by Rick O'Connor | Jul 10, 2015

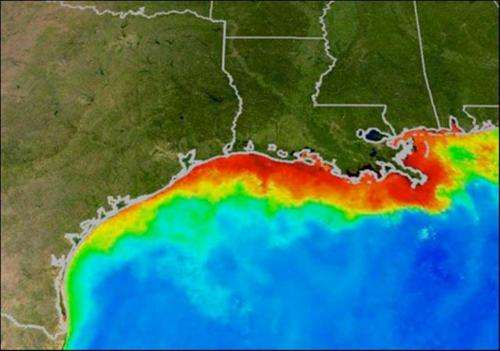

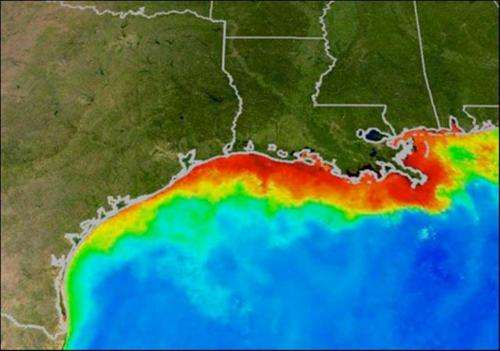

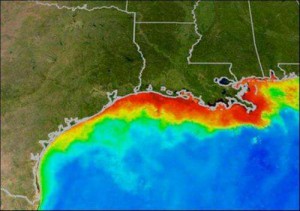

What is the Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone you ask? Well…it’s a layer of hypoxic water (low in dissolved oxygen) on the bottom of the Gulf of Mexico. It was first detected in the 1970’s but reached its peak in size in the 1990’s. The low levels of dissolved oxygen decrease the amount of marine life on the bottom of the Gulf within this zone, including many commercially valuable species supporting the Gulf seafood industry.

The red area indicates where dissolved oxygen levels are low.

What Causes this Dead Zone?

Drops in concentrations of dissolved oxygen within the water column can occur for a variety of reasons but is usually caused by one of two reasons. (1) Increasing water temperatures—as water temperature increases, its ability to hold dissolved oxygen decreases. (2) A process called eutrophication.

What is eutrophication?

Eutrophication is a process where an increase of nutrients in an aquatic system triggers an algal bloom of microscopic phytoplankton. These phytoplankton produce oxygen during the daylight hours but consume it in the evening. Once the bloom dies, decomposing bacteria begin to break them down and consume larger amounts of dissolved oxygen in doing so. When the dissolved oxygen concentrations drop below 2.0 mg/L we say the water is hypoxic and many marine organisms either begin to move out or die. The nutrients that trigger such blooms are primarily nitrates and phosphates. These can be introduced to the water column with plant and animal waste and with synthetically produced fertilizers we use on our fields and lawns. There is natural eutrophication, but when the process is triggered or accelerated by human activity we use the term cultural eutrophication.

So which is it; warming waters or eutrophication?

The Gulf of Mexico Dead Zone usually forms in spring and lasts through September. These are certainly the warmer months of the year, but the warmer waters are near the surface and much of the water column is not warm enough to cause this. Another point is that the Dead Zone is near Louisiana and there are warm locations in other parts of the Gulf where dead zones do not occur. However the Mississippi River does discharge near Louisiana. This river drains 41% of the continental United States, which contains 52% of the nation’s farms. The agricultural waste (plant, animal, and synthetic fertilizers) discharged into the Mississippi River contains nitrogen and phosphorus, the two key nutrients that trigger algal blooms. Based on this, most scientists agree that cultural eutrophication is the primary cause of the Gulf Dead Zone.

When they say it will be a “typical year”, what does that mean – what is a “typical year”?

Scientists from NOAA, the U.S. Geological Survey, and six partnering universities have released their annual forecast of the Dead Zone. The 2015 prediction has the area of the dead zone about equal to the size of Connecticut, which has been the average size for the past several years. This is what they mean by typical.

Can these dead zones occur in our area waters?

Yes, and they do. We do not typically call them “dead zones” but the same process occurs all over the world, including the bays of the Florida panhandle.

What can we do to reduce cultural eutrophication locally?

If you can do without fertilizing your lawn (or field), then do. If this is not an option then only put the amount of fertilizer required for your land/lawn. Most people over fertilize, which not only reduces water quality but is expensive for the property owners. If you can compost your plant waste, do so. With animal waste, please dispose of properly, in a manner where it not reach local waterways.

For more information on hypoxia, eutrophication, and solutions to reduce this problem, contact your county Extension office.

http://www.tulane.edu/~bfleury/envirobio/enviroweb/DeadZone.htm

http://www.iseca.eu/en/science-for-all/what-is-eutrophication

http://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/Features/Phytoplankton/

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 10, 2015

After the recent report of a fatality due to the Vibrio bacteria near Tampa many locals have become concerned about their safety when entering the Gulf of Mexico this time of year. So what are the risks and how do you protect yourself?

