by Rick O'Connor | Aug 18, 2021

This is a famous fish. If you look back at the old tourism magazines of the early 20th century you will see a lot about tarpon fishing in Florida. As a matter of fact, some say that tarpon fishing was the beginning of the tourism industry in the state. Also known as “silver kings”, they put up a tremendous fight which anglers love, particularly on lighter tackle. It is a sport fish, not sought for food, so catch and release has been the rule for years. But those who seek them will tell you it is worth the fight even if you must release it.

Tarpon have been a popular fishing target for decades.

Photo: NOAA

Tarpon (Megalops atlantica) are large bodied, large scaled fish, with a deep blue back and silver sides. They are a large fish, reaching over 8 feet in length and up to 350 pounds. They tend to travel in schools and are often associated with other fish, such as snook2.

It has always been thought of as a “south Florida fish”. As mentioned, down there it is a popular fishing target for tourist and residents alike. Many charter captains specialize in catching the fish and they have been featured in fishing programs. But you do not hear about such things in the Florida panhandle. Hoese and Moore1, as well as the Florida Museum of Natural History2 both indicate that they are in fact in the Florida panhandle. As a matter of fact, this fish has few barriers and has the distribution of the classic “Carolina fish” group. That includes the entire eastern seaboard of the United States, the entire Gulf of Mexico, and the Caribbean1. The Florida Museum of Natural History indicates they are found on the opposite shores of the Atlantic Ocean and may have made their way through the Panama Canal to the Pacific shores of the canal. Within this range they are known to enter freshwater rivers. They seem to have few biogeographic barriers.

I grew up in the panhandle and remember hearing about them swimming in our area when I was younger. Fishermen said they would throw all sorts of bait at them. Artificial lures, live bait, cut bait, you name it – they tossed it… the tarpon never would take it. Catching one here was almost impossible. The flats fishing charter trips for tarpon in south Florida would not happen here. I remember once diving in Pensacola Bay near Ft. Pickens. We were looking for an old Volkswagen beetle that had been sunk years ago when at one point the water became very dark – almost like storm clouds had rolled in. When my buddy and I both looked up we saw a school of very large fish swimming above us. We were not sure what they were at first but as we slowly ascended, we realized they were tarpon. It was pretty amazing.

An interesting side note here. In 2020 tarpon were once again seen swimming around the Pensacola area but this time they WERE taking bait. There were several reports of tarpon caught off the Pensacola Fishing Pier and inside the bay. Why change over all this time? I am not sure.

The ladyfish (or skipjack) is the smaller cousin of the tarpon, but puts up a good fight as well.

Photo: University of Southern Mississippi

Tarpon belong to the family Elopidae which also includes another local fish known as the “ladyfish” or “skipjack” (Elops saurus). This is a much smaller fish reaching about 3 feet (and that would be a large ladyfish). The scales of this family member are much smaller, but the fight on hook and line is just as large. The characteristic that places these two fish into the same family (and these are the only two in this family) is the hard bony gular plate found between the right and left side of the lower jaw (in the “throat” area).

Like tarpon, it is not prized as a food fish but more of a game fish. It has the classic wide distribution of the “Carolina fish group” – the eastern seaboard of the United States, the Gulf of Mexico, down to Brazil. Like the tarpon, it is found in brackish conditions but is not mentioned in freshwater. Again, few biogeographic barriers for this fish.

Both members of this family provide anglers young and old with a lot of enjoyment.

1 Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Discover Fishes. Tarpon. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/megalops-atlanticus/.

3 Discover Fishes. Ladyfish. Florida Museum of Natural History. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/species-profiles/elops-saurus/.

by Rick O'Connor | Aug 8, 2021

Like the ancient sturgeon, this is one strange prehistoric looking group of fish. I’ll say group of fish because there is more than one kind. For many, all gars are alligator gars. There is an alligator gar but there are others. Actually, the longnose gar may be seen more often than the alligator gar, but many do not know there is more than one kind.

