by Rick O'Connor | Jan 27, 2017

After Hurricane Ivan devastated the Pensacola area in 2004, my son was working to repair docks in local waterways. One day, after working on a project in Bayou Texar (near Pensacola Bay), he came by our house and said that he had seen a bald eagle fly over. My wife and I both responded with amazement but at the same time were thinking… “Yea right”. A few days later, we were sitting on the back porch (we live near Bayou Texar) and glancing up we saw a huge bird flying over… you guessed it… a bald eagle. We both looked at each other and just shook our heads saying “did you just see?… yep, that was a bald eagle”. It was totally cool!

An adult and juvenile bald eagle on nest in Montana.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

In the 1970’s I worked for a local chemical plant on Escambia Bay that had a bird sanctuary on the property. Occasionally a bald eagle would appear during the winter months but it was not annually, and it was a real treat to see it. However, since Ivan sightings in the panhandle have become quite common. Folks are seeing them over Pensacola Bay, Perdido Bay, Garcon area of Santa Rosa County, Gulf Breeze peninsula, almost everywhere! I actually saw three flying together over Big Sabine on Pensacola Beach recently. They are actually now nesting in the area.

These are large birds, 30-40” long with a 7-8 feet wing span, and hard to misidentify – everyone knows a bald eagle. However, the juveniles do not have the distinct white head and tail or the brilliant yellow beak. Rather they are dark brown with possible white spots on their wings, and the beak is darker. The mature color change occurs in 5-6 years. Their diet is mostly fish but they will take small birds and mammals. They are also scavengers, including road-kill, and will “pirate” captured food from other birds. Observations support that ospreys and bald eagles do not really get along.

Bald eagles tend to migrate between their breeding grounds in Canada and those of the Gulf Coast. The migrants are typically non-breeding individuals. Breeding ones tend to remain in their breeding areas year round. As of 2014, Florida has the highest densities of southern breeding populations in the lower 48 states, about 1500 nests. Most return to Florida in the fall for nest building. Their nests are typically in forested areas near waterways. They prefer the tallest trees. The nests are quite large; the record in Florida was 9.5 feet in diameter. They typically lay one clutch of 1-3 eggs but may lay a second clutch if the first is unsuccessful. The young remain in the nests until they can fly – usually April or May. Wintertime is a good time to view these animals in our area.

Their numbers plummeted for a variety of reasons, including the introduction of DDT, and they were placed on the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Endangered Species list. DDT was banned in 1972 and listing them on the ESL protected from them from poaching; they have since recovered. Today they are no longer on the Endangered Species list and were removed from the Florida Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commissions (FWC) imperiled species list. However, they are still protected federally by the Bald / Golden Eagle Protection Act and the Migratory Bird Protection Act; they are also protected in Florida by state law.

Potential viewing locations can be found on FWC’s bald eagles nest location site. https://public.myfwc.com/FWRI/EagleNests/nestlocator.aspx

This site provides known locations between 2012 and 2014. Recent surveys were conducted between 2015 and 2016 in several panhandle counties but those locations have not been posted yet. For those in the Pensacola area, there are four permanently injured bald eagles at the Wildlife Sanctuary of Northwest Florida. The public is welcome to visit the sanctuary Wednesday through Saturday from 12:00 – 3:30PM (self-guided).

105 North S Street, Pensacola FL 32505

http://www.pensacolawildlife.com/

For more information:

http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/managed/bald-eagle/information/

http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/profiles/birds/raptors-and-vultures/bald-eagle/

http://myfwc.com/wildlifehabitats/managed/bald-eagle/faqs/

by Carrie Stevenson | Jan 8, 2017

Arbor Day has a 145-year history, started in Nebraska by a nature-loving newspaper editor who recognized the many valuable services trees provide. We humans often form emotional attachments to trees, planting them at the beginning of a marriage, birth of a child, or death of a loved one, and trees have tremendous symbolic value within cultures and religions worldwide. So it only makes sense that trees have their own holiday. The first Arbor Day was such a big success that his idea quickly spread nationwide–particularly with children planting trees on school grounds. In addition to their aesthetic beauty and valuable shade in the hot summers, trees provide countless benefits: wood and paper products, nut and fruit production, wildlife habitat, stormwater uptake, soil stabilization, carbon dioxide intake, and oxygen production. If you’re curious of the actual dollar value of a tree, the handy online calculator at TreeBenefits.com can give you an approximate lifetime value of a tree in your own backyard.

