by Andrea Albertin | Mar 18, 2018

An estimated 2.5 million Floridians (approximately 12% of the population) rely on private wells for home consumption, which includes water for drinking, cooking, bathing, washing, toilet flushing and other needs. While public water systems are regulated by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) to ensure safe drinking water, private wells are not regulated. Private well users are responsible for ensuring the safety of their own drinking water.

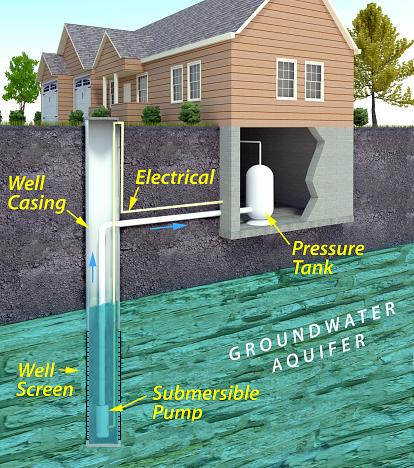

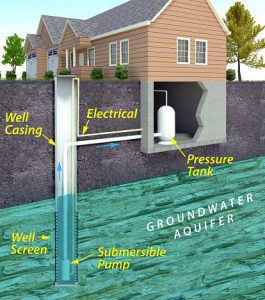

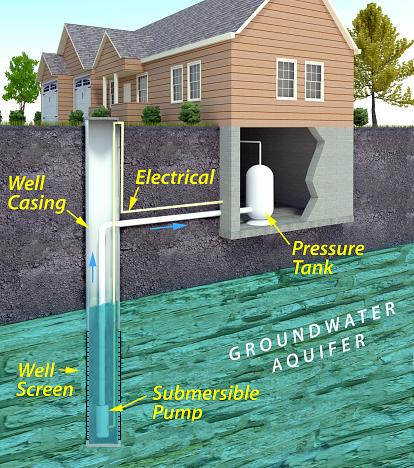

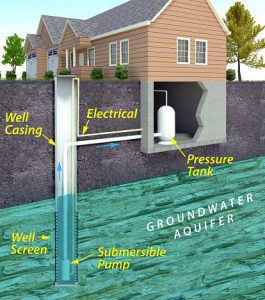

Schematic of a private well typical of many areas in the U.S. Source: usepa.gov

The In Florida, pressure tanks are located above ground since basements are not common. The well casing ensures that water is drawn from the desired ground water source – the bottom of the well where the well screen is placed. The screen keeps sediment from getting into the well, and is usually made of perforated or slotted pipe. The well cap on the surface prevents debris and animals from getting into the well. Submersible pumps (shown here) are set inside the well casing and used for deep wells. Jet pumps are used on the surface and can be used for both shallow and deep wells.

How can well users make sure that their water is safe to drink?

It’s important to have well water tested at a certified laboratory at least once a year for contaminants that can cause health problems. According to the Florida Department of Health (FDOH), the most common contaminants in well water in Florida are bacteria and nitrates.

Bacteria: Labs generally test for Total coliform bacteria and fecal coliforms (or E. coli specifically) when a sample is submitted for bacteriological testing. This generally costs about $25 to $30, but can vary depending on where you have your sample analyzed.

Coliform bacteria are a large group of different kinds of bacteria and most species are harmless and will not make you sick. But, a positive test for total coliforms indicate that bacteria are getting into your well water. Coliforms are used as indicator organisms – if coliform bacteria are in your well, other pathogens (bacteria, viruses or protozoans) that cause diseases may also be getting into your well water. It is easier and cheaper to test for total coliforms than a suite of bacteria and other organisms that can cause health problems.

Fecal coliform bacteria are a subgroup of coliform bacteria found in human and other warm-blooded animal feces. E. coli are one species of fecal coliform bacteria. A positive test for fecal coliform bacteria or E. coli indicate that water has been contaminated by human or animal waste.