Gars are freshwater fish, but several species have a high tolerance for saltwater. The alligator gar (Artactosteus spatula) has been reported from the Gulf of Mexico1. They are elongated, slow moving fish with extended snouts full of sharp teeth – very intimidating to look at. But swimming with gars in springs and rivers, I have found them to be oblivious to me. Snag one in a net however, and they will turn quickly and could do serious harm. While fishing my grandson had one come after his bait once and that was pretty exciting, but it is rare to catch them on hook and line. Many who fish for them do so with bow and arrow. Their skin is covered with tough ganoid scales. You really can’t scale them; you have to skin them.

Alligator Gar from the Escambia River.

Photo: North Escambia.com

In the book Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico, by Hoese and Moore, they list four species of gar in the northern Gulf. As the name suggests, the longnose gar (Lepisosteus osseus) has a long slender snout and has spots on the body. It is the one most often seen by people visiting our springs, rivers, and the one most often seen in our estuaries. It can reach a length of five feet3.

The famous alligator gar (Artactosteus spatula) has a shorter snout and spots are usually lacking. If they do have them, the are usually on the fins. This is a big boy – reaching lengths of nine feet and up to 100 pounds2. They are common in coastal estuaries and even the Gulf, though not encountered very often.

The spotted gar (L. oculatus) also has a short snout but has spots all over its body. It prefers the rivers and will enter estuaries only where the salinities are low. It is smaller at four feet4.

Spotted Gar.

Photo: University of Florida

The last panhandle gar is the shortnose gar (L. platostomus). This species too prefers rivers and may enter low salinity bays. It has a short snout and lacks spots.

There is a Florida gar (L. platyrhincus) not found in the panhandle but exists along the central and south Florida gulf coast. It seems to have replaced the spotted gar in this location5.

The biogeography of this group of fish is interesting in that it is an ancient like the sturgeon, it existed during a time period when much of Florida would have been underwater. The general range of gars is the entire eastern United States. They prefer slow moving rivers, or backwaters of faster rivers, and are common in springs. As mentioned, a few species will venture into saltwater and can be found around the Gulf of Mexico. But with several species there has obviously been some speciation over time.

The common longnose gar.

Photo: University of South Florida.

The longnose gars have one of the widest distributions within the group. They are found in most river systems across the eastern United States and all of Florida. It seems to have few barriers including saltwater.

Alligator gars have a similar distribution but seem to be restricted from the peninsula part of Florida. The Florida rivers where they are found are all in the panhandle and are all alluvial rivers – muddy and not tannic like the Suwannee. This could be due to required food that prefer alluvial rivers, pH (pH is lower in the tannic rivers), or something else. Though they did not disperse into central and south Florida, they did extend their range westward down into Mexico. And, as mentioned, have been reported in the open Gulf of Mexico.

Spotted gars follow a similar distribution to the alligator gar. Much of the Mississippi River basin, Florida panhandle, and west to Texas – but they are not found in peninsular Florida. Pre-dating the emergence of peninsular Florida from the sea, there was some barrier that prevented them from dispersing south when the landmass did appear.

A different species appeared in peninsular Florida along with the longnose gar – the Florida gar. It is found in central and south Florida and has dispersed a little north along the Atlantic coast to Georgia.

This is an interesting group of ancient fish. Some are commercially harvested and have suffered from human alterations of river systems. They are amazing to see.

1 Hoese, H.D., R.H. Moore. 1977. Fishes of the Gulf of Mexico; Texas, Louisiana, and Adjacent Waters. Texas A&M Press, College Station TX. Pp. 327.

2 Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. Alligator Gar. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/florida-fishes-gallery/alligator-gar/.

3 Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. Longnose Gar. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/florida-fishes-gallery/longnose-gar/.

4 Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. Spotted Gar. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/florida-fishes-gallery/spotted-gar/.

5 Discover Fishes. Florida Museum of Natural History. Florida Gar. https://www.floridamuseum.ufl.edu/discover-fish/florida-fishes-gallery/florida-gar/.

by Rick O'Connor | Jun 18, 2021

In our continuing series on the biogeographic distribution of island vertebrates, this week we look at a creature that, for some, is as scary as sharks – the rays. The term stingray conjures up stinging barbs and painful encounters, and these have happened, but rays are easily scared away by our activity. Occasionally people will step on one and the venomous spine is used to make you move your foot. You can avoid this by shuffling your feet when moving across the sand. Rays detect the pressure and move before you reach them. Again, negative encounters with rays are not common.

