by Rick O'Connor | Jan 17, 2025

So far in this series we have been discussing microscopic creatures in the northern Gulf of Mexico that are single celled – though many may be linked together in chains. In this article we will begin discussing microscopic creatures that are multicellular.

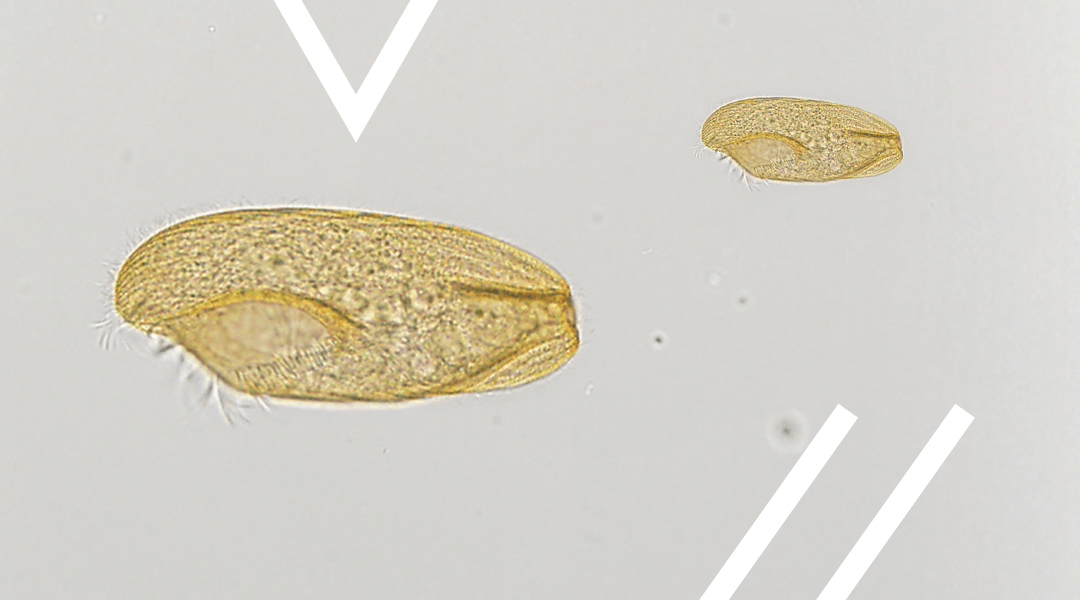

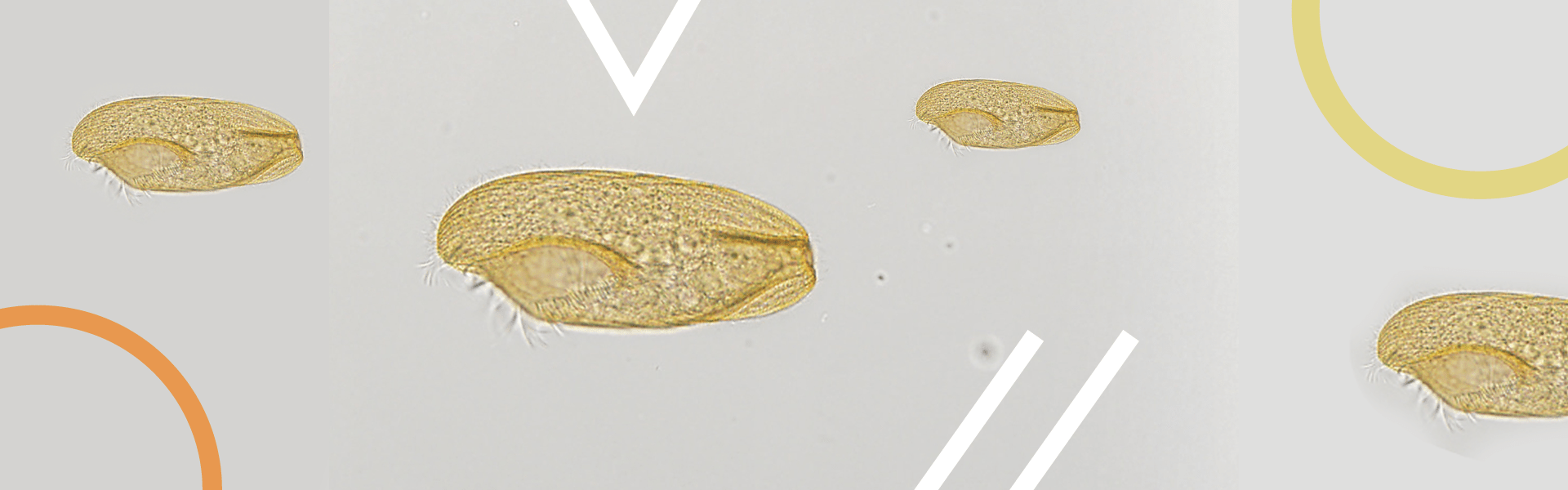

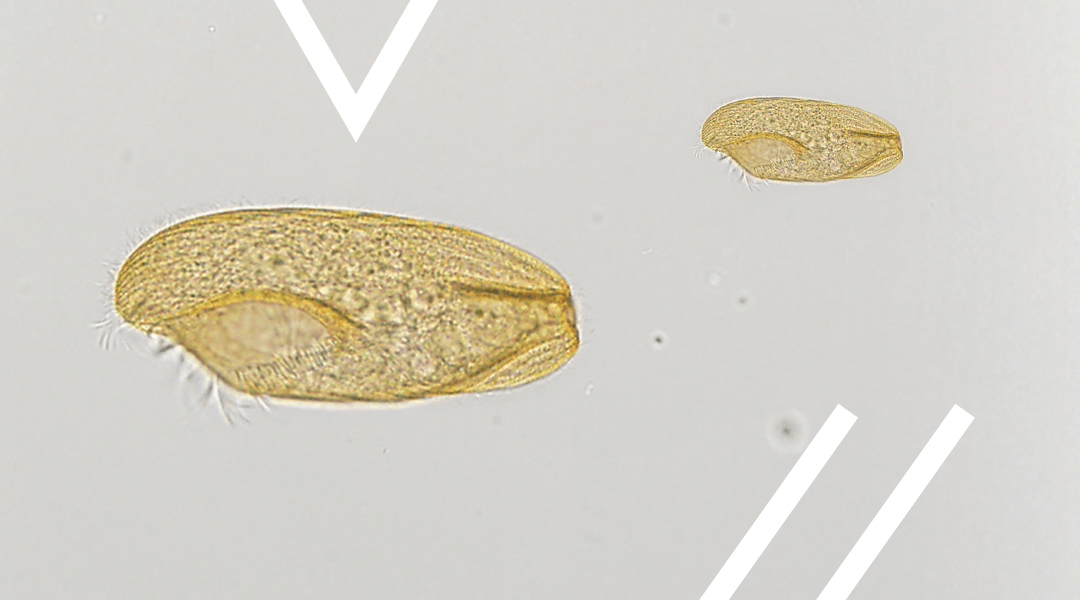

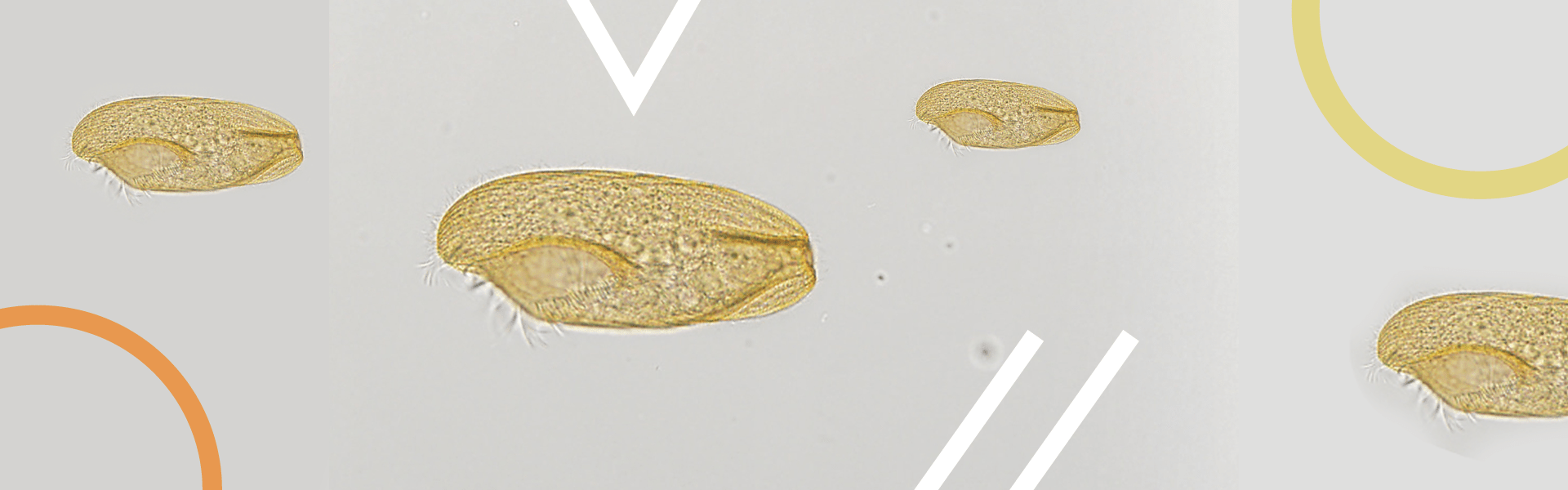

When you do a plankton tow in the northern Gulf, and have a look under the microscope, you will notice most of the moving/swimming plankton are these bug-looking creatures scientists call copepods. The Latin origin of their name (oar-foot) comes from the motion of their swimming legs, which resembles rowing with an oar. They twist and turn all within the field of view, moving quite fast. You will not miss them.

One of the most common creatures in the northern Gulf. The copepod.

Photo: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

It has been stated that the copepods produce some of the largest biomass in the oceans, there are TONS of them within the water column. They swim all through the water column feeding on the phytoplankton we have already discussed in this series. They play a very important