by Erik Lovestrand | Aug 27, 2021

It seems like there has always been a soft spot in my heart for snakes. From a young age, I was fascinated with all reptiles. The rural fabric of where I grew up in Central Florida (think late-1960s) afforded many opportunities for us kids to roam the woods and fields in search of adventure during summer vacation. I vividly remember the occasional eastern hognose snake that we would catch as kids. They were easy to house for a while, as there was no shortage of toads for a food source. This article will focus on some of the common species of snakes in NW Florida and a couple of snake safety tips.

Very likely, one of the first species of snakes most people encounter in North Florida is the gray rat snake (aka oak snake). If you raise chickens, you can greatly reduce the time it takes to enjoy your first encounter. I pull oak snakes out of our nest boxes on a regular basis. I have also encountered some rather large pine snakes in this manner; one with eight egg lumps in its mid-section. These are both harmless, beautiful creatures that can unfortunately make you hurt yourself in a dimly lit coop as you reach in to collect eggs. Another commonly encountered snake in our area is the corn snake, also called a red rat snake. The orange background and dark-red blotches make this one of our most beautiful species. Southern black racers are also a commonly seen species due to their daytime hunting habits. Racers are black on the back with a white chin and very slender for their length. They live up to their name and can disappear in a flash when startled. Two other species regularly encountered here are in the “garter snake” group. The eastern garter snake is one of very few species in our area with longitudinal stripes. They can have a tan to yellowish background color or even a greenish or blue color. The closely related ribbon snake looks similar in color and pattern but has a much slimmer build.

Gray rat snakes are also called oak snakes and are quite common in North Florida

My home county of Wakulla is home to four species of venomous snakes, which include the eastern diamondback rattlesnake, pygmy rattlesnake, coral snake and Florida cottonmouth. However, if you live in other parts of North Florida, you may have five or possibly even six species that are venomous. The copperhead’s range extends into North Florida in a few Counties along the Apalachicola River and the canebrake (or timber) rattlesnake ranges slightly farther south in the peninsula to North-Central Florida. I’ve only seen one canebrake rattlesnake and it was crossing a road on the north side of Gainesville many years ago. Both pygmy rattlers and cottonmouths can be very abundant locally in the right habitats but diamondbacks and coral snakes are less common these days having lost much of their preferred habitats to development.

My best advice for those worried about being bitten by a snake is don’t try to pick one up, and watch where you put your hands and feet. It really is relatively easy to avoid (key word here is avoid) being bitten by a snake. There are many good medical sites on the web with detailed recommendations for snakebite treatment. In the very rare circumstance when someone is envenomated, the best policy is to remain as calm as possible and head for medical attention. Do not cut the skin and try to suck out the venom or apply a tourniquet. These strategies generally cause more harm than good.

I always appreciate the chance to get a look at one of our incredible native snakes when afield, especially if it happens to be one of our venomous species. A big diamondback rattlesnake is an impressive animal to happen on when afield. This appreciation does not mean that I don’t get startled occasionally when surprised, but once that instinctive reaction passes, I can truly appreciate the beauty of these scaly critters.

by Molly Jameson | Aug 12, 2021

Article by Rachel Mathes, Horticulture Program Assistant with UF/IFAS Extension Leon County.

By Rachel Mathes

My only brother and his family live in Appleton, Wisconsin. Though I’m only able to see my niece and nephews one or two times a year, we have a deep connection through our love of the outdoors.

Zach discovering the joy of nature. Photo by Rachel Mathes.

Their middle son, Zachary, is a budding naturalist at just four years old. When I visit them, Zach, his brother Connor, sister Cecilia, and I, load up the wagon and go for walks on the edge of the prairie in their neighborhood. We start our walks looking for scat and signs of wildlife. Because the kids are so close to the ground, they often spot wildlife trails before I do. We talk about what animals may be there, what they eat, and how we can help them.

After each walk, we wind down at home with an iNaturalist session. Zach and his siblings help me choose what animal or plant we think we saw with the help of the app’s nearby suggestions tool. A favorite game we play after all our photos are entered into the app is a game we’ve coined, “where’s that animal?” We use the iNaturalist explore feature to find sightings of exciting creatures like wolves and beavers near their home. The kids have learned that even scientists often don’t see the animals they study, just signs of them.

At age three, Zach learned to identify milkweed with impressive accuracy. I pointed out the plant on a previous trip more than six months earlier and he remembered how to find them. Common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca, is a large leafed species that prefers winters a bit colder than we get here in the Florida Panhandle, but is native in northern states across the Eastern US, including Wisconsin. Zach is often stopping the wagon to scout for monarch caterpillars, finding even the smallest instars and eggs.

Zach learned to identify common milkweed, Asclepias syriaca, at the age of three. Photo by Rachel Mathes.

