by Thomas Derbes II | Aug 23, 2024

Oysters are not only powerful filterers, they also provide a home and habitat for many marine organisms. Most of these organisms will fall off while the oysters are being harvested or cleaned, but some will stay behind and can be found inside or outside of your oyster on the half shell. Seeing some of these creatures might give you the “heebie jeebies” about eating the oyster, they are perfectly safe and can either be removed or, in some cases, consumed for luck. These creatures include mud worms (Polydora websteri), “pea crabs” (Pinnotheres ostreum or Zaops ostreus), and “mud crabs” (Panopeus herbstii, Hexapanopeus angustifrons or Rhithropanopeus harrisii).

Mud Worms (Polydora websteri)

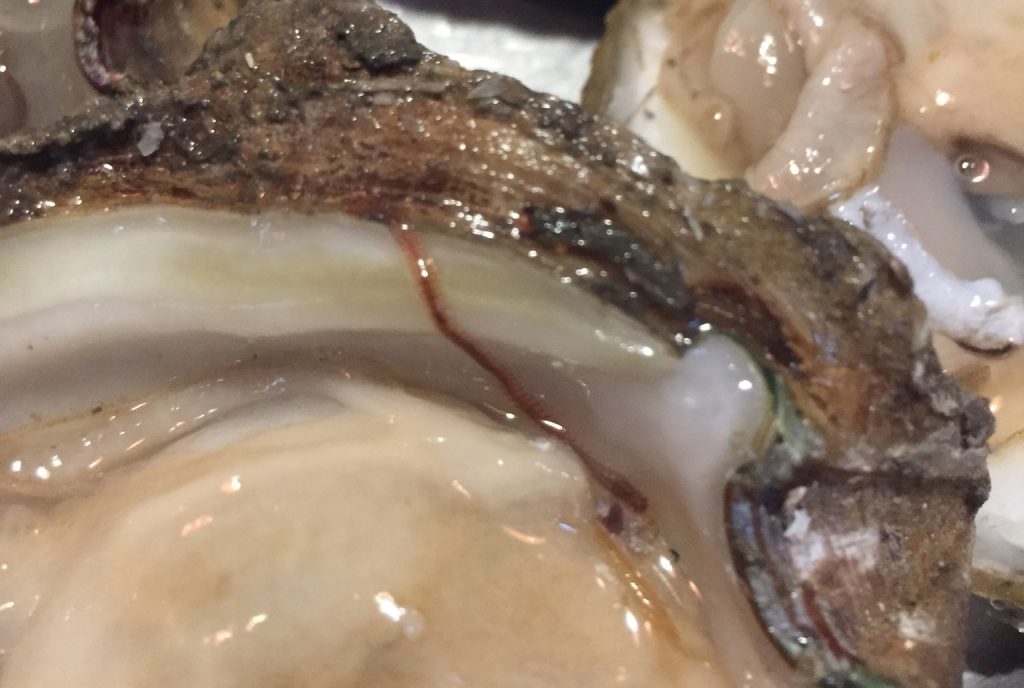

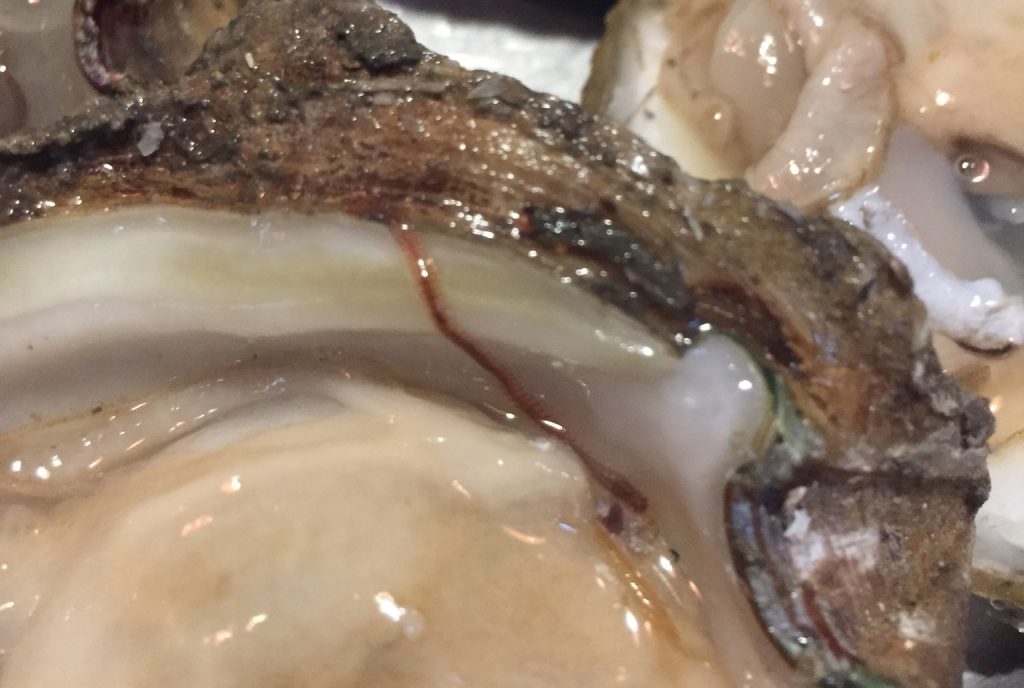

A Mud Worm in an Oyster – Louisiana Sea Grant

One of the more common marine organisms you can find on an oyster is the oyster mud worm. These worms are typically red in color and form a symbiotic relationship with the oyster. Mud worms can be found in both farmed and wild harvest oysters throughout the United States. These worms will typically form a “mud blister” and emerge when the oyster has been harvested. Even though the worms look menacing and unsightly, they are a sign of a fresh harvest and a good environment. Mud worms do not pose any threat to humans and can be consumed.

If you find a mud worm on your next oyster and are still unsure, just simply remove the worm and dispose of it. Dr. John Supan, retired professor and past director of Louisiana Sea Grant’s Oyster Research Laboratory on Grand Isle, mentioned in an article that oyster mud worms “are absolutely harmless and naturally occurring,” and “if a consumer is offended by it while eating raw oysters, just wipe it off and ask your waiter/waitress for another napkin. Better yet, if there are children at the table, ask for a clear glass of water to drop the worm in. They are beautiful swimmers and can be quite entertaining.”

“Pea Crabs” (Pinnotheres ostreum or Zaops ostreus)