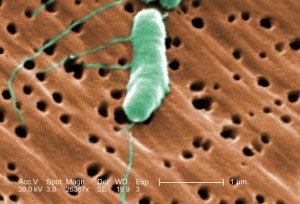

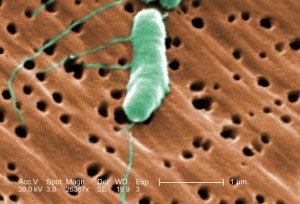

The rod-shaped bacterium known as Vibrio. Courtesy: Florida International University

What is the Flesh Eating Disease Vibrio?

Vibrio vulnificus is a salt-loving rod-shaped bacteria that is common in brackish waters. As with many bacteria, their numbers increase with increasing temperatures. Though the organism can be found year round they tend peak in July and August and remain elevated until temperature decline.

How do people contract Vibrio?

The most common methods of contact with Vibrio are entrance through open wounds exposed to seawater or marine animals and by consuming raw or undercooked shellfish, primarily oysters. The bacterium can also be contracted by eating food that is either served, and has made contact with, raw or undercooked shellfish or the juice of raw or undercooked shellfish.

What is the risk of serious health problems after contracting Vibrio?

Cases of Vibrio infection are rare and the risk of serious health problems is much higher for humans who are have a suppressed or compromised immune system, liver disease or blood disorders such as iron overload (hemochromatosis). Examples include HIV positive, in the process of cancer treatment, and studies show a particularly high risk for those with a chronic liver disease. The Center for Disease Control indicates that humans who are immunocompromised have an 80 times higher chance of serious health issues from Vibrio than healthy people. He also found that most cases involve males over the age of 40. According to the Center for Disease Control there were about 900 cases reported between 1988 and 2006; averaging around 50 cases each year. The Florida Department of Health reported 32 cases of Vibrio infections within Florida in 2014 with 7 of these begin fatal. Five of the cases were in the Florida panhandle but none were fatal. So far this year in Florida there have been 11 cases statewide, 5 of those fatal. Only 1 case was in the panhandle and it was nonfatal. Though 43 cases and 12 fatalities over the last two years in Florida are reasons for concern, when compared to the number of humans who enter marine and brackish water systems every day across the state, the numbers are quite low.

What are the symptoms of Vibrio infection?

For healthy people who consume Vibrio containing shellfish symptoms could include vomiting, diarrhea, and abdominal pain. Wounds exposed to seawater that become infected will show redness and swelling. For the at-risk populations described above the bacteria will enter the bloodstream and rapidly cause fever and chills, decreased blood pressure, and blistering skin lesions. For these at-risk population 50% of the cases are fatal and death generally occurs within 48 hours.

It is important that anyone who believes they are at high risk and have the above symptoms that they seek medical attention as quickly as possible.

How can I protect myself from Vibrio infection?

We recommend anyone who has a chronic liver condition, hemochromatosis, or any other immune suppressing medical condition, not consume raw or undercooked filter-feeding shellfish and not enter the water if they have an open wound.

The Center of Disease Control recommends

- If harvesting or purchasing uncooked shellfish do not consume any whose shells are already open

- Keep all shellfish on ice and drain melted ice

- If steaming, do so until the shell opens and then for 9 more minutes

- If frying, do so for 10 minutes at 375°F

- Avoid foods served, and has had contact with, raw or poorly cooked shellfish or that has had contact with raw shellfish juice

- If shucking oysters at a fish house or restaurant, wear protective gloves

It is also important to know that the bacteria does NOT change the appearance or odor of the shellfish product, so you cannot tell by looking at them whether they are good or bad.

For more information on this bacteria visit:

http://www.floridahealth.gov/diseases-and-conditions/vibrio-infections/vibrio-vulnificus/

http://www.cdc.gov/vibrio/vibriov.html

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 20, 2015

This past week hundreds of dead fish washed ashore between Escambia and Okaloosa counties. Most were of one species but there were others who died and it appeared they had been in the water for quite a while. Determining the cause of fish kill can be tricky. You can observe how many different species were involved, and how many of each species. You can also review changes in the biological and chemical environment of the water system impacted. Fish kills occur for a variety of reasons but many are connected to either a decline in dissolved oxygen, the presence of red tide, or some pathogen that may be affecting the fish.

