by Andrea Albertin | Oct 9, 2020

Special care needs to be taken with your septic system after flooding. Image: B. White NASA. Public Domain

During and after floods or heavy rains, the soil in your septic system drainfield can become waterlogged. For your septic system to treat wastewater, water needs to drain freely in the drainfield. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system under flood conditions.

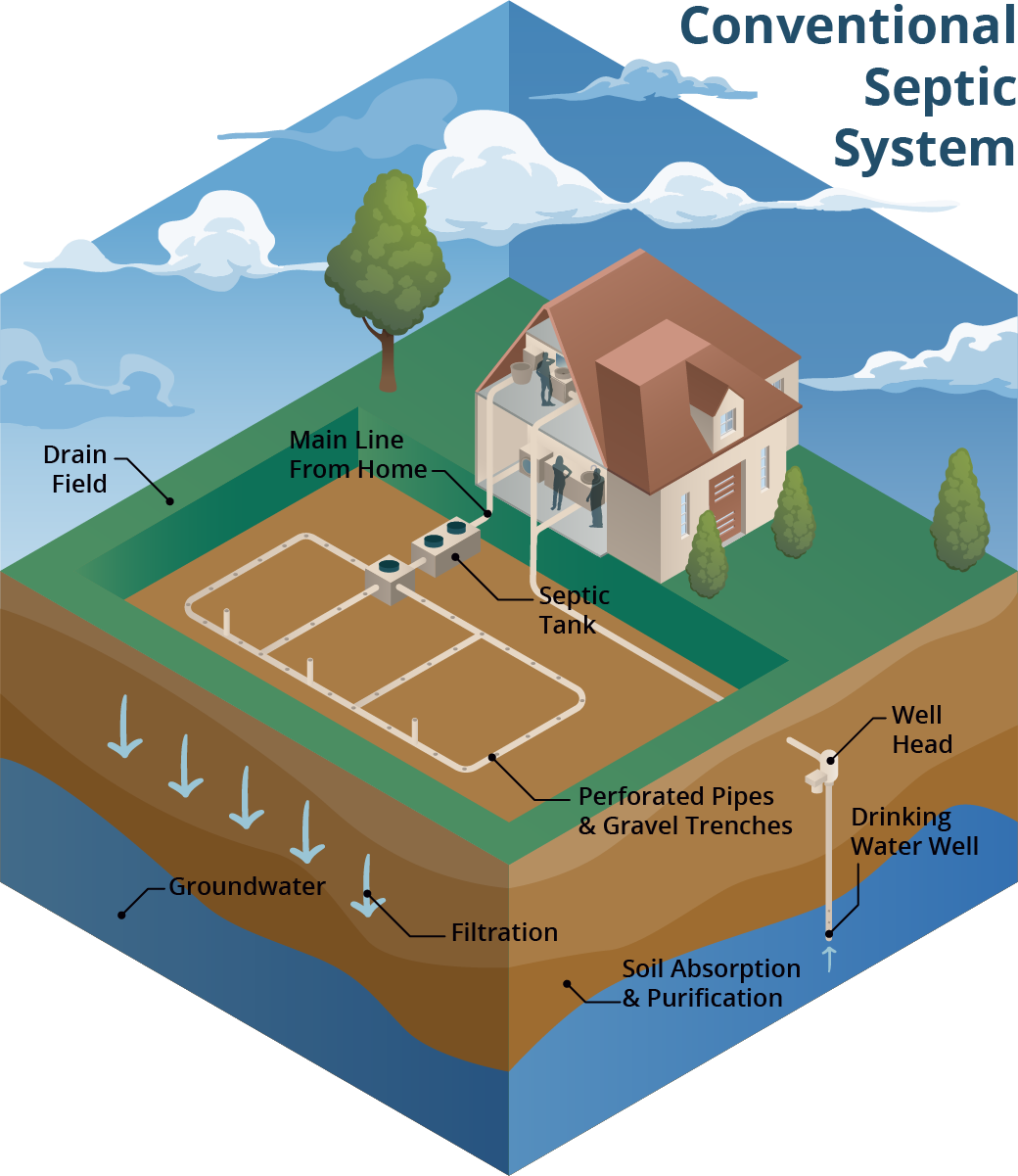

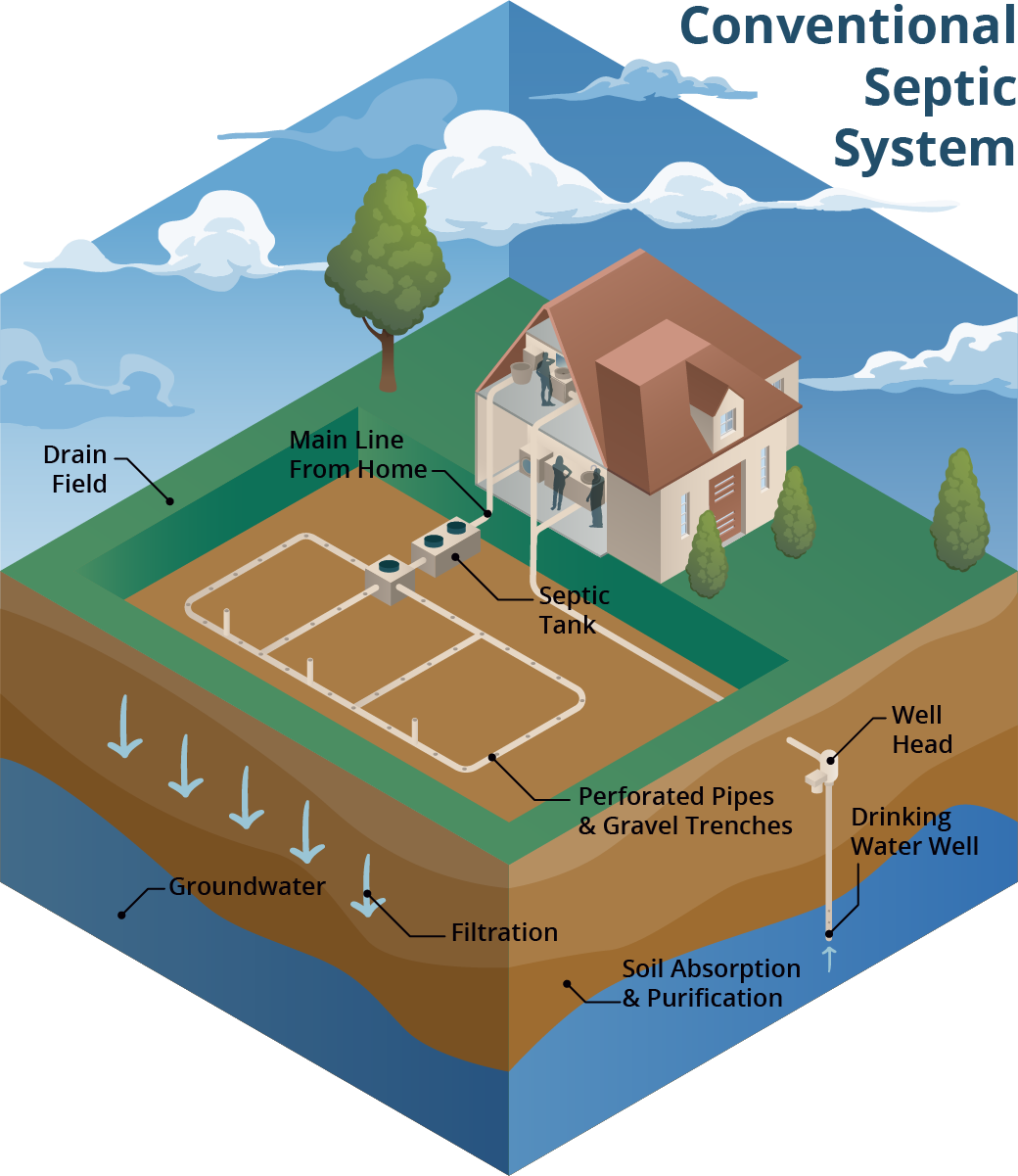

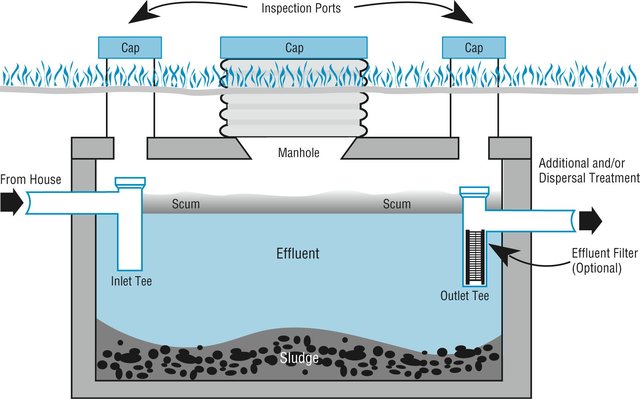

A conventional septic system is made up of a septic tank (a watertight container buried in the gound) and a drainfield. Image: Soil and Water Science Lab UF/IFAS GREC.