“Pea Crabs” are in fact two different species of crabs lumped together under one name. Pea crabs include the actual pea crab (Pinnotheres ostreum) and the oyster crab (Zaops ostreus). These crabs are so closely associated with oysters that their species name contains some form of the Latin word “ostreum” meaning oyster! Pea crabs are known as kleptoparasites and will embed themselves into the gills of an oyster and steal food from the host oyster. Even though they steal food, they seem to pose no threat to the oyster and are a sign of a healthy marine ecosystem.

A Cute Little Pea Crab – (C)2013 T. Michael Williams

Pea crabs are soft-bodied and round, giving them the pea name. Pea crabs can be found throughout the Atlantic coast, but are more concentrated in coastal areas from Georgia to Virginia. While they might look like an alien from another planet, they are considered a delicacy and are typically consumed along with the oyster. If you are brave enough to slurp down a pea crab, you might just be rewarded with a little luck. According to White Stone Oysters, “historians and foodies alike agree that finding a pea crab isn’t just a small treat, it’s also a sign of good luck!”

“Mud Crabs” (Panopeus herbstii, Hexapanopeus angustifrons or Rhithropanopeus harrisii)

Smooth Mud Crab – Florida Shellfish Lab

Just like pea crabs, “mud crabs” is another name for two different species of crabs commonly found in oysters. These crabs, the Harris Mud Crab (Rhithropanopeus harrisii), Smooth Mud Crab (Hexapanopeus angustifrons), and the Atlantic mud crab (Panopeus herbstii) to name just a few, reach a maximum size of 2 to 8 centimeters and are hard-bodied, unlike the pea crabs. Mud crabs can survive a wide range of salinities, but need cover to survive as these crabs are common prey for most of the oyster habitat dwellers, such as catfish (Ariopsis felis), redfish (Sciaenops ocellatus), and sheepshead (Archosargus probatocephalus). These crabs are not beneficial to an oyster environment as they will seek out young oysters and consume them by breaking the shell with their strong claws. If you find a mud crab in your oyster, this is one to dispose of before consuming. However, these crabs typically live on the outside of an oyster and are typically only found when you buy a sack of oysters and do not have an effect on the quality of the oyster.