Dead fish near Ft. Pickens in Pensacola. Photo: Rick O’Connor

Excessive nutrients, many times associated with heavy rain, can trigger algal blooms that can eventually lower the concentration of dissolved oxygen; however high water temperatures can do the same. When dissolved oxygen levels drop below 4.0 mg/L most fish are stressed, and most fish leave. Some fish however are very sensitive to these changes and die, menhaden are one of them. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission listed menhaden as one of the species found on the beach but there were others as well, actually the majority were scaled sardines. The Florida Department of Environmental Protection monitors dissolved oxygen at the beach each week and their data indicated no problems prior to the kill. The Escambia County Division of Marine Resources measured the dissolved oxygen after the kill and found levels to be normal. Some would point to the abundant amount of green algae, “June grass”, as a sign of an algal bloom but mass amounts of June grass appear each summer and fish kills typically do not follow them.

Red tides are blooms of a particular microscopic single celled creature called Karenia brevis. When these photosynthetic protist are disturbed they can release a toxin which dissipates through the water and can become part of the aersols produced by waves. Many species of fish and marine mammals struggle with red tides and mortality due these outbreaks are common. Records of red tide blooms go back as far as the early colonial period and have been part of Florida for centuries. They typically form offshore and move inland with the wind and currents. Once they reach shallow waters human released nutrients can increase populations of K. brevis and enhance the problems they cause. They are more common in southwest Florida but do occur in the panhandle. Agencies along the Gulf coast monitor for red tide outbreaks each week. The Escambia County Division of Marine Resources does so here and found no traces of K. brevis before or after the kill.

As far as pathogens, or another possible cause, we are not sure. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has officially listed the cause as “unknown”. Fish kill data in Escambia County shows changes over the years. In the 1970’s there were a fewer fish kills reported each year but each kill involved hundreds of thousands of fish, many times menhaden. Today there are more fish kills reported but many of these reports are a single fish or fewer than 10. This is the first large number kill we have had in a while. Escambia County Sea Grant reports water quality information, including fish kills and red tides, for the Pensacola Bay area each week on their website (http://escambia.ifas.ufl.edu). Fish kill information for the state of Florida can be found at http://myfwc.com/research/saltwater/health/fish-kills-hotline/. If you have any questions about local fish kills contact Sea Grant at your local county extension office.

by Rick O'Connor | May 15, 2015

Following a previous article on the number of ways you can help sea turtles, this week we will look at ways that local residents can help keep our waterways clean. Poor water quality is a concern all over the country, and so it is locally as well. When we have heavy rain all sorts of products wash off into streams, rivers, bays, and bayous. The amount and impact of these products vary but most environmental scientists will agree that one of biggest problems is excessive nutrients.

Marine science students monitoring nutrient levels in a local waterway. Photo: Ed Bauer

Nutrient runoff comes in many forms. Most think of fertilizers we use on our lawns but it also includes grass clippings, leaf litter, and animal waste. These organic products contain nitrogen and phosphorus which, in excess, can trigger algal blooms in the bay. These algal blooms could contain toxic forms of microscopic plants that cause red tide but more often they are nontoxic and cause the water to become turbid (murky) which can reduce sunlight reaching the bottom, stressing seagrasses. When these algal blooms eventually die they are consumed by bacteria which require oxygen to complete the process. This can cause the dissolved oxygen concentrations to drop low enough to trigger fish kills. This process is called eutrophication. In addition to this, animal waste from birds and mammals contain fecal coliform bacteria. These bacteria are used as indicators of animal waste levels and can be high enough to require health advisories to be issued.

So what we can do about this?

- We can start with landscaping with native plants to your area. Our barrier islands are xeric environments (desert-like). Most of our native plants can tolerate low levels of rain and high levels of salt spray. If used in your yard they will require less watering and fertilizing, which saves the homeowner money. It also reduces the amount of fertilizer that can reach the bay.

- If you choose to use nonnative plants you should have your soil tested to determine which fertilizer, and how much, should be applied. You can have your soil tested at your county Extension Office for a small fee. Knowing your soil composition will ensure that the correct fertilizer, and the correct amount, will be used. Again, this reduces the amount reaching the bay and saving the home owner money.

- Where ever water is discharged into the bay you can plant what is called a Living Shoreline. A Living Shoreline is a buffer of native marsh grasses that can consume the nutrients before they reach the bay and also reducing the amount of sediment that washes off as well, reducing the turbidity problem many of our seagrasses are facing.

These three practices will help reduce nutrient runoff. In addition to lowering the nutrient level in the bays it will also reduce the amount of freshwater that enters. Decrease salinity and increase turbidity may be the cause of the decline of several species once common here; such as scallops and horseshoe crabs. Florida Sea Grant is currently working with local volunteers to monitor terrapins, horseshoe crabs, and scallops in Escambia and Santa Rosa counties. We are also posting weekly water quality data on our website every weekend. You can find each week’s numbers at http://escambia.ifas.ufl.edu. If you have any questions about soil testing, landscaping, living shorelines, or wildlife monitoring contact Rick O’Connor at roc1@ufl.edu. Help us improve water quality in our local waters.