by hollyober | Mar 20, 2019

A prescribed fire burns safely in a natural area. Photo by Holly Ober.

Most plant and wildlife communities in Florida are adapted to periodic fires. For thousands of years, fires were ignited naturally, and frequently, by lightning. In fact, Florida has the greatest number of lightning strikes of any state in the country. About 1,000 lightning-set fires are documented in Florida each year.

Today, due to the many people living in Florida, the vast majority of fires naturally ignited by lightning are quickly suppressed by trained personnel. This is done to reduce the loss of human life and property. Although helpful to human safety in the short term, suppression of fire from natural areas for long periods of time can be problematic for all the native plant communities and wildlife that are adapted to periodic fire, and ultimately dangerous for humans as well. The longer our natural areas go unburned, the greater the accumulation of vegetative material that could serve as fuel for fire, and the greater the possibility of uncontrollable wildfires devastating natural areas, homes, and buildings when lightning strikes.

PRESCRIBED FIRES are an important tool: they are a safe alternative to wildfires. Prescribed fires are intentionally set under favorable weather conditions with the goal of stimulating the ecological benefits produced by natural wildfires. By selecting safe conditions for these burns and by preparing for them in advance by creating barriers to halt the spread of fire past desired borders, trained personnel have much more control over the results of these fires. The reason we often see and smell smoke in the spring is because this is the most popular time of year to use prescribed burning as a forest management tool.

Below are some of the benefits fire provides to the health of the many plants and wildlife that naturally occur in our state.

- Fire maintains required habitat conditions for many of Florida’s plant and wildlife species.

- Fire promotes fruit production of many woody plant species.

- Fire promotes flowering of herbaceous (non-woody) plant species.

- Fire promotes diverse herbaceous plants that serve as food for insects and wildlife.

- Fire scarifies seeds, breaking down their hard seed coats and promoting germination.

- Fire prepares sites for seeding or planting of species that require bare mineral soil.

- Fire creates growing conditions required by some cone-bearing trees. It reduces leaf litter on the soil surface, increases nutrient reserves, and canopy openings so that sunlight can reach the forest floor.

- Fire releases nutrients bound up in dead organic matter, ultimately increasing palatability, digestibility, and nutritional value of growing plants for wildlife.

- Fire can improve the quality of forage for grazing livestock.

- Fire changes the density of trees in the forest, creating space for some wildlife species.

- Fire removes hardwood thickets and vines in the understory of pine forests, making these areas more suitable for some wildlife species.

- Fire controls insect pests and diseases that afflict pine trees.

- Fire increases the rate of nutrient cycling of some elements and elevates soil pH.

- Fire creates a diverse habitat conditions when fires are patchy, leaving pockets of unburned areas.

- Fire reduces the risk of severe, high intensity wildfires that could cause harm to native plants and wildlife by preventing the accumulation of highly-flammable, dead vegetation.

The last week in January has been designated as Prescribed Fire Awareness Week in Florida. Early February has been designated as Prescribed Fire Awareness Week in Georgia. March is Prescribed Fire Awareness Month in South Carolina. Why are so many southern states making a big deal about prescribed fire? It is because we have recognized the importance of safe fires for both the health of our native plants and wildlife as well as the safety of our human residents and visitors. If you see or smell smoke in a nearby natural area, it might well be coming from a prescribed fire intended to benefit our natural plants and wildlife as well as our safety.

To learn more about prescribed burning in Florida, visit https://www.freshfromflorida.com/Divisions-Offices/Florida-Forest-Service/Wildland-Fire/Prescribed-Fire

by Andrea Albertin | Mar 20, 2019

By Vance Crain and Andrea Albertin

Fisherman with a large Shoal Bass in the Apalachicola-Chattahootchee-Flint River Basin. Photo credit: S. Sammons

Along the Chipola River in Florida’s Panhandle, farmers are doing their part to protect critical Shoal Bass habitat by implementing agricultural Best Management Practices (BMPs) that reduce sediment and nutrient runoff, and help conserve water.