Don’t Be Afraid

Hopefully this article has helped shed some light on the creatures you might experience when shucking or consuming oysters. Here is a helpful online tool to help identify some marine organisms associated with clam and oyster farms (Click Here). While most of the organisms can be consumed, we recommend the mud crabs be disposed of due to their hard shells. Remember, some of these organisms can bring you luck and with college football season around the corner, some of us might need all the luck we can get! Bring on the pea crabs!

References Hyperlinked Above

by Mark Mauldin | Aug 2, 2024

All graphics and information included are courtesy of myfwc.com.

Here in the Panhandle (FWC Zone D), we are just under 3 months away from the October 26 opening day of archery season. As we move through summer and into the home stretch of hunting season preparations it is important to be sure all hunters understand the current regulations related to deer hunting in our area – it’s more complicated than it used to be.

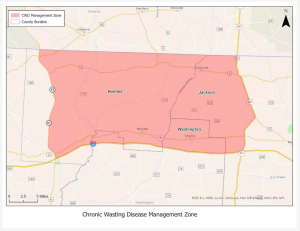

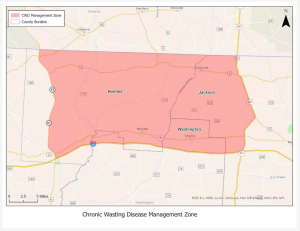

Deer Management Unit map.

From: https://myfwc.com/hunting/season-dates/dmu-d/ Click on image to make larger.

Following last summer’s discovery of Chronic Wasting Disease in Holmes County, the Chronic Wasting Disease Management Zone and its modified regulations will remain in place for the 2024-25 hunting season, but with some notable changes. The entirety of the Chronic Wasting Disease Management Zone lies within Deer Management Unit (DMU) D2. DMU-D2 is the portion of Zone D which lies north of I-10. As such, there are now some considerable differences in the hunting regulations north and south of I-10. For those of us who live along the I-10 corridor and who have opportunities to hunt on both sides of the interstate this could prove a bit confusing. The following is a discussion of the new regulations and how they differ by DMU.

New for the 2024-25 Hunting Season

The feeding of deer within the CWD Management Zone shall be allowed only during the deer hunting season (October 26, 2024 – March 2, 2025). This regulation is specific to the CWD Management Zone, not all of DMU-D2. Anywhere in Florida outside of the CWD Management Zone feeding stations must be continuously maintained with feed for at least 6 months before they are hunted over. So, unless you are hunting inside the CWD Management Zone, I hope your feeders have already been up and running for quite a while.

Chronic Wasting Disease Management Zone From: https://myfwc.com/research/wildlife/health/white-tail-deer/cwd/ Click on image to make larger.

The take of antlerless deer shall be allowed during the entire deer season in Deer Management Unit D2 on lands outside of the WMA system. For all of DMU-D2 there are no “doe days”. If it is hunting season (October 26, 2024 – March 2, 2025), it is legal to harvest antlerless deer in DMU-D2. This is quite different south of I-10, in DMU-D1, where antlerless deer may only be harvested during archery /crossbow season (Oct. 26 – Nov. 27), youth deer hunt weekend* (Dec. 7–8), and specific dates during general gun season (Nov. 30 – Dec. 1, Dec. 28–29).

Up to three antlerless deer, as part of the statewide annual bag limit of five, may be taken in DMU D2 on lands outside of the WMA system. Outside of DMU-D2, there can be no more than 2 antlerless deer included in the annual bag limit of five deer. Event if you hunt outside of DMU-D2 you still have the opportunity to harvest 3 antlerless deer in the 2024-25 season, but at least one of them must be harvested in DMU-D2. The bag limit of 5 total deer remains in place for all DMUs.

All CWD management related regulations can be found here.