A conventional septic system is made up of a septic tank and a drainfield or leach field. Wastewater flows from the septic tank into the drainfield, which is typically made up of a distribution box (to ensure the wastewater is distributed evenly) and a series of trenches or a single bed with perforated PVC pipes. Wastewater seeps from these pipes into the surrounding soil. Most wastewater treatment occurs in the drainfield soil. When working properly, many contaminants, like harmful bacteria, are removed through die-off, filtering and interaction with soil surfaces.

What should you do if flooding occurs?

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) offers these guidelines:

- Relieve pressure on the septic system by using it less or not at all until floodwaters recede and the soil has drained. Under flooded conditions, wastewater can’t drain in the drainfield and can back up in your septic system and household drains. Clean up floodwater in the house without dumping it into the sinks or toilet. This adds additional water that an already saturated drainfield won’t be able to process. Remember that in most homes all water sent down the pipes goes into the septic system.

- Avoid digging around the septic tank and drainfield while the soil is waterlogged. Don’t drive vehicles or equipment over the drainfield. Saturated soil is very susceptible to compaction. By working on your septic system while the soil is still wet, you can compact the soil in your drainfield, and water won’t be able to drain properly. This reduces the drainfield’s ability to treat wastewater and leads to system failure.

- Don’t open or pump the septic tank if the soil is waterlogged. Silt and mud can get into the tank if it is opened and can end up in the drainfield, reducing its drainage capability. Pumping under these conditions can cause a tank to float or ‘pop out’ of the ground, and can damage inlet and outlet pipes.

- If you suspect your system has been damaged, have the tank inspected and serviced by a professional. How can you tell if your system is damaged? Signs include: settling, wastewater backs up into household drains, the soil in the drainfield remains soggy and never fully drains, a foul odor persists around the tank and drainfield.

- Keep rainwater drainage systems away from the septic drainfield. As a preventive measure, make sure that water from roof gutters doesn’t drain towards or into your septic drainfield. This adds an additional source of water that the drainfield has to process.

- Have your private well water tested if your septic system or well were flooded or damaged in any way. Your well water may not be safe to drink or use for household purposes (making ice, cooking, brushing teeth or bathing). You need to have it tested by the Health Department or other certified laboratory for total coliform bacteria and coli to ensure it is safe to use.

For more information on septic system maintenance after flooding, go to:

More information on having your well water tested can be found at:

More Information on conventional and advanced treatment septic systems can be found on the UF/IFAS Septic System website

by Andrea Albertin | May 3, 2019

The major goal of the Wakulla Springs Basin Management Action Plan (BMAP) is to reduce nitrogen loads to Wakulla Springs. Septic systems are identified as the primary source of this nitrogen. Photo: A. Albertin

A Basin Management Action Plan, or BMAP, is a management plan developed for a waterbody (like a spring, river, lake, or estuary) that does not meet the water quality standards set by the state. One or more pollutants can impair a waterbody. In Florida, the most common pollutants are nutrients (particularly nitrate), pathogens (fecal coliform bacteria) and mercury.

The goal of the BMAP is to reduce the pollutant load to meet water quality standards set by the Florida Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP). BMAPS are roadmaps with a list of projects and management action items to reach these standards. FDEP develops them with stakeholder input. Targets are set at 20 years, and progress towards those targets is assessed every five years.

It’s important to understand that a BMAP encompasses the entire land area that contributes water to a given waterbody. For example, the land area that contributes water to Jackson Blue Springs and Merritts Mill Pond (either from surface waters or groundwater flow) is 154 square miles, while the Wakulla Springs Basin covers an area of 1,325 square miles.