Florida’s Shoal Bass

Lurking in the clear spring-fed Chipola River among limerock shoals and eel grass, is a predatory powerhouse, perfectly camouflaged in green and olive with tiger stripes along its body. The Shoal Bass (a species of Black Bass) tips the scale at just under 6 lbs. But what it lacks in size, it makes up for in power. Unlike any other bass, and found nowhere else in Florida, anglers travel long distances for a chance to pursue it. Floating along the swift current, rocks, and shoals will make you feel like you’ve been transported hundreds of miles away to the Georgia Piedmont, and it’s only the Live Oaks and palms overhanging the river that remind you that you’re still in Florida, and in a truly unique place.

Native to only one river basin in the world, the Apalachicola-Chattahoochee-Flint (ACF) River Basin, habitat loss is putting this species at risk. The Shoal Bass is a fluvial specialist, which means it can only survive in flowing water. Dams and reservoirs have eliminated habitat and isolated populations. Sediment runoff into waterways smothers habitat and prevents the species from reproducing.

In the Chipola River, the population is stable but its range is limited. Some of the most robust Shoal Bass numbers are found in a 6.5-mile section between the Peacock Bridge and Johnny Boy boat ramp. The Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission has turned this section into a Shoal Bass catch and release only zone to protect the population. However, impacts from agricultural production and ranching, like erosion and nutrient runoff can degrade the habitat needed for the Shoal Bass to spawn.

Preferred Shoal Bass habitat, a shoal in the Chipola River. Photo credit: V. Crain

Shoal Bass habitat conservation and BMPs

In 2010, the Southeast Aquatic Resources Partnership (SARP), the National Fish and Wildlife Foundation and a group of scientists (the Black Bass Committee) developed the Native Black Bass Initiative. The goal of the initiative is to increase research and the protection of three Black Bass species native to the Southeast, including the Shoal Bass. It also defined the Shoal Bass as a keystone species, meaning protection of this apex predators’ habitat benefits a host of other threatened and endangered species.

Along the Chipola River, farmers are teaming up with SARP and other partners to protect Shoal Bass habitat and improve farming operations through BMP implementation. A major goal is to protect the river’s riparian zones (the areas along the borders). When healthy, these areas act like sponges by absorbing nutrients and sediment runoff. Livestock often degrade riparian zones by trampling vegetation and destroying the streambank when they go down to a river to drink. Farmers are installing alternative water supplies, like water wells and troughs in fields, and fencing out cattle from waterways to protect these buffer areas and improve water quality. Row crop farmers are helping conserve water in the river basin by using advanced irrigation technologies like soil moisture sensors to better inform irrigation scheduling and variable rate irrigation to increase irrigation efficiency. Cost-share funding from SARP, the USDA-NRCS and FDACS provide resources and technical expertise for farmers to implement these BMPs.

Holstein drinking from a water trough in the field, instead of going down to the river to get water which can cause erosion and problems with water quality. Photo credit: V. Crain

By working together in the Chipola River Basin, farmers, fisheries scientists and resource managers are helping ensure that critical habitat for Shoal Bass remains healthy. Not only is this important for the species and resource, but it will ensure that future generations can continue to enjoy this unique river and seeing one of these fish. So the next time you catch a Shoal Bass, thank a farmer.

For more information about BMPs and cost-share opportunities available for farmers and ranchers, contact your local FDACS field technician: https://www.freshfromflorida.com/Divisions-Offices/Agricultural-Water-Policy/Organization-Staff and NRCS field office USDA-NRCS field office: https://www.nrcs.usda.gov/wps/portal/nrcs/main/fl/contact/local/ For questions regarding the Native Black Bass Initiative or Shoal Bass habitat conservation, contact Vance Crain at vance@southeastaquatics.net

Vance Crain is the Native Black Bass Initiative Coordinator for the Southeast Aquatic Resource Partnership (SARP).

by Jennifer Bearden | Jan 31, 2019

This time of year in Northwest Florida, deer hunters are busy talking about the rut! What’s the rut, you might ask? Simply put, it’s deer breeding season. Deer hunters speculate on peak rut times each year. There are even peak rut forecasts. Why are hunters interested in deer rut? Hunters know that bucks are more active and careless during the rut.