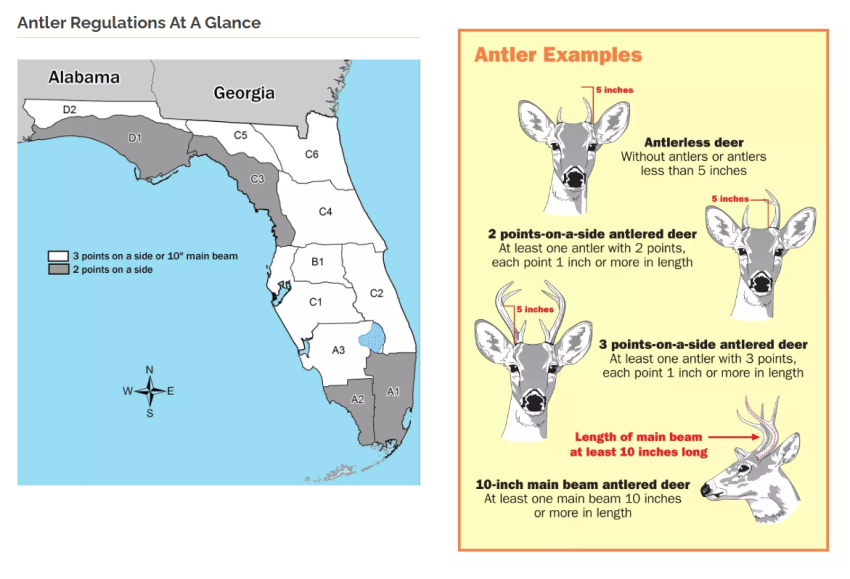

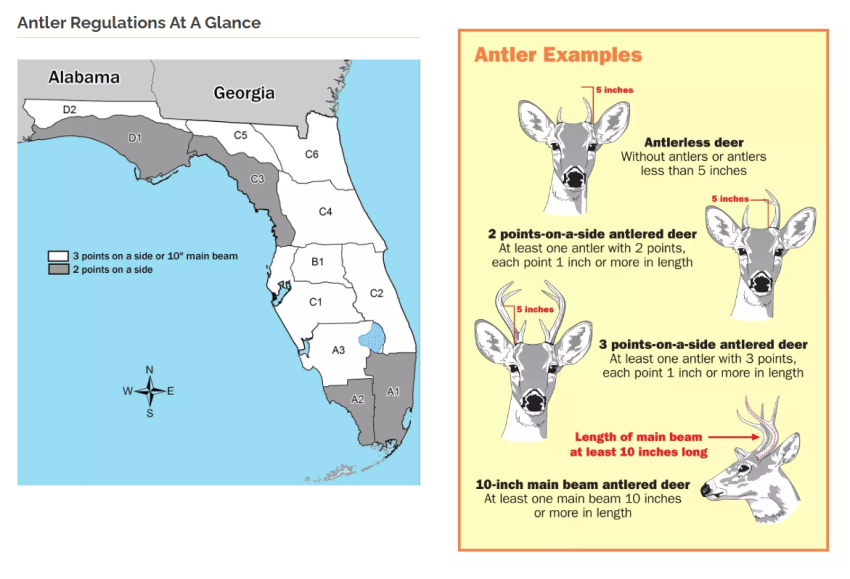

Antler Regulations

While it is not new this hunting season, it should be noted that there are different antler regulations north and south of I-10.

DMU-D1 (south of the intestate) – To be legal to take, all antlered deer (deer with at least one antler 5 inches or longer) must have an antler with at least 2 points with each point measuring one inch or more. Hunters 16 years of age and older may not take during any season or by any method an antlered deer not meeting this criteria.

DMU-D2 (north of the interstate) – To be legal to take, all antlered deer (deer with at least one antler 5 inches or longer) must have an antler with 1) at least 3 points with each point measuring one inch or more OR 2) a main beam length of 10 inches or more. Hunters 16 years of age and older may not take during any season or by any method an antlered deer not meeting this criteria.

In both DMU-D1 & D2 as part of their annual statewide antlered deer bag limit, youth 15-years-old and younger may harvest 1 deer annually not meeting antler criteria but having at least 1 antler 5 inches or more in length.

Florida Antler Regulations

From: https://myfwc.com/hunting/season-dates/dmu-d/

Harvest Reporting

Another somewhat new concept that some hunters still might not be accustomed to is Logging and Reporting Harvested Deer and Turkeys. All hunters must (Step 1) log their harvested deer and wild turkey prior to moving it from the point where the hunter located the harvested animal, and (Step 2) report their harvested deer and wild turkey within 24 hours.**

**Hunters must report harvested deer and wild turkey: 1) within 24 hours of harvest, or 2) prior to final processing, or 3) prior to the deer or wild turkey or any parts thereof being transferred to a meat processor or taxidermist, or 4) prior to the deer or wild turkey leaving the state, whichever occurs first.