If your water sample tests positive for only total coliform bacteria or both total coliform and fecal coliform (or E. coli), the Department of Health recommends that your well be disinfected. This is generally done through shock chlorination. You can either hire a well operator in your area to disinfect your well or you can do it yourself. Information for how to shock chlorinate your own well can be found

Nitrates: The U.S. EPA set the Maximum Contaminant Level (MCL) for nitrate in drinking water at 10 miligrams per liter of water (mg/L). Values above this are a concern for infants who are less than 6 months old because high nitrate levels can cause a type of “blue baby syndrome” (methemoglobinemia), where nitrate interferes with the capacity of hemoglobin in the blood to carry oxygen. It is particularly important to test for nitrate if you have a young infant in the home that will be drinking well water or when well water will be used to make formula to feed the infant.

If test results come back above 10 mg/L, never boil nitrate contaminated water as a form of treatment. This will not remove nitrates. Use water from a tested source (bottled water or water from a public supply source) until the problem is addressed.

Nitrates in well water come from fertilizers applied on land surfaces, animal waste and/or human sewage, such as from a septic tank. Have your well inspected by a professional to identify why elevated nitrate levels are is getting into your well water. You can also consider installing a water treatment system, such as reverse osmosis or distillation units to treat the contaminated water. Before having a system installed, make sure you contact your local health department or a water treatment contractor for more information.

Where can you have your well water tested?

Most county health departments accept samples for water testing. You can also submit samples to a certified commercial lab near you. Contact your county health department for information about what to have your water tested for and how to take and submit the sample.

Contact information for county health departments can be found on this site: http://www.floridahealth.gov/programs-and-services/county-health-departments/find-a-county-health-department/index.html

You can search for laboratories near you certified by FDOH here: https://fldeploc.dep.state.fl.us/aams/loc_search.asp This includes county health department labs as well as commercial labs, university labs and others.

You should also have your well water tested at any time when:

- The color, taste or odor of your well water changes or if you suspect that someone became sick after drinking your well water.

- A new well is drilled or if you have had maintenance done on your existing well

- A flood occurred and your well was affected

Remember: Bacteria and nitrate are by no means the only parameters that well water is tested for. Call your local health department to discuss your water and what they recommend you should get the water tested for. The Florida Department of Health (FDOH) also maintains an excellent website with many resources for private well users: http://www.floridahealth.gov/environmental-health/private-well-testing/index.html . This site includes information on potential contaminants and how to maintain your well to ensure the quality of your well water.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 29, 2017

ARTICLE BY DR. MATT DEITCH; water quality specialist – University of Florida Milton

Summer is a great time for weather-watching in the Florida panhandle. Powerful thunderstorms appear out of nowhere, and can pour inches of rain in an area in a single afternoon. Our bridges, bluffs, and coastline allow us to watch them develop from a distance. Yet as they come closer, it is important to recognize the potential danger they pose—lightning from these storms can strike anywhere nearby, and can cause fatality for a person who is struck. Nine people were killed by lightning strike in Florida in 2016 alone, more than in any other state. Because of the risk posed by lightning, my family and I enjoy these storms up-close from indoors.

Carpenter’s Creek in Pensacola

Photo: Dr. Matt Deitch

A fraction of the rain that falls during these storms is delivered to our bays, bayous, and estuaries through a drainage network of creeks and rivers. This streamflow serves several important ecological functions, including preventing vegetation encroachment and maintaining habitat features for fish and amphibians through scouring the streambed. High flows also deposit fine sediment on the floodplain, helping to replenish nutrients to floodplain soil. On average, only about one-third of the water that falls as rain (on average, more than 60 inches per year!) turns into streamflow. The rest may either infiltrate soil and percolate into groundwater; or be consumed and transpired by plants; or evaporate off vegetation, from the soil, or the ground surface before reaching the soil. Evaporation and transpiration play an especially large role in the water cycle during summer: on average, most of the rain that falls in the Panhandle occurs during summer, but most stream discharge occurs during winter.

The water that flows in streams carries with it many substances that accumulate in the landscape. These substances—which include pollutants we commonly think of, such as excessive nutrients comprised of nitrogen and phosphorus, as well as silt, oil, grease, bacteria, and trash—are especially abundant when streamflow is high, typically during and following storm events. Oil, grease, bacteria, and trash are especially common in urban areas. The United States EPA and Florida Department of Environmental Protection have listed parts of the Choctawhatchee, St. Andrew, Perdido, and Pensacola Bays as impaired for nutrients and coliform bacteria. Pollution issues are not exclusive to the Panhandle: some states (such as Maryland and California) have even developed regulatory guidelines in streams (TMDLs) for trash!