When I video call the kids from Florida, Zach is often asking to see my fruit trees, vines, and bushes. He knows that we have very different seasons than Wisconsin when I am eating blueberries in May and he’s still knocking frost off his snow boots. In July, he tells me about the raspberries they find in the woods with their dad. We both get a bit of seasonal berry jealousy. On my last trip we planted thornless blackberries in their garden together. It remains to be seen whether the birds will let the kids have a harvest, but the kids will be excited either way.

Though we may live a thousand miles apart, I know my relationship with my niece and nephews will continue to thrive as they explore the natural world around them. One day, I hope to introduce them to the awe of Florida manatees and alligators. Until then, I will relish the time we get to spend together outdoors in nature and on the phone together. I know that Zachary and his siblings will grow up having respect for the natural world and I hope he always exclaims, “Monarch! Look auntie Rachel, a monarch caterpillar!” on our walks together.

Author: Rachel Mathes, Horticulture Program Assistant with UF/IFAS Extension Leon County.

by Mark Mauldin | Apr 9, 2021

Spring can be a busy time of year for those of us who are interested in improving wildlife habitat on the property we own/manage. Spring is when we start many efforts that will pay-off in the fall. If you are a weekend warrior land manager like me there is always more to do than there are available Saturdays to get it done. The following comments are simple reminders about some habitat management activities that should be moving to the top of your to-do list this time of year.

Aquatic Weed Management – If you had problematic weeds in you pond last summer, chances are you will have them again this summer. NOW (spring) is the time to start controlling aquatic weeds. The later into the summer you wait the worse the weeds will get and the more difficult they will be to control. The risk of a fish-kill associated with aquatic weed control also increases as water temperatures and the total biomass of the weeds go up. Springtime is “Just Right” for Using Aquatic Herbicides

Cogongrass Control – Spring is actually the second-best time of year to treat cogongrass, fall (late September until first frost) is the BEST time. That said, ideally cogongrass will be treated with herbicide every six months, making spring and fall important. When treating spring regrowth make sure that there are green leaves at least one foot long before spraying. Spring is also an excellent time of year to identify cogongrass patches – the cottony, white blooms are easy to spot. Identify Cogongrass Now – Look for the Seedheads; Cogongrass – Now is the Best Time to Start Control

Cogongrass seedheads are easily spotted this time of year.

Photo credit: Mark Mauldin

Warm-Season Food Pots – There is a great deal of variation in when warm season food plots can be planted. Assuming warm-season plots will be panted in the same areas as cool-season plots, the simplest timing strategy is to simply wait for the cool-season plots to play out (a warm, dry May is normally the end of even the best cool-season plot) and then begin preparation for the warm-season plots. This transition period is the best time to deal with soil pH issues (get a soil test) and control weeds. Seed for many varieties of warm-season legumes (which should be the bulk of your plantings) can be somewhat hard to find, so start looking now. If you start early you can find what you want, and not just take whatever the feed store has. Warm Season Food Plots for White-tailed Deer

Deer Feeders – Per FWC regulations deer feeders need to be in continual operation for at least six months prior to hunting over them. Archery season in the Panhandle will start in mid-October, meaning deer feeders need to be up and running by mid-April to be legal to hunt opening morning. If you have plans to move or add feeders to your property, you’d better get to it pretty soon. FWC Feeding Game

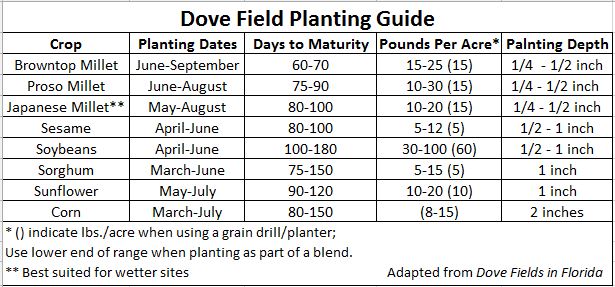

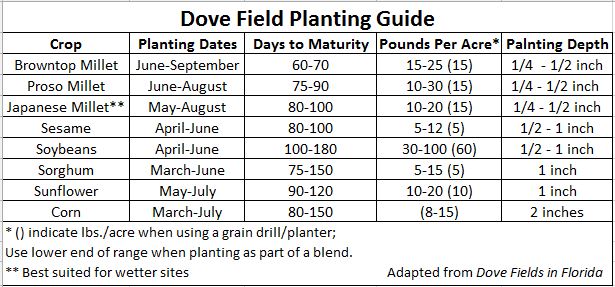

Dove Fields – The first phase of dove season will begin in late September. When you look at the “days to maturity” for the various crops in the chart below you might feel like you’ve got plenty of time. While that may be true, don’t forget that not only do you need time for the crop to mature, but also for seeds to begin to drop and birds to find them all before the first phase begins. Because doves are particularly fond of feeding on clean ground, controlling weeds is a worthwhile endeavor. If you are planting on “new ground”, applying a non-selective herbicide several weeks before you begin tillage is an important first step to a clean field, but it adds more time to the process. As mentioned above, it’s always pertinent to start sourcing seed well in advance of your desired planting date. Timing is Crucial for Successful Dove Fields