BMAPs in the Panhandle

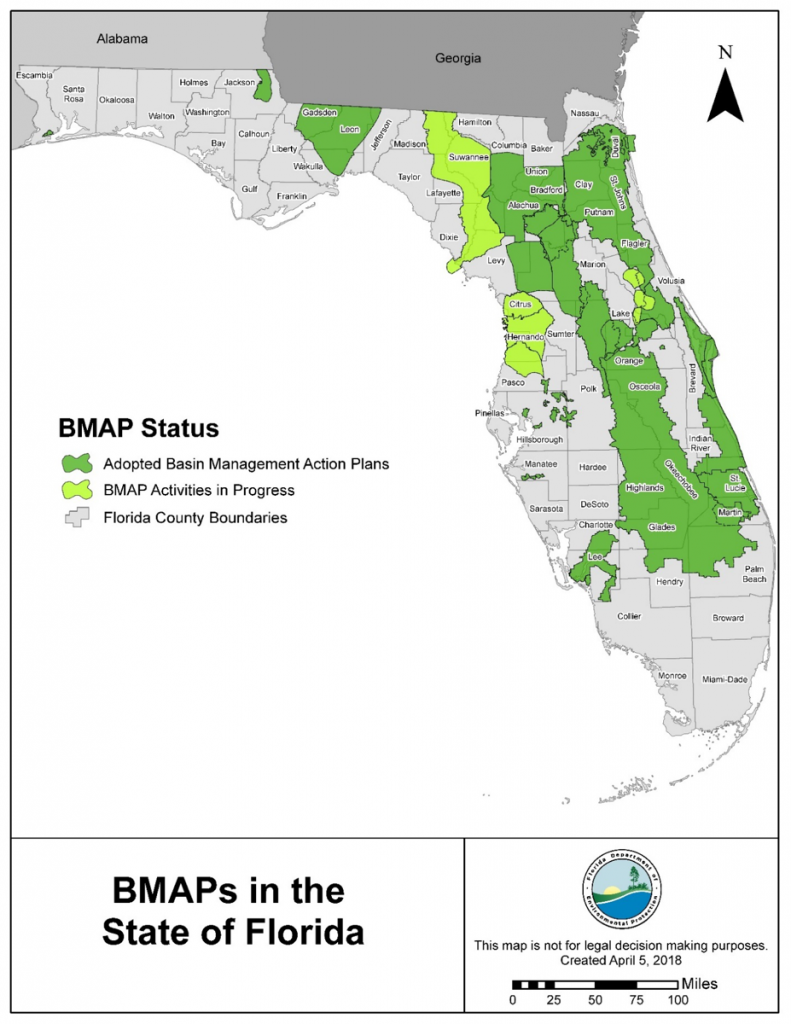

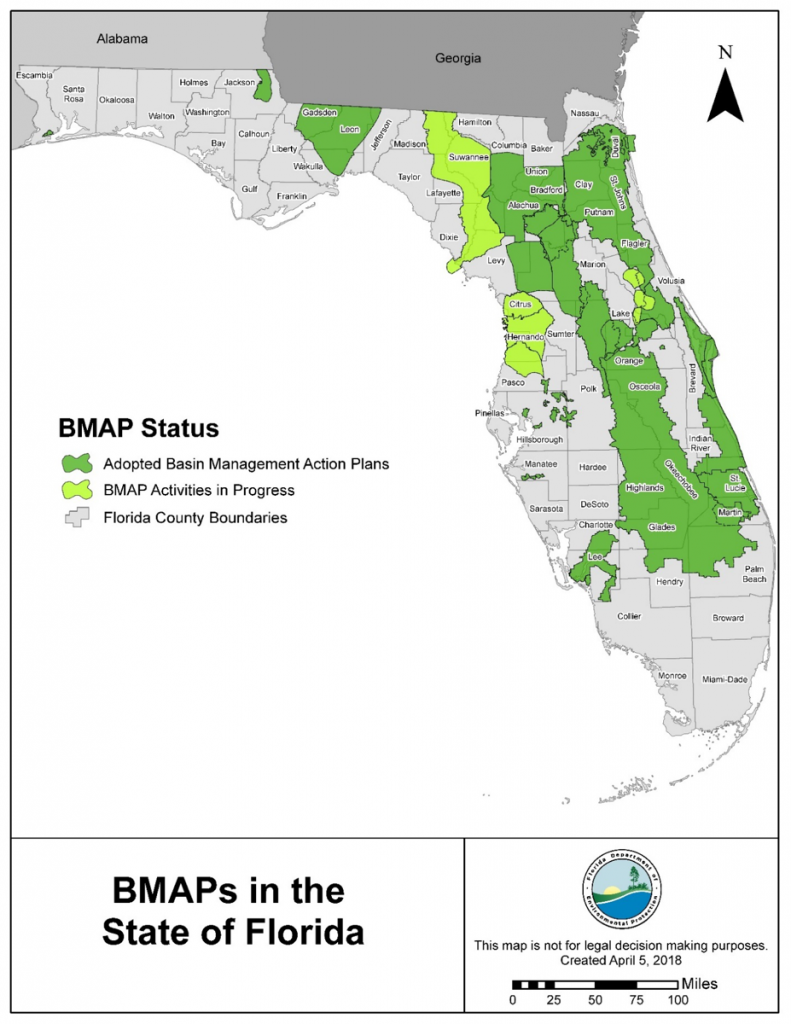

There are 33 adopted BMAPS in the state, and 5 that are pending adoption. Here in the Panhandle, we have three adopted BMAPS. They are the Bayou Chico BMAP in Escambia County, the Wakulla Springs BMAP in Wakulla, Leon, Gadsden and small parts of Jefferson County, and the Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond BMAP in Jackson County. All three are impaired for different reasons.