Arbor Day events in the western Panhandle.

While national Arbor Day is held the last Friday in April, Arbor Day in Florida is always the third Friday of January. Due to our geographical location further south than most of the country, our primary planting season is during our relatively mild winters. Trees have the opportunity during cooler months to establish roots without the high demands of the warm growing season in spring and summer.

To commemorate Arbor Day, many local communities will host tree giveaways,plantings, and public ceremonies. In the western Panhandle, the Florida Forest Service, UF/IFAS Extension, and local municipalities have partnered for several events, listed here.

For more information on local Arbor Day events and tree giveaways in your area, contact your local Extension Office or County Forester!

by hollyober | Dec 16, 2016

Christmas trees can provide benefits to wildlife long after they have served as holiday decoration indoors. Credits: IFAS photo database.

Americans purchased approximately 30 million live Christmas trees last year. If you plan to have a live tree this winter, and you’re wondering what you could do with your tree once it has finished its role as holiday decoration in your home, read below. Rather than simply dragging your tree to the curb for the waste disposal truck to pick up, you could prolong the life of your holiday tree by repurposing it to benefit wildlife.

YOUR TREE COULD PROVIDE FOOD FOR WILDLIFE

Many of the needles may have dropped from your Christmas tree as it dried out while indoors, but the branches should still be intact. This means your tree could be used as a frame to present food for wildlife. After removing your indoor decorations, consider propping the tree up in your yard (perhaps using the same stand you used indoors), and adorning the branches with food enjoyed by wildlife visitors. Some low-budget options include mesh bags filled with bird seed (black oil sunflower seed, safflower seed, and thistle (nyjer) are favorites of many common backyard birds), pine cones smeared with peanut butter, home-made suet cakes, and strings of fruit such as apple slices, orange slices, or grapes. If you choose this option, beware that you may attract not only birds, but mammals such as squirrels, raccoons, opossums, and others.

If you’d like to watch your wildlife visitors, be sure to attach the food items with string so that the animals must eat the food at the site of the tree rather than carrying it away to eat or store elsewhere out of view. Consider using a biodegradable string (i.e., cotton) to secure the food items to your tree so you can eventually compost the tree without worrying about needing to remove the string.

YOUR TREE COULD PROVIDE SHELTER FOR WILDLIFE

If you’re tired of seeing your holiday tree in its upright position, consider taking it outdoors, laying it down, and heaping other vegetative debris loosely on top to form a ‘brush pile’. Brush piles are mounds of woody vegetation created specifically to provide shelter for wildlife.

The lower portions of a brush pile can offer cool, shaded conditions that allow small mammals such as rabbits to hide from the weather and from predators. Meanwhile, the upper portions can serve as perch sites for songbirds. The entire pile may be used as resting sites for amphibians and reptiles. In yards with few understory trees or shrubs, and at times of year when many trees and shrubs have limited foliage, these brush piles can provide much-appreciated cover for many kinds of wildlife.

YOUR TREE COULD PROVIDE SHELTER FOR FISH

Your retired Christmas tree could be used to make long-lasting habitat improvements for fish. In artificial ponds with little submerged vegetation, the addition of one or more Christmas trees could upgrade the quality of refuge and feeding areas for fish. Small fishes may hide among purposely submerged Christmas trees for protection, and larger fishes may follow them. If you’ve got an artificial pond on your property, consider adding discarded trees to create a place where fish can hide and find food, and also to concentrate fish for angling. Simply secure a cinder block to your holiday tree using heavy wire or thin cable and place it far enough from shore that water covers the top of the tree by a couple of feet. When constantly submerged, Christmas trees can persist for many years underwater.

Not only can your tree offer enjoyment to you when decorated with lights and ornaments indoors, but it can also allow you to provide post-holiday gifts to the wildlife and fish on your property.

by Sheila Dunning | Dec 5, 2016

Throughout history the evergreen tree has been a symbol of life. “Not only green when summer’s here, but also when