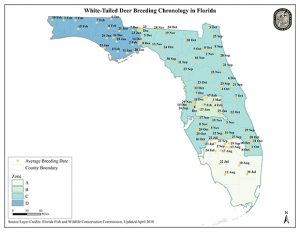

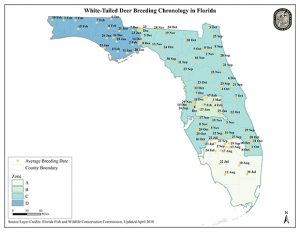

Deer Breeding Chronology in Florida May 2018. Source Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission

Bucks exhibit four rut behaviors: sparring, rubbing, scraping, and chasing. Sparring happens between bucks to establish dominance. This happens during the pre-rut. Dominant bucks are generally the ones who get the does. Bucks also make rubs on trees during the pre-rut period. They start this behavior to remove velvet from their antlers. They continue rubbing to mark their territory with their scent. Scraping is another way they mark their area. A scrape normally occurs under a low hanging branch. The buck will lick or chew on the branch while scraping the ground as well as urinating on the ground. The last rut behavior is chasing does. Does typically won’t be game for this unless they are ready to breed.

In other parts of the country, the rut is long over. Even in other parts of Florida, it is over. Florida has more variability in rut timing than in any other state. In Florida, deer rut starts in July in the southern part of the state and runs through February in the north. Deer breeding dates are more predictable in the northern U.S. where winters are too harsh for fawn survival. Deer breeding in our state is more variable because of our mild winters. Average breeding dates in Northwest Florida are very late compared to other parts of the country and the state. Our average breeding dates generally range from December to mid-February. Gestation takes about 200 days, so this puts fawning dates in late June through early September.

Even though we have average breeding dates for our area, these aren’t “magical dates”. Not all does go into estrus on the same day or even the same week.

8 point buck taken in Northwest Florida in January while chasing a doe. Photo credit: Jennifer Bearden

Estrus only lasts 24 hours and not all does become pregnant during the first estrus period. This means that about 28 days later does go into a second estrus. So the rut period is a range around the average date.

So, to all my fellow hunters in Northwest Florida, enjoy the 2019 rut! I know I have enjoyed watching several bucks chase does as well as having the opportunity to take the biggest buck of my life this January. Good luck to you all in your hunting ventures!

More information about the Florida Fish and Wildlife Commission Deer Breeding Chronology Study can be found at https://myfwc.com/hunting/deer/.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 31, 2019

As we begin our wildlife series for 2019, we will start with a snake that almost everyone has encountered but knows little about – the southern black racer.

The southern black racer differs from other black snakes in its brilliant white chin and thin sleek body.

Photo: Jacqui Berger.

This snake is common for many reasons.

- It is found throughout the eastern United States

- It is diurnal, meaning active during daylight hours when we are out and about

- It can be found in a variety of habitats and is particularly fond of “edge” areas between forest and open habitat – they do very well around humans.

The southern black racer (Coluber constrictor priapus) is one of eight subspecies of this snake found in the United States. This local variety is a beautiful shiny black. The shine is due to the fact that they have smooth, rather than keeled, scales. It is a long snake, reaching up to six feet, but very thin – and very fast! Most of us see it just before it darts away.

They are sometimes confused with the cottonmouth. It can be distinguished in having a long “thin” body, as compared to the cottonmouths shorter “thick” body. It has a brilliant white chin and the top of the head is solid black. Cottonmouths can be mottled, usually have a cream-colored chin with a dark “mask” extending from the lower point of the chin through the eye. Cottonmouths also have the wide delta shaped head compared the finger-shaped head of the racer. They are also confused with the eastern indigo snake. The indigo is very long (up to eight feet) large bodied snake, and the lower chin is a reddish-orange color. The coachwhip is a close cousin of the racer, found in many of the same habitats. It has a similar body shape, and speed, but is a light tan color with a dark brown-black head and neck.