There are many other projects that may be more time sensitive than the ones listed above. These were just a few that have snuck up on me over the years. The links in each section will provide more detailed information on the topics. If you have questions about anything addressed in the article feel free to contact me or your county’s UF/IFAS Extension Natural Resource Agent.

by Sheila Dunning | Jan 28, 2021

Groundhog

Groundhog Day is celebrated every year on February 2, and in 2021, it falls on Tuesday. It’s a day when townsfolk in Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania, gather in Gobbler’s Knob to watch as an unsuspecting furry marmot is plucked from his burrow to predict the weather for the rest of the winter. If Phil does see his shadow (meaning the Sun is shining), winter will not end early, and we’ll have another 6 weeks left of it. If Phil doesn’t see his shadow (cloudy) we’ll have an early spring. Since Punxsutawney Phil first began prognosticating the weather back in 1887, he has predicted an early end to winter

only 18 times. However, his accuracy rate is only 39%. In the south, we call also defer to General Beauregard Lee in Atlanta, Georgia or Pardon Me Pete in Tampa, Florida.

But, what is a groundhog? Are gophers and groundhogs the same animal? Despite their similar appearances and burrowing habits, groundhogs and gophers don’t have a whole lot in common—they don’t even belong to the same family. For example, gophers belong to the family Geomyidae, a group that includes pocket gophers, kangaroo rats, and pocket mice. Groundhogs, meanwhile, are members of the Sciuridae (meaning shadow-tail) family and belong to the genus Marmota. Marmots are diurnal ground squirrels. There are 15 species of marmot, and groundhogs are one of them.

Science aside, there are plenty of other visible differences between the two animals. Gophers, for example, have hairless tails, protruding yellow or brownish teeth, and fur-lined cheek pockets for storing food—all traits that make them different from groundhogs. The feet of gophers are often pink, while groundhogs have brown or black feet. And while the tiny gopher tends to weigh around two or so pounds, groundhogs can grow to around 13 pounds.

While both types of rodent eat mostly vegetation, gophers prefer roots and tubers while groundhogs like vegetation and fruits. This means that the former animals rarely emerge from their burrows, while the latter are more commonly seen out and about. In the spring, gophers make what is called eskers, or winding mounds of soil. The southeastern pocket gopher, Geomys pinetis, is also known as the sandy-mounder in Florida.

Southeastern Pocket Gopher

The southeastern pocket gopher is tan to gray-brown in color. The feet and naked tail are light colored. The southeastern pocket gopher requires deep, well-drained sandy soils. It is most abundant in longleaf pine/turkey oak sandhill habitats, but it is also found in coastal strand, sand pine scrub, and upland hammock habitats.

Gophers dig extensive tunnel systems and are rarely seen on the surface. The average tunnel length is 145 feet (44 m) and at least one tunnel was followed for 525 feet (159 m). The soil gophers remove while digging their tunnels is pushed to the surface to form the characteristic rows of sand mounds. Mound building seems to be more intense during the cooler months, especially spring and fall, and slower in the summer. In the spring, pocket gophers push up 1-3 mounds per day. Based on mound construction, gophers seem to be more active at night and around dusk and dawn, but they may be active at any time of day.

Pocket Gopher Mounds

Many amphibians and reptiles use pocket gopher mounds as homes, including Florida’s unique mole skinks. The pocket gopher tunnels themselves serve as habitat for many unique invertebrates found nowhere else.

So, groundhogs for guesses on the arrival of spring. But, when the pocket gophers are making lots of mounds, spring is truly here. Happy Groundhog’s Day.

by Mark Mauldin | Oct 23, 2020

Archery season for white tailed deer opens this Saturday (10/24/20) in FWC Hunting Zone D (basically the Panhandle west of Tallahassee, see figure 1). Before you go hunting be sure that you have a plan in place for logging and reporting your harvest. Last year FWC implemented a mandatory harvest reporting system. That system is still in effect this year but with some modifications.

Figure 1. FWC Hunting Zone D

myfwc.com

The most notable change to the harvest reporting system this year is with the associated smart phone app. There is a new app this year – Fish|Hunt Florida. This new app will replace the Survey123 for ArcGIS app that was used last year.