Hunters have the following user-friendly options for logging and reporting their harvested deer and wild turkey:

Option A – Log and Report (Steps 1 and 2) on a mobile device with the FWC Fish|Hunt Florida App or at GoOutdoorsFlorida.com prior to moving the deer or wild turkey.

Option B – Log (Step 1) on a paper harvest log prior to moving the deer or wild turkey and then report (Step 2) at GoOutdoorsFlorida.com or Fish|Hunt Florida App or calling 888-HUNT-FLORIDA (888-486-8356) within 24 hours.

by Rick O'Connor | Jul 26, 2024

People enjoy animals. Zoos and wildlife parks are popular tourist destinations and animal programs are popular on television. It is usually the larger predator animals that get our attention. Sharks, panthers, and bears are popular. People like turtles, raptors, and snakes. Other animals are popular as well like antelope, elephants, and deer.

The green sea turtle.

Photo: Mike Sandler

At public aquariums you see exhibits with whales, sharks, and sea turtles. You also see tanks with reef fish, crabs, and octopus drawing crowds. But one group of animals that has never really drawn attention – either at public parks or wildlife television shows – are worms.

Worms are a world of the creepy and gross. To us, their presence suggests dirtiness or environmental problems. But worms are abundant in our environment and play an important role in ecology. In this series we will meet some of them and learn more about their lives. We begin with the flatworms.

As the name suggests, flatworms have flat bodies. In many species their heads can be identified by the presence of eyespots. Eyespots differ from eyes in that they detect light, but do not provide an actual image. Biologists describe animals as being either positively or negatively phototaxic. Most flatworms are negatively phototaxic, they do not like light. To them, light indicates daytime. A time when the predators can see and attack them. So, when they detect light, they move under rocks, mud, whatever to avoid being detected.

Most flatworms are less than 10mm (0.4 in) in length, though some are 60 cm (24 inches). They possess a mouth on their belly side (ventral) and often it is in the middle of the animal, not at the head end. This mouth leads to a simple stomach, but they lack an anus so solid waste must exit the worm through the mouth – what is called an incomplete digestive system.

This colorful worm is a marine turbellarian.

Photo: University of Alberta

One class of flatworms are the free-swimming turbellarians. Most are carnivorous, feeding on small invertebrates and dead carcasses. Some feed on sessile creatures like oysters and barnacles. And some feed on microscopic plants like diatoms. The carnivorous species wrap their prey with their bodies secreting slime over them. They engulf their prey whole. There are two classes of flatworms that are parasitic: the trematodes (flukes), and the cestodes (tapeworms).

Flatworms lack an internal body cavity (coelom) and thus lack internal organs. Not having lungs and kidneys they must take in need gases, and other materials, and well as expel nitrogenous waste, through their skin. Being flat increases their surface area and the efficiency of doing this. This is why they are flat.

Reproduction in flatworms occurs in different ways. Some will reproduce asexually by simple fission – they split apart producing two worms. Many species reproduce sexually using sperm and egg.

Another class of flatworms are the parasitic trematodes; commonly called flukes. They resemble turbellarians in body shape and design, though the mouth is usually at the head end. Most are only a few centimeters long, but one can reach the length of 7 meters (24 feet)! Their bodies are covered with a skin-like material that protects them from the digestive enzymes of their hosts.

The human liver fluke. One of the trematode flatworms that are parasitic.

Photo: University of Pennsylvania

As with turbellarians, flukes are hermaphroditic but use internal fertilization with other worms to produce young, though self-fertilization can – and does – happen. Their life cycles can include one or several hosts. The primary host, the one the adults reside in, are usually vertebrates, most often fish. The intermediate hosts, the ones the juveniles reside in, are often snails but can be other species.