The juvenile black racer looks more like a corn snake, and is sometimes confused with a pygmy rattler.

Photo: C. Kelly

The juvenile looks nothing like the adult. The young racers hatch from rough covered eggs laid in late winter and early spring. They typically lay between 6-20 eggs and hide them under rocks, boards, bark, and even in openings in the side of homes. In late spring and early summer, they hatch. Their body resembles adults, but their coloration is a mottled mix of grays, browns, and reds – having distinct patches on their backs. This helps with camouflage but often they are mistaken for pygmy rattlesnakes and are killed.

They are great climbers and are found in our shrubs and trees, as well as on our houses and in our garages. Though sometimes confused with the cottonmouth, this snake is non-venomous and harmless. Harmless in the sense that a bite from will cause no harm – but it will bite. Black racers are notorious for this. If approached, it generally freezes first – to avoid detection. If it believes it has been detected, it will flee at amazing speeds. If it cannot flee, it will turn and bite… repeatedly. Again, the bites are harmless, but could draw blood. Cleaning with soap and water is all you need.

They are opportunistic feeders hunting a variety of prey including small mammals, reptiles, birds, insects, and eggs. They also hunt snakes, including small venomous species. Unlike the larger venomous snakes, black racers stalk their prey – many times with their heads raised similar to cobras. When prey is detected, they spring on them with lighting speed. Despite the scientific name “constrictor”, they do not constrict their prey, rather pin it down and wait for it to suffocate.

They do have their predators, particularly hawks. When approached they will first freeze to avoid detection, they may release a foul-smelling musk as a warning, and sometimes will vibrate their tails. In leaf-litter, this can sound very similar to a rattlesnake – not helping with the juvenile identification confusion. One paper reported finding a dead great horned owl with a black racer in its talons. Apparently, the owl grabbed the snake too far back. It killed the snake but not before the snake was able to strangle the owl.

They are hibernating this time of year but will soon be laying another clutch of eggs and we will once again encounter this most common of snakes.

References

Florida Museum of Natural History. Southern Black Racer (Coluber constrictor priapus). http://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/herpetology/fl-snakes/list/coluber-constrictor-priapus/.

Gibbons, W., M/ Dorcas. 2005. Snakes of the Southeast. University of Georgia Press, Athens GA. pp. 253.

Perry, R.W., R.E. Brown, D.C. Rudolph. 2001. Mutual Mortality of a Great Horned Owl and a Southern Black Racer: a Potential Risk for Raptors Preying on Snakes. The Willson Bulletin, 113(3). http://doi.org/10.1676/0043-5643(2001)113[0345:MMOGH0]2.0.CO;2.

Willson, J.D. Species Profile: Black Racer (Coluber constrictor priapus). SREL Herpetology. www.srelherp.uga.edu/snakes/colcon.htm.

by Erik Lovestrand | Nov 26, 2018

This beautiful scarlet kingsnake was run over near the author’s home

Snakes are some of the coolest animals on the planet but I’ll admit to something right up front; when a snake surprises me, I still jump, often. Even if I seem composed on the outside, something inside me almost always jumps. It does not matter if it is a venomous species or not. In spite of my basic understanding of and great appreciation for reptiles, snakes connect with a primal instinct that shouts “lookout” at some subconscious level. This human character trait is most-often the undoing of many an innocent serpent, happily going about its business when, WHAM, lights out. When a snake dares touch the human subconscious, our first emotion is often shock or fear; then perhaps anger; and in the end, payback for the offense. Many a good snake has met a very bad end when it has surprised a person.