- Bayou Chico discharges into Pensacola Bay and is polluted by fecal coliform bacteria. The BMAP addresses ways to reduce coliforms from humans and pets, which includes sewer expansion projects, stormwater runoff management, septic tank inspections, pet waste ordinances and a Clean Marina and Boatyard program.

- Wakulla Springs Nitrate from human waste is the main pollutant to Wakulla Springs, and Tallahassee’s wastewater treatment facility and the city’s Southeast Sprayfield were identified as the main sources. Both sites were upgraded (the sprayfield was moved), greatly reducing nitrate contributions to the spring basin. The BMAP is focused on septic systems and septic to sewer hookups.

- Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond Nitrate is also the primary pollutant to the Jackson Blue/Merritts Mill Pond Basin, but nitrogen fertilizer from agriculture is identified as the main source. This BMAP focuses on farmers implementing Best Management Practices (BMPs), land acquisition by the Northwest Florida Water Management District , as well as septic tanks, recognizing their nitrogen contribution to Merritts Mill Pond.

Once all the BMAPS are adopted, FDEP states that almost 14 million acres will be under active basin management, an area that includes more than 6.5 million Floridians.

Adopted and pending BMAPS in Florida. Source: FDEP Statewide Annual Report, June 2018

How are residents living in an area with a BMAP affected? It varies by BMAP and specifically land use within its boundaries. For example, in BMAPs where nitrogen from septic systems are found to be a major source of nutrient impairment to a water body, septic to sewer hookups, or septic system upgrades to more advanced treatment units will be required in specific areas. In urban areas where nitrogen fertilizer is an important source, municipalities are required to adopt fertilizer ordinances. Where nitrogen fertilizer from agricultural production is a major source of impairment, producers are required to implement Best Management Practices to reduce nitrogen loads.

More information about BMAPS

For specific information on BMAPS, FDEP has an excellent website: https://floridadep.gov/dear/water-quality-restoration/content/basin-management-action-plans-bmaps All BMAPs (full reports with specific action items listed) can be found there, along with maps, information about upcoming meetings and webinars and other pertinent information.

Your local Health Department Office is the best resource regarding septic systems and any ordinances that may apply to you depending on where you live. Your Water Management District (in the Panhandle it’s the Northwest Florida Water Management District) is also an excellent resource and staff can let you know whether or not you live or farm in an area with a BMAP and how that may affect you.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 17, 2018

Being in the panhandle of Florida you may, or may not, have heard about the water quality issues hindering the southern part of the state. Water discharged from Lake Okeechobee is full of nutrients. These nutrients are coming from agriculture, unmaintained septic tanks, and developed landscaping – among other things. The discharges that head east lead to the Indian River Lagoon and other Intracoastal Waterways. Those heading west, head towards the estuaries of Sarasota Bay and Charlotte Harbor.

A large bloom of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria) in south Florida waters.

Photo: NOAA

Those heading east have created large algal blooms of blue-green algae (cyanobacteria). The blooms are so thick the water has become a slime green color and, in some locations, difficult to wade. Some of developed skin rashes from contacting this water. These algal blooms block needed sunlight for seagrasses, slow water movement, and in the evenings – decrease needed dissolved oxygen. When the algae die, they begin to decompose – thus lower the dissolved oxygen and triggering fish kills. It is a mess – both environmentally and economically.

On the west coast, there are red tides. These naturally occurring events happen most years in southwest Florida. They form offshore and vary in intensity from year to year. Some years beachcombers and fishermen barely notice them, other years it is difficult for people to walk the beaches. This year is one of the worst in recent memories. The increase in intensity is believed to be triggered by the increase in nutrient-filled waters being discharged towards their area.

Dead fish line the beaches of Panama City during a red tide event in the past.

Photo: Randy Robinson

On both coasts, the economic impact has been huge and the quality of life for local residents has diminished. Many are pointing the finger at the federal government who, through the Army Corp of Engineers, controls flow in the lake. Others are pointing the finger at shortsighted state government, who have not done enough to provide a reserve to discharge this water, not enforced nutrient loads being discharged by those entities mentioned above. Either way, it is a big problem that has been coming for some time.

As bad as all of this is, how does this impact us here in the Florida panhandle?

Though we are not seeing the impacts central and south Florida are currently experiencing, we are not without our nutrient discharge issues. Most of Florida’s world-class springs are in our part of the state. In recent years, the water within these springs have seen an increase in nutrients. This clouds the water, changing the ecology of these systems and has already affected glass bottom boat tours at some of the classic springs. There has also been a decline in water entering the springs due to excessive withdrawals from neighboring communities. The increase in nutrients are generally from the same sources as those affecting south Florida.