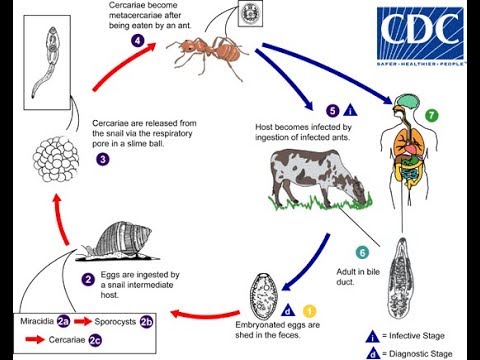

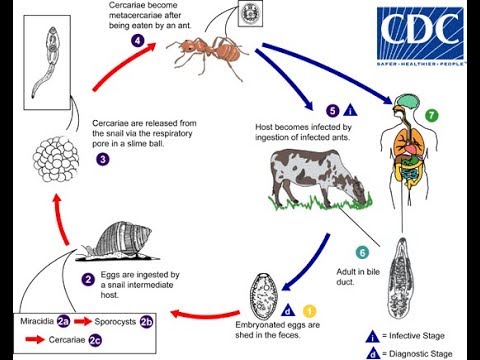

Life cycle of a trematode. Image: Center for Disease Control.

The life cycle is complex, but a general one would include the fertilized eggs being encased in a shell and released into the environment via the feces of the primary host. A ciliated larval stage hatches from this egg and is either consumed by the intermediate host or penetrates the skin of it. Once inside the second larval stage begins. This eventually becomes a third and fourth larval stage. At the fourth larval stage the young worm possesses a mouth and digestive tract. At this stage it leaves the intermediate host as a free-swimming larva seeking a second intermediate host. Here it goes through more larval stages and eventually becomes encased within a cyst (a hard shell). The encysted larva stage enters the primary host (a vertebrate) after that primary host consumes the second intermediate host. Here it develops into the adult trematode.

A third class of flatworms are the parasitic tapeworms – Class Cestoda. Tapeworms differ from other flatworms in that they have a round head – called a scolex – attached to a flat body, and they lack a digestive tract. The flat part of the body is made up of small square segments called proglottids. They continually add proglottids and can become quite long – some have measured over 40 feet! The scolex has four suckers and a ring of small hooks with which they can attach to the inner lining of the digestive tract with.

The famous tapeworm.

Photo: University of Omaha.

The reproductive organs occur within the proglottids. Cross fertilization between these hermaphroditic worms is the rule but self-fertilization does happen. The fertilized eggs are released when the proglottid ruptures and exit the host via the feces.

Tapeworms do require intermediate hosts. The extruded egg hatches into a ciliated larva which is consumed by the intermediate host before that host is consumed by the primary host – typically a vertebrate.

As we can see the lives of these flatworms are (1) secretive, and (2) not pleasant to think about. But they do play a role in our marine and estuarine ecosystem and are very successful at what they do. They should be appreciated for their success.

In our next article on the World of Worms we will look at the nemerteans.

Reference

Barnes, R.D. (1980). Invertebrate Zoology. Saunders Publishing. Philadelphia PA. pp. 1089.

by Carrie Stevenson | Jun 7, 2024

The Chinese wu-ful symbol is a ring of bats used to symbolize luck and blessings in life.

When I start talking about bats, it often elicits a strong response in people. Folks either gush about how great they are, how interesting and helpful, or they shudder and talk about how bats give them the creeps. I understand why they make people nervous. They hide out and swoop around in the dark, may show up in unwanted places (like attics or sheds), and are omnipresent in every creepy horror movie or Halloween theme. Interestingly, the have absolutely the opposite cultural reputation in China. There, bats have been considered a symbol of good luck for millennia. Buildings, jewelry, artwork, etc. are adorned with bats or the “wu-fu” symbol, a circle of five bats. I certainly come down on the side of “bats are the best ever.” Collectively, the bats in our communities eat millions of mosquitoes and agricultural pests every night. Without them, we’d be overrun with insects, disease, and damaged crops.

A wildlife biologist feeds an overwhelmed mother bat and her young after they were found on the ground. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

As a mom, I also have the utmost respect for bat mothers. When a member of this acrobatic species gives birth, it’s done while hanging upside down by her feet. When the baby is born, mom catches it in her wings and the newborn crawls up to her abdomen. Bat babies are not tiny, either—at birth, they are typically up to a third of an adult bat’s weight. Can you imagine giving birth to a 50+ pound baby, while hanging from your feet? Thankfully, most births are single pups, but occasionally multiples are born. Through our local wildlife sanctuary, I once met an exhausted bat mother of triplets. She and her new brood were found together on the ground—mom was unable to carry all three with her as she flew.