role in the food chain connecting the photosynthetic phytoplankton – the “grasses of the sea” – with the consuming animals of the northern Gulf. It has been stated that the copepods are most likely in every creature’s food chain – making them one of the most important members of the northern Gulf of Mexico community. In addition to connecting the marine animals to the primary producers, they also are important at removing carbon from the surface waters of the oceans, reducing the negative impacts of excessive carbon in the atmosphere.

As mentioned, they are multicellular but still microscopic. We also mentioned they look like bugs and are in the Phylum Arthropoda along with the true bugs. Arthropods have jointed legs, antennae, and an exoskeleton that must be shed during growth – and this is the case with the copepods. They are in the Subphylum Crustacea – indicating they are related to shrimps and crabs. Most are between 1-2mm in length but can reach lengths of 10mm and large to be seen in a glass of sea water as flecks darting about. Most have a single compound eye and, along with their antennae, can detect the movements of both predators and prey.

Many larger creatures of the northern Gulf feed on them directly – such as the plankton feeding fish and whales. But most include them as a lower part of their food chain. Copepods can sense the presence of such predators and are quite fast swimmers. They have been clocked at 295 feet in one hour – which is equivalent to a human swimming at 50mph!

Though you will never see them when you visit the beaches, they are one of the most abundant, and ecologically important, creatures in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

References

Copepods. National Museum of Natural History. https://naturalhistory.si.edu/research/invertebrate-zoology/research/copepods.

Copepod. Monterey Bay Aquarium. https://www.montereybayaquarium.org/animals/animals-a-to-z/copepod.

Walter, T.C.; Boxshall, G. (2024). World of Copepods Database. Accessed at https://www.marinespecies.org/copepoda on 2024-11-17. doi:10.14284/356.

by Rick O'Connor | Jan 10, 2025

After two articles on protozoans, we now know what these animal-like creatures are. We have discussed some that move by flagella, and others than move by pseudopodia. The last group by short flagella called cilia.

Ciliates are often covered with these small hair-like structures and can move them relatively fast. Thus, they swim MUCH faster than flagellates, and both are faster than the amoeboid sarcodinids.