Many local and grassroots organizations are taking the lead on efforts to reduce pollution. Some municipalities have recently publicized efforts to enforce laws on picking up pet waste, which is considered a potential source of coliform bacteria in some places. Some conservation groups in the panhandle organize stream debris pick-up days from local streams, and others organize volunteer citizens to monitor water quality in streams and the bays where they discharge. Together, these efforts can help to keep track of pollution levels, demonstrate whether restoration efforts have improved water quality, and maintain healthy beaches and waterways we rely on and value in the Florida Panhandle.

Santa Rosa Sound

Photo: Dr. Matt Deitch

by Andrea Albertin | Apr 29, 2017

One third of homes in Florida rely on septic systems, or onsite sewage treatment and disposal systems (OSTDS), to treat and dispose of household wastewater, which includes wastewater from bathrooms, kitchen sinks and laundry machines. When properly maintained, septic systems can last 25-30 years, and maintenance costs are relatively low.

A conventional residential septic tank and drain field under construction.

Photo: Andrea Albertin

A general rule of thumb is that with proper care, systems need to be pumped every 3-5 years at a cost of about $300 to $400. Time between pumping does vary though, depending on the size of your household, the size of your septic tank and how much wastewater you produce. If systems aren’t maintained they can fail, and repairs or replacing a tank can cost anywhere between $3000 to $10,000. It definitely pays off to maintain your septic system!

The most common type of OSTDS is a conventional septic system, which is made up of a septic tank (a watertight container buried in the ground) and a drain field, or leach field. The septic tank’s job is to separate out solids (which settle on the bottom as sludge), from oils and grease, which float to the top and form a scum layer. The liquid wastewater, which is in the middle layer of the tank, flows out through pipes into the drainfield, where it percolates down through the ground.

Although bacteria continually work on breaking down the organic matter in your septic tank, sludge and scum will build up, which is why a system needs to be cleaned out periodically. If not, solids will flow into the drainfield clogging the pipes and sewage can back up into your house. Overloading the system with water also reduces its ability to work properly by not leaving enough time for material to separate out in the tank, and by flooding the system. Sewage can flow to the surface of your lawn and/or back up into your house.

Failed septic systems not only result in soggy lawns and horrible smells, but they contaminate groundwater, private and public supply wells, creeks, rivers and many of our estuaries and coastal areas with excess nutrients, like nitrogen, and harmful pathogens, like E. coli.

It is important to note that even when traditional septic systems are maintained, they are still a source of nitrogen to groundwater; nitrate is not fully removed from the wastewater effluent.

How can you properly care for your septic system?

Here are a some basic tips to keep your system working properly so that you can reduce maintenance costs by avoiding system failure, and so that you can reduce your household’s impact on water pollution in your area.

- Don’t flush trash down the toilet. Only flush regular toilet paper. Toilet paper treated with lotion forms a layer of scum. Wet wipes are not flushable, although many brands are labelled as such. They wreak havoc on septic systems! Avoid flushing cigarette butts, paper towels and facial tissues, which can take longer to break down than toilet paper.

- Think at the sink. Avoid pouring oil and fat down the kitchen drain. Avoid excessive use of harsh cleaning products and detergents, which can affect the microbes in your septic tank (regular weekly or so cleaning is fine). Prescription drugs and antibiotics should never be flushed down the toilet.

- Limit your use of the garbage disposal. Disposals add organic matter to your septic system, which results in the need for more frequent pumping. Composting is a great way to dispose of your fruit and vegetable scraps instead.

- Take care at the surface of yourtank and drainfield. To work well, a septic system should be surrounded by non-compacted soil. Don’t drive vehicles or heavy equipment over the system. Avoid planting trees or shrubs with deep roots that could disrupt the system or plug pipes. It is a good idea to grow grass over the drainfield to stabilize soil and absorb liquid and nutrients.

- Conserve water. You can reduce the amount of water pumped into your septic tank by reducing the amount you and your family use. Water conservation practices include repairing leaky faucets, toilets and pipes, installing low cost, low-flow showerheads and faucet aerators, and only running the washing machine and dishwasher when full. In the US, most of the household water used is to flush toilets (about 27%). Placing filled water bottles in the toilet tank is an inexpensive way to reduce the amount of water used per flush.