Close-up photo of a Seminole bat and her two pups recovering at the Wildlife Sanctuary of Northwest Florida. Photo credit: Carrie Stevenson, UF IFAS Extension

Summer is maternity season for female bats, typically giving birth in May or June. Being fellow mammals, bats must stay near their newborns to nurse. It takes about three weeks for juvenile bats to learn to fly. During that time, they either cling to their mother, nursing on the road, or stay behind in a maternity colony as she feeds at night. For that reason, during the period from April 16-August 14, it is illegal to “exclude” or prevent bats from returning to their roost—even if it’s your attic. Blocking a bat’s re-entry during this time frame could result in helpless newborn bats getting trapped in a building.

So, if you have seen evidence of bats flying in and out of your attic—or another building that should not house them—you will need to wait until August 15 or later. Excluding bats from a building entails waiting for the bats to fly out at night and putting up some sort of barrier to prevent their return. This can be done using several different methods explained in this video or by using a reputable wildlife professional. The Florida Fish & Wildlife Conservation Commission has regulatory oversight for bat-related issues, and they will work with homeowners to arrange a positive outcome for both the homeowner and the animals involved.

On just about any spring or summer night at dusk, you can look up and see bats darting around, chasing and catching insects. If you are a total bat nerd like me, there are also several places around the southeast with large bat houses for public viewing. In Gainesville, the University of Florida bat houses are home to over 450,000 bats that leave the houses every night. An even larger colony in Austin, Texas (750,000-1.5 million bats) flies out at sunset every night to forage from their dwelling under a downtown bridge. Both are fascinating experiences, and worth a visit!

The University of Florida bat houses on the Gainesville campus are home to hundreds of thousands of bats that emerge every evening. Florida Museum photo by Kristen Grace

If you’re interested in building a bat house for your own backyard, reach out (ctsteven@ufl.edu); I have examples at the office and several sets of plans for building bat houses and installing them correctly. The publication, “Effective Bat Houses for Florida” goes through the best way to figure out where to place a house and includes a set of plans.

by Thomas Derbes II | May 3, 2024

I might shock a few people when I say this, but I’d rather be out in the bay somewhere rather than the beach. I just feel like I always bring a gallon of sand back on me even after washing down before getting in the car. However, there is one activity that will always get me out on the beach, and it just so happens to be the right time of the year for it. Florida Pompano (Trachinotus carolinus), aka Pompa-Yes, have started to cruise the white, sandy beaches in search of food as they migrate west to their breeding grounds. While out on a fishing trip this past weekend, the Pompano (and every other fish) eluded me, but I was blessed with an amazing array of wildlife.

When I first arrived at my spot just to the east of Portofino Towers, I was greeted with a pair of Sanderlings (Calidris alba) playing the “water is lava” game while taking breaks between waves to argue with each other and probe the sand with their beaks from marine invertebrates. When I was doing more research on sanderlings, one comment I saw was that they ran like wind-up toys, and that’s the truth! They were pretty brave too, not a single footprint of mine in the wet sand didn’t go un-probed. Sanderlings are “extremely long-distance” migratory birds that breed on the arctic tundra close to the North Pole and winter on most of the sandy beaches in the Gulf of Mexico and around the world. Non-breeding sanderlings will often stay on sandy beaches throughout the summer to save energy. They were great entertainment for the whole fishing trip.

Sanderlings in the Tide Pool – Thomas Derbes II

Brown Pelicans (Pelecanus occidentalis) were out in numbers that day. I am not the best photographer, but I was very proud to capture a Pelican mid-flight. These birds are residents of the Florida Panhandle year-round. If you’ve ever been to Pensacola, you might have bumped into one of the many Pelican Statues around the area, and they’re pretty much the unofficial mascot of the area. I am always amazed at how these seemingly big, clumsy birds can effortlessly glide over the waves and water as if they are the Blue Angels doing a low-pass. Pelicans were almost wiped out by pesticide pollution in the 1960’s, but they have made an incredible comeback.