Throughout history the evergreen tree has been a symbol of life. “Not only green when summer’s here, but also when  it’s cold and dreary” as the Christmas carol “O Tannenbaum” says. While supporting the cut Christmas tree industry does create jobs and puts money into local economics, every few years consider adding to the urban forest by purchasing a living tree. Native evergreen trees such as Redcedar make a nice Christmas tree that can be planted following the holidays. The dense growth and attractive foliage make Redcedar a favorite for windbreaks, screens and wildlife cover. The heavy berry production provides a favorite food source for migrating Cedar Waxwing birds. Its high

it’s cold and dreary” as the Christmas carol “O Tannenbaum” says. While supporting the cut Christmas tree industry does create jobs and puts money into local economics, every few years consider adding to the urban forest by purchasing a living tree. Native evergreen trees such as Redcedar make a nice Christmas tree that can be planted following the holidays. The dense growth and attractive foliage make Redcedar a favorite for windbreaks, screens and wildlife cover. The heavy berry production provides a favorite food source for migrating Cedar Waxwing birds. Its high salt-tolerance makes it ideal for coastal locations. Their natural pyramidal-shape creates the traditional Christmas tree form, but can be easily pruned as a street tree. Two species, Juniperus virginiana and Juniperus silicicola are native to Northwest Florida. Many botanists do not separate the two, but as they mature, Juniperus silicicola takes on a softer, more informal look. When planning for using a live Christmas tree there are a few things to consider. The tree needs sunlight, so restrict its inside time to less than a week. Make sure there is a catch basin for water under the tree, but never allow water to remain in the tray and don’t add fertilizer. Locate your tree in the coolest part of the room and away from heating ducts and fireplaces. After Christmas, install the Redcedar in an open, sunny part of the yard. After a few years you will be able to admire the living fence with all the wonderful memories of many years of holiday celebrations. Don’t forget to watch for the Cedar Waxwings.

salt-tolerance makes it ideal for coastal locations. Their natural pyramidal-shape creates the traditional Christmas tree form, but can be easily pruned as a street tree. Two species, Juniperus virginiana and Juniperus silicicola are native to Northwest Florida. Many botanists do not separate the two, but as they mature, Juniperus silicicola takes on a softer, more informal look. When planning for using a live Christmas tree there are a few things to consider. The tree needs sunlight, so restrict its inside time to less than a week. Make sure there is a catch basin for water under the tree, but never allow water to remain in the tray and don’t add fertilizer. Locate your tree in the coolest part of the room and away from heating ducts and fireplaces. After Christmas, install the Redcedar in an open, sunny part of the yard. After a few years you will be able to admire the living fence with all the wonderful memories of many years of holiday celebrations. Don’t forget to watch for the Cedar Waxwings.

by Mark Mauldin | Nov 7, 2016

A buck chases a doe through plots of wildlife forages being evaluated in 2013 at the University of Florida’s North Florida Research and Education Center. Photo Courtesy of Holly Ober

It should be too late in the year for an article about cool season food plots; they should already be up and growing, at the very least planted. It’s November, archery season has begun, the fall food plot ship should have already sailed. However, due to the incredibly dry weather we’ve had for the past several months I hope that ship hasn’t sailed. I hope you have not planted your food plots yet. The tristate area is dry, too dry to plant anything you expect to survive. If you have not already planted, don’t until your area gets substantial rain.