- Have your septic system pumped by a certified professional. The general rule of thumb is every 3-5 years, but it will depend on household size, the size of your septic tank and how much wastewater you produce.

By following these guidelines, you can contribute to the health of your family, community and environment, as well as avoid costly repairs and septic system replacements.

You can find excellent information on septic systems a the US EPA website: https://www.epa.gov/septic. The Florida Department of Health website provides permiting information for Florida and a list of certified maintenance entities by county: http://www.floridahealth.gov/Environmental-Health/onsite-sewage/index.html.

The Department of Environmental Protection (FDEP) identified septic systems as the major source of nitrate in Wakulla Springs, located in Wakulla County. Excess nitrate is thought to promote algal growth, leading to the degradation of the biological community in the spring.

Photo: Andrea Albertin

by Rick O'Connor | Apr 14, 2017

The Deepwater Horizon Oil Spill was one of the worst natural disasters in our country’s history.

Photo: Gulf Sea Grant

We are pleased to announce the release of a pair of new bulletins outlining how the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill impacted the popular marine animals dolphins and sea turtles. To read these and other oil spill science publications, go to http://gulfseagrant.org/oilspilloutreach/publications/.

The Deepwater Horizon’s impact on bottlenose dolphins – In 2010, scientists documented a markedly increased number of stranded dolphins in the northern Gulf of Mexico. Was oil exposure to blame? Could other factors have been in play? Read the answers to these questions here: http://masgc.org/oilscience/oil-spill-science-dolphins.pdf.

Sea turtles and the Deepwater Horizon oil spill – This publication reviews the estimated damage oil exposure caused to sea turtles and discusses continued research and monitoring efforts for these already endangered and threatened species. Click here to read this bulletin: http://masgc.org/oilscience/oil-spill-science-sea-turtles.pdf.

Also –

“Sea turtles and oil spills” presentations – On March 23 in Brownsville, Texas, more than 100 participants gathered in person and online to listen to scientists, responders, and sea turtle specialists explain what we know about how these creatures fared in 2010 and detail ongoing conservation programs. Watch videos of the presentations here: http://gulfseagrant.org/sea-turtles-oil-spills/.

Our oil spill science outreach team hopes you will find these resources useful! J

by Andrea Albertin | Mar 11, 2017

Stormwater runoff is water from rainfall that flows along the land surface. This runoff usually finds its way into the nearest ditch or water body, such as a river, stream, lake or pond. Generally speaking, in natural undeveloped areas only 10% of rainfall is runoff. About 40% returns to the atmosphere though evapotranspiration, which is the water evaporated from land and plant surfaces plus water lost directly from plants to the atmosphere through their leaves. The remaining 50% of rainfall soaks into the ground, supporting vegetation, contributing to streamflow and replenishing groundwater resources. In Florida, where 90% of the population relies on groundwater for their drinking water, aquifer recharge from infiltrating rainwater is vital.

Stormwater runoff from a drainage pipe flowing into a creek.

Photo: Andrea Albertin

As landscapes become more developed, areas that use to absorb rainwater are replaced by impervious surfaces like rooftops, driveways, parking lots and roads. Additionally, we are levelling our land, removing natural depressions in the landscape that trap rainwater and give it time to seep back into the ground. As a result, a higher percentage of rainfall is becoming runoff and which flow at faster rates into storm drainages and nearby water bodies instead of soaking into the soil.

A major problem with stormwater runoff is that as it flows over surfaces, it picks up potential pollutants that end up in our waterways. These include trash, sediment, fertilizer and pesticides from lawns, bacteria from dog waste, metals from rooftops, and oil from parking lots and roads. Stormwater runoff is often the main cause of surface water pollution in urban areas.

Luckily, there are ways in which we can all help slow the flow and reduce stormwater runoff. These reductions can give rainfall more time to soak back into the ground and replenish our needed stores of groundwater.

What can you do to help “slow the flow” of stormwater?

The UF/IFAS Florida Friendly Landscaping Program provides the following recommendations that you, as a homeowner, can do to reduce stormwater runoff from your property:

- Direct your downspouts and gutters to drain onto the lawn, plant beds, or containment areas, so that rain soaks into the soil instead of running off the yard.