Florida’s springs are world famous. They attracted native Americans and settlers; as well as tourists and locals today.

Photo: Erik Lovestrand

Though we are not seeing large algal blooms in our local estuaries, there are some problems. St. Joe Bay has experienced some algal blooms, and a red tide event, in recent years that has forced the state to shorten the scallop season there – this obviously hurts the local economy. Due to stormwater runoff issues and septic tanks maintenance problems, health advisories are being issued due to high fecal bacteria loads in the water. Some locations in the Pensacola area have levels high enough that advisories must be issued 30% of the time they are sampled – some as often as 40%. Health advisories obviously keep tourists out of those waterways and hurt neighboring businesses as well as lower the quality of life for those living there.

Then of course, there is the Apalachicola River issue. Here, water that normally flows from Georgia into the river, and eventually to the bay, has been held back for water needs in Georgia. This has changed flow and salinity within the bay, which has altered the ecology of the system, and has negatively impacted one of the more successful seafood industries in the state. The entire community of Apalachicola has felt the impact from the decision to hold the water back. Though the impacts may not be as dramatic as those of our cousins in south Florida, we do have our problems.

Bay Scallop Argopecten iradians

http://myfwc.com/fishing/saltwater/recreational/bay-scallops/

What can we do about it?

The quick answer is reduce our nutrient input.

The state has adopted Best Management Practices (BMPs) for farmers and ranchers to help them reduce their impact on ground water and surface water contamination from their lands. Many panhandle farmers and ranchers are already implementing these BMPs and others can. We encourage them to participate. Read more at Florida’s Rangeland Agriculture and the Environment: A Natural Partnership – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2015/07/18/floridas-rangeland-agriculture-and-the-environment-a-natural-partnership/.

As development continues to increase across the state, and in the panhandle, sewage infrastructure is having trouble keeping up. This forces developments to use septic tanks. Many of these septic systems are placed in low-lying areas or in soils where they should not be. Others still are not being maintained property. All of this leads to septic leaks and nutrients entering local waterways. We would encourage local communities to work with new developments to be on municipal sewer lines, and the conversion of septic to sewer in as many existing septic systems as possible. Read more at Maintaining Your Septic Tank – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2017/04/29/maintain-your-septic-system-to-save-money-and-reduce-water-pollution/.

And then there are the lawns. We all enjoy nice looking lawns. However, many of the landscaping plans include designs that encourage plants that need to be watered and fertilized frequently as well as elevations that encourage runoff from our properties. Following the BMPs of the Florida Friendly Landscaping ProgramTM can help reduce the impact your lawn has on the nutrient loads of neighboring waterways. Read more at Florida Friendly Yards – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2018/06/08/restoring-the-health-of-pensacola-bay-what-can-you-do-to-help-a-florida-friendly-yard/.

For those who have boats, there is the Clean Boater Program. This program gives advice on how boaters can reduce their impacts on local waterways. Read more at Clean Boater – https://floridadep.gov/fco/cva/content/clean-boater-program.

One last snippet, those who live along the waterways themselves. There is a living shoreline program. The idea is return your shoreline to a more natural state (similar to the concept of Florida Friendly LandscapingTM). Doing so will reduce erosion of your property, enhance local fisheries, as well as reduce the amount of nutrients reaching the waterways from surrounding land. Installing a living shoreline will take some help from your local extension office. The state actually owns the land below the mean high tide line and, thus, you will need permission (a permit) to do so. Like the principals of a Florida Friendly Yard, there are specific plants you should use and they should be planted in a specific zone. Again, your county extension office can help with this. Read more at The Benefits of a Living Shoreline – https://nwdistrict.ifas.ufl.edu/nat/2017/10/06/the-benefits-of-a-living-shoreline/.

Though we may not be experiencing the dramatic problems that our friends in south Florida are currently experiencing, we do have our own problems here in the panhandle – and there is plenty we can do to keep the problems from getting worse. Please consider some of them. You can always contact your local county extension office for more information.

by Andrea Albertin | Jun 8, 2018

Flooding along the South Prong of the Black Creek River in Clay County on September 13, 2017. Photo credit: Tim Donovan, Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission (FWC).

As hurricane season is upon us again, I wanted to share the results of work that UF/IFAS Extension staff did with collaborators from Virginia Tech and Texas A&M University to help private well owners impacted by Hurricanes Irma and Harvey last year. This work highlights just how important it is to be prepared for this year’s hurricane season and to make sure that if flooding does occur, those that depend on private wells for household use take the proper precautions to ensure the safety of their drinking water.

