheriff substation on the island or the Gulf Breeze dispatch – who will contact the National Park.

If you have questions about turtle lighting options, the current county ordinances designed to help island wildlife, or the Turtle Friendly Beaches program, contact your County Extension Sea Grant Agent.

Many counties in the panhandle have lighting and barrier ordinances to protect wildlife and workers.

Photo: Rick O’Connor