They are easy, and not easy, to identify under a microscope. You will be examining the slide seeing diatoms and dinoflagellates scattered across the screen, an occasional flagellate slowly swim by, the very slow fried egg-looking amoeboid slime through, and then a dot/cell will zip by at high speed. That was a ciliate. Easy to identify because anything moving that fast is a ciliate. Hard to identify because you have NO idea which one. Under the heat of the light, they will eventually slow down, and you can better see them for identification.

Ciliated cell found in soil.

Photo: Florida Atlantic University

Most ciliates have an open mouth and what is called an oral groove. This groove acts like a throat leading the food to the food vacuole – where it is digested. Waste will live the protozoan either through the cell membrane, or back out the mouth. At the opening if the mouth are numerous cilia that generate a current sucking up food like a vacuum cleaner and moving it down the oral groove. Most have many nuclei which are easily seen under the scope. They move through the water column collecting food and moving it down the food chain. Most lack shells, so do not contribute to the sediments of the ocean floor or on our beaches.

Up to this point in the series we have been discussing the microscopic phytoplankton and zooplankton found in the Gulf of Mexico. These are creatures few know about, nor do they understand their importance in cycling food, energy, nutrients, and other chemical processes that keep the ecology of the northern Gulf of Mexico in balance. But is now time to turn our attention to the larger – macroscopic – creatures of this world. We begin with seaweed.

References

Yaeger, R.G. 1996. Protozoa: Structure, Classification, Growth, and Development. Chapter 77. Medical Microbiology, 4th edition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8325/#A4082.

by Rick O'Connor | Dec 20, 2024

In our last article we asked the question – “what are protozoans?” As we mentioned then the breakdown of the word includes “proto” which means “before”, and “zoan” which refers to animals. These are the “before animals” – meaning animal-like creatures BEFORE there were true animals.

They are single celled creatures that lack a cell wall and chlorophyll – animal-like – but they are only single celled – so, not true animals. Being animal-like means they cannot produce their own food as the diatoms, dinoflagellates, seaweeds, and true plants do. Rather, they must consume food as animals do. Some feed on diatoms and dinoflagellates. Some feed on decaying organic matter on the seafloor. Some are parasitic and feed off of a host organism. Some feed on other protozoans. And some do a combination. But they are all consumers.

The group is classified into six phyla mostly based on how they move. One subphylum is the Sarcodinids – which move using blobby extensions of their cytoplasm called pseudopods. Under a microscope they would resemble a fried egg oozing across the slide. They are NOT fast. They can use these pseudopods not only for moving but for gathering food. I remember watching them under a scope in college. They slowly oozed across the slide engulfing most other protozoans and phytoplankton they encountered. They were like the “sharks” of the micro-world. Many live on the seafloor, or within the sediments themselves. Some are parasites. And there are a few planktonic forms. Their primary role in the marine system is moving energy through the food chain and cleaning up the environment. As with the flagellates, there two common groups in marine waters – the foraminiferans and the radiolarians.