The Atlantic Stingray is one of the common members of the ray group who does possess a venomous spine.

Photo: Florida Museum of Natural History

There are 18 species of rays (from 9 families) found in our area. An interesting note, only eight of those possess a barb for stinging, and five are from the family Dasyatidae (the stingrays). Others that have barbs include the butterfly ray, cownose ray, and the eagle ray.

Rays are related to sharks but differ in that (a) the pectoral fin begins before the gills slits, and (b) the gill slits are on the underneath of the body – not on the side as found in sharks. Shark distribution seems to be controlled by water temperature. We see this with ray distribution as well, but interestingly the skates seem to be restricted to the Gulf of Mexico. Some are found almost exclusively in the east or west side of the Gulf.

Skates resemble stingrays but lack the venomous barb. They will usually have small thorns on their bodies and lay their developing embryos in a leathery egg case folks call “mermaid’s purse” when they wash ashore. There are four species found in the Gulf, but the spreadfin skate is ONLY found in the Gulf of Mexico and is not found along the Florida peninsula. The clearnose skate, which can be found all along Florida and the eastern seaboard of the U.S., is absent from western Gulf. It is interesting to try and understand why. What barrier keeps these two skates from colonizing the entire Gulf?

There is a large plume of muddy freshwater that expands from the Mississippi River into the Gulf off Louisiana. This plume could be a barrier for coastal species trying to expand their range. However, the spreadfin skate is reported to be an outer continental shelf species and may not be influenced by this lower salinity water. So, what is their story?

And why are these not found in the Caribbean? In the Caribbean you do enter tropical waters where coral reefs become more common. There is certainly a species shift when you reach this zone and it could be the food needed by these skates is not found here – a biological barrier. Many find these biogeographic situations interesting.

There are 12 species that have the typical “Carolina marine fish” distribution, which means they are found throughout the Gulf up the eastern seaboard to Massachusetts and south to Brazil. Two, the Atlantic torpedo ray and the roughtail stingray, expand their range farther into Canada. As a matter of fact, the roughtail stingray prefers colder waters.

Torpedo rays are an interesting group. This family of fish includes two species here in the Gulf, the Atlantic torpedo ray and the lesser electric ray. Yep… these two have special muscle cells that can deliver an electric shock. It is believed this electric current can detect and stun prey as well as repel predators. The voltage is not dangerous but will get your attention.

Three of those “Carolina marine species,” the guitarfish, the lesser electric ray, and the yellow stingray, do not reach Massachusetts. Their distribution ends at North Carolina. You would have to guess water temperature as a barrier here. The warm Gulf stream begins heading east across the Atlantic Ocean off Cape Hatteras towards Europe. They could follow this current to Bermuda, but they have not been reported there. This could be due to depth (pressure), being benthic fish, or food barriers.

There is one family that is tropical, the sawfish. These bizarre dinosaur looking creatures were once common in the estuaries of the Gulf region. They are now rare and protected.

One species of stingray, the Atlantic stingray has been found in the lower reaches of Louisiana rivers. Like bull sharks, salinity may not be a barrier for them.

And then we have our “world travelers”. The manta and eagle rays are found across the globe in tropical waters, and eagle rays are common in temperate parts of the world.

The distribution of our rays is not as universal as sharks. The skates in particular have an interesting distribution pattern. Pensacola lies right at the boundary of the eastern and western Gulf of Mexico, so we find both geographic groups here. Though they may scare many people, rays are fascinating creatures and cool to see.

by Rick O'Connor | May 20, 2021

I was recently gathering information together for a presentation on Florida snakes, highlighting those in the Florida panhandle. This particular reference listed 44 species found in the state. Of those, 29 were found throughout the state – north, central, and south Florida. Granted, there were subspecies for many which made for some distinction, but most of our snakes (66%) have few barriers and seem to have adapted to the different habitats and climates. And let’s face it, north and south Florida are two different worlds. That says a lot for the adaptability of these animals, they are pretty amazing.

Snakes do make many nervous but most of our 44 species are nonvenomous.