- Use mulch, bricks, flagstone, gravel, or other porous surfaces for walkways, patios, and drives.

- Reduce soil erosion by planting groundcovers on exposed soil such as under trees or on steep slopes

- Collect and store runoff from your roof in a rain barrel or cistern.

- Create swales (low areas), rain gardens or terracing on your property to catch, hold, and filter stormwater.

- Pick up after your pets.

- Clean up oil spills and leaks on the driveway. Instead of using soap and water, spread cat litter over oil, sweep it up and then throw away in the trash.

- Sweep grass clippings, fertilizer, and soil from driveways and streets back onto the lawn. Remove trash from street gutters before it washes into storm drains. The City of Tallahassee’s TAPP (Think About Personal Pollution) Campaign is another excellent resource for ways in which you can help reduce stormwater runoff (http://www.tappwater.org/).

- For more information on stormwater management on your property and other Florida Friendly Landscaping principles, you can visit the Florida Friendly Landscaping website at: https://ffl.ifas.ufl.edu.

TAPP also provides a manual for homeowners on how to build a raingarden, which can be found at http://tappwaterapp.com/what-can-i-do/build-a-rain-garden/. Raingardens are small depressions (either naturally occurring or created) that are planted with native plants. They are designed to temporarily catch rainwater, giving it time to slowly soak back into the ground.

Grass covered drainage ditches slow the flow of stormwater runoff and allow more rainwater to soak back into the ground.

Photo: Andrea Albertin

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 31, 2016

Most of us have heard about the toxic algal blooms plaguing south Florida waters. If not, check out http://www.cnbc.com/2016/07/05/. This bloom has caused several major fish kills, bad odors, and has kept tourist away from the area. What happen? and could it happen in the panhandle?

One of the many lock systems that controls water flow in Lake Okeechobee.

Photo: Florida Sea Grant

First we have to understand what happened in south Florida. The source of the problem is Lake Okeechobee. This large freshwater lake has been diked and channeled over the years to supply water to cities and farms in south Florida. The flow of water in and out of the lake is controlled by the Army Corp of Engineers. Typically, this time of year they manage the level of water within the lake to prepare for both the rainy and hurricane seasons. To do this they allow water to flow out into local rivers and canals. However, the water within the lake is heavy with nutrients. Fertilizers, leave matter, and animal waste are discharged into the lake from neighboring communities and agriculture fields. These nutrients fuel the rapid growth of plants and algae, which we call a bloom. These blooms can contain toxic forms of algae that can cause skin irritation and intestinal problems in humans, and can kill many forms of wildlife. Because the state is trying to restore the Everglades, lake water that test high for nutrients cannot be released in a southern direction but rather east and west towards the populated coasts.

But this year was different…

Due to heavy rainfall in spring the Corp had to release more water than they typically would. It was after this release that the large blooms along the east coast began to occur. The state declared a state of emergency and the flow of water out of the lake was altered. But for east Florida, the damage was done.

Could this happen in other parts of the state? Could it happen in the panhandle?

Well first, we have very few controlled water systems for drinking water (reservoirs) so that exact same scenario is a low probability. During a recent trip out west I camped several times along a reservoir designed to hold drinking water for municipalities. At each there were information signs warning swimmers about the potential of high levels of toxic cyanobacteria, particularly in late summer and early fall. But here most of our rivers flow unimpeded (relatively) to the Gulf of Mexico. Our drinking water instead comes from the ground.

But could our local waterways become contaminated with algae?

Yes…

With the situation going on in south Florida people of have pointed fingers at the Corp for releasing too much water. But because the water had high levels of nutrients, others have pointed the finger at the fact that we do not regulate nutrient discharge as well as we should. We have cities and farms here as well, and each produce and release nutrients in the form of leaf litter, animal waste, and fertilizers. Actually large fish kills have happened here. I remember seeing large masses of dead fish on the surface of Bayou Texar in Pensacola when I was younger; Bayou’s Chico and Grande had their problems as well. Most of these were due to excessive nutrients being released from developed areas in the local municipalities.