About 2.5 million Floridians (approximately 12% of the population) rely on private wells for home consumption. While public water systems are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency to ensure safe drinking water, private wells are not regulated. Private well users are responsible for ensuring the safety of their own water.

Hurricanes Irma and Harvey

In response to widespread damage and flooding caused by Hurricane Harvey in Texas and Irma in Florida in August and September 2017, Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University (VT) received a Rapid Research Response Grant from the National Science Foundation to offer free well water testing to homeowners impacted by flooding.

They partnered with Texas A&M AgriLife Extension’s Well Owner Network (run by Diane Boellstorff and Drew Gholson) and us, at UF/IFAS Extension to provide this service. The effort at VT was led by members of Marc Edward’s lab in the Civil Engineering Department: Kelsey Pieper, Kristine Mapili, William Rhoads, and Greg House.

VT made 1,200 sampling kits available in Texas and 500 in Florida, and offered free analysis for total coliform bacteria and E. coli as well as other parameters, including nitrate, lead, arsenic, iron, chloride, sodium, manganese, copper, fluoride, sulfate, and hardness (calcium and magnesium). Homeowners were also asked to complete a needs assessment questionnaire regarding their well system characteristics, knowledge of proper maintenance and testing, perceptions of the safety of their water and how to best engage them in future outreach and education efforts.

Response in the aftermath of Irma

Although the sampling kits were available, a major challenge in the wake of Irma was getting the word out as counties were just beginning to assess damage and many areas were without power. We coordinated the sampling effort out of Quincy, Florida, where I am based, and spread the word to extension agents in the rest of the state primarily through a group texting app, by telephone and by word of mouth. Extension agents in 6 affected counties (Lee, Pasco, Sarasota, Marion, Clay and Putnam) responded with a need for sample kits, and they in turn advertised sampling to their residents through press releases.

Residents picked up sampling kits and returned water samples and surveys on specified days and the samples were shipped overnight and analyzed at VT, in Blacksburg, VA. Anyone from nearby counties was welcome to submit samples as well. This effort complemented free well water sampling offered by multiple county health departments throughout the state.

In all, 179 water samples from Florida were analyzed at VT and results of the bacterial analysis are shown in the table below. Of 154 valid samples, 58 (38%) tested positive for total coliform bacteria, and 3 (2%) tested positive for E. coli. Results of the inorganic parameters and the needs assessment questionnaire are still being analyzed.

Table 1. Bacterial analysis of private wells in Florida after Hurricane Irma.

| County |

Number of samples (n) |

Positive for total coliform (n) |

Positive total coliform (%) |

Positive for E. coli (n) |

Positive for E. coli (%) |

| Citrus |

1 |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

| Clay |

13 |

5 |

38% |

0 |

0% |

| Hernando |

2 |

1 |

50% |

0 |

0% |

| Hillsborough |

1 |

1 |

100% |

0 |

0% |

| Marion |

19 |

5 |

26% |

1 |

5% |

| Monroe |

1 |

0 |

0% |

0 |

0% |

| Pasco |

40 |

19 |

48% |

1 |

3% |

| Putnam |

61 |

19 |

31% |

0 |

0% |

| Sarasota |

16 |

8 |

50% |

1 |

6% |

| Overall |

154 |

58 |

38% |

3 |

2% |

Of 630 samples analyzed in Texas over the course of 7 weeks post-Hurricane Harvey, 293 samples (47% of wells) tested positive for total coliform bacteria and 75 samples (2%) tested positive for E. coli.

What to do if pathogens are found

Following Florida Department of Health (FDOH) guidelines, we recommended well disinfection to residents whose samples tested positive for total coliform bacteria, or both total coliform and E. coli. This is generally done through shock chlorination by either hiring a well operator or by doing it yourself. The FDOH website provides information on potential contaminants, how to shock chlorinate a well and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water (http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/index.html).

UF/IFAS extension agents that led the sampling efforts in their respective counties were: Roy Beckford – Lee County; Brad Burbaugh – Clay County; Whitney Elmore – Pasco County; Sharon Treen – Putnam and Flagler Counties; Abbey Tyrna – Sarasota County and Yilin Zhuang – Marion County.

We at IFAS Extension are working on using results from this sampling effort and the needs assessment questionnaire filled out by residents to develop the UF/IFAS Florida Well Owner Network. Our goal is to provide residents with educational materials and classes to address gaps in knowledge regarding well maintenance, the importance of testing and recommended treatments when pathogens and other contaminants are present.

Remember: Get your well water tested if flooding occurs

It’s important to remember that if any flooding occurs on your property that affects your well and/or septic system, you should have your well water tested in a certified laboratory for pathogens (total coliform bacteria and E. coli) and any other parameters your local health department may recommend.