Shock and fear are powerful emotions and I can almost (not totally) understand the outcome described above when someone is honestly shocked by a snake’s unexpected appearance. Nevertheless, even my wife, during a shocking encounter with a 5-foot oak snake while collecting eggs in the chicken house, was able gather her wits and shoo the critter out of the coop with a stick, rather than kill it. She did have me go the next evening to get the eggs though.

The one thing I have no empathy for however is when folks go out of their way to kill a snake that is trying to cross one of our roadways. About 90% of the dead snakes I see on the road are so close to the edge of the pavement that they were easily avoidable. C’mon people, that should be a “snake-safe” zone. These animals are likely never to encounter a human as they go about their business, performing important ecological functions in their natural habitat. Their great misfortune was that they had to cross an asphalt corridor used by humans. How about providing the same courtesy that most folks do when they see a turtle on the highway.

I see my share of cottonmouths smashed on the road (and that’s a shame too in my book) but other flattened species I’ve encountered include mud snakes, rat snakes, garter snakes, ribbon snakes, water snakes, racers, scarlet kingsnakes, green snakes, and many more; all harmless creatures. Recently, I stopped to look at a nice 4-foot coachwhip; a beautiful specimen, except for the fact that it was dead.

I get a thrill in seeing a living snake and having the chance to marvel at its form, function and beauty. If you ever have the chance to look closely at a pygmy rattlesnake in the wild (hopefully not in your turkey blind) you will be blown-away by its magnificent beauty. Black, velvety blotches on a gray background, with a rusty stripe running down the middle of its back. Same thing for a large diamondback rattlesnake (from a respectable distance). These have been some of my favorite natural encounters in the woods of North Florida, where we are truly blessed with a diversity of amazing animals and yes, super-amazing snakes. We should always use common sense of course when roaming the woods and enjoying our wild encounters, i.e. don’t ever catch venomous snakes (not worth the thrill), keep your hands out of hidden places, and watch where you put your feet. Oh, and work on cultivating a “live and let live” attitude when it comes to our scaly friends on the highway. They will oblige likewise.

by hollyober | Nov 9, 2018

The week prior to Halloween is officially designated as National Bat Week. In honor of this event, it’s worth considering some of the benefits bats provide to us.

Did you know there is a species of bat that lives nowhere in the world but within our state? It’s called the Florida Bonneted Bat, and occurs in only about 12-15 counties in south and central FL. These bats are so mysterious that we’re currently not even sure exactly where they occur. They are so rare that they’re listed as a federally endangered species.

The Florida Bonneted Bat lives nowhere in the world but Florida. Photo credits: Merlin Tuttle.

These bats were named for their forward-leaning ears, which they can tilt forward to cover their eyes. With a wingspan of 20 inches, they are the largest bats east of the Mississippi River: only two U.S. species are larger than they are, and these both occur out west.

We have been investigating the diet of Florida Bonneted Bats. To do this, we captured bats in specialized nets, and then collected their scat (called guano). Next, we processed the scat in a laboratory using DNA metabarcoding to determine which insect species the bats had recently consumed.

We found that the bats eat several economically important insects, including the following:

- fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda)

- lesser cornstalk borer (Elasmopalpus lignosellus)

- tobacco hornworm (Manduca sexta)

- black cutworm (Agrotis ipsilon)

These insects are pests of corn, cotton, peanut, soybean, sorghum, tobacco, tomato, potato, and many other crops.

Furthermore, the bats did not eat these insect pests infrequently. In fact, 86% of the samples we examined contained at least one pest species. On average, each sample contained three pest species! This tells us that Florida Bonneted Bats should be considered IPM (Integrated Pest Management) agents.

Currently, a new student has begun investigating the diets of bats more commonly found in northern Florida, southern Georgia, and southern Alabama. By the time Bat Week 2019 rolls around we’ll have details on which insect pests these bats could eat on your property.

If you’re interested in helping bats or incorporating them into your Integrated Pest Management efforts, consider creating roosts for them (places where the bats can sleep during the day). Bats roost not only in caves, but also in cavities in trees, in dead palm fronds, and in bat houses.