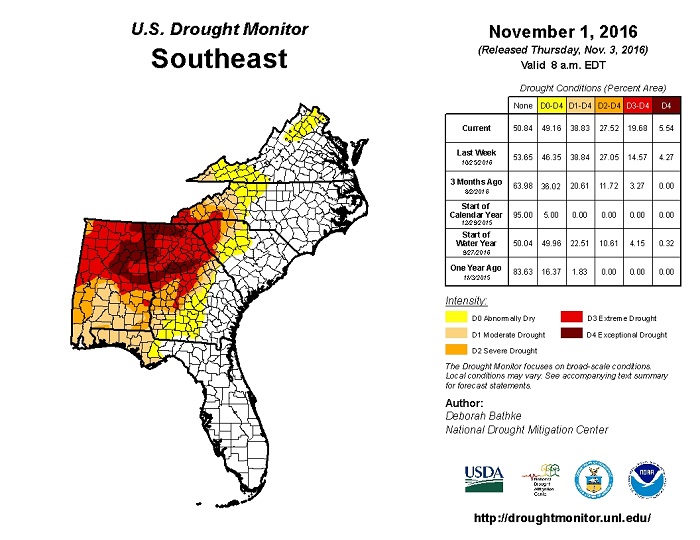

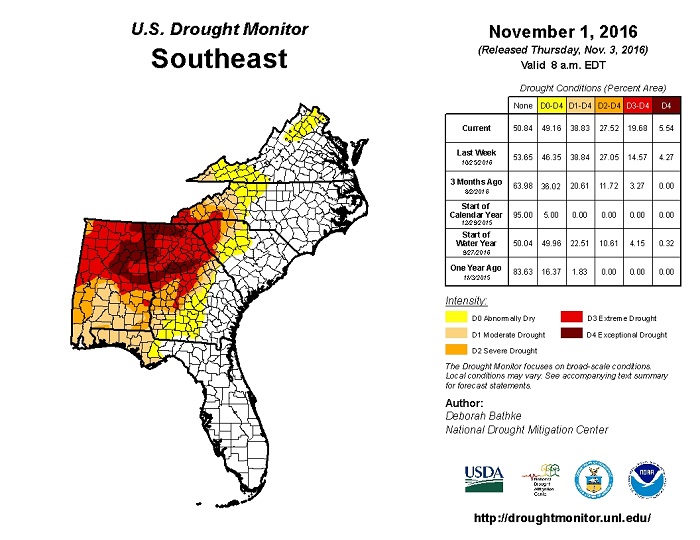

Very dry conditions persist across the Southeast.

The saying goes “The best time to go hunting is whenever I have time”. As the classic weekend-warrior sportsman myself, I can easily relate to that saying and I can also understand how/why folks would apply that same logic to planting food plots. Unfortunately, with this fall’s weather that logic does not hold true. Any plantings made before we have adequate moisture run a very high chance of being complete failures.

These likely failures can playout in a variety of ways but they all end the same. Seedlings have tiny roots systems, moisture must be accessible very near the soil surface in order for them to access it. If moisture is unavailable in the tiny root zone the seedlings will wilt. Wilting greatly diminishes the plants ability to carry out photosynthesis; no photosynthesis no energy. Seedlings have virtually no stored energy to fall back on, so the seedlings begin to die rapidly.

Admittedly, I left out one key detail in the plant horror story above; moisture is required for seed germination. If it is dry enough seeds can be planted and nothing will happen – they won’t germinate, they won’t try to grow, they won’t die from lack of moisture. This fact leads some to conclude, “Plant now and it will come up whenever it rains”. While there is some sound logic in that conclusion, it is a very risky plan when you consider the types of plants we typically include in our wildlife plots. “Dusting in” as it is called in the crop world, can work with larger seeded, deeper planted crops. It is not well suited to small seeded, very shallow planted forages like clover. When a seed is right at the soil surface the tiniest amount of rain or even a heavy dew could provide enough moisture for germination which would likely start the process I described earlier.

The safest bet is to wait until your area has received a good soaking rain and there is a favorable chance for additional rains. As dry as we are now, that first ½ inch shower will not provide adequate moisture for establishment if it is followed by an extended period without additional rain.

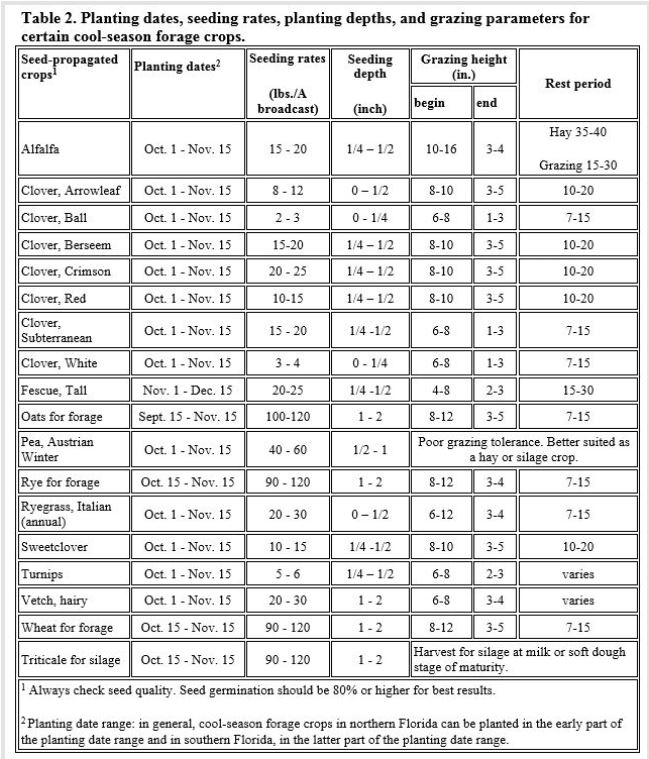

Sooner or later it will rain (I think), so you wind up planting your plots later than normal. What does that mean? In the grand scheme of things, not much. As we get later in the year the days get shorter and the air and soil temperatures get lower which can slow the development of the plants. That said, the real growth for most of our cool season forages really occurs in the spring and that will still be that case regardless of if you planted in October, November or December. Remember the goal of food plots should be increasing the quality and quantity of forage available for wildlife throughout the entire year.