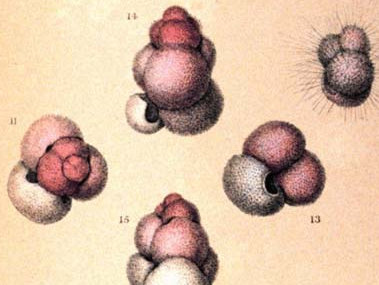

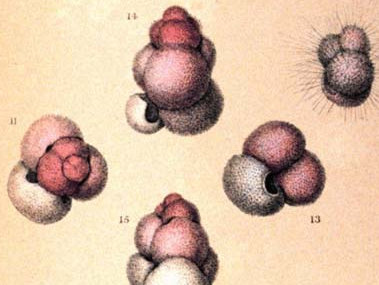

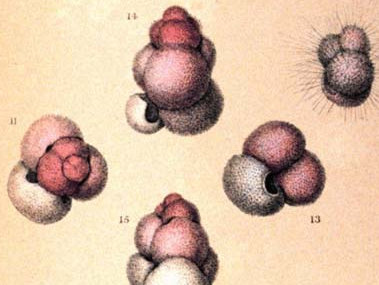

The first true oceanographic research cruise was the voyage of the HMS Challenger in 1872. The chief scientist on this first expedition was Charles Wyville Thomson, a marine geologist and one very interested in what was on the ocean floor. During the first leg of the voyage – from Europe to the America’s – they collected sediment samples several time each day. By far most of the ocean floor was made of what was called “globigerina ooze”. Globigerinids are a group of marine foraminiferans. They produce a calcium carbonate shell that is chambered. Under a microscope they look very much like seashells. They are part of the plankton layers in the ocean – what would be called “zooplankton”. Many possess spines on their shells to help reduce sinking. When they die their shells fall to the seafloor. Over time they formed the thick layers of sediment Thomson witnessed and called “ooze”. He also discovered that most of the ocean floor is covered with these microscopic shells. The Gulf of Mexico is no different. Most formaminiferans live on the seafloor and contribute to the sediment layers from there. One group forms mats on rocks that look pink in color and are responsible for the pink sands found in Bermuda.

Artist image of Globigerina.

Image: NOAA

Another group of shelled amoeboid protozoans are the radiolarians. Under the microscope these are some of the most beautiful creatures you will find in the northern Gulf. Like diatoms, their shells are made of silica and look like glass. Most have spines and shapes that make them resemble snowflakes – truly beautiful. Like foraminiferans, when they die their shells settle on the seafloor and contribute to the ooze layers. Radiolarian ooze has been found as deep as 12,000 feet.

The snowflake-like shells of radiolarians.

Image: Wikipedia.

These small, microscopic amoeba like animals play an important role in moving food and energy through the Gulf. Their discovery on the seafloor helped marine geologists better understand how our oceans formed and how they have changed over time. On other beaches around the world, they have contributed to sands giving some beaches very unique colors – which are popular with tourists. They are an unknown, but important part of the marine community in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

References

Yaeger, R.G. 1996. Protozoa: Structure, Classification, Growth, and Development. Chapter 77. Medical Microbiology, 4th edition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8325/#A4082.

by Rick O'Connor | Nov 22, 2024

You may ask – “what are protozoans?” It’s a good question. The breakdown of the word includes “proto” which means “before”, and “zoan” which refers to animals. These are the “before animals” – meaning animal-like creatures BEFORE there were true animals.

They are single celled creatures that lack a cell wall and chlorophyll – animal-like – but they are only single celled – so, not true animals. Being animal-like means they cannot produce their own food as the diatoms, dinoflagellates, seaweeds, and true plants do. Rather, they must consume food as animals do. Some feed on diatoms and dinoflagellates. Some feed on decaying organic matter from the seafloor. Some are parasitic and feed off a host organism. Some feed on other protozoans. And some do a combination. But they are all consumers.

The group is classified into six phyla mostly based on how they move. One subphylum is the Mastiogophorans – which move using flagella. Flagella are long whip-like tails that extend from the cell and can “twirled” in a fashion that will help the cell move around in the environment. Flagellates can have one or many flagella. Most are not free-swimming in the water column but live on the bottom or are parasitic. Two groups common in marine waters are the choanoflagellates and the coccolithophores.

Choanoflagellates are cells that usually possess one flagella that is protected by a funnel shaped structure called a collar. They are often called “collar cells”. Though found in many benthic environments they are most famous for their role in sponges. Here they live within the walls of the sponge, twirling their flagella to generate a current that draws water into the sponge for feeding. The currents generated by the choanoflagellates also move waste and reproductive gametes out of the sponge into the environment.