Photo: Nick Baldwin

Another trend was obvious. As you looked at those species which were only found in north Florida (here defined as the panhandle across to Jacksonville and south to Gainesville) and compared that to species only found south of Gainesville, we have a rich diversity of snakes in our part of the state. There were 12 species found in Florida that were only found in north Florida. South and central Florida only had 3 species that were unique to their part of the state. I saw this same trend with turtles. Of the 25 species of turtles found in Florida, 9 are unique to north Florida, 2 to central and south.

It has been known that the biodiversity of the panhandle is pretty amazing, and that the Apalachicola River basin in particular is a biodiversity hot spot. In the panhandle, several “worlds” collide and species, many using these river systems we find here, can easily reach this area. Some produce hybrid versions of two species. Some produce new species only found here. There may be more reptiles / acre in central and south Florida (I did not look at that) but the variety of these creatures in the north Florida is pretty amazing.

The Escambia River. One of the alluvial rivers of the Florida panhandle. Is a natural highway for many reptiles to disperse into our state.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

But what about those 12 species unique to our part of the state?

Four of them are small terrestrial snakes, rarely getting over a foot in length. These are easy prey and nonvenomous so are most often found beneath the leaf litter of the forest, or beneath the ground, coming out at night to feed on small creatures. We generally find them living in our flower beds and gardens. Most are ovoviviparous (producing an egg but instead of laying it in a nest, the female keeps it internally giving live birth), with only the Southeastern Crowned Snake laying eggs (oviparous).

- Smooth Earth Snake (Virginia valeria) This snake has records from Pensacola Bay area and areas south of the Georgia line.

- Rough Earth Snake (Virginia striatula) This snake has most records west of the Apalachicola River, but there are records from the Suwannee basin in north Florida.

- Red-bellied Snake (Storeia occipitomaculata) Common across north Florida.

- Southeastern Crowned Snake (Tantilla coronate) Found only in the panhandle.

Six of the unique panhandle 12 are nonvenomous water snakes. This would make sense in that we are host to several long alluvial rivers that reach deep into the southeast. The Escambia, Choctawhatchee, and Apalachicola Rivers are highways for all sorts of riverine species, and those closely associated with rivers, to cover hundreds of miles of territory with few barriers (except for the occasional dam). Though these water snakes are nonvenomous, they are known for the “bad attitudes” and high tendency to bite. They feed on a variety of prey and are often seen basking along the riverbank or in a tree branch hanging over the water where they can escape quickly if trouble comes, and they do escape quickly. Some are quite large (over 4 feet) and most are ovoviviparous. The northern watersnake is known to have a placenta-like structure to nourish its young (viviparous) and the rainbow snake lays eggs (oviparous).

The banded watersnake is one found throughout the state and resembles the cottonmouth.

Photo: UF IFAS

- Queen Snake (Regina septemvittata) is only found in the western panhandle (west of the Apalachicola River). This snake likes cold, clear streams with rocky or sandy bottoms and plenty of crayfish.

- Northern Watersnake (Nerodia sipedon) also is only found in the western panhandle. It can be found in almost any body of water and has been reported on barrier islands.

- Plain-bellied Snake (Nerodia erythrogaster) This snake also can be found in just about any water system.

- Diamondback Watersnake (Neroida rhombifer) has only been found in the Pensacola Bay area (Escambia and Santa Rosa counties). They can be found at times in large numbers around almost any body of water.

- Western Green Watersnake (Neroida cyclopion) only as records in one Florida county – Escambia. There they have been found in a variety of water habitats including man-made ones.

- Rainbow Snake (Farancia erytogramma) This snake likes to feed on American eels and is usually found in aquatic systems where this prey inhabits.

Another interesting trend with these unique panhandle watersnakes is the number only found in the western panhandle. Four of the six are only found there and two are only found in the Pensacola area. Some say, “Pensacola is not really Florida”, the snakes might agree.

The last two of the unique 12 are venomous snakes. Florida has six species of venomous snakes, but two are only found in the north Florida.

This copperhead was found JUST across the state line in Alabama. The more copper color and “hour-glass” pattern of their bands lets you know it is not it’s cousin the cottonmouth.