The dry weather has messed up food plot establishment as it relates to hunting season but if all you wanted was a game attractant for hunting purposes food plots were probably not your best bet in the first place. It takes considerable time, effort and expense to maintain quality food plots, to the point that they are really not a very practical option if only viewed as an attractant for a few months out of the year.

If attracting deer, not improving habitat, is your primary goal you might consider establishing a feeding station. Be sure to check FWC regulations before you begin feeding game animals.

Be patient, wait for the weather conditions to improve before planting. There is no point in wasting your time and money on plantings that have a very low chance of being successful. Contact your county’s agriculture or natural resources agent for more details relating to the establishment of wildlife plots.

by hollyober | Oct 22, 2016

Brazilian free-tailed bat (Tadarida brasiliensis) eating a corn earworm moth (Helicoverpa zea).

If you think you’d prefer a world without bats, we present to you three reasons to reconsider. Most negative stereotypes about bats are untrue. The reality is that bats benefit us in numerous ways. Here are a few facts that may convince you we should be thankful for bats rather than fearful of them.

1. INSECTS WOULD BUG YOU MORE IF WE HAD NO BATS

Over two-thirds of the 1,240 species of bats that roam the earth’s skies feed on insects. These aerial acrobats cruise over forests, grasslands, waterways, and crop fields, assisting us by consuming nighttime insects. Bats collect insects using a variety of innovative approaches: some scoop them from the air with their wing or tail membrane and transfer them to their mouths; others nimbly pluck insects off surfaces such as leaves, tree trunks, or even water. These bats are our allies, as they drastically reduce the number of pests that would otherwise bite us or damage our crops. It’s estimated that bats help North American farms save around $23 billion a year. If all bats were lost, the resulting damage to crops due to the insects bats formerly kept in check is estimated to be $74/acre across the US.

2. SOME FOODS AND DRINKS MIGHT BECOME RARE IF WE HAD NO BATS

If you like tropical fruits like mangoes, papayas, guavas, bananas, or figs, you should be thankful for bats. Many bats in the tropics and sub-tropics pollinate and disperse seeds in ecosystems ranging from deserts to rainforests. Bats in the desert visit columnar cacti and agaves, ensuring pollination of the plants responsible for making tequila. Bats in the rainforests help regenerate new forests and ensure availability of many locally-consumed and highly-nutritious fruits.

3. BATS CAN HELP US SOLVE MEDICAL PUZZLES

Bats possess many unique biological adaptations that hold clues vital to solving human health issues. Bats have already made notable contributions to the medical community. The special blood thinning enzymes found in the saliva of vampire bats has helped us understand how to prevent blood clotting during open-heart surgery. The adaptations bats have for seeing in the dark are being studied to see if they could provide insight useful for assisting people who have limited vision.

Despite the many ways bats help us, they remain misunderstood by many. Fear of bats, called chiroptophobia, is the result of negative stereotypes about bats. Most of these stereotypes are downright untrue. First, there’s a common belief that bats get caught in people’s hair. This is highly unlikely: if a bat is agile enough to catch an insect the size of a gnat in flight, it can certainly steer clear of a human head. Second, there’s a common fear that all bats have rabies. In fact, rabies is quite rare among bats, and much more common among raccoons and foxes in Florida. Third, despite the portrayal in movies of bats as aggressive towards humans, bats are in reality not likely to bother people. In fact, they’re generally far more afraid of you than you are of them.

If you’d like to help bats (and perhaps get some free control of insect pests in your area), consider building or buying a bat house for your property. Also consider leaving dead and dying trees in your yard if they’re not a safety hazard, avoid trimming dead fronds off your palm trees, and retain Spanish moss. All of these locations (tree cavities, dead palm fronds, and Spanish moss) offer roosting habitat for bats. By promoting bat habitat, you may boost local bats and find you have fewer insect pests nearby.