In my opinion, the logging and reporting function on the Fish|Hunt Florida app is simpler to use than the previous app. Additionally the Fish|Hunt Florida app has many other useful features. A few highlights include; the ability to view and purchase hunting and fishing licenses/permits through the app, interactive versions of hunting and fishing regulations, and several other handy resources for sportsmen including, marine forecasts, tides, wildlife feeding times, sunrise & sunset times, boat ramp locator and a current location feature. Screenshots from the app are included below. The Fish|Hunt Florida app is available for free through the Apple App Store and the Google Play Store.

Remember, the current regulations state that your deer harvest must be logged before the animal is moved. Take a minute or two to install the app on your phone before you go hunting. Using the app allows logging and reporting to happen simultaneously. The app can be used for logging and reporting a harvest even in areas where cell service is poor. Harvest information will can be saved and the app will automatically complete the process as soon as adequate cell service is available. The alternative to using the app is a two-step process, the harvest can be logged (prior to being moved) on a paper form and then reported by calling 888-HUNT-FLORIDA (888-486-8356) or going to GoOutdoorsFlorida.com within 24 hours.

Follow the link for specific instructions for logging and reporting a harvested deer using the Fish|Hunt Florida app; don’t worry, it’s easy. Fish|Hunt Florida app instructions

For more information on the Fish|Hunt Florida app and the FWC Deer Harvest Reporting System visit myfwc.com.

Screenshot of the Boat Info tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Fishing Tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Home screen from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

Screenshot of the Hunting tab from the Hunt|Fish Florida App. Click on the image to make it larger.

by Rick O'Connor | Oct 21, 2020

It’s Halloween…

The time of year we think of werewolves, warlocks, witches, and full moon evenings. But there is another creature who likes to howl at the moon this time of year – the coyote.

A coyote moving on Pensacola Beach near dawn.

Photo provided by Shelley Johnson.

Actually, coyotes howl all throughout the year, and they are not specifically howling at the moon. The name “coyote” is a Native American term meaning “singing dog”, or “barking dog”. They are famous for their early evening and early morning calls. Howls, barks, yelps, and yaps are very familiar to those living out west – and now for those living in the eastern United States.

It is believed the animal originated in the grasslands and deserts of the American southwest feeding on a variety of rodents. They have successfully dispersed across the country and can now be found in almost any habitat in the continental United States – including barrier islands. Though they owe much of their success to their ability to adapt to different foods and habitats, they also owe some of their success to humans. We have reduced their primary predators – bears, wolves, and mountain lions – to a level where they could move around more safely. There have been efforts to restore these predator populations in some localized areas of the U.S., but those are localized, and the process has been slow. All the while the coyote has enjoyed a more predator free world.

They are also opportunistic feeders. Though the bulk of their diet are small rodents, they are known to eat small birds, reptiles, amphibians, rabbits, squirrels, and even fruit. Out west, working in teams, they can take down larger prey – such as deer, and can do so here in the east as well. But their large prey targets are usually smaller members of the herd, sick, or old ones. They have also learned to feed on road kills of these animals.

Then there are humans. We provide an abundance of garbage which they have learned to scavenge through. Pet food left outside, gardens with produce, small livestock, and even pet cats and small dogs have been added to their menu. We have made their world much better.

With their numbers increasing in human populated areas, like Santa Rosa Island, people are becoming a bit nervous around them. The image of the toothed predator howling at the harvest moon on Halloween night in a pack with others makes us a bit uneasy. So, how dangerous are they?

Not very.

Coyotes are intelligent animals, and though they have learned to live and hunt within our neighborhoods, they are still afraid of us – they consider us trouble. On a recent trip to Colorado I was hiking down a trail and saw what appeared to be two sets of pointed ears in the grass. My guess was coyote but was not sure – so I began to walk towards them. Three coyotes immediately got up and moved off across the next ridge. They wanted nothing to do with me. And that is how it should be.

Those on barrier islands, like Santa Rosa, are no different. They are more active at dawn and dusk (crepuscular) and spend their days and late nights in a den somewhere. Occasionally people will see them in the middle of the day, or hear a yelp or howl around 2:00 AM, but it is more of a sunrise and sunset deal for them. They can remain motionless and undetected when people are around and will often run if we get too close. Many are not sure whether they are seeing a coyote or a German shepherd when they see one, both being about the same size. Coyotes tend to run with their tails down, unlike dogs and wolves who prefer to run with their tails up.

All of this said, there have been attacks on people – mostly out west and in southern California in particular. In most cases, the animals have either intentionally or unintentionally been fed by people. When this happens, they lose their fear of us and return for another easy meal. They are wild animals and being cornered by people or dogs (intentionally or unintentionally) can lead to defensive behaviors that could include attacks. To avoid this, we should not approach any coyote. Keep your trash secured and in cans that would be difficult for coyotes to access. Bring your pet food in at night and do not let pet cats and small dogs out in the evenings without supervision.

Bad encounters with these howling animals are rare, and with a little education and behavior changes on our part, should remain so.

Happy Halloween.