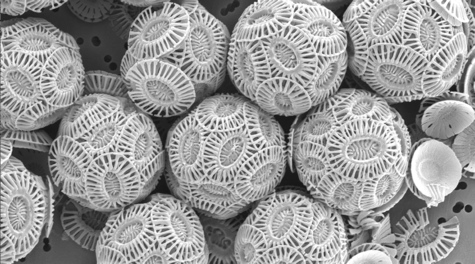

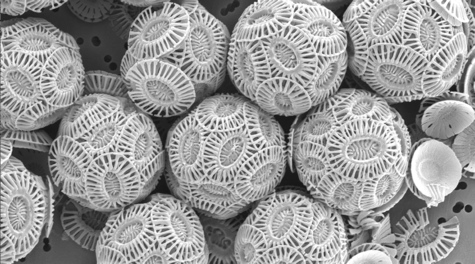

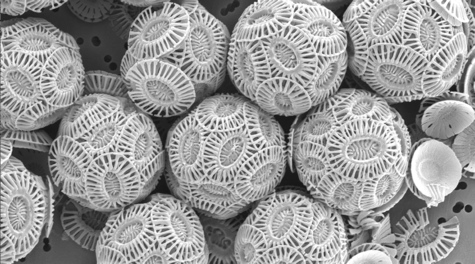

Coccolithophores are flagellated protozoans covered by calcium carbonate plates. These are more common in the plankton of the Gulf of Mexico and play an important role in the carbon cycle. They convert CO2 into calcium carbonate, and other forms of carbon, reducing the CO2 levels in both the atmosphere and ocean, that plays a role in ocean acidification.

Coccolithophores are flagellated creatures covered in calcium carbonate plates.

Image: National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

An interesting note here… when I was in college, we studied the dinoflagellates in both marine botany AND marine invertebrate zoology. I was quite confused… are they “plant-like” or “animal-like”? They could not be both… When I asked my marine botany professor she was adamant, they were part of the “plant world”. But my marine invertebrate zoology professor felt the same – they were definitely in the animal world. They both mentioned this was why they were listed in their own phylum and agreed to disagree. Dinoflagellates (which we have already covered in this series) do photosynthesize, and they do consume other plankton. The same is true for coccolithophores. A quick look on the internet they were described as “phytoplankton” not “zooplankton”. I am including them here – and know they are called coccolithophores. I also know they are one of the creatures found in the northern Gulf of Mexico.

References

Yaeger, R.G. 1996. Protozoa: Structure, Classification, Growth, and Development. Chapter 77. Medical Microbiology, 4th edition. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK8325/#A4082.

by Erik Lovestrand | Nov 22, 2024

In early November a local crabber, Kevin Martina, brought an interesting catch to the Franklin County Extension office in Apalachicola. Kevin and his brother Kenneth Martina fish for blue crabs in Apalachicola Bay and they came across what appeared at first glance to be a red-colored blue crab. In all their combined years of working crab pots, neither of them had seen a crab like this. On closer inspection at the Extension Office, there appeared to be some differences from a blue crab, other than the striking red coloration. It was the innate curiosity of our Extension Office Manager, Michelle Huber, that led us to the discovery that the crab was a species with a native range spanning Jamaica and Belize to Santa Caterina, Brazil. After Michelle showed photos of what she had found on her phone, we reached out to colleagues at the Apalachicola National Estuarine Research Reserve (ANERR) and told them we might have a Bocourt swimming crab (Callinectes bocourti). I told them that I could find no range maps indicating this species lived in our region. The nearest US Geological Survey data points for the species in the Gulf of Mexico were Alabama to the West and the Florida Everglades to the South. It was not long after the ANERR staff reached out to the Fish and Wildlife Conservation Commission that we received interest in confirming the identification and officially documenting the Bocourt swimming crab find.

Bocourt Swimming Crab – USGS/South Carolina DNR

The first documented occurrence of a Bocourt swimming crab in the US happened in 1950 in South Florida. Since then, there have been rare finds in AL and MS and more common occurrences from South Florida all the way up to North Carolina on the Atlantic Coast. Theories about how they arrived include possible transport of larvae in ships’ ballast water or a natural expansion of range with the aid of various ocean currents like the Gulf Stream or by hitching a ride on floating debris from the Caribbean. Ecologically speaking, Bocourt crabs and our native blue crabs have virtually the same dietary habits and both species occur together throughout some parts of their native range. Even though there is likely some competition for food and refuge habitat, it doesn’t appear at this time that one of these crabs would dominate the ecosystem over the other. It also is not evident that Bocourt crabs are reproducing and established in the Northern Gulf of Mexico to-date.

If you are a commercial crabber in the Florida Panhandle, or happen to fish a few recreational traps, we would be interested to know if you have seen this species before. Location data and any good photos of specimens would go a long way to help monitor the species occurrence in our region. You can reach out to me at Elovestrand@ufl.edu or contact your local County Extension office to pass the info my way. Happy crabbing!