Brown Pelican – Thomas Derbes II

While I was waiting for a Pompano to bite, I had a visit from a small Atlantic Stingray (Dasyatis sabina) that was caught in the tidepool that was running along the beach. He didn’t seem injured or sick, so I quickly grabbed a glove and released him into the gulf. Stingrays are pretty incredible creatures and can get to massive sizes, but they do contain a large, venomous spine on their tail that poses a threat to beach goers. They are not aggressive however, and a simple remedy to make sure you don’t get hit is to do the “Stingray Shuffle” by shuffling your feet while you move in the water to scare up the stingrays.

Atlantic Stingray Cruising the Tide Pool- Thomas Derbes II

As I was getting ready to pack up, I noticed a new shorebird flying in to investigate the seaweed that had washed up on shore. I had a hard time identifying this bird, but once I was able to see it in flight with its white stripe down the back, I realized it was a Ruddy Turnstone (Arenaria interpres). Turnstones get their name from their foraging behavior of turning over stones and pebbles to find food. Even though we do not have pebbles, the turnstone was looking through the seaweed for any insects or crustaceans that might be an easy meal. Turnstones are also “extremely long-distance” migratory birds breeding in the arctic tundra with non-breeding populations typically staying on sandy beaches during the summer. The turnstone made sure to stay away from me, but I was able to get a good photo of it as it ran from seaweed clump to clump.

Ruddy Turnstone – Thomas Derbes II

While I didn’t catch anything to bring home for dinner, I did get to enjoy the beautiful day and playful wildlife that I wouldn’t have experienced sitting on a couch. You can turn any bad fishing day into an enjoyable day if you pay attention to the wildlife around you!

by Thomas Derbes II | Apr 26, 2024

Imagine you’re out on a kayak in a pristine Florida freshwater spring, surrounded by wildlife, beautiful trees, and natural formations. You have all the knowledge of what to expect and get excited to call out the different species of plants and animals you can spot. You’re surrounded by 10-15 like-minded nature enthusiasts who celebrate every species found and share tips and tricks on how to identify species more efficiently (Watersnakes vs Cottonmouths… Very Important!) If this sounds like a great time, then the Florida Master Naturalist Program might be right for you!

A Great Group of Master Naturalist Students Hiking Around Ponce De Leon Springs- Thomas Derbes II

Since I am a fairly new Extension Agent, I am getting to experience the course from a unique perspective. The Freshwater Course was my first time being an instructor, but it was also my first time going through the course. We started in March and are about to do our graduation next week, but this previous Tuesday was by far the best experience I have had in the course. We started the day at Ponce De Leon Springs State Park with a hike along a tannic creek. Once you reach the end of the trail, you can take the route back that is along the crystal-clear waters that flow from the springs. Largemouth Bass and Bluegill were abundant, and we even spotted a Mountain Laurel Tree. There is a beautiful picnic and viewing area along the springs, and you can even take a dip right in the springs. Even though this isn’t the famed “Fountain of Youth” springs, I think Ponce De Leon himself would’ve had a long soak in these waters.

A Flowering Mountain Laurel (Kalmia latifolia) at Ponce De Leon Springs – Thomas Derbes II

We then took a detour to a Pitcher Plant bog that was along the route to Morrison Springs. After a quick hike, we made it down to a bog that was filled with multiple types of Pitcher Plants, Sundews, and my favorite, Orange Milkwort. We also found a creek and found some slimy friends like a cute tiny frog and an unknown larvae/creepy crawly. We then loaded back up and made the very short trek to Morrison Springs, kayaks in tow.

An Orange Milkwort (Polygala lutea) Near a Pitcher Plant Bog – Thomas Derbes II

When we arrived at Morrison Springs, we had a quick lunch and learn from Dr. Laura Tui about the springs and headed over to the boat launch. We launched our kayaks in the almost crystal-clear waters and set out to find the connection to the Choctawhatchee River. We had our own kayak flotilla, and we were able to talk about all the potential species we would spot. Along our nice, relaxing paddle, we spotted many different birds, turtles, and a Green Watersnake (which I missed out on)! We finished the paddle with a trip around the springs and the vent and slowly loaded up the kayaks to call it a day.

FMNP Instructor Rick O’Connor Leading the Kayak Brigade – Thomas Derbes II

If this sounds like something you want to be apart of, you can check out what Master Naturalist Courses are available in your area by Clicking Here!