Photo: Molly O’Connor

- Copperhead (Agkistrodon contortrix). Though quite common in Alabama and Georgia, most records in our state are from the Apalachicola River basin area. Many local panhandlers will tell you they see this snake everywhere, but they use this name for the cottonmouth also (a close cousin). The true copperhead is not common here. It seems to like rocky areas further north and is usually found with limestone rock areas that have been formed over time from river erosion.

- Timber Rattlesnake (Crotalus horridus). As with the copperhead, this is a common snake in Alabama and Georgia associated with rocky terrain and is not common in our state. Many ole timers will speak of the “canebrake”, which was found in the common cane of north Florida. There was discussion at one point of this being a separate species from the timber rattler, but the specialist now believe they are one in the same. So, the name canebrake is no longer used by herpetologists. Records of this snake in Florida are mostly east of the Apalachicola River and not common.

This timber rattlesnake has chevrons (stripes) instead of the diamond pattern on its back.

Photo provided by Mickey Quigley

I think the diversity of wildlife in our part of the state is pretty special. Even if you do not like snakes, it is pretty neat that we have so many kinds not found south of the Suwannee River. Snake watching is not as popular as bird watching, for obvious reasons, but it is still neat that we have these guys here.

by Laura Tiu | Mar 26, 2021

I am a curious person by nature. When I first moved to the Emerald Coast, I had many questions about the area. For example, why do they call this the Emerald Coast? To help answer my questions, I turned to the Destin History and Fishing Museum in Destin, FL. If you haven’t yet visited the museum, I highly recommend it for locals and visitors alike.

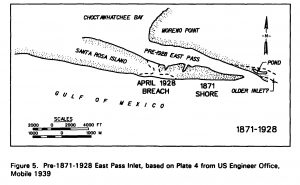

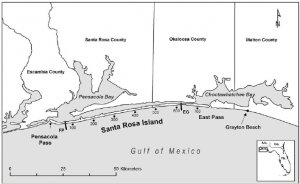

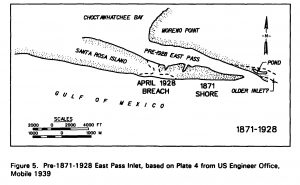

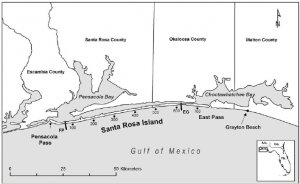

It was easy to see why they call this the Emerald Coast once one lays eyes on the beautiful emerald color water. Other questions weren’t so easily explained. For example, I wanted to know why the pass out of Destin Harbor is called the East Pass, when it is clearly on the west side of Choctawhatchee Bay? In fact, in the early 1900’s, the only outlet from the Bay to the Gulf was about 1.5 miles east of where the current pass resides and was called Old Pass Channel. In 1929, a storm sealed off Old Pass Channel and a heavy dose of spring rain raised Choctawhatchee Bay five feet. The threat of flooding inspired four local fishermen to take matters into their own hands and they dug a small trench across Santa Rosa Island to let the water out of the Bay. By the next morning, the trench had significantly widened into the East Pass we have today, connecting Choctawhatchee Bay to the Gulf of Mexico.

However, that still didn’t explain the East Pass moniker. To explain, we need to look west. Choctawhatchee Bay is connected to Pensacola Bay by the Santa Rosa Sound. This narrow passageway is the space between the Santa Rosa Island, a barrier island, and the mainland. In the early 1900’s, many of the goods and services traded between inhabitants in Okaloosa and Walton counties traveled on ships from Choctawhatchee Bay, through the Santa Rosa Sound, and over to Pensacola Bay, instead of going out into the Gulf. The opening between the Sound and Pensacola Bay is the West Pass, and hence the opening between the Sound and Choctawhatchee Bay is the East Pass. Another mystery solved.

If you are interested in knowing more about the history of this area, the Destin History and Fishing Museum is the place to go.

Citation: Morang, A. . A study of geological and hydraulic processes at East Pass, Destin, FL. Accessed: https://apps.dtic.mil/dtic/tr/fulltext/u2/a253890.pdf

“Foundation for a Gator Nation”