When I first joined Sea Grant I was told that water quality was a concern in the Pensacola area. Many remembered these large fish kills from a few decades ago and were still concerned about the quality of water in our area, particularly the bayous. I have worked with local non-profits, as well as state and county agencies, and the local high schools to monitor nutrients in the area. The nutrient of concern here is nitrogen. Several groups including the Bream Fishermen’s Association, Escambia County, UF/IFAS LAKEWATCH, and the School District’s Marine Science Academy routinely monitor for nitrogen. Others, such as the University of West Florida and the U.S. EPA, do so when they are working on such projects. Low nitrogen levels could mean less being discharged, but it could also mean that the algae have consumed it – so monitoring for chlorophyll (indicator for the presence of algae) is also important; and these groups do this as well. High levels of algae can trigger declines in dissolved oxygen, so this is monitored also. Low dissolved oxygen can trigger fish kills, and this data is collected by the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission. I try to collect as much of this data as I can and post it on our website each Friday on the Escambia County Extension website.

A large algal bloom in a south Florida waterway.

Photo: University of South Florida News

Yes, we have areas with relative high levels of nitrogen, when compared to other locations sampled. Dissolved oxygen levels are typically okay in the Pensacola Bay area, but most of the monitors are sampling in shallow water near shore. A UF/IFAS LAKEWATCH volunteer has recently started to monitor DO at depth in Perdido Bay. In the Pensacola Bay area, fish kills are down when compared to earlier decades.

2016 panhandle fish kills based on data from FWC

- Escambia/Santa Rosa Counties – 8 fish kills – 312 dead fish – cause for most is unknown

- Okaloosa/Walton – 12 fish kills – 1102 dead fish – cause for most is unknown

- Bay – 13 fish kills – 3092 dead fish – 3 of these were attributed to low DO – 2 in White Western Lake, 1 in Grand Lagoon

- Gulf – 5 fish kills – 719 dead fish – cause for most is in unknown – most were starfish

- Franklin – 1 dead sturgeon at St. Vincent Island

- Wakulla – 2 fish kills – 200 dead fish – cause was fishing net dump

- Jefferson – reported no fish kills so far this year.

There are fish kills occurring, the cause of most is unknown, but the numbers are much lower than they were a few decades ago and many are not related to the nutrient issue. However it is true that not all fish kills are reported to FWC. Many residents who discover one are not sure who to call or where to report. If you do discover a fish kill you can report it to the FWC at http://myfwc.com/research/saltwater/health/fish-kills-hotline/. We also experienced a large red tide event this past fall. Though red tides do occur naturally, and 2015 was an El Nino year with unusual rainfall patterns, they can be enhanced with increase nutrients in the run-off.

What we do have a problem with in many areas of the panhandle coast are health advisories. Some agencies, FDEP and Escambia County, monitor for fecal coliform bacteria locally. These are bacteria associated with the digestive system of birds and mammals, including humans, and are non-toxic. However, they are indicators that animal waste is in the water and that pathogenic bacteria associated with animals could be also. When samples are collected the number of bacteria colonies are counted. If the number is above what is allowed a re-sample is taken. If the second count is high as well a health advisory is issued. Many coastal waterways in the panhandle are fighting this problem. Based on FDEP data, the bayous of the Pensacola area average between 8-10 advisories each year. Not all bodies of water are monitored at the same frequency but our bayous are issued advisories between 25-35% of the time they are sampled. Most of the advisories occur after a heavy rainfall, suggesting the source of the animal waste is from run-off, but it could be related to leaky septic tanks systems as well.

So though the scenario that is occurring in south Florida is a low risk for our area, we do have some concerns and there are many things residents and citizens can do to help reduce the risk of a large problem occurring.

- Manage the amount of fertilizer you use. Whether you are a farmer, a lawn care company, or property owner, think about how much you are using and use only what your plants need. For assistance on this, contact your extension office.

- Reduce leaf litter from entering waterways. When raking we recommend you bag your leaves using the new paper bags. These can be composted at the landfill. If you have large amounts of leaves that cannot be bagged, consider composting yourself. The demonstration garden at your local extension office can show you several methods of composting.

- Pick up your animal waste. Our streets and parks are littered with pet waste that owners have not removed, even with the city and county providing plastic bag dispensers to do so. Please be aware of the problem with animal waste and help keep our streets and waterways clean.

- If you have a septic tank, maintain it properly. If you are not sure how to do this, contact your local extension office for advice.

If you have questions about local water quality issues, contact your local county extension office.