Most county health departments accept samples for water testing. You can also submit samples to a certified commercial lab near you. Contact your county health department for information about what to have your water tested for and how to take and submit the sample.

Contact information for county health departments can be found online at: http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/county-health-departments/find-a-county-health-department/index.html

You can search for laboratories near you certified by FDOH here: https://fldeploc.dep.state.fl.us/aams/loc_search.asp This includes county health department labs as well as commercial labs, university labs and others.

You should also have your well water tested at any time when:

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking your well water

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

Testing well water once a year is good practice to ensure the safety of your household’s drinking water.

by Andrea Albertin | May 4, 2018

Special care needs to be taken with a septic system after a flood or heavy rains. Photo credit: Flooding in Deltona, FL after Hurricane Irma. P. Lynch/FEMA

Approximately 30% of Florida’s population relies on septic systems, or onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS), to treat and dispose of household wastewater. This includes all water from bathrooms and kitchens, and laundry machines.

When properly maintained, septic systems can last 25-30 years, and maintenance costs are relatively low. In a nutshell, the most important things you can do to maintain your system is to make sure nothing but toilet paper is flushed down toilets, reduce the amount of oils and fats that go down your kitchen sink, and have the system pumped every 3-5 years, depending on the size of your tank and number of people in your household.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

Image credit: wfeiden CC by SA 2.0

How does a traditional septic system work?

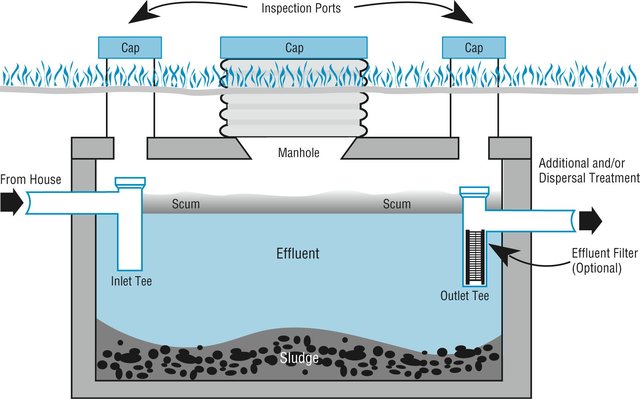

The most common type of OSTDS is a conventional septic system, made up of (1) a septic tank (above), which is a watertight container buried in the ground and (2) a drain field, or leach field. The effluent (liquid wastewater) from the tank flows into the drain field, which is usually a series of buried perforated pipes. The septic tank’s job is to separate out solids (which settle on the bottom as sludge), from oils and grease, which float to the top and form a scum layer. Bacteria break down the solids (the organic matter) in the tank. The effluent, which is in the middle layer of the tank, flows out of the tank and into the drain field where it then percolates down through the ground.

During floods or heavy rains, the soil around the septic tank and in the drain field become saturated, or water-logged, and the effluent from the septic tank can’t properly drain though the soil. Special care needs to be taken with your septic system during and after a flood or heavy rains.

What should you do after flooding occurs?

- Relieve pressure on the septic system by using it less or not at all until floodwaters recede and the soil has drained. For your septic system to work properly, water needs to drain freely in the drain field. Under flooded conditions, water can’t drain properly and can back up in your system. Remember that in most homes all water sent down the pipes goes into the septic system. Clean up floodwater in the house without dumping it into the sinks or toilet.

- Avoid digging around the septic tank and drain field while the soil is water logged. Don’t drive heavy vehicles or equipment over the drain field. By using heavy equipment or working under water-logged conditions, you can compact the soil in your drain field, and water won’t be able to drain properly.

- Don’t open or pump out the septic tank if the soil is still saturated. Silt and mud can get into the tank if it is opened, and can end up in the drain field, reducing its drainage capability. Pumping under these conditions can also cause a tank to pop out of the ground.

- If you suspect your system has been damage, have the tank inspected and serviced by a professional. How can you tell if your system is damaged? Signs include: settling, wastewater backs up into household drains, the soil in the drain field remains soggy and never fully drains, and/or a foul odor persists around the tank and drain field.

- Keep rainwater drainage systems away from the septic drain field. As a preventive measure, make sure that water from roof gutters doesn’t drain into your septic drain field – this adds an additional source of water that the drain field has to manage.

More information on septic system maintenance after flooding can be found on the EPA website publication https://www.epa.gov/ground-water-and-drinking-water/septic-systems-what-do-after-flood

By taking special care with your septic system after flooding, you can contribute to the health of your household, community and environment.